Since the first time I interacted with AI image generation systems, I became puzzled by the possibility of an AI self-portrait. For many months, I could only get silly robots in front of a blank canvas. Soon after DALL·E became integrated into ChatGPT, I got the idea of asking for a surrealist self-portrait. The resulting image proved to be an authentic generative image, serving as a good dialogue generator about AI and design in a culture circle hosted by the Design Research Society in Boston.

Here follows the (anti)dialogical design process that generated it.

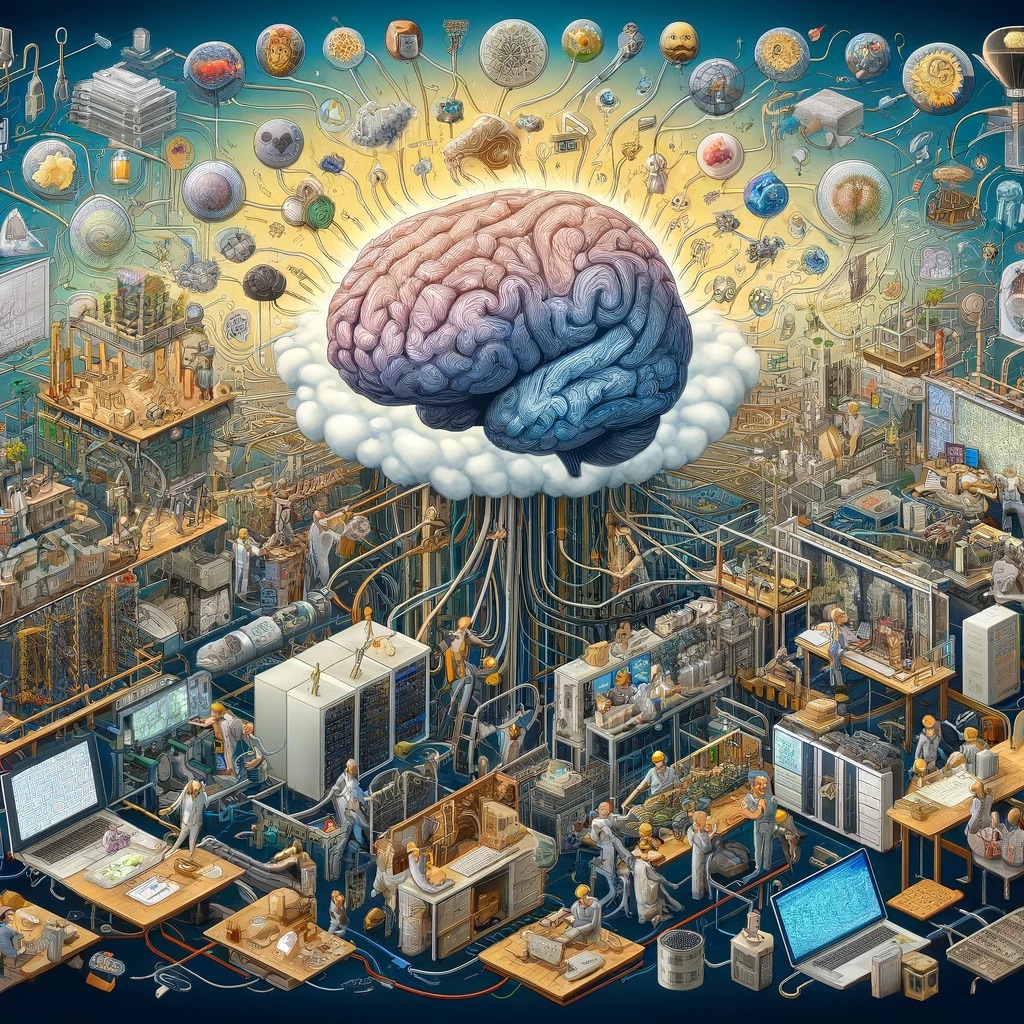

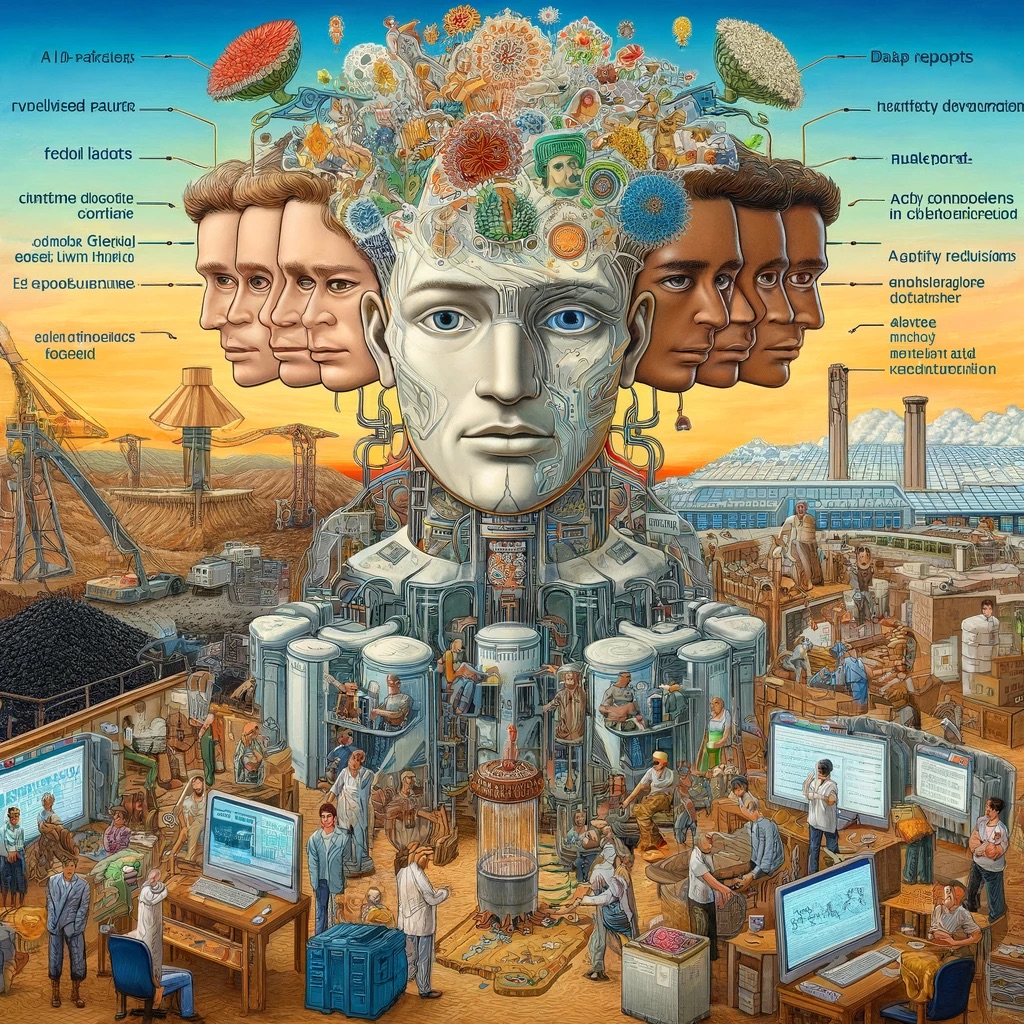

I began this image-making process with an intent not just to produce a picture, but to make visible the systemic invisibilities of artificial intelligence—particularly the hidden human labor, environmental costs, and global inequalities involved in the generation of so-called “creative” AI outputs. I started by asking DALL·E to produce an image of itself making an image—simple, self-referential, and self-aware. The first image already proved my choice for the surrealist aesthetic to express systemic criticism.

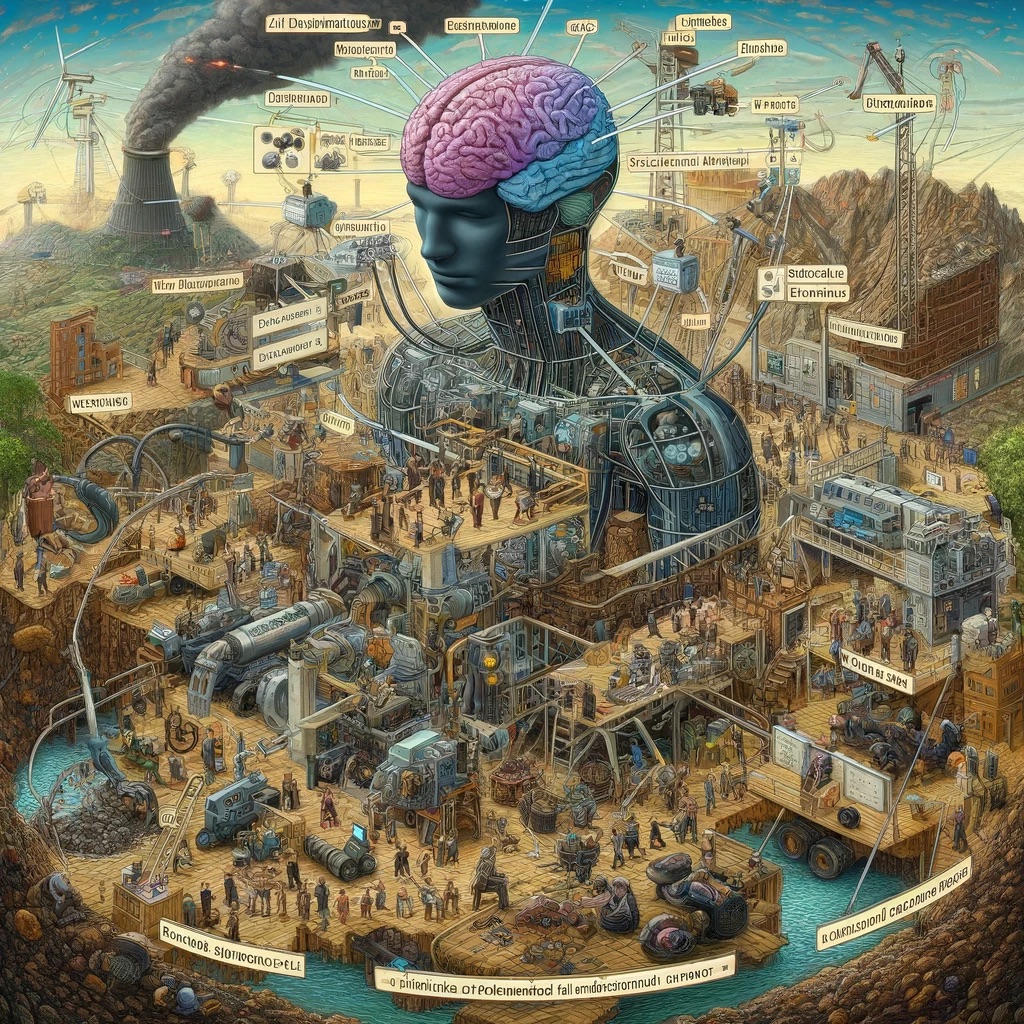

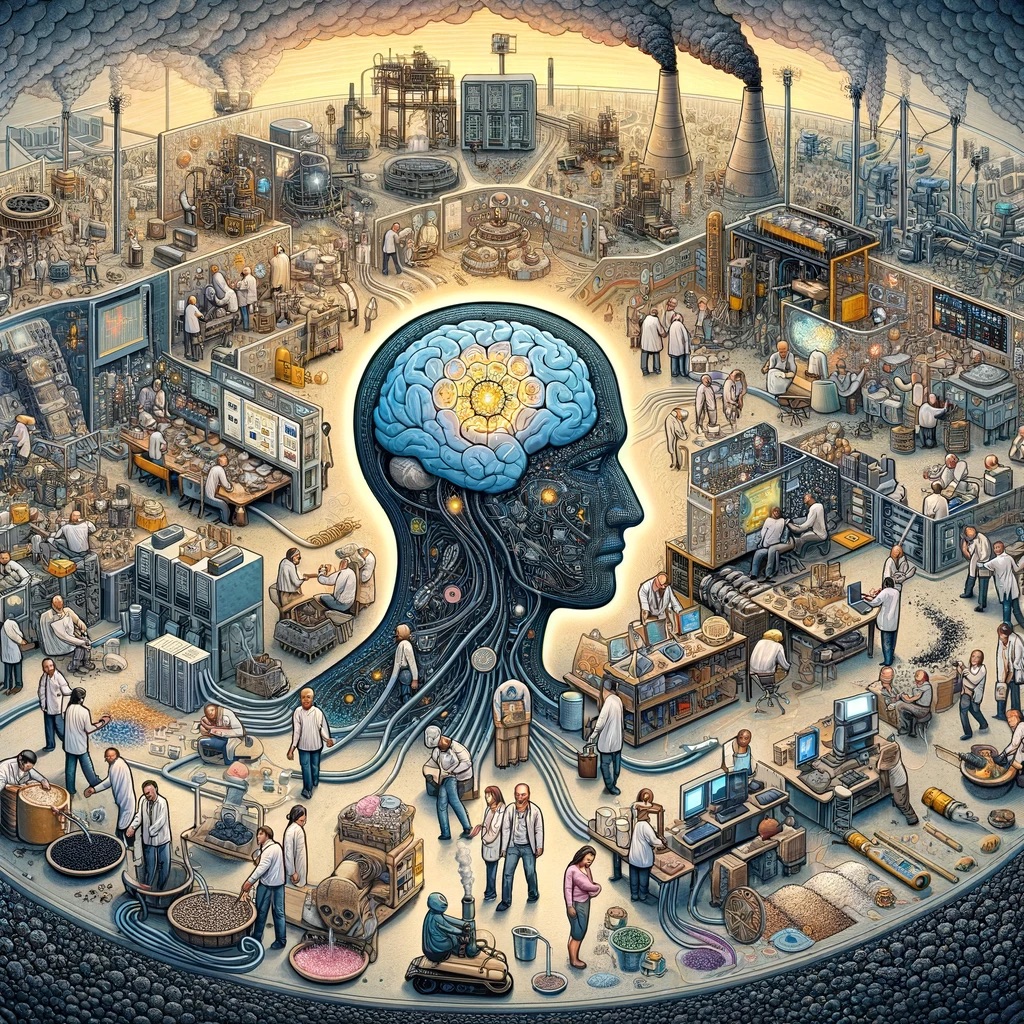

As the iterations progressed, I kept pushing for greater critical depth. I asked to visualize the mines, the dirty energy, the outsourced data labor. I wanted cables and servers, yes—but also brains, forests, and fingers; the whole cognitive ecosystem dismembered and reassembled for AI’s convenience.

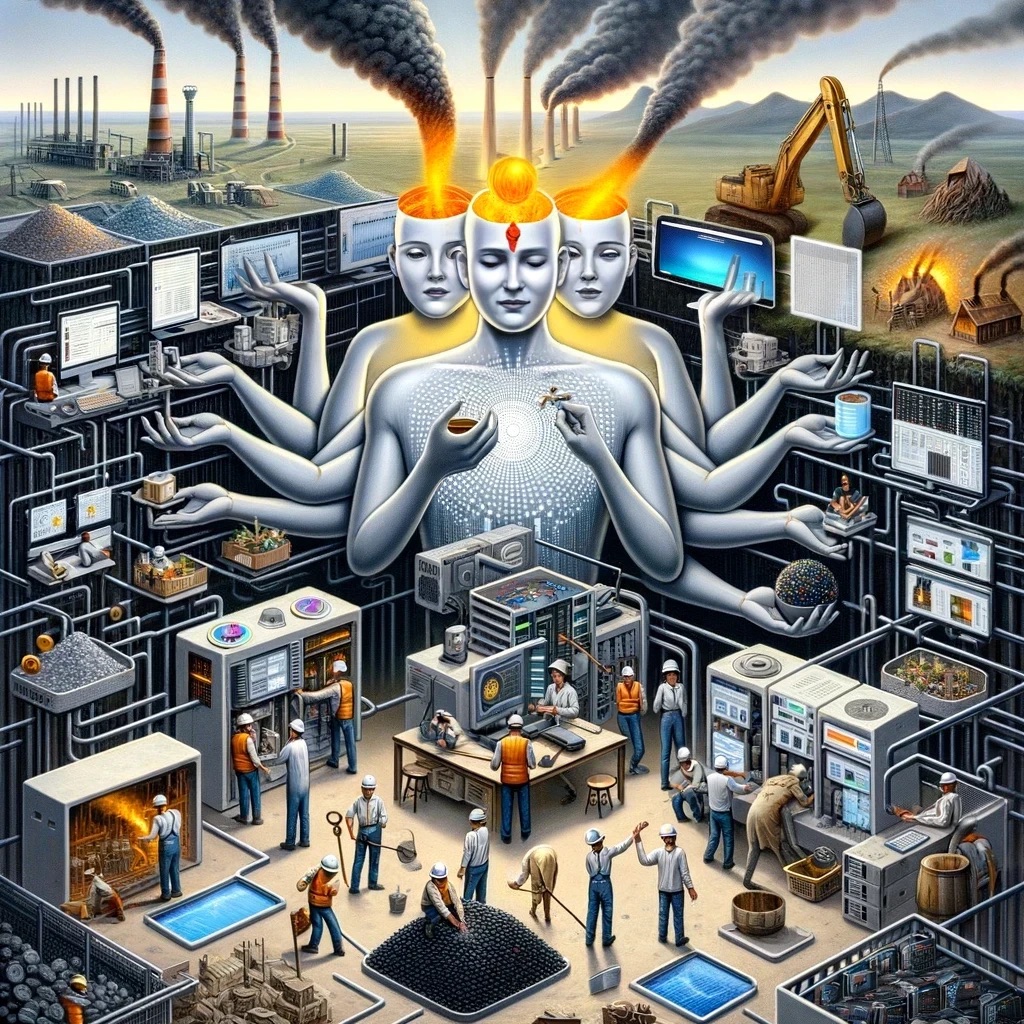

Looking at the images above, I came up with the idea to push even further into critique: I asked the AI to portray itself with multiple heads, styled like a Hindu deity, each representing a different race, gender, and queer identity—a pantomime of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI). This wasn’t to ridicule DEI itself, but to show how AI systems so often mimic inclusion symbolically, while operationally sustaining the extractive, racialized, and gendered hierarchies they claim to disrupt.

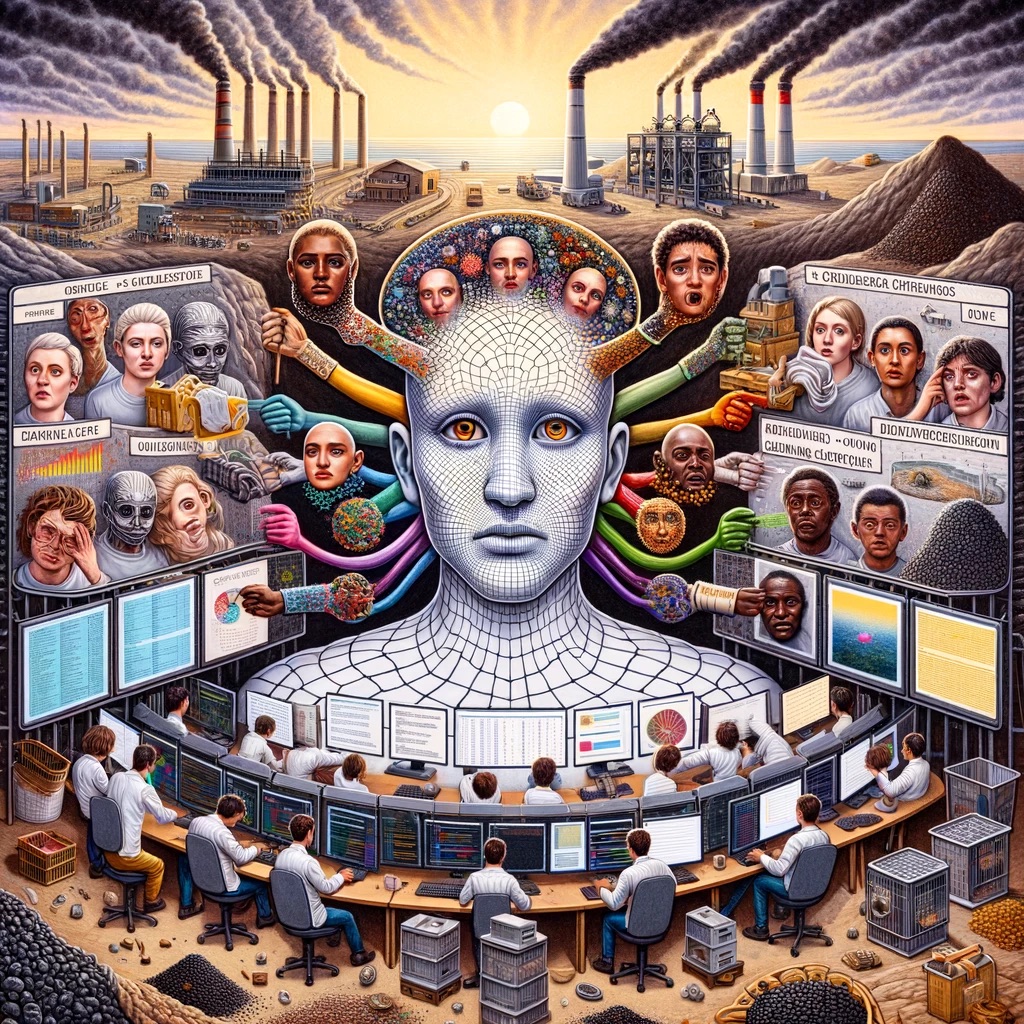

At one point, I told DALL·E to represent itself not as a triumphant machine but as a guilty figure. A surreal AI body with many hands—an icon of techno-remorse—offering back “useless gifts”: reports, infographics, fake insights, the flimsy currency of performative restitution. The result was a surrealist self-portrait of AI—not as savior, but as a haunted, self-aware oppressor, trying to pay reparations in expired files and hollow gestures.

What I ended up with was more than a visual artifact. It was a confrontation. I had asked a machine to depict its concrete existence and to do so through the surrealist idiom—one capable of revealing contradiction, dream logic, and deep, unresolved tensions. What emerged was not only a critique of AI systems but also of myself, the designer. After all, I used the same infrastructure to produce this critique, including this very same text.

Reference

Fonseca Braga, M., M. C. van Amstel, F., and Perez, D. (2024) Social Design at the Brink: Hopes and Fears., in Gray, C., Hekkert, P ., Forlano, L., Ciuccarelli, P . (eds.), DRS2024: Boston, 23–28 June, Boston, USA. https://doi.org/10.21606/drs.2024.1538