Sustainable design (Design Theory 4) is a regular 30-hour course from the Design bachelor at UTFPR. My approach for this class was to avoid discussing sustainability as a technical issue and rather to deal with the political challenges of sustainability, the crisis of modernity, and the Anthropocene, in a similar way it was done in Carnegie Mellon University’s Transition Design seminars.

To understand the role of everyday politics in sustainability, I asked the students to keep their dry trash for an entire week and shot a portrait of themselves together with their trash. This initial activity generated a good debate in the second class, with some students blaming themselves for overconsumption, while others blaming designers for unsustainable packaging design.

Then, we paid a visit to UTFPR’s Green Office, an outreach program aimed at the construction industry. There students learned that there are plenty of sustainable materials and devices to choose from.

Back to the class, we explored the contradictions that keep our society away from sustainability, i.e. the roots of wicked problems such as pollution, garbage, and CO2 emissions. We used the interaction design theater to examine the stakeholders involved and their relationships.

At this point, the design students already noticed that it is incredibly difficult to convince people to change their attitudes and move towards sustainable behaviors. Design cannot expect people to choose the sustainable option just because it is more rational, logical, or beautiful. The field of designing for behavior change brought up new resources for designing in this situation. The second assignment required them to look for a pattern in the Design with Intent toolkit and apply it in an imagined intervention in his or her family. They used improvised videos to generate an intervention scenario.

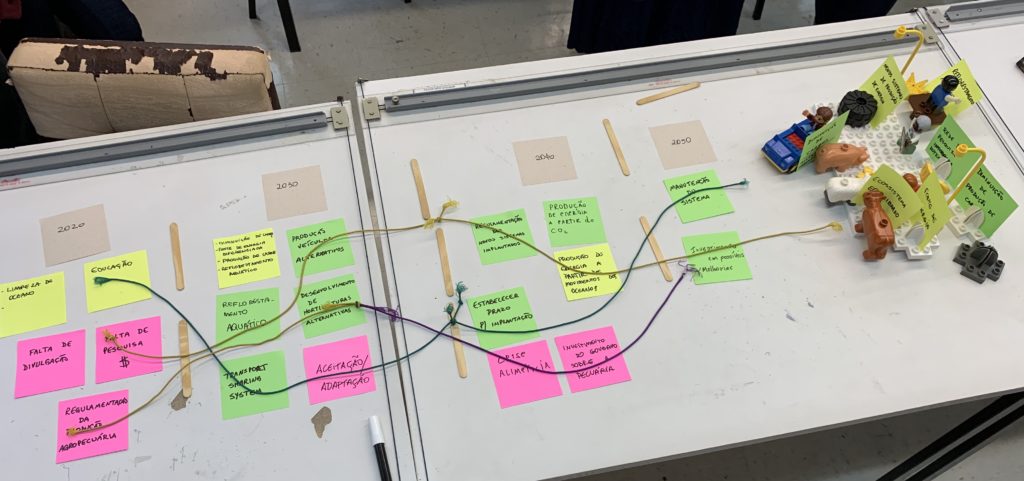

Even if the small scale interventions worked, the problem would not disappear, since the lack of sustainability is a large scale problem that affects multiple families and also several non-humans beings. Change at this scale is harder to imagine than an apocalyptical ecosystem reset that brings humanity back to the stone age. The tools developed by CMU are quite useful in speculating how accumulated micro-scale interventions can generate medium and large scale changes in the long term. Backcasting was quite useful for that.

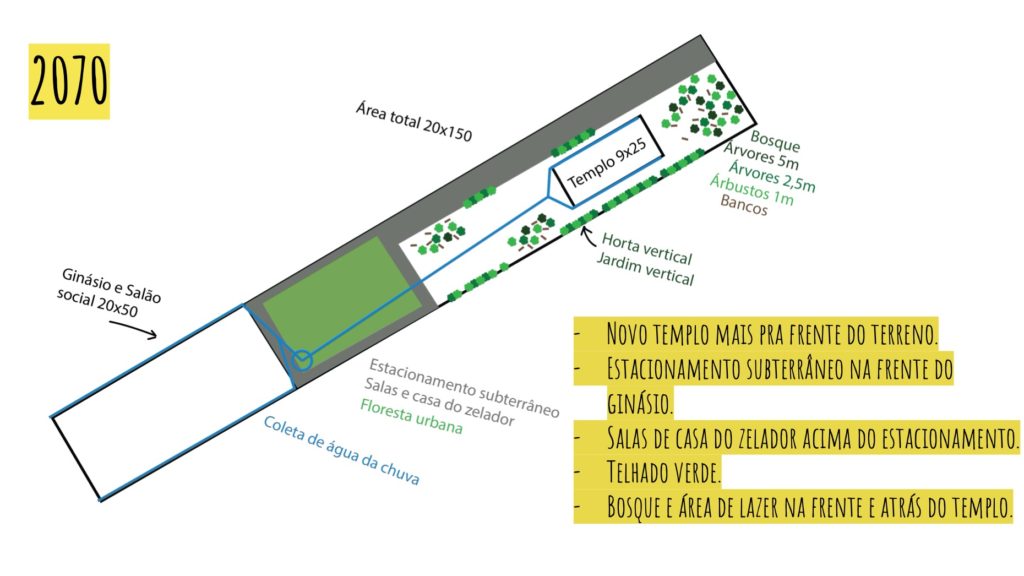

The final assignment for this class involved going to a real community, conducting a rapid ethnographic ecological study, and devising sustainable transitions to that community. The transitions could include as many design interventions they would like but had to be solidly justified on the evidence collected in the study.