Prospective design is a new design approach developed at Federal University of Technology Paraná inspired by Carnegie Mellon University’s Transition Design approach. This short talk explains two of the differences between the approaches: 1) instead of focusing on alternative futures, Prospective Design focuses on alternative presents; 2) instead of framing situations as systems, it frames them as relations that may sometimes form systems but also other totalities that are not systems. We believe that Prospective Design is, in itself, a relation that discovers new possible relations in alternative presents, here and now.

This talk was part of the Transition Design Symposium held by University of Texas Arlington. Watch the full recording for the talks of Terry Irwin, Renata Leitão, and Farzaneh Eftekari.

Video

Audio

Full transcript

Let me begin by explaining why we decided to adopt the concept of prospective design at the Federal University of Technology, Parana. In 2019, we needed to establish a graduate program in design, the first of its kind at our university. However, the National Research Agency informed us that they could only accept proposals that were truly innovative due to budget constraints.

In search of innovative design programs around the world, we came across the Carnegie Mellon University Transition Design Program, which greatly inspired us. Nevertheless, after extensive discussions within our group, we realized that importing a transition design program directly to Brazil wouldn’t suffice. We needed to adapt it to our unique context. In Brazil, translating the term “transition design” posed a challenge, as the concept was not as widely recognized in our public discourse as it was in the United States. Transition design, or “design de transição” in Portuguese, didn’t resonate effectively. Therefore, our first decision was to translate it into another concept called “prospective design” and align it with other relevant design approaches in our country and cultural context.

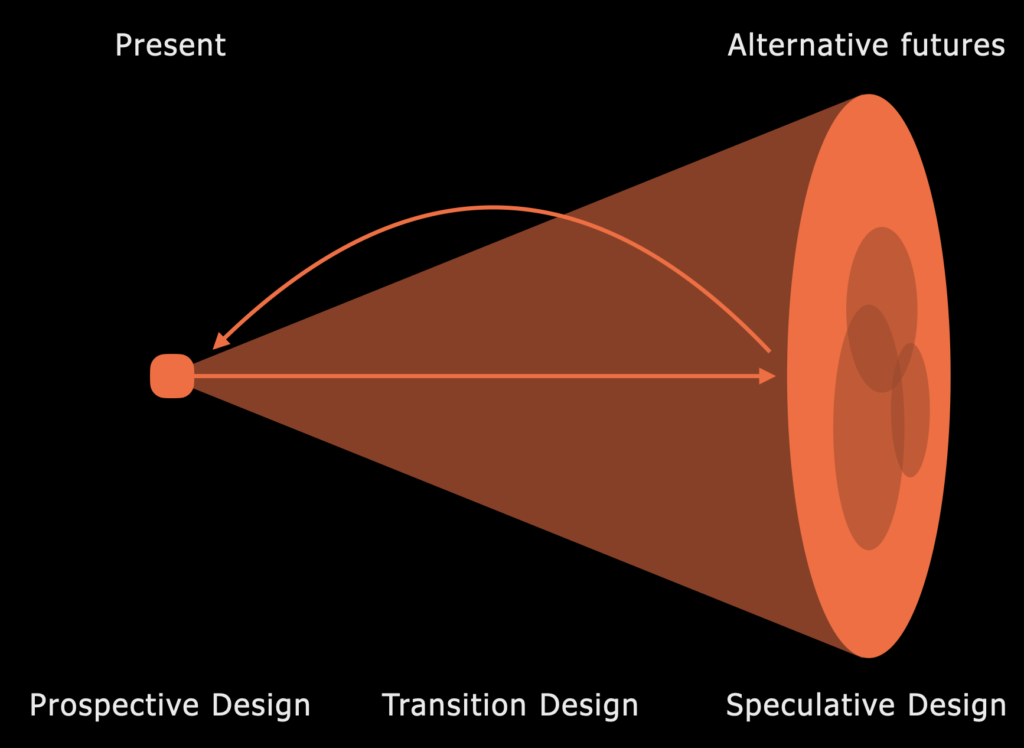

Now, let me outline the conceptual changes we made to tailor this approach to our situation. Transition design primarily operates in the realm of moving from the present time to the future using methods such as forecasting and backcasting. It envisions various future scenarios, ranging from desirable to probable, helping individuals and organizations choose the kind of future they aspire to. In contrast, prospective design places a stronger emphasis on the present.

Historically, in Brazil, we’ve witnessed the domestication of the future—a phenomenon that legitimizes the colonization of the present with unfulfilled promises. Our perspective on the future differs, as it is not something we relentlessly pursue or fully comprehend. Instead, prospective design focuses on transitioning to alternative present states to counter this domestication of the future. I won’t delve deeply into the philosophical aspects, as there’s an upcoming paper titled “Existential Time and Historicity Interaction Design” where we discuss this in detail.

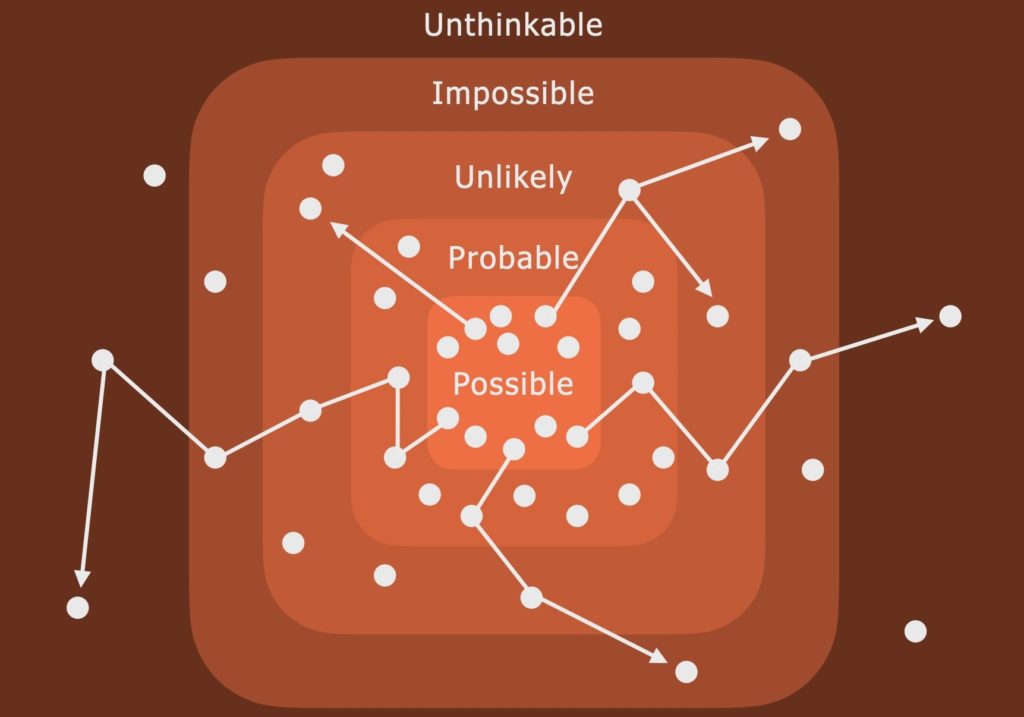

So, what do we mean by “alternative present”? Think back to the categories of futures used in speculative design. We bring these categories into the present, viewing it as a realm of unexplored possibilities that may not yet be apparent but exist beneath the surface. We aim to expand our perception of what is possible, including the probable, unlikely, impossible, and even unthinkable frames of reference.

Practically, prospective design involves identifying these latent possibilities and drawing connections. It’s about shifting from thinking something is probable to exploring the unlikely, and sometimes, even the impossible. By uncovering relationships between the possible and the unthinkable, the unthinkable can become a new possible. We then integrate these possibilities into the current frame of reference within which people are willing to take action.

This isn’t an abstract discussion about the distant future. It’s about what we can do in the here and now, using the resources, institutions, and laws at our disposal. It’s about transforming the relationships between these elements to achieve a more sustainable, just, or democratic alternative presence, depending on our goals. In essence, prospective design is highly motivating, as it’s not a promise of the future but a tangible reality we can shape and transform right now.

When considering design theory, it can be argued that prospective design primarily aligns with the fourth order of design, as articulated by Richard Buchanan. Rather than framing the fourth order as a focus on designing systems or thinking, it centers on the design of relationships. This shift arises because many complex aspects of our world defy adequate description as systems. Entities such as families, religions, and even nations resist straightforward systemic categorization. Attempts to describe them might overlook critical elements. Consequently, we zero in on the more compact concept of “relation,” a common thread that runs through various complex entities.

In this view, a system comprises multiple relations, much like a family, a nation, a company, an activity, and numerous other fourth-order concepts. To better understand the contemporary state of design concerning relationships, we examined the responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020. Our observation was that many designers disproportionately emphasize information and experience, corresponding to the first and second orders of design, while paying inadequate attention to interactions and relationships, emblematic of the third and fourth orders of design.

The consequences of this disparity became evident when less-connected solutions were proposed to address issues arising from the COVID-19 pandemic. This led us to introspect and question why designers were not embracing new relationships. One theoretical explanation for this phenomenon is that designers tend to fixate on individual entities, individuals, and institutions, regarding their objective qualities as the primary scope of possibilities. They are less accustomed to perceiving the interconnections among these entities, resulting in the emergence of relational qualities that rely on various elements interconnected in specific ways.

As a response, we decided to explore new relationships in the present, with an initial focus on recognizing these emergent relational qualities. Designers need to develop an awareness of these qualities. Consequently, we embarked on the development of design projects aimed at cultivating these relational qualities, as seen on the right side of the screen: sustainability, resiliency, equity, solidarity, conviviality, and mobility. These qualities represent novel terminologies for both design students and practitioners, who are typically more acquainted with the objective qualities showcased on the left side of the screen: usability, accessibility, durability, utility, beauty, and clarity. Importantly, these relational qualities depend on the intricate interplay of multiple factors, setting them apart from the more straightforward, individualistic nature of objective qualities.

However, relational qualities are inherent properties of vast entities encompassing not only systems but also complex entities comprising multiple elements and individuals. Designing these relational qualities cannot be the sole responsibility of designers working in isolation at their studios in front of their computers. Instead, they must collaborate with the individuals and entities involved in these relationships. This necessitates fieldwork and active engagement with the relationships, recognizing that these relationships evolve over time and are not immediately graspable.

Allow me to provide insight into some of the projects we are currently undertaking in Brazil, drawing inspiration from these relational qualities and the concept of alternative presence. The Corais Platform, which has been in development for over a decade, serves as a digital infrastructure enabling various relationships, including those within the solidarity economy. This involves the creation of local banks and alternative currencies, rooted in a different economic ethos, one not driven by competition and personal gain but centered on local achievements and community bonds, fostering solidarity.

In collaboration with numerous cultural producers across Brazil, we designed a digital currency feature that empowered a wide range of new businesses. For instance, a theater university facing government budget cuts leveraged this platform by printing their own money, enabling them to continue their classes. It’s important to clarify that we do engage in the design of tangible products in prospective design, but these products are designed to facilitate these relationships. The relationships themselves are the ultimate goal, not the products.

For example, we created a book titled “Coralizando,” which shares the collective experiences of various actors involved in the Corais Platform. While the book is a tangible product, its primary purpose is to enable new relationships. Subsequent collectives have read the book and used its information to shape their own relationships. In essence, our focus in prospective design is always on connecting things and people, fostering meaningful relationships.

Another example closely aligns with what graduate students in design can accomplish. This particular project, although initiated by an undergraduate student, exceeded the typical expectations for graduate-level work. The student engaged with rural women coffee workers and discovered that their labor often went unrecognized. Their products lacked acknowledgment, and they were unsure how to raise awareness among consumers and society about the invisible work of these women.

In response, the designer reached out to both rural and urban women coffee workers, including baristas and coffee dealers, posing the question: “Were you aware that the coffee you sell is produced by women in rural communities?” This revelation sparked enthusiasm, as it presented an opportunity to unite against sexism—a shared challenge in the coffee industry. They formed a coalition and even influenced a public policy under development by Maria Leticia, a local councilwoman. The policy was designed to enhance workplace safety for women but specifically addressed the needs of barista workers, thanks to the collaboration of these determined women.

Within our department, we’ve undertaken exercises aimed at comprehending new relationships through legal and material means, uncovering latent relations that have yet to be realized. For instance, we established the Laboratory of Design Against Oppression (LADO) following conversations with three different professors, including myself, who were already engaged in design projects addressing oppression. Additionally, we initiated Prospectina, a collaborative workshop involving multiple departments at our university. This workshop seeks to envision the future of our university in the post-pandemic era.

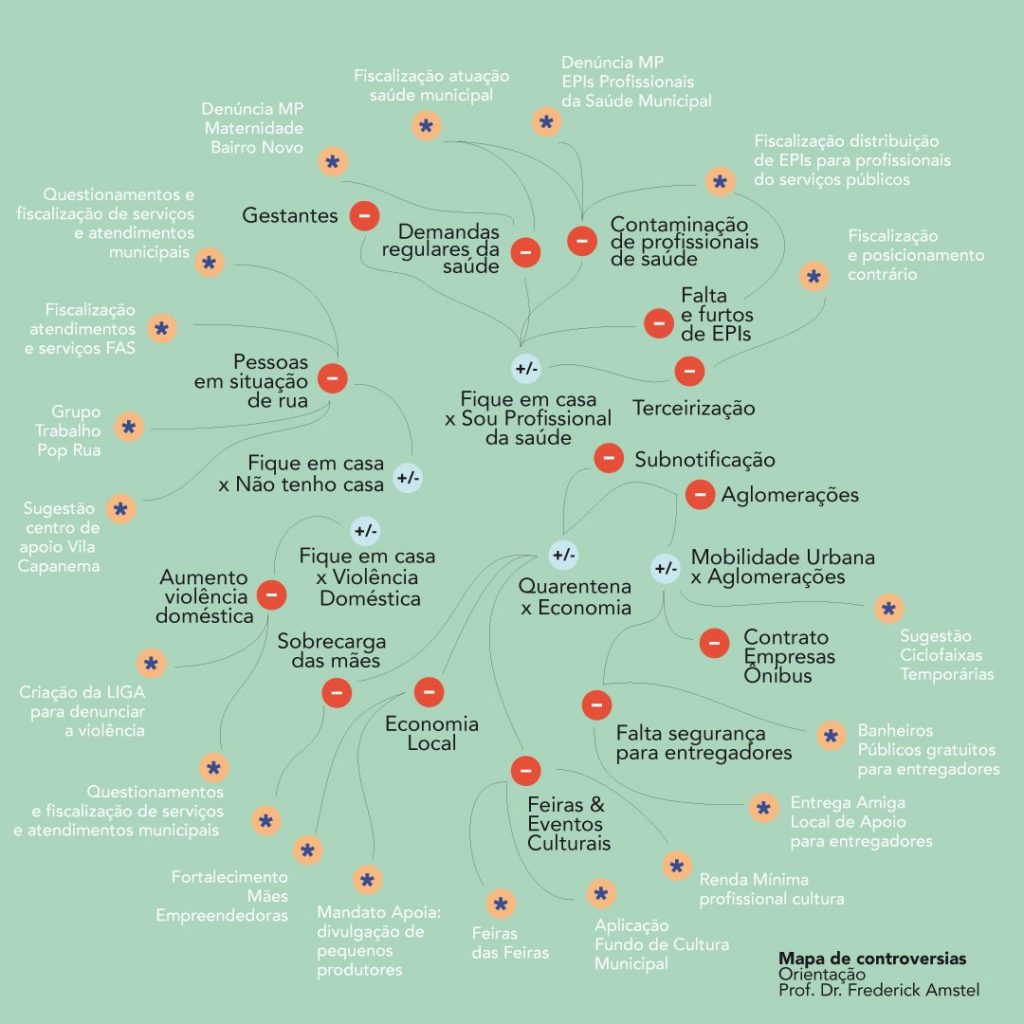

While we are engaged in various initiatives, I will focus on community engagement as it plays a pivotal role in driving change and transitioning toward an alternative presence. Once again, Maria Leticia, the councilwoman, engaged in a conversation with us about the cost of women’s labor. During the COVID-19 pandemic, we collaborated to create a map highlighting the controversies surrounding the pandemic in Brazil. She used this map to understand and address the contradictions that surfaced. For example, we mapped the connection between the imperative to stay home and the lack of proper housing or even homelessness. We also explored the prejudice faced by those with the disease, particularly individuals who appeared to be sick but were not.

For instance, racial biases led some to assume that individuals with darker skin were more dangerous due to perceived hygiene issues—a clear manifestation of racism intertwined with living conditions. Intervening in the complex and uncertain context of the COVID-19 pandemic presented significant challenges. Maria Leticia focused her efforts on specific points and contradictions where meaningful action could be taken. Our students used the same map to launch their own outreach initiatives.

One example was the discovery that the official public communication campaign was not effectively addressing the needs of people living on the outskirts of the city. Many of these individuals were black or brown, yet the campaign featured predominantly white individuals. This campaign failed to resonate with these communities, as it did not account for their specific challenges, such as water scarcity during that period. Some homes lacked a water supply, making basic hygiene recommendations difficult to implement. Our students intervened by engaging with marginalized communities and employing popular communication and design approaches to address their unique needs.

It’s important to clarify that while we produce various products, graphic design materials, experiences, and services, these are not our primary objectives. They serve as mediators, enabling us to achieve our ultimate goal: uncovering relationships that are already possible within our alternative presence here and now. In summary, prospective design centers on identifying what is feasible at this very moment and actively harnessing existing relationships. Thank you for your attention.

References

Van Amstel, Frederick M.C and Gonzatto, Rodrigo Freese. (in press) Existential time and historicity in interaction design. Human-Computer Interaction.

Van Amstel, Frederick M.C.; Guimarães, Cayley; Botter, Fernanda. (2021). Prospecting a systemic design space for pandemic responses. Strategic Design Research Journal, 14(1), pp.66-80.

Van Amstel, Frederick M.C.; Gonzatto, Rodrigo F.; Jatobá, Pedro G. (2021). Redesigning money as a tool for self-management in cultural production. Proceedings of the II PIVOT 2021 Virtual Conference. Design Research Society. – Jul 28, 2021 – Jul 27, 2021

Eleutério, Rafaella P. and Van Amstel, Frederick M.C. Matters of Care in Designing a Feminist Coalition. (2020). In: Proceedings of the 16th Participatory Design Conference. Manizales, Colombia.

Vale, G.; Zanotto da Silva C., Cabral, M; Moniz, M; Rodrigues da Silva, C; Van Amstel, F.M.C. (2020) Perifa consciente: comunicação popular em comunidades vulneráveis de Curitiba (Conscious Periphery: popular communication in vulnerable communities of Curitiba). Revista Tecnologia e Sociedade, 16, 111-117.