Visual diary (a.k.a. visual journal) is a method in which a constant, regular, and self-determined creative activity is proposed for the daily life of its bearer. The activity may include recording ideas, creating concepts, taking notes, or playing. The main difference to a personal diary is that here, the owner doesn’t just record what has happened but also what could happen in the future or alternative presents/pasts, mainly through imagination.

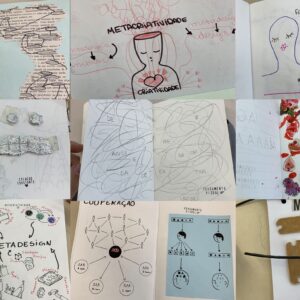

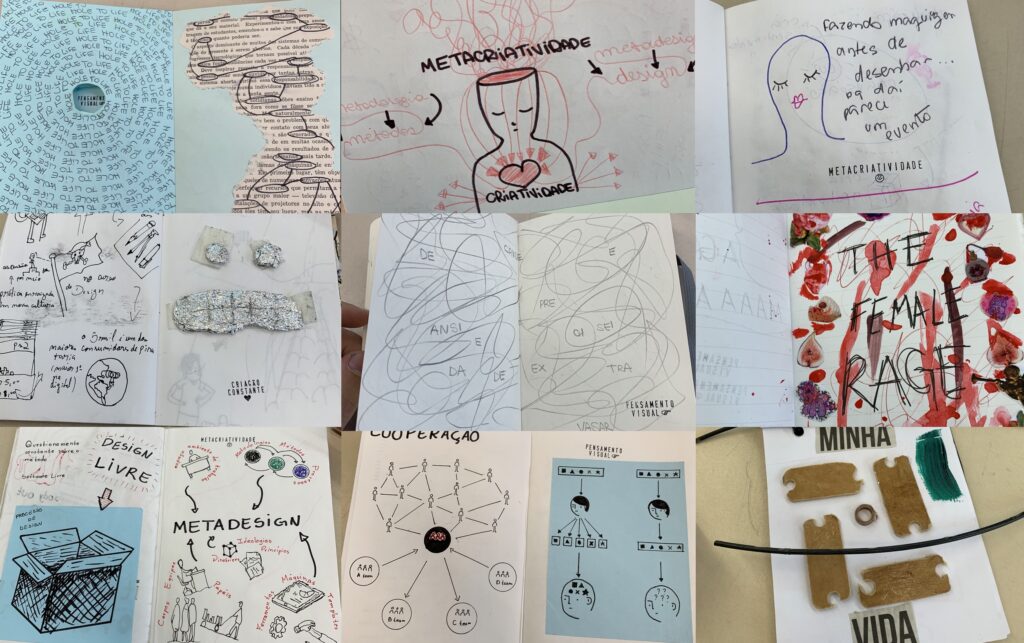

In design research, a visual diary documents a journey through visual thinking, learning how to think visually (in itself), or learning about a new topic visually. The diary may include sketches, diagrams, mind maps, scraps, and other visual methods representing evolving ideas, reflections, and learning processes.

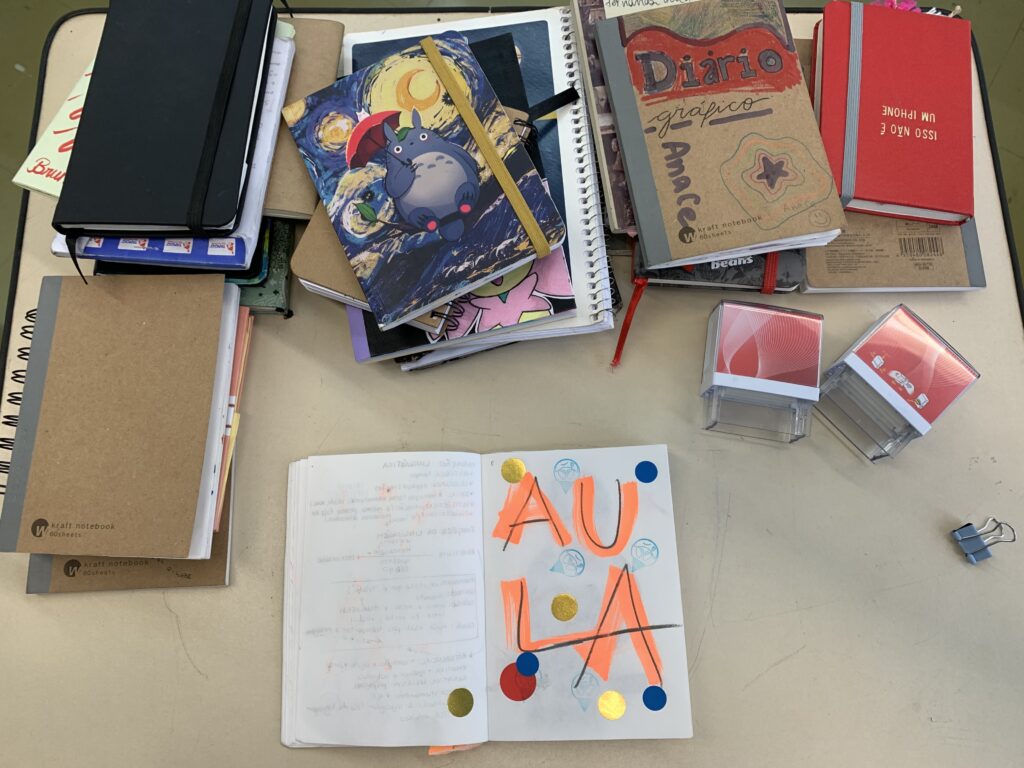

The diary affords diverse media, from sketches and diagrams to mind maps and written reflections. It supports creativity and flexibility, urging design researchers to experiment with different materials, colors, and forms of expression. Even if the notebook could be digital, the analog version is preferred due to its multisensory potential (not just visual but also smells and textures), ease of carrying on without worrying about batteries, and freedom of expression.

The visual diary is more than just a collection of images or sketches; it is a dynamic tool for expanding personal and collective knowledge through visual thinking. It enables design researchers to explore contradictions within the design process, turning these into opportunities for innovation. The diary allows for articulating complex ideas in a non-linear, reflective manner, capturing moments of insight and transformation.

When visual thinking becomes expansive, the diary identifies and visually represents contradictions encountered in the design process. It serves as a space where these contradictions can be explored and re-codified into new insights. To get to that level of depth, the diary must be an integral part of their design research process, not just as a final product but as a living, evolving resource. One particular contradiction stands out in visual diaries: existential crises. By documenting and reflecting on them visually and regularly, design researchers can trace their social origins and envision ways of better dealing with them. In a way, visual diaries can be therapeutic activity for oppressed design researchers.

As a classic design education method, the visual diary can be used to develop and assess students’ ability to reflect on their creative activity, reaching up to the level of meta-creativity: when they are creative about being creative. Beyond the habit of creating things, the student may also reflect on how they are making them. Students can comment and reflect on the collective creativity they got into, for example, in group work, family discussions, work activities, and political decisions by government bodies.

Evaluating visual diaries is a great way to track student development and eventual hindrances in their learning process. Discussing the evaluation with a peer or another teacher is a great way to interpret the results and reconstruct the complex situation of the learner. Evaluation is preferably performed publicly in the studio while students work on an autonomous task. In this way, they can resume their visual thinking exploration as soon as possible.

Required materials

Plain notebook (no lines). Any size will do; however, a 5 x 8.25-inch notebook may fit student pockets and, thus, be carried along for impromptu everyday observations anywhere. A plain notebook is required because a ruled notebook stimulates writing instead of sketching, and the goal here is to combine both text and sketch. A physical pocketbook provides an alter/native moment of interacting with analog devices, which are calmer than the distraction machines of tablets, smartphones, and computers. See the following videos for a more convincing argumentation:

Pencil. Any pencil will do. You may find sketching easier with a thicker tip (0,7 mm for an automatic pencil and H2B for a manual pencil). Consider the pencil’s carry-on features (smaller sizes may fit neatly into your notebook). Do not use pens as they mark the paper too heavily. Sketching requires ambiguous strokes and doodles. When working extra hard on a single theme, you can use pens to trace over the sketch and highlight something you did not capture with the pencil. The opposite is invalid, hence why a pencil is better.

Eraser: never use it in your visual diary, please. It will hamper your creativity. It is not about drawing accurate representations; it is about sketching rough ideas.

Glue stick: to stick printed photos, found product wrappings, used tickets, flowers, or any other kind of designed rubbish/amusement you would like to attach to your visual diary.

Extra materials

Toy or kid’s instant camera with a thermal printer, Bluetooth portable printer, Polaroid Instax, or any other technical means to transform your observations of everyday life without drawing. See the following videos for an idea of how to use the first:

Materials are not as important as fluency in this activity. Make do with what you’ve got and evolve your approach as you go.

Examples

Here is a curated list of Youtube videos and printed books in which people share their visual diaries. Not all of them stick to the definition and practice explained above.

Printed visual diaries

- Iliprandi, Giancarlo. Sketch, Think, Draw. First edition. Milan: Moleskine, 2015. Print.

- Diebenkorn, Richard. The Sketchbooks Revealed. Stanford, CA: Iris & B. Cantor Center for the Visual Arts, 2015. Print.

- Cober, Alan E. The Sketchbook: A Retrospective of People, Places and Things. Neenah, Wisconsin: Neenah Paper, 1981. Print.

- Halprin, Lawrence, and R. Terry Schnadelbach. Notebooks, 1959-1971. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1972. Print.

- Thollander, Earl. Back Roads of Texas. 1st ed. Flagstaff, Ariz: Northland Press, 1980. Print.

- Bergeijk, Herman van, Deborah Hauptmann, and Herman Hertzberger. Notations of Herman Hertzberger. Rotterdam: NAi, 1998. Print.

- Holl, Steven, and Lars Müller. Written in Water. Baden: Lars Müller, 2002. Print.

- Wilkinson, Chris. The Sketchbooks of Chris Wilkinson. London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2015. Print.