I’ve been in a Summerschool last week entitled Social Shaping of Innovation (PDF), organized by the SPIRE center in Southern Denmark University. The event gathered PhD students from many countries working with social aspects in Innovation Management, Design and Engineering.

For me, it was an intense and positive experience. I’ve met a lot of people working with related topic as mine with slightly different perspectives. To be honest, I felt a little bit frustrated at the end because I didn’t felt challenged to rethink my viewpoint on the subject; I felt more like confirming rather than changing. But it was worth. Here follows some insights I got from it.

Social relationships are material

We spend the whole week talking about social relationships in organizations. Most of the people I’ve met were not only interested on to understand these relationships, but on how to change them to promote innovation. We agreed that it was difficult to understand their complexity, even more to intervene on them.

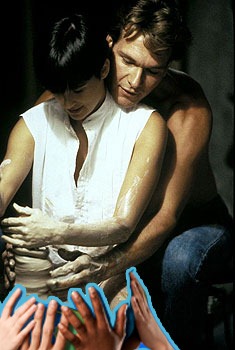

The concept of “social shaping” reminded me of a famous scene from the film Ghost, where Patrick Swayze and Demi Moore shape together a piece of clay on a torn. A piece of pottery is getting shaped by the touch of their joint hands, but at the same time their relationships is being shaped by the pottery, creating an outstanding romantic context. It seems to me that “social shaping” is like letting a lot of hands to touch the clay.

During the Summerschool, little was mentioned about technology, which was taken as one possible result of social process. But I prefer to think that technology is itself a social process and as so, is shaping relationships as well. As Peter Paul Verbeek explains in his book, things and humans coshape reality. A social relationship can be reified into things, but it’s still a social relationship. Marx and, later, Adorno criticized reification to be an alienating device for capitalism but, if the reification process is done collectively as in a participatory process, can that be considered alienating? That’s one of the questions that I could not find an answer yet…

Nomenclatures defines agency

During the Summerschool people used many different nomenclatures to refer to people in organizational contexts: customer, user, member, guest, participant, subject. This words are by no means equivalent: they define clear expected social roles. A customer is expected to buy the product, a user to use the product, a member to feel part of a group, a guest to be curious, a participant to be active, a subject to be enigmatic.

If one person tries doing something different that was expected, he can fall onto another category or, if there many people that don’t fall in any existing categories, the organization can create new hybrid categories like prosumer, cocreator. These labels also imply new strategies for organizations.

Karen Norman spoke about the generalized other, a concept she got from George Herbert Mead to explain how people see themselves and others according to shared experiences. The generalized other is an imaginary profile of a person that we create to anticipate what strangers could do to us and also how we define ourselves according to common profiles.

It’s clear to me that the generalized other has a profound impact on individual’s agency. We act according to what is expected (or not) from others and vice versa.

The silent conversation

We had many short theater plays from Dacapo actors along the program to serve as a material for discussions. They played typical situations in organizations like the picture below, where Research & Development people are discussing the next big thing for their company to invest on. The guy on red sweater doesn’t say any word when the woman in the middle proposes her idea, but his body language says everything: he’s not interested at all. Of course the two women notice that and try to push him to open his mind until they got to a clear conflict. The play stopped and we had the opportunity to discuss it.

First thing that I noticed was the thicker conversation going on beyond spoken and body language. Each word or gesture was tied to set of expectations, past experiences, anticipations, intentions, tactics that could not be heard nor seen directly. The beauty of actor’s work was precisely on how they embodied all this complexity and acted in a coherent way.

That remembered me of Edward Hall metaphor of culture as an iceberg, where the invisible part accounts for most of what shapes our behavior. Hall emphasized that to understand the invisible aspects, you need to participate in the social activities. We realized this argument when the actors invited the audience to jump into the play. It was an outstanding opportunity to realize how different it is to analyze a situation from distance and to be part of it.

Design F(r)ictions for Social Innovation

What I really liked from the Summerschool was the usage of fictions for organizational change. In a fictional space, people are more willing to work with conflicts, which, for me, is the major source of innovation. Conflicts make people rethink their assumptions and push them to do something. It requires analysis and synthesis, creativity and criticism, think and action at the same time. It’s a dangerous business that destabilize social relationships to provide great innovation or terrible destruction. To prevent destruction, conflicts should not be heated too much. That’s why fictions are useful. You can stop them anytime or disbelieve them when they get too painful.

I’m looking forward to apply the Theater of the Oppressed methodology for generating Design Fictions in this future research project, which could be better named Design Frictions. Design Frictions are dramatic stories about communities challenging the future designed for them. They put current or new technologies in conflictual scenarios, making explicit social problems that technologies can bring. Alternative better scenarios can follow, if it’s possible.

I can give an example. Counter Strike was a very popular game played in Brazilian LAN houses, a place where people that don’t have a computer at home go to play games or have Internet access. The game became very popular after a player created a map called cs_rio in 2001, that featured Rio de Janeiro’s favelas as the game context. Players could chose being a either a drug dealer or a policeman and fight each other until one of the sides win. The game was forbidden in Brazil in 2008, accused of stimulating violent behavior. In response to the prohibition, a player made a fictional video featuring politicians face in the game. His argument was that politicians corruption stimulated much more violence rather than the game itself.

I believe that fiction could be better explored by Participatory Design. It’s a format that affords expressing conflicts, complexity, emotions, sequence in current and future contexts. Funny enough, playing theater, film or games in an organization can provide true social innovation.