Abstract: Oppression is not an isolated phenomenon that involves two persons: the oppressor and the oppressed. Oppression is a systemic contradiction that affects many persons, spreading through cascading effects and twisted positionalities. One oppression relation can affect another, generating the possibility for the same person to be both an oppressor and an oppressed in different relations. This presentation examines cascading oppression in and through design, drawing inspiration from Theater of the Oppressed practice.

This presentation was a guest lecture hosted by Deǧer Özkaramanlı in the ID5541 – Workshop / Design Competitions: Climate Action in Kenya, TUDelft, 2023. A Hybrid Image Theater workshop followed it.

Video

Audio

Full transcript

This is a short presentation on trying to grasp how oppression reproduces itself through multiple and different relationships. How one person oppresses another person who’s also oppressing a third person and so on and so forth. Let’s begin with the definition of what oppression is, at least in this presentation. I’m going stick to the definition devised by Frantz Fanon, Álvaro Viera Pinto, Paulo Freire, Augusto Boal, and other Latin American and Caribbean authors who have considered oppression as an ontological phenomenon.

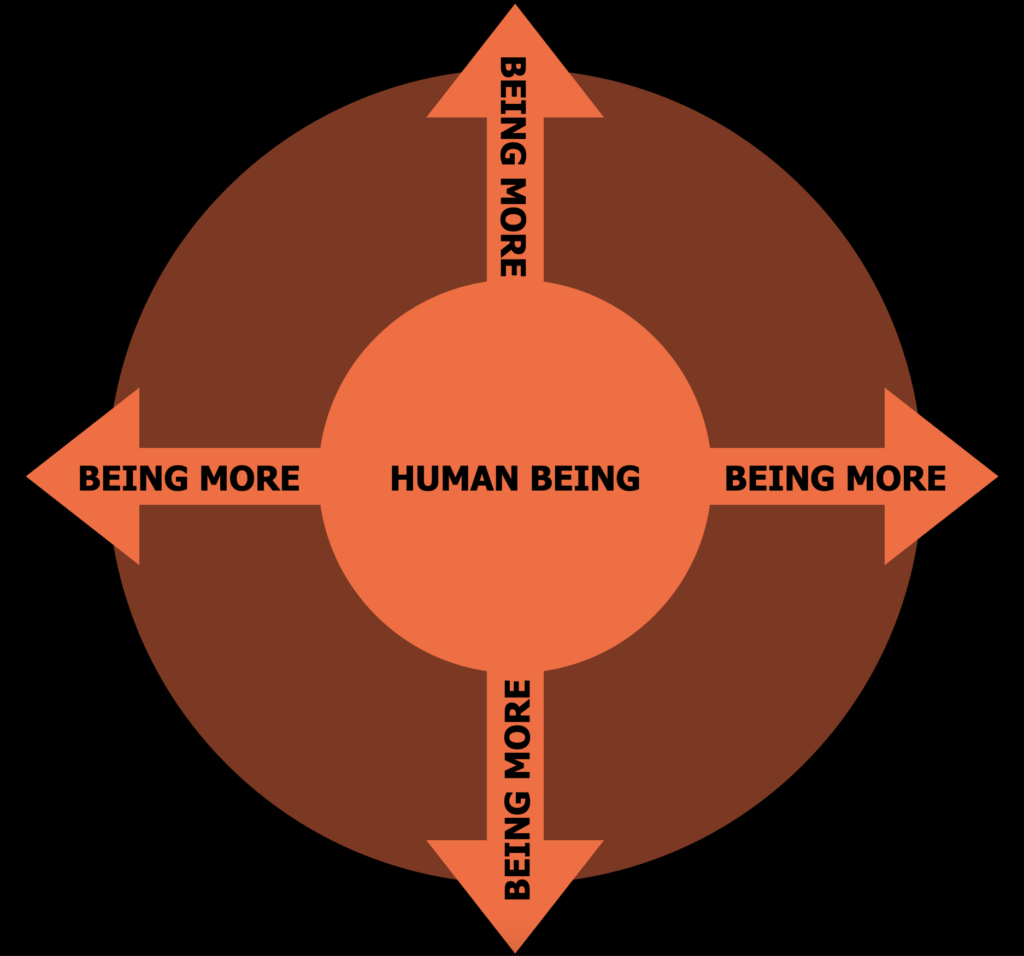

Oppression is a situation where a human being is prevented from realizing its ontological vocation of becoming more, in the words of Paulo Freire. He said that human beings are unfinished beings and they are always seeking to add new features and develop new capabilities, effectively expanding outwards and changing the surrounding world.

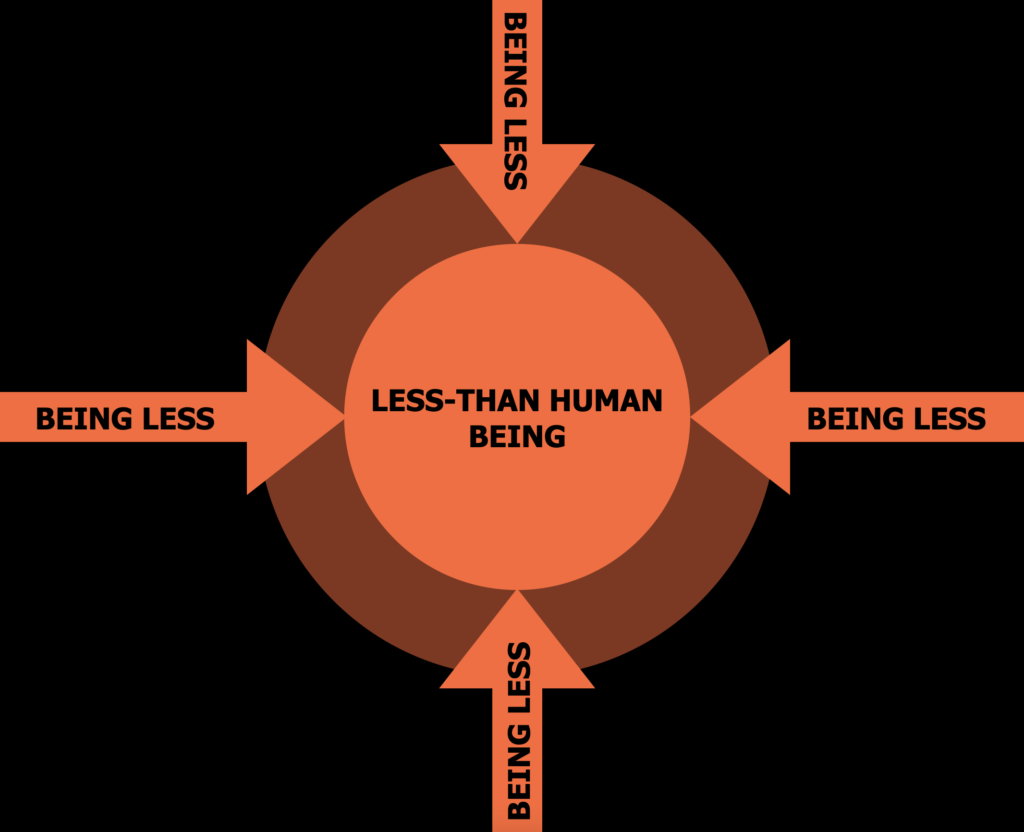

However, due to specific historical circumstances, especially in divided societies where human beings are grouped in social groups and in social groups they receive a specific social status. Sometimes even a social status of not being human or being less than human. In this situation, this so-called oppressed social group is prevented from developing all the full human potential that it has. There are forces pushing less than human beings to being less than what they could have been if they hadn’t been oppressed.

Let’s get an example of how this unfolds on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post magazine published for a long time in the United States. Richard Sargent has depicted this anger transfer mechanism in his cover illustration (1954). The boss is yelling at the employee, the employee comes home, the employee is yelling at his wife and the wife later on is yelling at the child, a poor child who can only yell at his cat.

This is a funny depiction of oppression relations and how oppression spreads through different people but it is very simplistic. We have to develop a little bit further especially because oppression is not just about anger. There are many other ways you can reiterate the oppressive structure. The main one might be humiliating, putting someone else into the situation of feeling that they are incapable of doing something or they are naturally inferior. For example, they have a disabled body or they have an under-aged body or they are lacking something. This picture does not depict that but it helps us to grasp how this oppression unfolds through the multiple relation.

If we try to theorize this picture, we might be tempted to find out that oppression is a kind of closed loop where the oppressor oppresses the oppressed and so on until the oppressed oppresses the oppressor. That would justify oppression in the way any oppressor would feel like they are doing something right because they are just reproducing what they already have. In this funny addition to the original illustration, internet meme enthusiasts have put the cat hitting the big boss, but of course, this is just a joke. The cat is not conscious of being oppressed. Cats do not have the same kind of subjectivity human beings have. Cats are not even supposed to think that they are more or less than humans because they only have a conception of being a cat.

The point here is that oppression is not a closed loop like natural predation, so it’s not the same as the strongest trying to dominate the weakest or doing that in an automatic way. We always have a choice either to oppress or not, at least in this oppression theory that I’m presenting here. For example, coming back to the painting, the poor child that has been oppressed at the end of the oppression chain will grow up and, at some point in his life, he may become a new boss or new employee and choose not to oppress other people. That’s up to the child to decide, and also it’s up to the context and the structures that the child will live around.

There’s always an opportunity for the oppressed to avoid reproducing the same kind of oppression experienced in the past. That’s why oppression is more like a human phenomenon and not necessarily an animal phenomenon. Some people think that there is no oppression towards animals because that’s really about human social interaction. Other people might say even if they don’t have the same kind of consciousness, they are still being subjected to violence. I don’t want to go deep into the discussion of whether cats and animals can be oppressed, I just want to point out that there’s always the possibility of overcoming oppression.

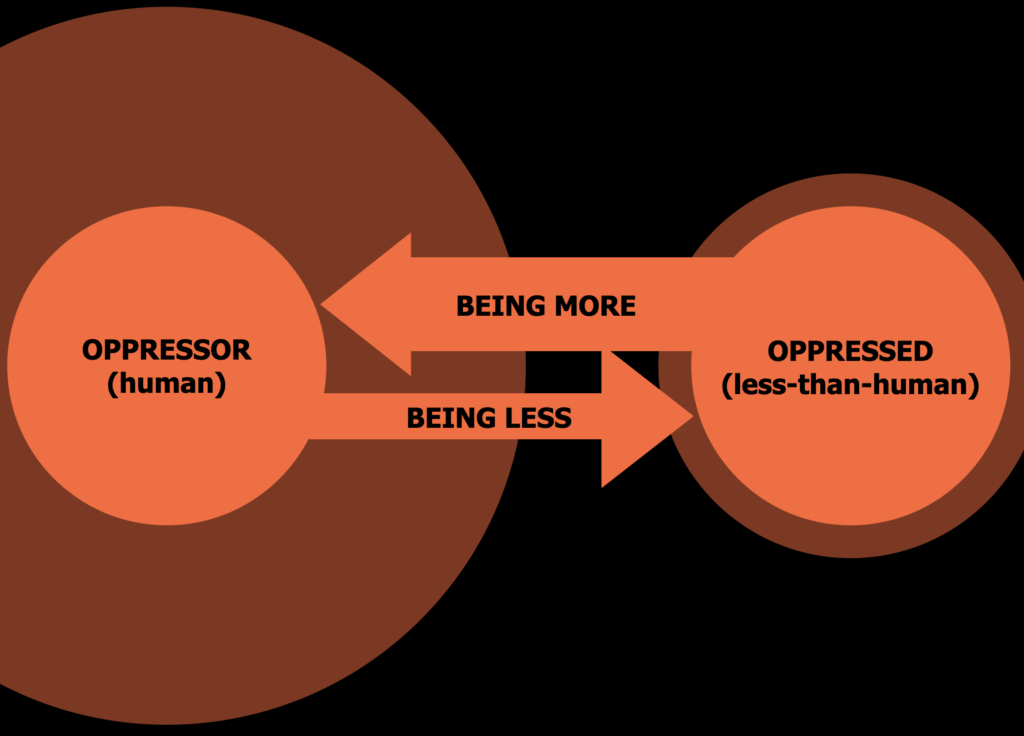

Let’s take a look at how this oppressor-oppressed interaction unfolds in that relationship. Coming back to the definition of oppression as curtailing the ontological vocation of being more and then receiving, in turn, the being less force. Here you see what happens across human history if oppression is a constant force of being less directed towards the oppressed and also an exploitation of the being more potential of the oppressed towards the oppressor. The result is that oppressors get to humanize, to become more than the oppressed so they have a larger reach of action, and more possibilities of doing things than what they already have done in the past before interacting with the oppressed.

How does this all relate to design? Well, while looking at the history of the concept of users and how designers treat users in human-computer interaction, I have found, together with my colleague Rodrigo Gonzato, that designers are indeed on the side of the oppressors while users are on the side of the oppressed. We have found much evidence, for example, of describing users as stupid people who don’t want to think about how to use computers or people who don’t have certain skills. This prejudice undermines the possibility of developing further and becoming more than what the users are expected to be while interacting with computers. That’s why we describe this situation as the user oppression.

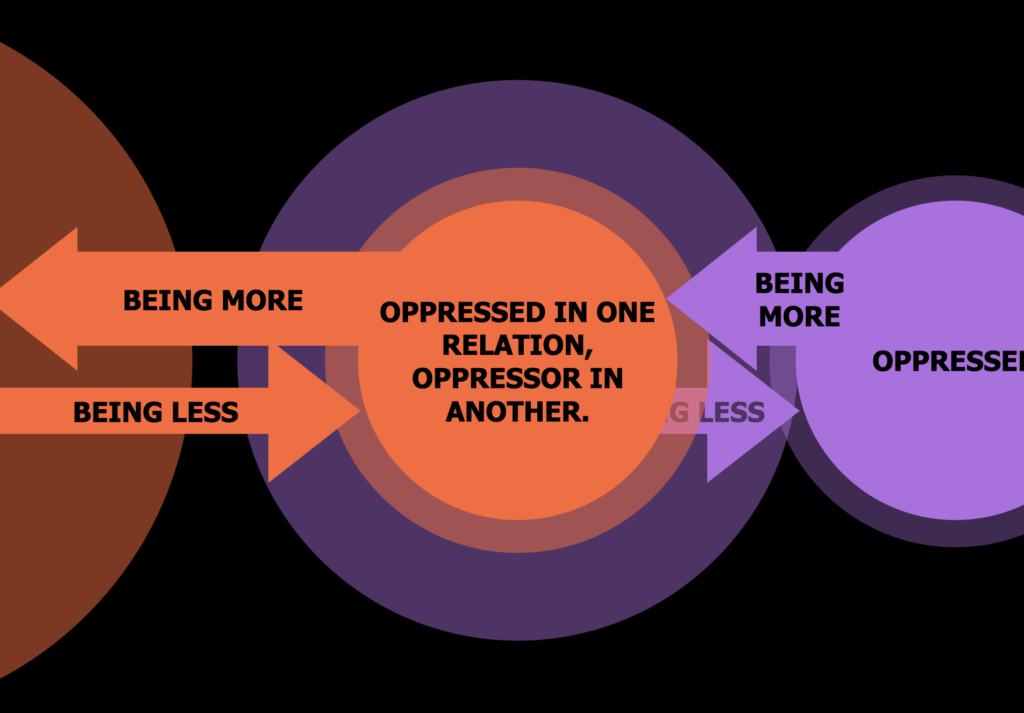

After publishing this research, we became curious about situations where designers are also oppressed, and we had to devise, and we are still not done with that, a concept for dealing with a situation where the same person is oppressed in one relation and oppressor in another. That, of course, is similar to what we have seen before in the anger transfer picture because well if we can grasp this double-sided or this contradictory positionality of being both an oppressor and an oppressed, we can perhaps target multiple oppression in the same design project, design intervention, or design research or even design philosophy.

For instance, a lot of design research has focused on one of these oppression relations. There are already some anti-racist and anti-misogynist, sometimes even anti-ageism or anti-ableism, but trying to grasp all of these oppression relations and be anti-oppressive in general enables the possibility of designing insurgent coalitions of the oppressed. Forming larger groups can perhaps be more effective to fight oppression and that’s why we are seeking this more systemic understanding of oppression.

Coming back to Richard Sargent’s painting, we already see that we can explain this anger transfer through oppression theory. In the first corner of the image, we see the boss representing capitalists oppressing the workers or the proletariat, and in the second one, we see the man yelling and abusing the woman in a gender relation. The woman, by the same token, would oppress her child in the age relation and, in the fourth corner, it’s the most controversial: the child oppressing the animal. As already said, for some scholars, this is not considered oppression because animals like cats cannot have this intersubjective relationship of being more and being less that we have seen before, therefore they are not oppressed even if they are surely subjected to violence that should be avoided.

If we turn this back to the design field and what design can do about it how does cascading oppression unfolds in the design field? We are developing this understanding to expand the current scope of design research further from the user-worker interaction. Users are an object of concern for designers and sometimes designers oppress users, but most designers are trying to prevent users from oppressing workers and having a better dialogue with them, especially in the case of service design. The other way is also a possible concern for designers, where workers oppress users.

There is a lot of talk and a lot of tools and methods to devise and understand this front-stage/backstage interaction. Design often draws from theater to figure out this relationship between a public place where an activity is held and a private space where the activity is prepared. Methods like custom journey mapping, service design blueprint, and others try to figure out this user-worker interaction or customer-employee. Designers develop ethical principles for their relationships, such as having a good user experience or having a good employee experience.

What we get if we bring oppression to the table is that the subject who is looking at the object is also part of the oppression relations. Oppression as I said, is an intersubjective phenomenon, hence designers should be implied and mapped into the oppression relations. We have already done quite some research in showing how designers oppress users across the so-called frontstage and in what we are now calling the belowstage to extend further the theater metaphor.

Nevertheless, designers are also oppressed in a different relation. In capitalist work exploitation, designers are the oppressed workers whereas the capitalists are the oppressors, located in the abovestage, pretty far away from regular visibility. They can still be criticized and visualized by design research, though. Why not do design research to make capitalists visible and not just workers? In this way, we can perhaps address the structural feature of oppression.

We are trying to expand the understanding of oppression from the user-worker interaction towards design-users interaction, and designers-capitalist interaction. There are other kinds of oppression relations that we haven’t focused on here, for example, we could put White people at the abovestage, where white supremacists like to stay, but right now I’m just focusing on the specific features of cascading oppression in capitalist design.

Right now, there is ample research available to demonstrate how capitalism is enmeshed in design. Well, there is also plenty of research on how racism is integral to design. Here’s an example of how racism is embedded into graphic design. These are some examples of assorted racist products that were being sold in United States supermarkets just some years ago.

George Floyd’s terrible murder raised a lot of public attention on racism in society, and these products were taken off the shelf because they had this racist depiction of old fantastic times when Black people lived their lives to serve White people, for instance, by preparing them great food. Racist products also misrepresent indigenous people as if they were part of the natural resource brought to the consumer. The product imagery equates indigenous people with natural resources to be consumed similarly. Furthermore, it misrepresented the Inuit as Eskimos, which is not how they self-identify.

These are just some examples of how designers oppress users, but you’re probably thinking that designers cannot stop doing this unless the capitalist tells them to do so. That’s right, and they also cannot stop doing that if users demand racist or oppressive services. Here is a service design example where a White woman user oppresses a Black man worker because he delivered her food too late, at least from her perspective, so it was cold. She then considered reenacting this despicable racist ritual of slavery times of weeping the Black man. The public attorney prosecuted her, yet the company did nothing to prevent this racialized interaction from occurring again. Couriers working for these digital platforms must organize protests themselves against racist users. The company could have done much more, but the problem is that capitalists don’t find they can profit from this.

Capitalists typically seek the most effective methods to derive profit from their employees. If these profit margins aren’t met, they often result in employees being let go. Now, envision a speculative design scenario where a work management tool offers data, some of which might be questionable, to assist managers in making layoff decisions. Within this hypothetical, even designers aren’t safe from job cuts, as illustrated by a recent significant layoff event.

Capitalists are usually interested in finding the best way of profiting from workers. If they cannot profit enough, they fire the workers. In this speculative design example, a designer is trying to imagine how Workday, a standard work management platform, may provide some sound information or even some information managers shouldn’t provide to decide who will be laid off and how much they could save. Designers include themselves in the oppression because they would probably be fired too.

These narratives highlight the intricate layers of oppression present in our society. Addressing these forms of oppression isn’t straightforward; it isn’t merely about turning complicated challenges into simpler ones. If we were to eradicate oppression completely, our societal foundations, deeply rooted in such dynamics, might be jeopardized. Consider this: What would capitalism look like without the exploitation of workers?

Some societies, such as indigenous communities, may not face these exact forms of oppression. They might operate outside capitalist structures yet have distinct forms of discrimination that we don’t have. Still, it’s crucial to understand that no society has entirely eradicated oppression, making it a continuous endeavor throughout human history.

The realm of design offers a unique perspective in understanding and mitigating oppression. It acts as a nexus between art, engineering, and science. A valuable exploration in this context has been Theater of the Oppressed, which views oppression as embodied within societal constructs. Through design, there’s potential to redirect oppressive structures towards means of liberation.

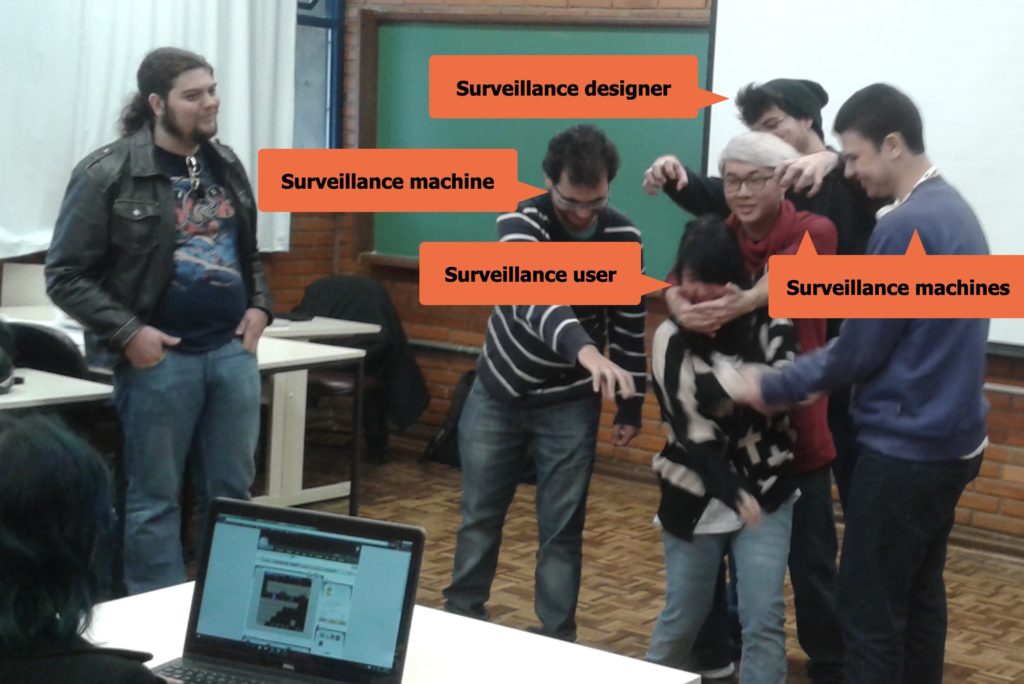

A specific technique under the theater of the oppressed is Image Theater. Hailing from Peru, it was initially used to illustrate oppression to those who couldn’t read, inspiring them to learn and subsequently challenge their oppressive circumstances. Image theater relies on static body representations to communicate potent messages. It has been incorporated into design education to increase designers’ awareness of oppressive dynamics. For instance, I used Image Theater to delve into surveillance technology. Students found out gradually that the user was not the only one to be oppressed in such interactions.

This method has also evolved for remote environments, especially during pandemic times, where 3D modeling tools and digital platforms replicate the traditional format. These sessions frequently culminate in rich discussions dissecting various aspects of oppression. Image theater’s potency lies in its ability to represent reactions to oppression, creating a visual narrative of liberation possibilities through physical gestures, rituals, and expressions. It underscores the importance of actively positioning oneself against prevalent oppressive norms.

To wrap up, even though our focus might be on specific instances of oppression, it’s a stepping stone towards broader societal transformations. There’s the potential to inform public policies, formulate laws, and even guide product designs in a way that discourages oppressive actions. These have to consider cascading oppression so that oppression in one relation does not “spill over” to another relation. Design inspired by Theater of the Oppressed seems fit for developing the critical body consciousness required for such a job.

References

Gonzatto, R.F. and Van Amstel, F.M.C. (2022), “User oppression in human-computer interaction: a dialectical-existential perspective”, Aslib Journal of Information Management, Vol. 74 No. 5, pp. 758-781. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-08-2021-0233

Serpa, B.O., van Amstel, F.M., Mazzarotto, M., Carvalho, R.A., Gonzatto, R.F., Batista e Silva, S., and da Silva Menezes, Y. (2022) Weaving design as a practice of freedom: Critical pedagogy in an insurgent network, in Lockton, D., Lenzi, S., Hekkert, P., Oak, A., Sádaba, J., Lloyd, P. (eds.), DRS2022: Bilbao, 25 June – 3 July, Bilbao, Spain. https://doi.org/10.21606/drs.2022.707

Gonzatto, R. F., & van Amstel, F. M. (2017, October). Designing oppressive and libertarian interactions with the conscious body. In Proceedings of the XVI Brazilian Symposium on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1-10). ACM, New York, NY, USA, Article 22, 10 pages. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3160504.3160542