Abstract: The possible is relatively constituted to what is meant to be impossible. Whenever someone does something formerly known to be impossible, the possible expands, and a new frontier appears. Expanding this box is not trivial, though. Contradictions binding the dos and don’ts demotivate any naïve attempt to design at the border. Expansive design is this practice identified by Dr. Van Amstel in his Ph.D. thesis of incorporating contradictions in design and harnessing their potential. In it, the people who live at the border gather to represent, understand, and change these contradictions, releasing their tension until the impossible becomes possible. The thesis work found ample evidence that games can support this expansive representation process. Subsequent design research has shown that theater, handmade models, data visualization, and movies can also do that. This lecture presents selected examples of expansive design projects studied in the Netherlands, UK, and Brazil. The lecture concludes with the prospect of doing expansive design in the US.

Visiting Designer Talk in the Graphic Design/Design & Visual Communications Speaker Series, School of Art + Art History, University of Florida.

Video

Audio

Full transcript

Navigating between the realm of the possible and the impossible, today’s talk draws insights from my PhD thesis, defended at the University of Twente in 2015. My primary focus was understanding how design could assist non-designers and what they could potentially learn from design that could enrich their practices. I introduced a concept termed “expansive design”, which I’ll elaborate on.

Before diving deep, let’s place this lecture within the broader debates in the design domain. There’s a burgeoning conference in the Netherlands named “What Design Can Do“. Its core objective is to encourage individuals to perceive design from a wider lens — not merely as a craft for designers or their clientele, and not just for user-centric design, but as a holistic human endeavor to address societal challenges. This includes tackling substantial issues like climate change, social disparities, and political unrest. The conference exudes positivity and vision.

However, it’s also met with certain criticisms pointing out the potential oversimplification of some design solutions. Take, for instance, an upcoming book by design critic Silvio Loruso: “What Design Can’t Do”. He reminds designers that the challenges they now aim to address have been subjects of study in various fields for ages, with no straightforward resolutions. His book, aptly titled in response to the conference’s name, sheds light on the boundaries of design’s capabilities.

This lecture is positioned between these two perspectives. My curiosity leans less toward what expert designers can achieve and more toward what people not necessarily trained in design might achieve in collaboration with or without professional designers. I posit a fundamental question: how can people do what design cannot do? With pressing challenges like climate disparities, societal inequality, and political upheavals confronting us daily, there’s an evident void in how design addresses these. As Silvio Loruso underscores in his book, our response must be self-critical.

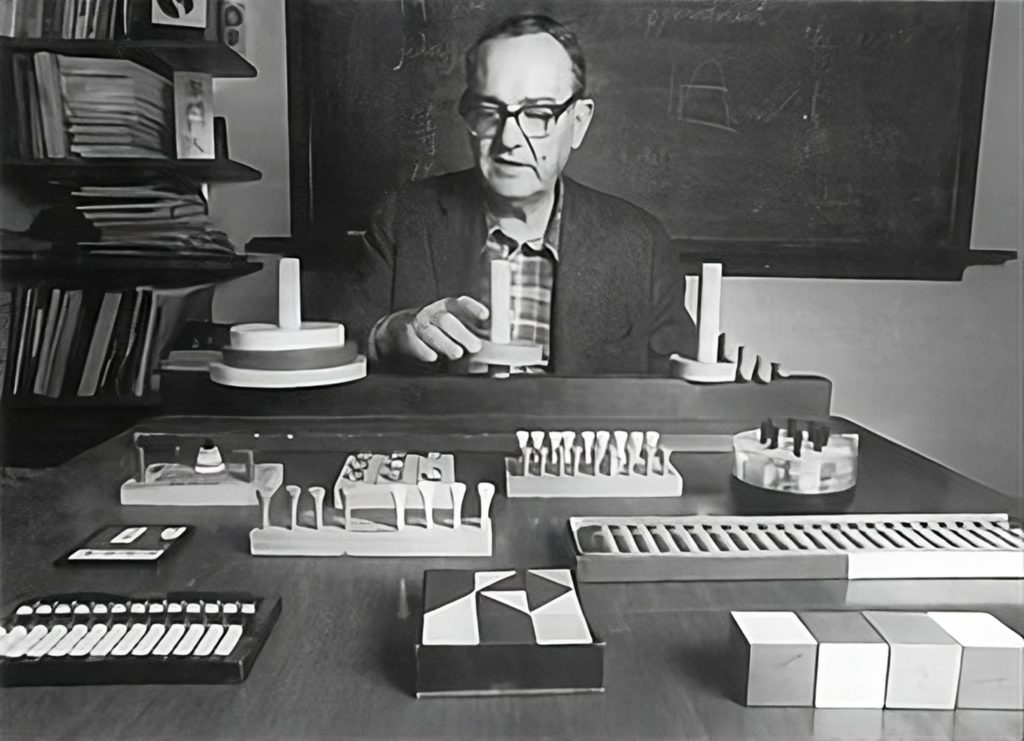

Let’s come back to the foundational roots of design. From the myriad of definitions available, I’ve picked one specifically for critique but also as a cornerstone for my understanding of design. This perspective comes from Herbert Simon’s influential, albeit debated, book “Science of the Artificial.” He suggests that design is inherent to all – not limited to graphic or industrial designers, but extends to engineers and professionals across fields. He believes that anyone strategizing to transform a situation into a preferred one is designing.

Simon’s portrayal, represented by this picture of himself learning on games, is a metaphor for understanding design. Yet, it’s crucial to note that his emphasis is on mathematical games with set outcomes or limited variations. On the other hand, my intrigue is rooted in games that continually reshape the realm of possibilities and create new avenues.

However, a potential constraint with Simon’s view is that changing the possible seems impossible when the possible is reduced to individual preference. Simon’s perspective stems from a historical context where accommodating varying preferences wasn’t challenging, thanks to significant economic growth. It was the era of mass production evolving into mass customization. Industrial design, both in practice and academia, was burgeoning. The diverse car designs, known as styling, epitomized this era. Vehicles were no longer just modes of transportation; they became statements of personal ideology and taste, reflecting the design ethos of that period.

The oil crisis and various late 60s and 70s upheavals made previous approaches unsustainable. Political disturbances peaked, with student-led protests, notably in France, articulating the global mood. The slogan, “Be realistic, demand the impossible,” summed up the progressive mindset: we can’t continue on our current path without devastating our planet. The challenge became, can we reduce our consumption and maintain quality of life? The 1968 student movement posed such questions.

Among the impactful initiatives from this era was the Netherlands’ Provo white bike plan. People painted their bikes white, turning them into communal property, free for anyone. This precursor to modern bike-sharing influenced the Netherlands’ shift towards pedestrian-friendly policies. However, despite such innovative ideas, much of the 1968 movement’s momentum waned over time.

The 1980s marked a turning point as neoliberalism dominated political and economic spheres. Margaret Thatcher’s proclamation, “There is no alternative” (TINA), emphasized a commitment to privatization and reduced state intervention. For many, this signaled an endorsement of neoliberalism and an assertion that capitalism had no viable alternatives.

Capitalist designs crushed the existing socialist alternatives. The Chile democratic socialist approach, for example, aimed at transitioning to socialism without resorting to the violent coups observed in places like the Soviet Union or Cuba. However, this vision was short-lived, with external interference from other nations, including Brazil and the US. A significant part of Chile’s plan for responsive socialism was Cybercyn. Rather than the traditional five-year plans of the Soviet Union, Chile adopted a dynamic planning method. This system used real-time data from production and consumption unions, visualized in the futuristic Operations Room. The coup of ’73, which terminated Chile’s socialist aspirations, also destroyed this remarkable initiative. Thanks to research done by Eden Medina from MIT and the thrilling podcast of Eugeny Morozov’s, The Santiago Boys, the general public now has access to the project’s legacy.

Many believe that there’s no viable alternative to capitalism or advanced technology. Yet, Chile’s example shows how technology and design can foster more egalitarian alternatives over pure competition. Presently, the global situation appears more bleak than the ’70s and ’80s. We’ve lost the checks and balances of the Soviet Union the democratic socialist model of Chile, and even Cuba’s viability is waning. As Mark Fisher articulates in his book “Capitalist Realism”, it seems more conceivable to envision the world’s end than the end of capitalism. This sentiment captures the dire urgency of our times, particularly when considering the implications of climate change under the weight of unchecked capitalism.

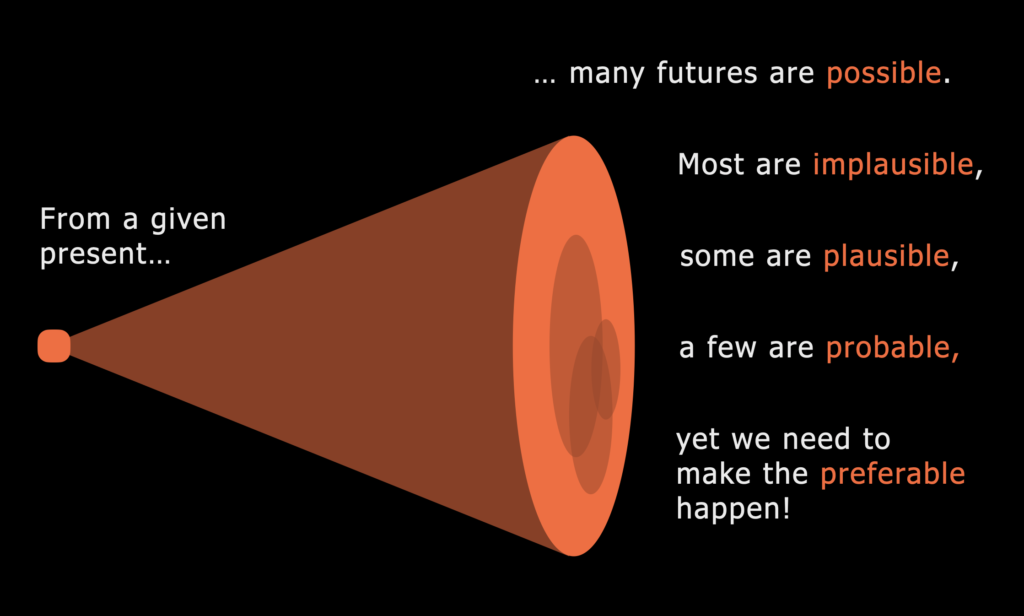

And how is design responding to this today? Well, speculative design has been quite proactive in broadly envisioning our society’s future. However, it hasn’t been focused on changing this future significantly. Its primary goal is to raise awareness about the potential consequences if we don’t alter our current course of action and the probable future becomes actual. Unless we insist on and demand the future we prefer, such as a world without atomic weapons, we might find ourselves on a perilous path.

How does speculative design achieve this? It creates objects like the atomic plush toy designed to help us become more accustomed to living in a world under the constant threat of nuclear annihilation. It’s important to clarify that speculative designers don’t desire such a scenario; instead, they use these objects as tools to encourage societal reflection on the kind of world we want or whether we want a world at all. While this approach may seem somewhat fatalistic, it stimulates critical thinking.

However, it’s worth noting that speculative design hasn’t fully explored the boundaries of what’s possible. It typically operates within a future cone model (Bezold and Hancock, 1993), speculating on various futures based on our current present. These futures are categorized into implausible, plausible, and probable scenarios, with the latter often including dire predictions like the world’s end and other catastrophes. Speculative design uses this model to draw attention to the preferred possibilities we should strive for and actively work towards.

Nevertheless, this approach can be seen as somewhat conservative in its outlook on the future, as it gives the impression that we can’t envision anything beyond what falls within this future cone, limiting our perspectives and possibilities. The true potential of speculative design lies in its ability to expand our conception of the future from the merely probable to the realm of the possible. While it may be probable that we end up self-destructing in an atomic nuclear war, it’s also entirely possible that we can avoid such a disastrous outcome.

Now, I’ll present a bit about expansive design, a practice I identified and further developed in my PhD thesis. It differs somewhat from speculative design, though I draw inspiration from it. Expansive design is more focused on the present, not so much on the future. It centers on what we can and cannot do right now, navigating the space between the possible and the impossible.

In essence, expansive design allows us to explore not only possible presents but also impossible ones that we can challenge. It resonates with the motto of the students from ’68: “We can be realistic and demand the impossible.” This motto encapsulates one perspective on what expansive design represents. However, we aim to move beyond the ephemeral nature of the Situationists’ practices in ’68. Instead, we seek to establish enduring situations by pushing the boundaries of what’s possible.

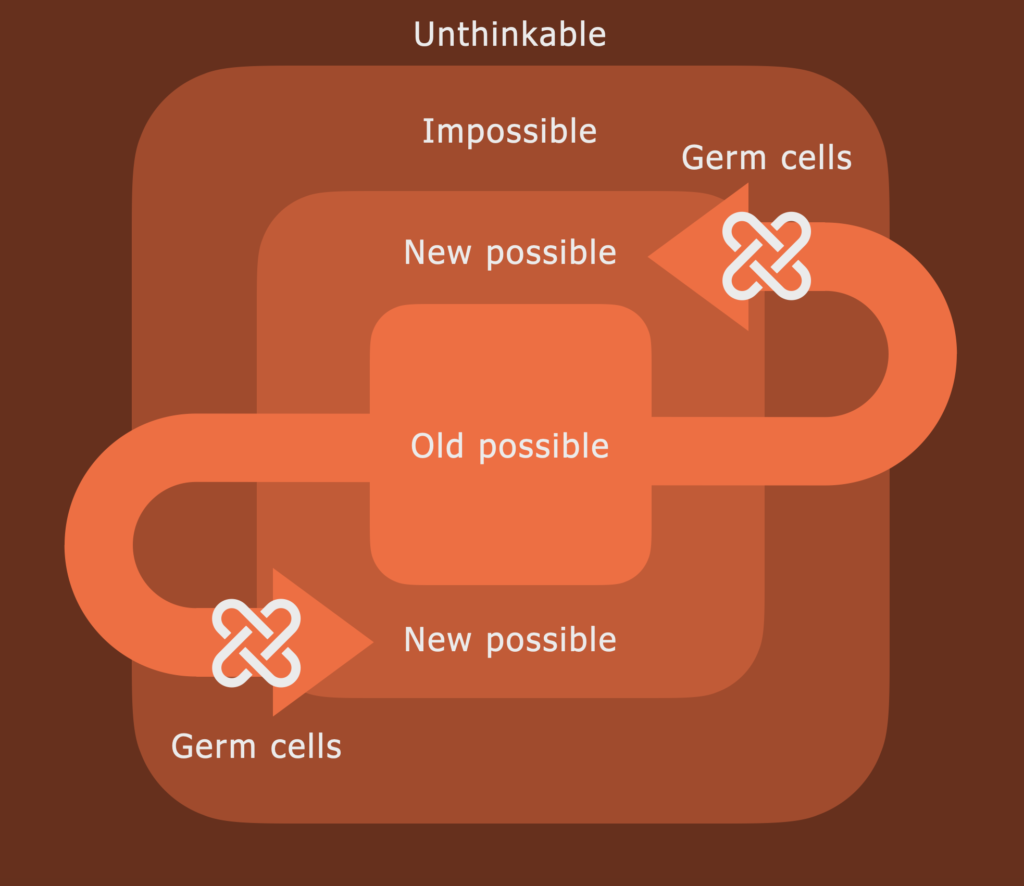

Instead of organizing our ideas around time, as in the Future Cone model, we use space to redefine the relationship between the possible, the futures, and the present. Consider the possible as a box of actions we currently deem feasible, while the impossible encompasses actions or events considered unattainable. You might recognize this concept from various cultural references or internet memes. “It always seems impossible until it’s done” is often attributed to Nelson Mandela, though the exact source of these words is debated. Nevertheless, it’s fitting because he accomplished remarkable feats, like ending apartheid in South Africa, which once seemed impossible during his incarceration. Analytically, Mandela’s quote suggests that the possible can become outdated, making room for new possibilities that lie between the impossible and the possible.

Within this sweet spot, expansive design thrives and nurtures a practice that often resembles thinking outside the box. There’s certainly a discourse out there promoting this idea. However, I’d argue that it’s quite the opposite. Expansive design is really about thinking inside the box because the goal is to change and remake that box. How can we transform the box if we don’t delve into its limitations and truly understand them?

This type of thinking outside the box aligns more with speculative design, and, unfortunately, much of speculative design hasn’t been very effective at changing our current situation. Speculative design often warns us about a future that feels disconnected from our present reality. On the other hand, it can be too fatalistic, leaving us feeling powerless, as if we can just wait for the world to end without taking action. Such a mindset is precisely what we aim to avoid with expansive design.

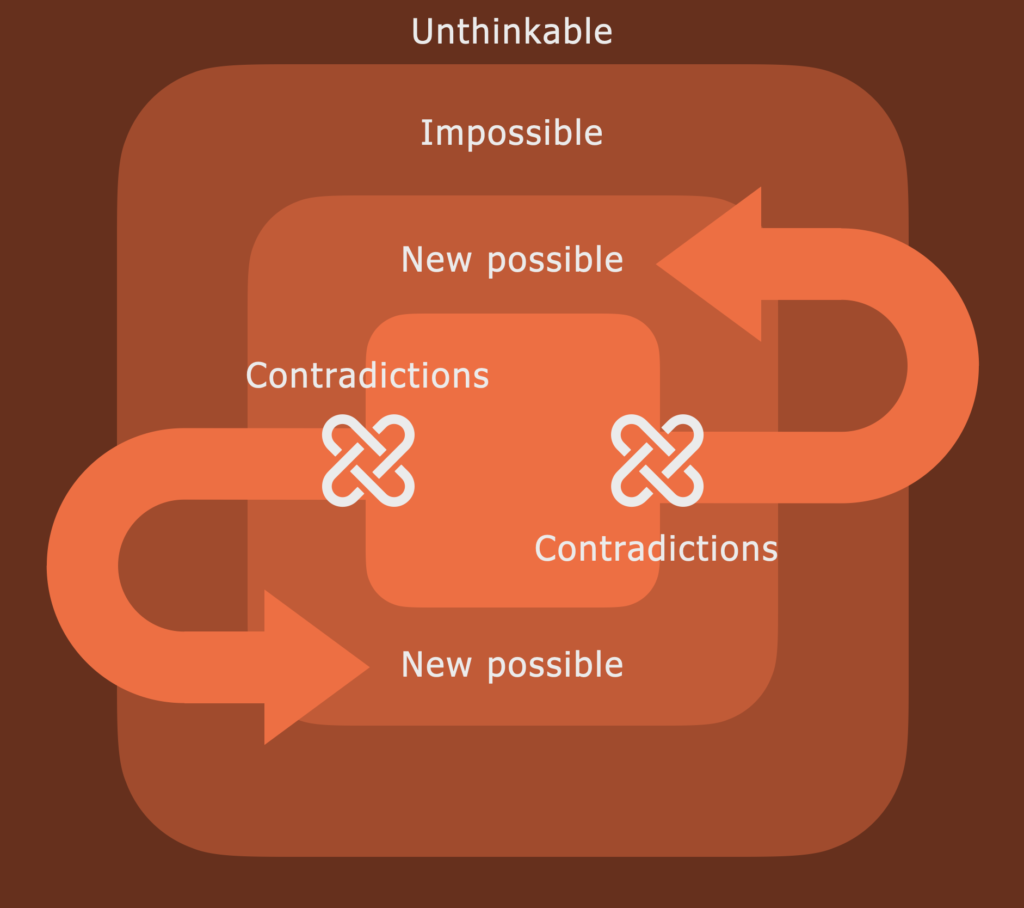

Expansive design does engage in contemplating the impossible, even venturing into the unthinkable, but it ultimately returns to the familiar possible. We revisit the existing possibilities and introduce friction, allowing new possibilities to emerge. However, during this process of reimagining the box, we come to realize that it’s not empty. Remaking the box means confronting the contradictions that define the do’s and don’ts, essentially reproducing the same boundaries that created the box in the first place.

This box is constructed not only from abstract thought but also from tangible factors that concretely limit people’s actions. This is the challenge that expansive design must confront. It’s not a simple task; it’s not just about thinking outside the box; it’s about grappling with these contradictions. I’ve attempted to represent this concept graphically to illustrate the way contradictions bind the possible and the impossible while creating tension and movement, which may eventually lead to change.

Expansive design operates by carefully releasing this tension, referred to as contradictions. We achieve this by designing what I call germ cells, and I’ll explain this concept shortly. These germ cells bring back those contradictions that were binding the possible and the impossible and reintroduce them into the realm of the new possible. By doing so, we can view the same contradictions in a different light and potentially foster change within society, not just among designers.

Technically, a germ cell, a theoretical concept included in Cultural Historical Activity Theory (CHAT), is the smallest unit of social relations that can generate new activity from a set of historically entrenched contradictions. It takes the form of these contradictions, allowing us to sense, feel, touch, and grasp them, rather than merely relying on intuition or fear. However, the form of germ cells remains ambiguous, enigmatic, unsettling, open-ended, controversial, yet also playful.

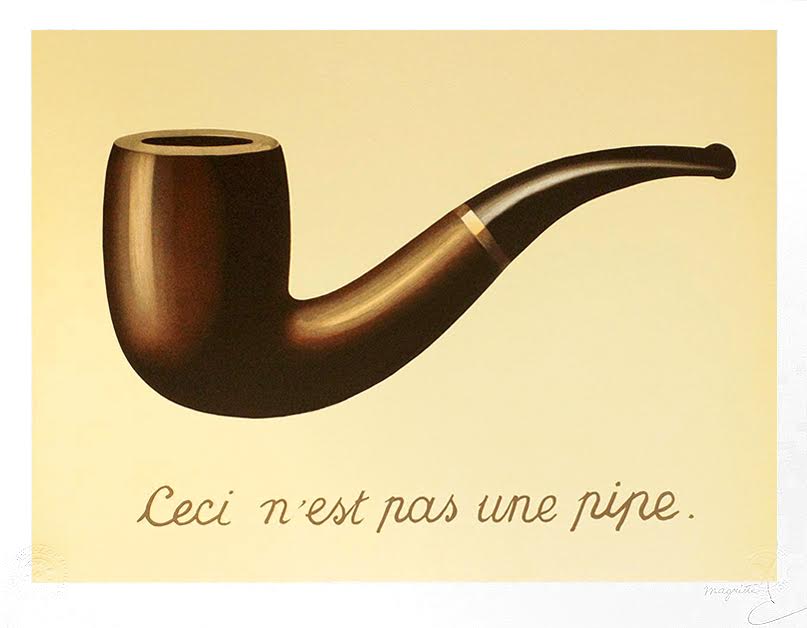

Now, I expect the following examples to illustrate this concept further. Let’s begin with what I consider one of the most intriguing germ cells I’ve come across – René Magritte’s (1928) painting, “The Treachery of Images.” Magritte, a surrealist painter from the ’20s, managed to encapsulate the entire history of art and even human language in a single picture. The painting features a pipe, beneath which the words declare, “This is not a pipe.” The words contradict what the picture depicts, but the image itself is also not a pipe; it’s merely a representation. However, we frequently treat images as the actual objects they represent. Our conversation right now, for instance, relies on these representations. I’m not currently an associate professor at the University of Florida, nor am I am really speaking to you through this computer. We can have this conversation only because we agree on these representations and accept the contradiction that we can’t be in unmediated reality. That is why images are inherently deceptive and treacherous. They stand for reality to the point of becoming the reality we live by.

Surrealists explored other germ cells that captured more process-oriented contradictions rather than static representations. These processual germ cells delve into more intricate and integrated contradictions. For example, they addressed the complexities of collective creation and the unpredictability of human behavior, including what others think while you’re thinking. One such technique is the “cadavre exquis” or “exquisite corpse” in English. In this collaborative drawing game, you’d draw a portion of a drawing and then fold the paper so the next person can’t see your contribution. They would continue the drawing based on only a tiny part they could see. After all parts were drawn blindly, the final creation would be revealed to everyone. These drawings often featured surreal and contradictory elements, aiming to bring unconscious contradictions into the consciousness of society.

Inspired by Surrealism, Augusto Boal developed Theater of the Oppressed, an approach to using theater to challenge societal oppression. Among the tools used, Boal devised dramatic games that are pretty similar to the surrealist games. They expose the contradictions of oppression and allow us to use our bodies to break free from restrictive postures that limit fixed meanings. In his book “Stop C’est Magique,” Boal explains why he draws so much from Surrealism: breaking free from oppression requires sensing the impossible reality behind the possible reality.

I’ve been deeply involved in Theater of the Oppressed, especially at the Centro do Teatro do Oprimido in Rio de Janeiro, where I’ve spent considerable time. In one photo, you can see me as a sexual abuser at a party. In this situation, I felt uncomfortable because I didn’t identify with that role. However, I recognize that people like me, white, heterosexual, and often seen as “alpha males,” frequently behave in such ways. I can’t escape being cast into that role because society often imposes that onto me. Engaging in this type of theater helped me understand why people in Brazil, especially women, black individuals, and indigenous communities, often view me as part of the oppressor’s side and are apprehensive about interacting with me. This theater has been instrumental in understanding my socialization on the oppressor’s side and how I can ally with the oppressed.

Playing the oppressor’s role and embodying their contradictions allows others to practice resisting oppression and attempting to liberate themselves. As an oppressor character, I remain oppressive and attempt to thwart their efforts to break free. However, I won’t delve too deeply into Theater of the Oppressed here, as my main aim is to showcase various methods of expansive design. While we draw inspiration from Theater of the Oppressed and Surrealism, we also employ various other approaches to expand the possible.

In essence, expansive design aims to carefully release accumulated tension in contradictions, opening up new possibilities for collective action. There are numerous ways to achieve this, with theater being just one avenue. We strive to generate these germ cells, and I’ll present various germ cells to offer you a glimpse of the possibilities. I won’t go into great detail for each, but I can delve deeper into any of these cases if you have specific questions.

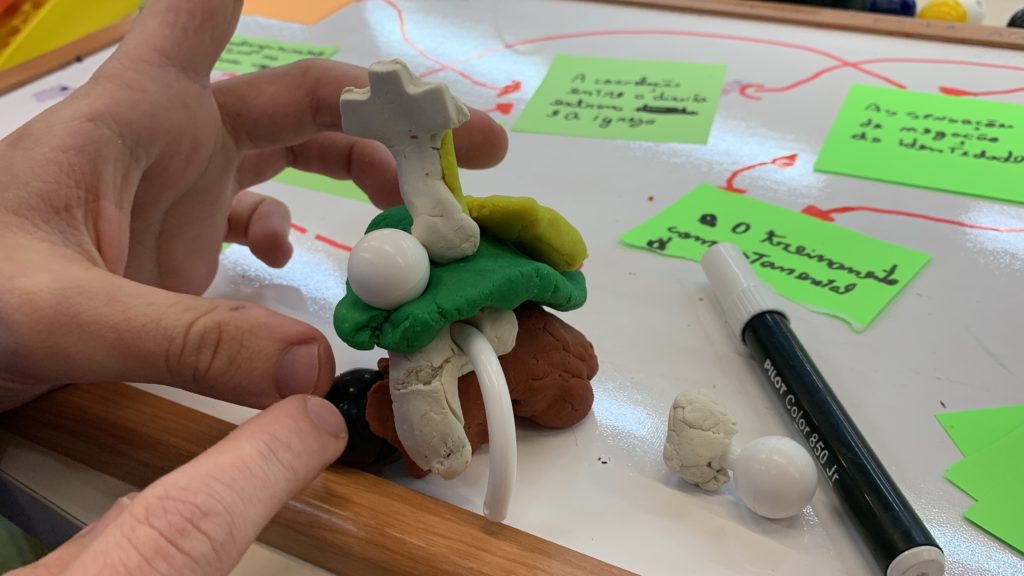

Let’s start with some of the simplest forms: handmade germ cells. These involve using materials like plasticine or clay to intuitively model contradictions without relying on words, which can often be challenging for grasping contradictions. For example, a student at the Federal University of Technology was trying to understand why black people in Brazil might vote for anti-black politicians like our former president, Jair Bolsonaro. This contradiction puzzled him, but he used this handmade model to make sense of it. Through this model, he could explore the role of religion and the fragmented communication facilitated by social media in this voting behavior.

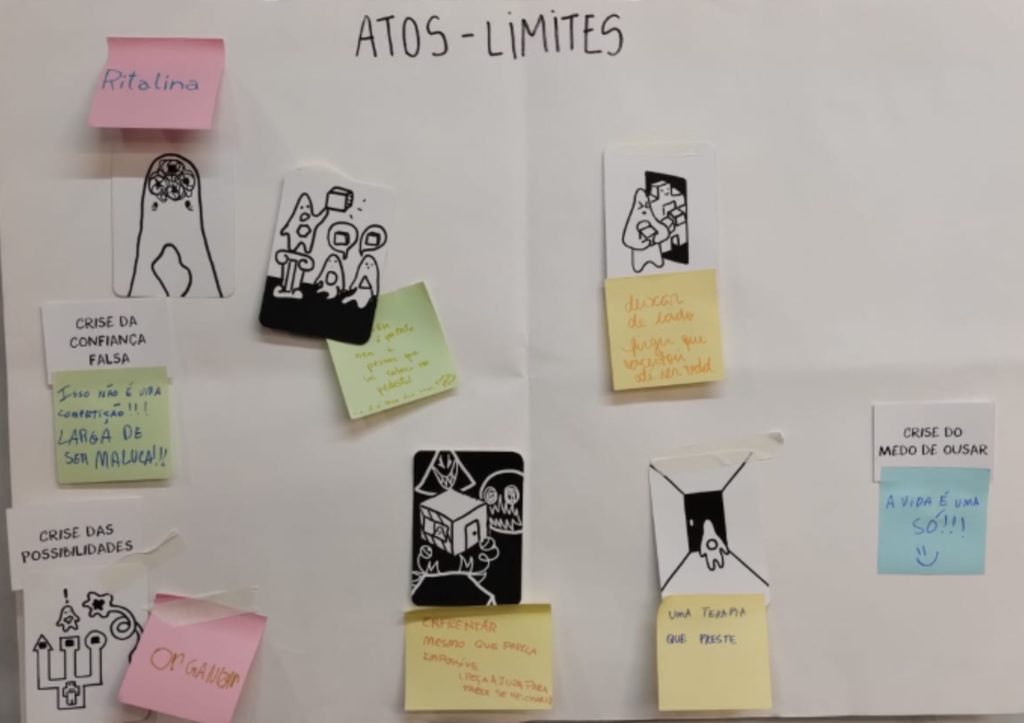

Next, we have germ cell images, which draw inspiration from surrealist imagery and incorporate information design principles. One noteworthy project comes from Alanis Zukowski and Vitoria Kosake, former students in our graphic design program. They created a “crises deck” to share their experiences with other students. It allowed them to discuss existential crises, such as working for capitalism that harms our world or acting against it while struggling to pay their bills. Through facilitated dialogues using these cards, they discovered that many students faced similar crises and could identify social factors contributing to them.

Lastly, during the pandemic, we had to adapt to online workshops. In one such experiment, we used emojis to convey complex ideas, relying on the inherent ambiguity of emojis. Expressing contradictions through a combination of emojis allows us to navigate nuances that reason alone cannot fully resolve. Emotions play a significant role in grasping these nuances.

Now, let’s explore metaphorical models, mainly drawing from the Lego Serious Play methodology but adapted to dialectical thinking, which forms the basis of expansive design. We’ve conducted several workshops with a utility company in the Paraná State. This company grappled with contradictions, such as the need to expand its energy generation sources while facing finite natural resources. They used a Lego Serious Play model, a metaphorical approach, employing, for instance, the gator, a beloved symbol in the University of Florida, to represent the power, force, and menace in which nature impacts humanity.

After constructing this model, they aimed to convey these contradictions to young entrepreneurs, particularly those interested in entering the energy sector. They aimed to stimulate the transition to smart grids, integrating various energy sources, including water, solar, and wind. However, they recognized that current policies were disadvantaging lower-income individuals, as the prices of water-generated energy rose due to wind and solar subsidies. They challenged the entrepreneurial ecosystem to devise more socially equitable energy distribution solutions.

Let’s look at examples of integrating Theater of the Oppressed in design. In this unique adaptation for the Design and Culture course, students embodied the contradictions of designing a garment equivalent to the female bra, but for males. They called it the “scrotien,” a play on words related to the Brazilian term for bra, “soutien.” In a humorous interview scenario, the scrotien itself spoke, claiming its purpose was to keep the male scrotum healthy and prevent it from succumbing to the effects of gravity over the years. They tapped into the discourse that justified the use of bras for women and created a range of products and graphic imagery to promote the advantages of using the scrotien, including a “dry fit” version for sports.

While this project may appear amusing, it also highlights the gender inequalities deeply ingrained in fashion design that society often accepts as the norm. The students pushed the boundaries to question why bras are expected garments for women but not equivalent garments for men. This isn’t speculative design; it addresses present-day issues, challenging individuals, particularly men like myself, to confront the implications of such projects.

Next, we dive into more complex germ cells like games. These require more time and effort to develop but allow for representing numerous contradictions within a game system. In my Ph.D. thesis, alongside the book you saw earlier, I introduced a board game called The Expansive Hospital. This playful game encapsulates all the contradictions I encountered while studying hospital design projects in the Netherlands. When I later brought this game to Brazil, I found that the same contradictions were also prevalent here. These included stakeholders’ disagreements on what was best for the hospital, with personal or company interests often taking precedence over the hospital’s best interests.

We’ve devised several other games, but I’ll only provide one more example. Thinking Inside the Box, developed in partnership with GD Innovation, is a card deck for entrepreneurs to develop new skills without sacrificing autonomy. Many entrepreneurial programs follow strict step-by-step processes, limiting entrepreneurs’ ability to design their paths and develop their unique approaches. With this game, it’s different. Each card represents a possible action for entrepreneurs to take. By accumulating points through these actions, they can continually assess their team’s position within the spectrum of skill development.

The game helps entrepreneurs understand how specialized they are in the central aspects of entrepreneurial activities and which specializations may not be relevant. The primary contradiction this game addresses is the balance between guidance and autonomy. Guiding a new entrepreneur is essential, but excessive guidance can hinder the development of the necessary autonomy, a crucial quality for successful entrepreneurship. This game is available to the public and if you read Portuguese and wish to translate it, you can find it as a Creative Commons project online. This game is one of the many spin-offs from the utility company startup acceleration program I mentioned earlier.

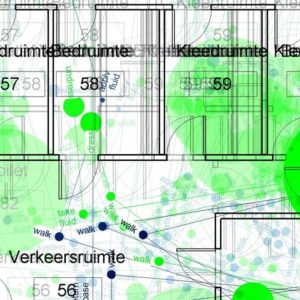

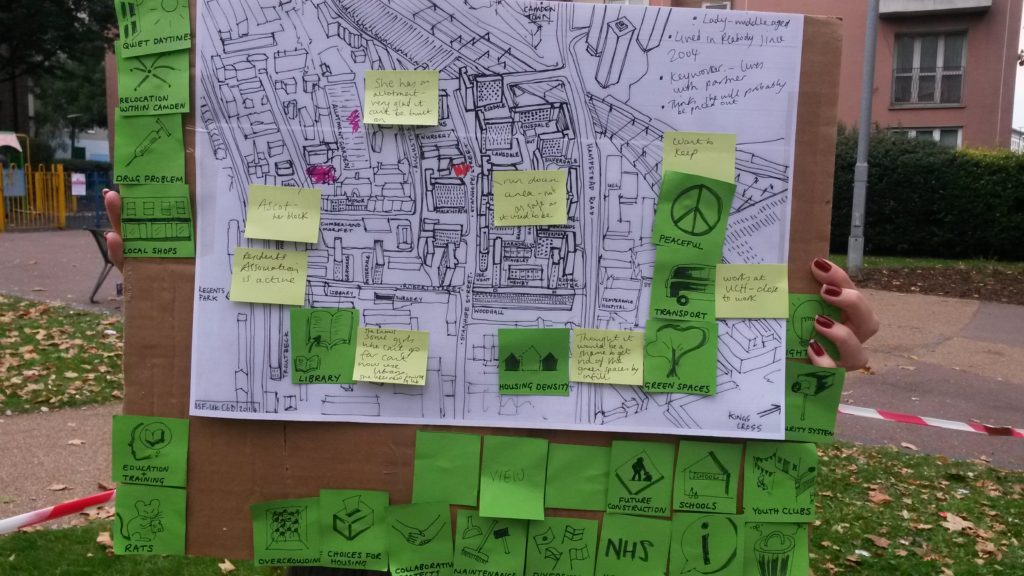

Moving on to germ cell maps, these maps are created collaboratively, with people who inhabit a particular space invited to contribute their contradictions to the map. For example, in the Change By Design Workshop 2014, Architecture San Frontières UK organization inquired into a public housing unit slated for demolition as part of a significant infrastructure project. Residents wanted to express what they would lose with the demolition, so they partnered with the organization to summarize their demands and needs. As part of the team, we invited residents to join us for a chat about their experiences over a cup of tea. We used a game to record these experiences, allowing participants to choose icons and share stories on the map of the housing unit. Later, these contributions were compiled to generate an overall view of the main issues and potential trade-offs they could negotiate in exchange for accepting the demolition and moving to another location.

In a more recent example of community design, we collaborated with the Uniperifa Collective to organize actions on the outskirts of Curitiba. Residents from the outskirts of Curitiba, who were part of Uniperifa, came to the university. We played a mapping game to identify the most tense contradictions in the region where they lived. They discovered that the community center was the focal point of this contradiction because it wasn’t properly maintained, yet many community members had used it. It had become a symbol of the community’s inability to engage in community work. To address this, they decided to renovate the center to initiate further community initiatives. Our students participated by doing tasks such as painting and fixing furniture, which extended beyond the typical training of graphic designers. This collaborative effort opened up possibilities for more graphic design-related projects in the future.

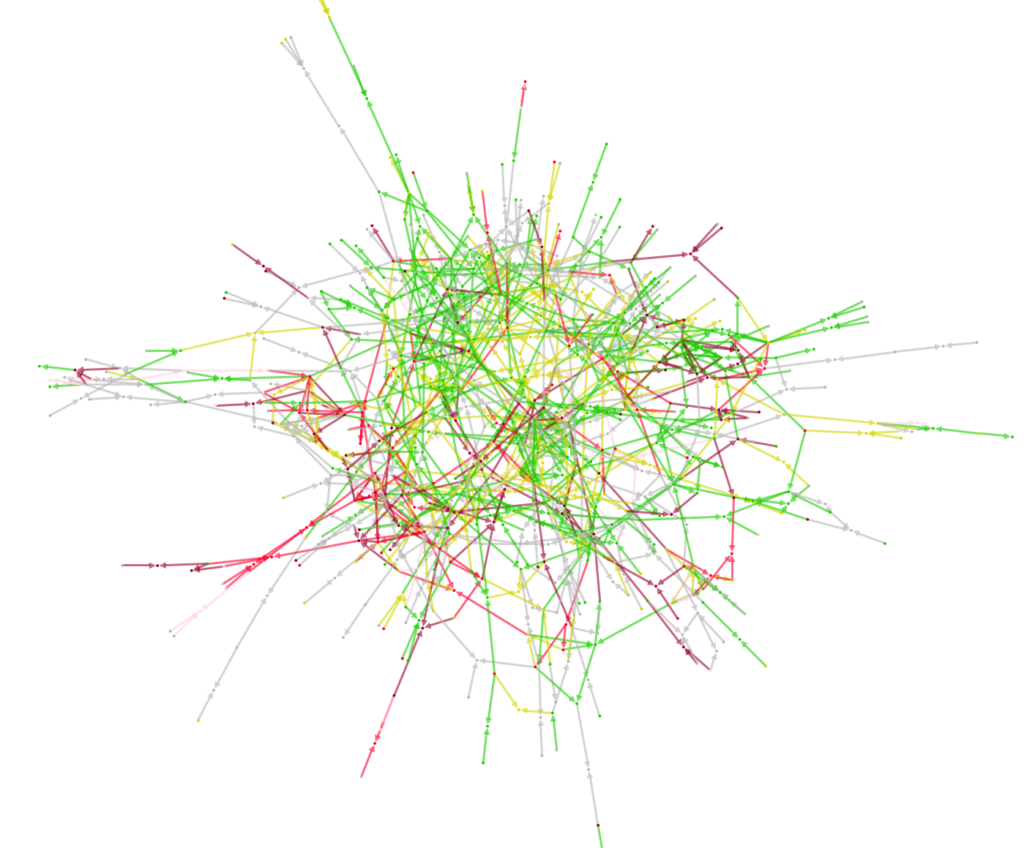

The final example is germ cell data visualization, which is the most challenging as it requires collecting data and often involves interpreting contradictions within the data. In one project, students attempted to understand the patterns of digital trends’ evolution by mapping digital trends over almost four years, resulting in a large visualization. They discovered that stable trends created protective loopholes to ward off new trends that could challenge them. Ultimately, this led to a conservative pattern of repeating the same trends.

Another project involved mapping various initiatives during the pandemic in Brazil. This extensive map displayed the contradictions between problems and solutions found in public discourse. Maria Leticia, a city council member in Curitiba, used this map to identify specific contradictions that mattered to the citizens she represented.

To summarize the presentation, changing what is possible becomes possible when it’s expanded through democratic deliberation, often using germ cells as demonstrated. Expansive designers do not solve problems but help identify and organize collective consciousness to address contradictions.

Regarding the prospects of doing expansive design in the US, where I am moving to now, there is some apprehension due to the cultural emphasis on individualism and personalization. Well, my answer is: should expansive design be already possible there, it wouldn’t be expansive design. Expansive design flourishes amid the tensions between the possible and the impossible. Anyone interested in joining my attempts to make it possible-impossible is invited to collaborate in this research program. Let’s expand the possible!

References

Lorusso, Silvio. (2023). What Design Can’t Do. Set Margins’. https://www.setmargins.press/books/what-design-cant-do/

Simon, H. A. (1969). The Sciences of the Artificial. MIT Press.

Fisher, M. (2009). Capitalist realism: Is there no alternative?. John Hunt Publishing.

Medina, E. (2011). Cybernetic revolutionaries: technology and politics in Allende’s Chile. Mit Press.

Bezold and Hancock. (1993). In: Taket, A., & World Health Organization. (1993). Health futures in support of health for all: report of an international consultation, Geneva, 19-23 July 1993 (No. WHO/HST/93.4. Unpublished). World Health Organization.

Dunne, A., & Raby, F. (2013). Speculative everything: design, fiction, and social dreaming. MIT press.

van Amstel, F. M. C. (2015). Expansive design: designing with contradictions. Doctoral thesis. University of Twente.

Amstel, F. M.C. van; Zerjav, V; Hartmann, T; Dewulf, G.P.M.R; Voort, M.C. van der. 2016. Expensive or expansive? Learning the value of boundary crossing in design projects. Engineering Project Organization Journal, 6 (1), Pages 15-29. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/21573727.2015.1117974

van Amstel, F.M.C; Silveira, G.S; Hartmann, T. (2011) A Problem-Solving Game for Collective Creativity. Annual INSCOPE-Conference, Enschede – Netherlands.

Frediani et al. (2014). Change by Design: Collective imaginations for contested sites in Euston. Architecture Sans Frontières. https://www.asf-uk.org/resources/25-change-by-design-london-2014

Engeström, Y., Nummijoki, J., & Sannino, A. (2012). Embodied germ cell at work: Building an expansive concept of physical mobility in home care. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 19(3), 287-309.

Knetz, Julien (2018). Paris, fenêtres sur l’histoire.

Van Amstel, Frederivan Amstel, F. M. C. (2021). Conservatism in Digital Trends: Findings from a differentialist analysis of influence graphs. InfoDesign – Revista Brasileira De Design Da Informação, 18(2), 37-52. https://doi.org/10.51358/id.v18i2.933

Pelanda, M. F. L., & van Amstel, F. M. C. (2021). A fumaça digital: inversão infraestrutural do COVID-19 pela perspectiva Yanomami (The digital smoke: Infrastructural inversion of COVID-19 from the Yanomami perspective). International Journal of Engineering, Social Justice, and Peace, 8(1), 69-85. https://doi.org/10.24908/ijesjp.v8i1.14735