Abstract: This talk introduces the activity of Design & Oppression, woven by design professors, students, and professionals from all over Brazil from the perspective of one of its cofounders. The network discussed and experimented with several ways of recognizing how design reproduces oppression in our society. As of late 2021, the network is interested in design by the oppressed for the oppressed with eventual allies, against all forms of oppression.

This talk was delivered at the Critical Design Roundtable hosted by the StudioLab at Cornell University, next to Pluriversal Design SIG and Design Justice Network talks.

Audio

Video

Full transcript

Thank you very much, Wes and Renata, for your presentations. I’m going to speak on behalf of the Design and Oppression Network, and we are very grateful to meet you because you have been an inspiration for our network here in Brazil. You might not have known, but we have been following the Design Justice Network and the Pluriversal Design SIG steps closely and trying to build something relevant to our conditions in the geographic Global South.

The interesting thing about the Global South is not so much its geographical location but rather the movement of globalizing different geographic locations—especially globalizing those groups that have been denied their ways of globalizing and meeting each other. I would like to thank John for supporting the globalization of the South with this historical meeting today, right? This is the first time all three of us are meeting, and I’m really happy to be here.

I don’t have a land acknowledgment discourse because we don’t typically do that here in Brazil. We never had settler colonialism in Brazil; only exploitative colonialism. Land is still being disputed, and there is a major trial currently taking place in the Brazilian justice system called the “Time Limit Trick.” If it passes, this dispute will be effectively shut down, and Indigenous people will no longer be able to reclaim land they haven’t previously claimed. That is the most important thing to say about land now—it is central to the history of Brazil. I speak from Curitiba, an Indigenous name derived from the juxtaposition of “a lot of pine trees,” which has no longer a material basis. The pine trees are mostly gone.

The issue of land in this country is far from being settled according to Indigenous peoples. Yet, Indigenous people are not the only ones oppressed, and the concept of social justice is not as widespread or socially accepted in a way we could appeal to in a rational way. If we talk about justice in general, people accept it as reasonable. But if we speak about oppression, people become more interested because that frames reality in a counter-hegemonic way.

I’m going to talk a little bit about designing against oppression. This is a personal reflection on what I have experienced collectively in this network. In general, I can only speak for myself, but if my collective, is present, I can speak on their behalf. I want to acknowledge my colleagues Bibiana, Samya, Eduardo, Desiree, and Rodrigo who are also online here now. If I say anything you do not agree with, please type it in the chat so we can truly reflect on a collective perspective in this short talk.

First of all, why do we focus on oppression? Because it is a major issue discussed in the public sphere in Brazil. For example, there are public demonstrations on the streets where people claim that oppression does not exist. In 2019, there was a peak of demonstrations against Paulo Freire, against the so-called “hysteria of oppression,” and against public universities that endorse his theories. This was part of a long process of growing right-wing politics.

Why do they criticize Paulo Freire? Because his books have been widely read and discussed in public universities. Even though he is no longer alive, his ideas live on through his books. Paulo Freire, to summarize, does not describe oppression as something immutable or unchangeable; rather, he presents it as something that can be overcome. This is why his work is so dangerous to right-wing politics—it opens up possibilities for resistance, to conscientization, which is the historical understanding of how oppressions came to be.

Freire does not describe just one type of oppression. Although he was primarily concerned with the oppression of peasants, his framework applies to many kinds of oppression—for example, gender oppression, racial oppression, and Indigenous oppression.

Until 2020, we organized protests in universities against the far-right anti-science policies, but with the pandemic, we could no longer organize street protests in a meaningful, collective way. The pandemic severely affected us politically, and that prompted us to organize online. This led to the co-founding of the Design and Oppression Network, which brought together people from different universities in Brazil who were trying to find alternative ways of protesting. We met online and began organizing sessions. This brief history of the Design and Oppression Network is written in a paper that will soon be published in the PIVOT 2021 proceedings. I will summarize some parts of our story.

First, we started an open weekly reading group on Discord. We had to use Discord instead of Zoom because many people in Brazil do not have access to high-bandwidth internet and cannot use webcams. Discord works well for audio connections and requires lower bandwidth, making it more inclusive for people in different regions of Brazil.

We currently have more than 500 members spread throughout the country. We chat, discuss in these reading groups, and initiate other actions, such as synthesizing what we have learned by revisiting the works of Paulo Freire, Frantz Fanon, Augusto Boal, bell hooks, and other authors who have theorized oppression.

We produced live-stream videos that became quite popular, discussing the relevance of these authors to design. The question we explored was: What do these authors have to do with design? Are they relevant to design? And, of course, the answer we gave was yes. But why? Because design, as it is practiced, often plays a role in oppression. However, we needed to understand how this oppression was concretely reproduced in everyday life.

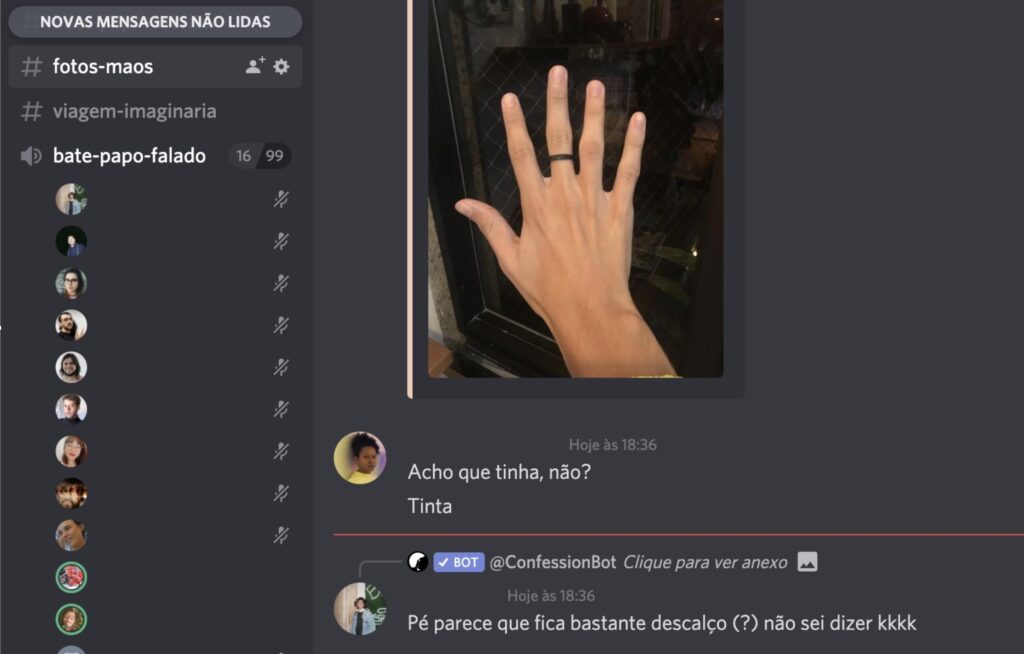

At some point, we began experimenting with Augusto Boal’s Theatre of the Oppressed dramatic games. Since these techniques were originally developed for face-to-face interaction, we had to adapt them to an online setting using various tools available on Discord. For example, we experimented with sharing pictures anonymously—such as images of hands—and then guessing whose hand it was. This activity sparked discussions about privilege and lack of privilege. Was a particular hand shaped by the kind of work that person does? Or was it shaped by other influences, such as gender aesthetics? This exercise helped us explore how oppression becomes embodied—how it manifests in our bodies and the way we present ourselves to others.

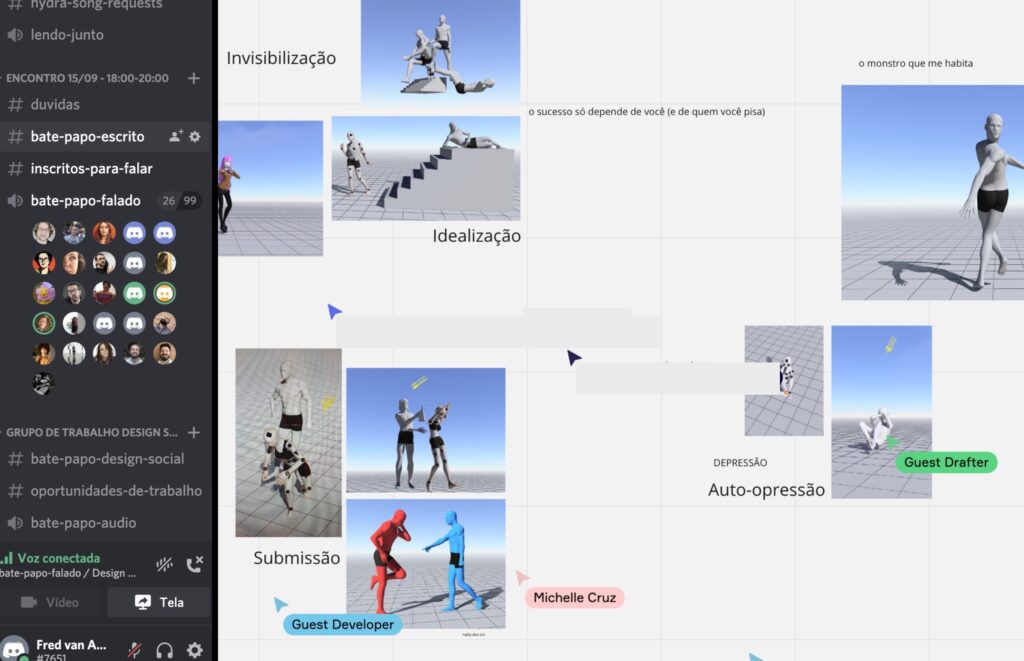

We also experimented with Image Theatre, another technique from Theatre of the Oppressed. How do you perform Image Theatre, which is so physical, in an online environment? We improvised. It wasn’t ideal, but we did our best. We used 3D modeling tools like Magic Poser and digital drawing tools to create quick scenes, which we shared on a whiteboard. This allowed us to discuss how oppression is embedded not only in bodily shapes but also in postures. For example, someone standing hunched over, looking downward, might unconsciously be expressing oppression through their body posture.

At another moment, we delved into understanding ourselves as oppressors and explored how oppressive figures influence our thoughts. We used the Rainbow of Desire, another Theatre of the Oppressed technique, which was a truly eye-opening experience. One exercise involved externalizing the “cops in our heads”—those internalized voices of authority that hold us back. One person would metaphorically remove the “cop” from their head, and another would play the role of that cop, engaging in conversation. Through these dialogues, we confronted those internalized oppressions, learning how to recognize and resist them so they wouldn’t dictate our actions.

We also extended our Theatre of the Oppressed experiences to a wider audience, particularly through a format well-suited for YouTube streaming. In one performance, we explored the impact of platform work on design labor, emphasizing how designers are implicated in these exploitative systems. Designers create the interfaces that obscure the extreme exploitation behind platform labor, sometimes even designing mechanisms that make exploited workers believe they are independent entrepreneurs rather than being exploited. We acted out these dynamics using our bodies while enhancing our expressions through virtual costumes and augmented reality effects.

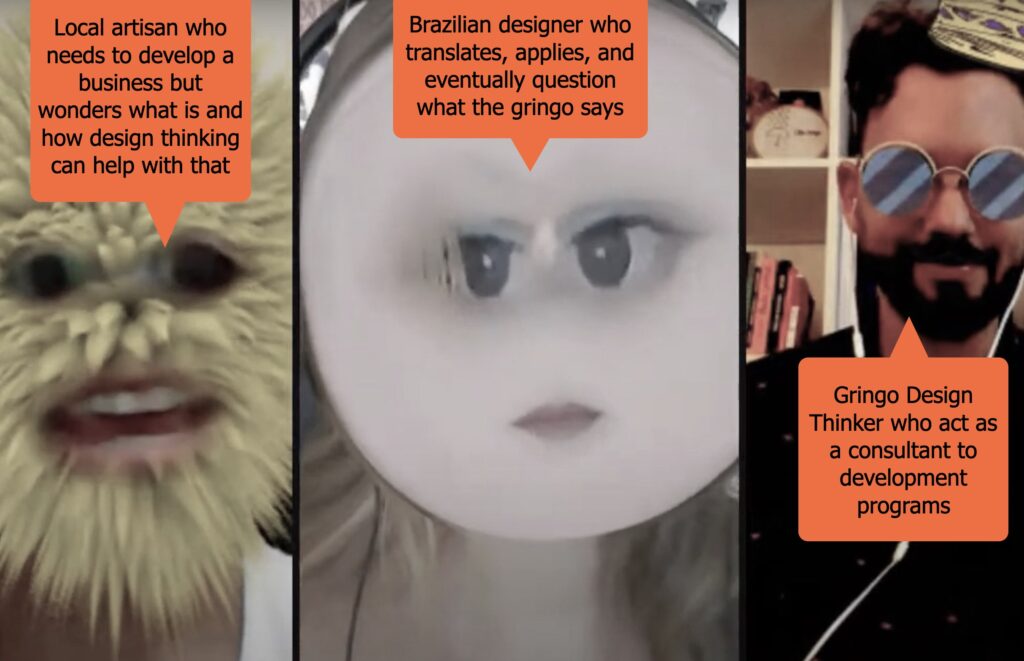

Another key area of exploration was methodological colonialism, particularly with the design thinking method promoted by Stanford University and IDEO. These frameworks have become highly influential in Brazil but in a deeply problematic, one-directional way. We are expected to adopt them unquestioningly as if they were universal truths, rather than engaging in a reciprocal exchange of knowledge. Many consultants push design thinking as a ready-made product, selling it to Brazilian companies and international development programs without acknowledging the existing knowledge and practices of local artisans and communities.

Through our theatre rehearsals, we enacted scenarios that illustrated this dynamic. Though not based on a single specific case, our performances resonated with audiences, helping them recognize their own experiences of methodological colonialism. For instance, we explored how Brazilian artisans were often made to disregard their traditional knowledge and practices as if they lacked “design thinking” entirely—reducing their expertise to mere “design doing.” This is a clear form of colonialism, as it erases local knowledge systems in favor of a Western-imposed methodology.

These moments of conscientization—of collectively building awareness about oppression—were truly powerful. Our discussions and performances reached not only people in Brazil but also Latin American audiences more broadly. While Spanish speakers could engage with our work due to linguistic similarities with Portuguese, we struggled to include participants from other regions, particularly English speakers.

To address this, we organized the Designs of the Oppressed online international course in English, bringing together participants from around the world to share their experiences of oppression and experiment with our methods. The course was fully recorded and is available online as an open educational resource, allowing others to engage with our discussions and exercises. While it’s not the same as participating live, we plan to offer similar programs in the future, potentially in other languages as well.

One of the highlights of the Designers Oppressed course was our carefully curated music playlist featuring some of the finest Brazilian protest songs. I highly recommend adding it to your Spotify or preferred music platform!

To summarize our experience at the Design and Oppression Network: we initially asked ourselves, What can design do for the oppressed? But through these experiences—especially by recognizing that we are both oppressors and oppressed in different contexts—we came to a deeper realization. Instead of simply applying design to oppression, we needed to recognize the design that already exists within oppressed communities. The question shifted from What can design do for the oppressed? to What can the oppressed do with design?—acknowledging and elevating the forms of design already present in oppressed communities, even when they are not formally recognized as “design.”

To summarize in a single sentence: the Design and Oppression Network is currently exploring design by the oppressed, for the oppressed, with the support of occasional allies—those who may not have been historically oppressed themselves but who wish to stand in solidarity because they recognize the fundamental injustice of oppression.

Our fight is against all forms of oppression. If we only address certain forms while ignoring others, we risk allowing oppressors to simply shift from one form of oppression to another. I would love to hear your thoughts and have a meaningful conversation. Thank you very much. If any other members of the Design and Oppression Network would like to add anything, please feel free to join the discussion.

References

Van Amstel, F., Sâmia, B., Serpa, B.O., Marco, M., Carvalho, R.A.,and Gonzatto, R.F.(2021) Insurgent Design Coalitions: The history of the Design & Oppression network, in Leitão, R.M., Men, I., Noel, L-A., Lima, J., Meninato, T. (eds.), Pivot 2021: Dismantling/Reassembling, 22-23 July, Toronto, Canada. https://doi.org/10.21606/pluriversal.2021.0018

Designs of the Oppressed open educational resources.