Visual dialogue is a hybrid between visual thinking, scribing, and dialogic action. In this process, ideas are expressed through simultaneous verbal and visual communication.

Visual dialogue is a way of thinking and communicating that combines speech and drawing to help make abstract ideas more concrete. Often, when people start a conversation about a complex topic, they begin with broad, intuitive concepts that feel meaningful but are difficult to fully articulate into simple words.

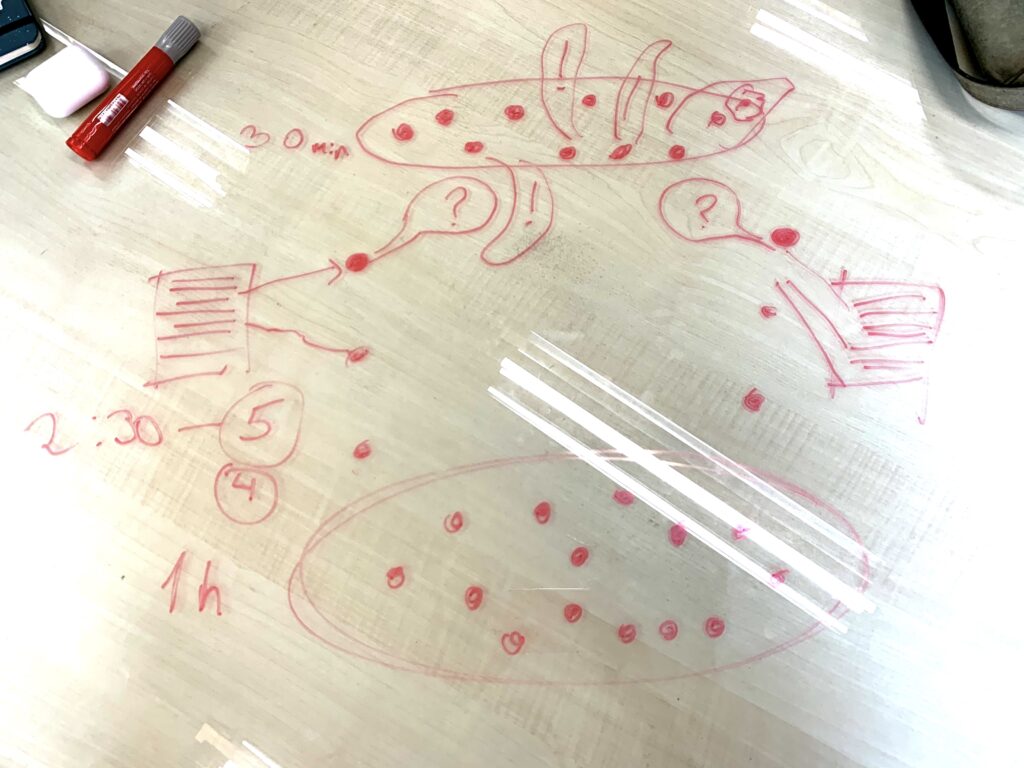

These ideas can be rich and promising, but without a clear structure, they remain vague, floating in an abstract space without a firm connection to reality. This is where visual dialogue plays a crucial role. By sketching while talking, participants externalize their thoughts, making them visible not just to others but also to themselves. This process does more than organize ideas neatly—it reveals their inner potential movement through the dialogue (what they are up to or what is about to happen).

A useful way to think about this process is through the metaphor of matryoshka dolls, the traditional Russian nesting dolls. Just as each doll contains another within it, ideas in a discussion often contain layers of meaning that are not immediately visible. As people engage in visual dialogue, they begin to open up these layers, revealing the underlying structures and tensions that shape their thinking.

Instead of simply adding details to an existing idea, visual dialogue helps uncover the forces that shape it, revealing its tensions, contradictions, and potential for change. The most meaningful concepts often appear where different ideas intersect, where a contradiction forces a shift in perspective, or where someone makes a surprising connection that changes the direction of the discussion.

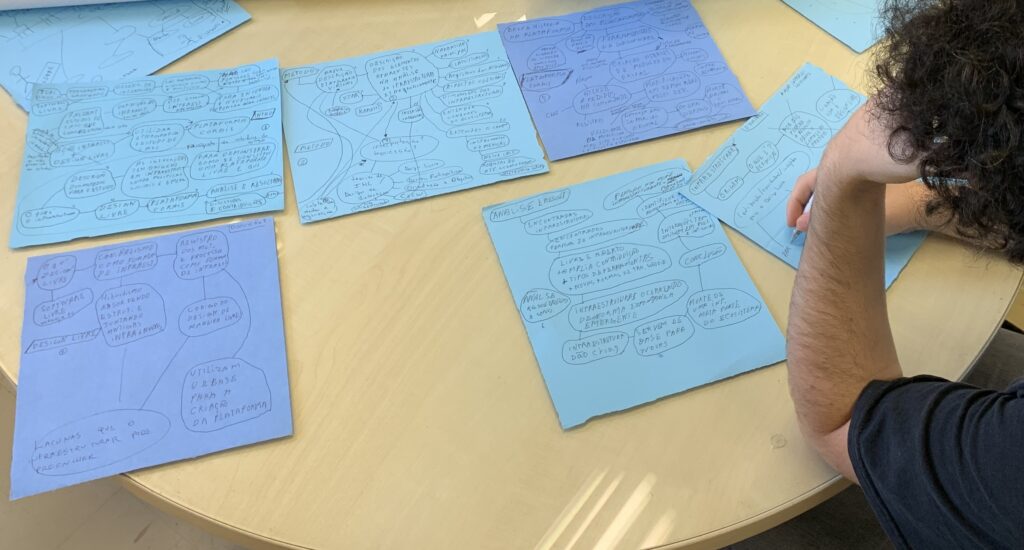

However, this process is not simply about breaking an idea down into smaller pieces. Instead, it is about recognizing how different levels of thought interact, influence one another, and sometimes clash. Each sketch, diagram, or mark on the whiteboard adds a new layer to the conversation, making it possible to see both the big picture and the fine details at the same time.

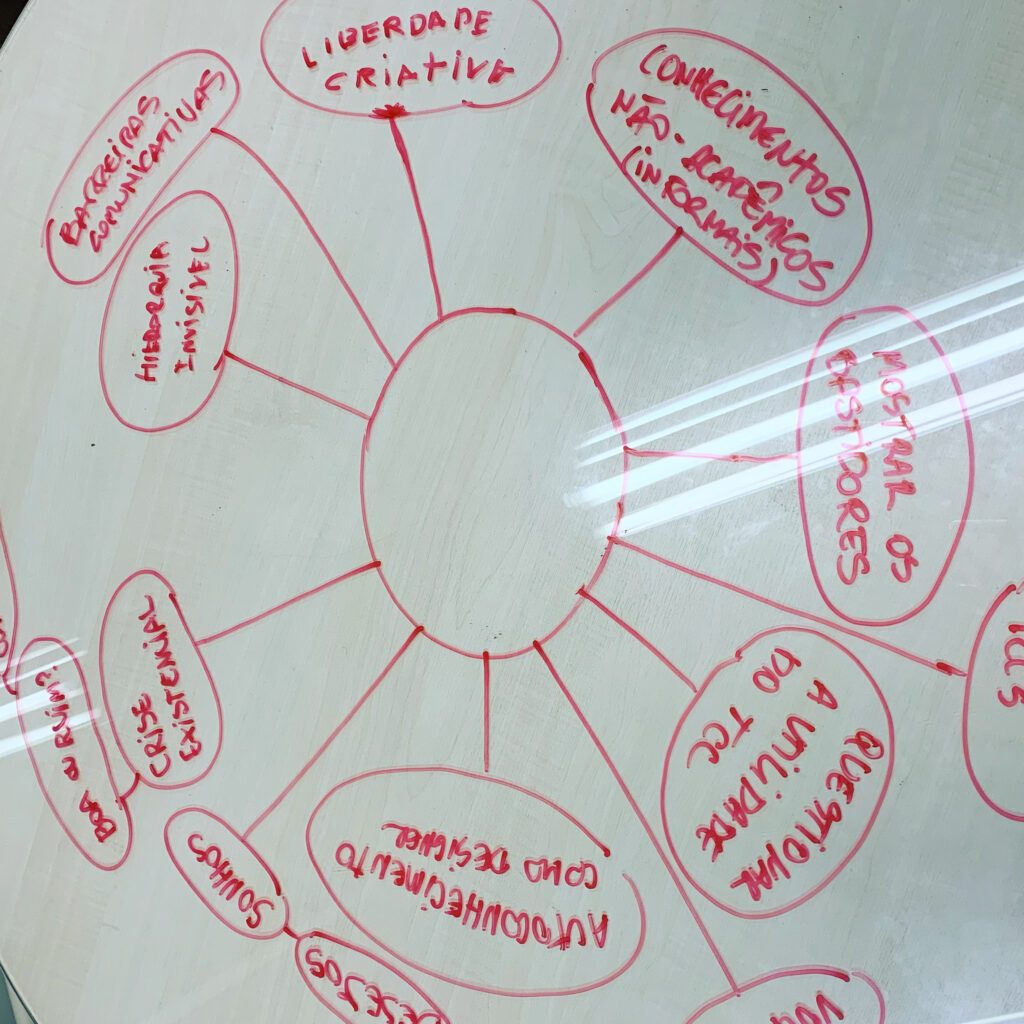

One of the most striking aspects of visual dialogue is that the most concrete and insightful ideas do not usually emerge at the center of a diagram, where the initial abstract concept is placed. Instead, they often appear at the edges, where different ideas meet and contradictions become clear. The margins of a diagram are where insights take shape, where participants notice gaps in their reasoning, and where new possibilities arise.

A conversation might start with a general idea in the middle of the board—something broad like “sustainable design” or “user experience”—but as the discussion unfolds, important and specific concepts start forming in unexpected places. For example, a designer might realize at the edge of the sketch that sustainability is not just about materials but also about labor practices, or that user experience is deeply shaped by cultural expectations that had not been considered before. Or the central concept might be purposefully left blank, a hollow mind map, to quickly get into marginal thinking.

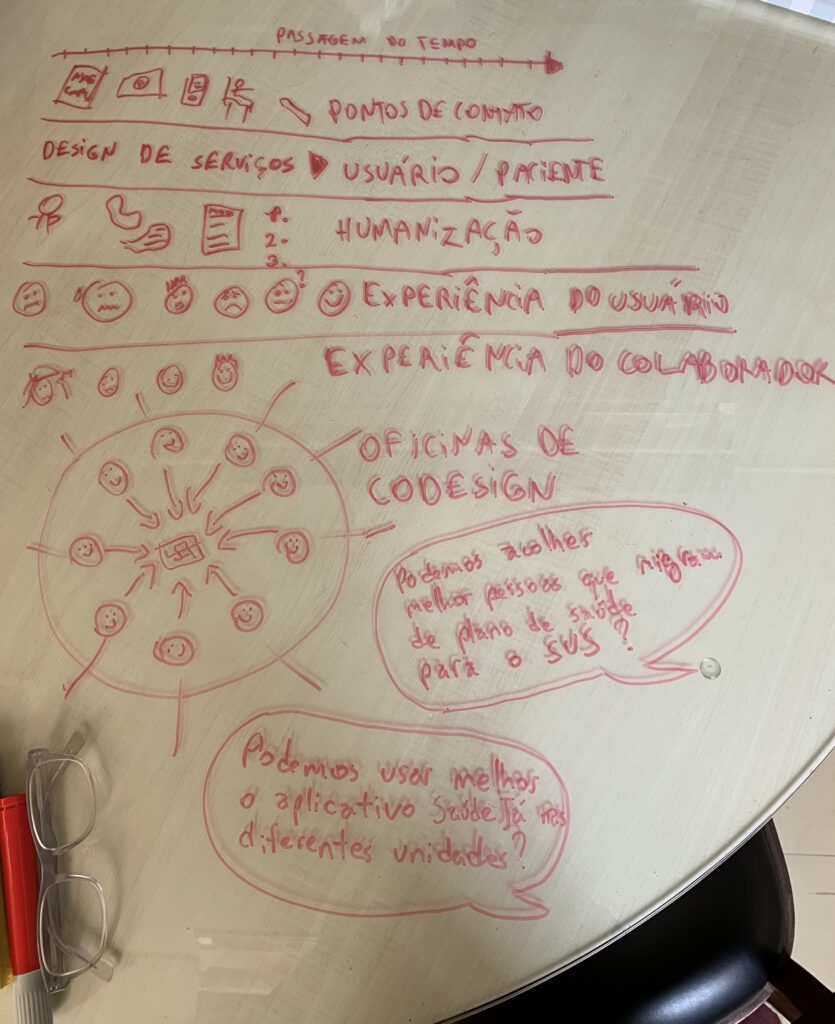

An essential feature of visual dialogue is its multimodal nature—the way it combines speech and drawing to create a richer, more dynamic way of thinking. When people talk, they use language to explain and clarify their ideas, but words alone can sometimes feel linear and limiting. Drawing, on the other hand, allows for a more flexible representation of relationships, contradictions, and alternative viewpoints.

The interaction between these two modes—speech and sketching—creates a dynamic exchange where ideas are not just explained but also explored visually. This is particularly important when dealing with historical and cultural relationships. Time-based elements, such as the evolution of a concept, can be represented through timelines, arrows, or overlays, showing how an idea has changed over time.

At the same time, spatial relationships in a diagram can illustrate cultural differences, revealing how certain ideas are shaped by specific traditions, worldviews, and social structures. For instance, Western diagrams often follow a left-to-right, top-down structure, mirroring reading conventions and hierarchical thinking, while other cultures may favor radial, cyclical, or layered arrangements that suggest interdependence rather than a linear progression.

Furthermore, spatial arrangements can reflect power dynamics: in a collaborative setting, whose ideas take up the most space, remain connected, or become visually dominant? The way visual elements cluster, separate, or overlap can reveal whether cultural perspectives are being integrated or siloed. By critically engaging with these spatial relationships, visual dialogue can move beyond mere representation to actively reshape the way cultural differences are negotiated and understood within a shared space of meaning-making.

In my existentialist advisory practice, change laboratories, and design studios, I use visual dialogue to help develop new concepts over time. When a discussion becomes too abstract, sketching does more than clarify—it actively moves the conversation forward, making invisible relationships visible.

Visual dialogue works better with thick pens and plenty of whiteboards or glass surfaces. Visual dialogue must be spontaneous to the point of not breaking the conversation flow, yet must be encouraged through collaborative policies and team coaching. Visual dialogues produce intersubjective spaces that may stay in place for asynchronous collaboration.

As participants engage with the sketches, they are not just making sense of existing ideas—they are generating fully-fledged concepts. They move concepts around, redraw connections, and recognize contradictions as opportunities for deeper understanding. This process allows abstract discussions to become more grounded, leading to more concrete, actionable insights. Through visual dialogue, conversations do not just lead to conclusions—they lead to discoveries. Instead of merely recording what has been said, sketching becomes a tool for thinking, revealing, and transforming ideas in ways that would be difficult to achieve through speech alone.