Keynote, VIII Sustainable Design Symposium, UFPR, 2021.

Abstract: Design research has historical roots in the modernity project, which violently subsumes non-modern diverse cultures into colonized monocultures. Design research is also well-grounded in the development discourse that justifies unequal exchanges between nations, institutions, and communities. However, design research is also a realm of dispute where critical design researchers can stand against colonization and underdevelopment. In the last few years, these researchers have shown that the decolonization of design research can open up the field for several courses of development that do not reproduce the same contradictions of modernity. For example, the elusive concept of the pluriverse provides an alternative pathway for development: a universe in which many universes coexist. Inspired by this concept, critical design researchers are trying to overcome the modern contradiction of nature versus culture and its false solution: sustainable development.

Slides

Video

Full transcript

I will present decolonizing design research towards the pluriverse and some reflections I’m having, mainly because I engaged with this concept through the events and the great conversations that Lesley-Ann Noel is organizing worldwide. I hope she will explain and take the practical aspects of pluriversal design better. I will focus more on what we can do with this concept in places like Brazil and other regions in the global south or former colonies.

My positionality in this discussion is as a White cis man working in Brazil. Usually, I have quite some privileges in Brazil. But when I join these international events it is like when I was doing my PhD in the Netherlands: I have fewer privileges. My position was not that of a White man; I was perceived as a Latino person, perhaps seen as less rational sometimes. I got angry about that. Since returning to Brazil, I have been studying decolonizing and decolonial literature.

My current position at the university is in service design and experience design, where I try to bring an anticolonial lens to this area. I will start with a few words in Portuguese because we are hosting this conference in Brazil.

[SPEAKING PORTUGUESE]

I’m sorry if you don’t understand Portuguese. What I was telling my fellow colleagues who understand Portuguese is that what happens in Brazil is also universal. It’s not just something interesting for Brazilians themselves. For example, we have this water crisis right now for many reasons—climate change and deforestation in Brazil’s savanna area, the Cerrado. The Paraná River, one of the biggest rivers and the water that flows through South America, is almost dry. It’s one of the toughest water crises in our history. And this is not just happening in Brazil. If we focus on researching sustainable design in Brazil, on the water crisis in Brazil, decolonized design in Brazil, we miss the point.

If we fight a colonial universal, we must find other universals to contrast them. What I’m proposing with this short presentation is to reframe the environmental crisis in Brazil and other places as an existential crisis for both human and other-than-human beings. Existential threats are usually distributed unevenly. Some beings are more human than others. And by that, I don’t just mean homo sapiens. Dogs and cats are very human. Sometimes, dogs and cats in privileged places and countries get more investment, more money, and more resources than homo sapiens living in other parts of the world. There are also disparities, even larger ones, regarding vegetables and different kinds of animals. They are threatened as long as they are not considered part of this specific human culture.

For example, look at the unequal distribution of the COVID-19 vaccines across the world. In Africa, large parts of Asia, and even Latin America, vaccines are not coming as quickly as they did in places with the ideal concept of humanity being developed and spread to the entire world. The ones who deserve to live and exist in these situations are only those who have accumulated resources for centuries. Through unequal exchanges, they can say, “We have the money, so we can purchase the vaccines.” But that’s not entirely fair if you consider that money is just a recent invention to make such decisions in the history of humanity. If you take a long perspective, that’s so unfair.

So far, design research has addressed the environmental crises mostly by finding ways to reduce, reuse, and recycle resources. A critical sustainable design discourse already shows that reducing consumption will not resolve the environmental crisis, much less the existential crisis. To address the existential crisis, I suggest design research faces the historical contradictions behind them. Taking a long perspective and considering what has been neglected and the tensions accumulating in our societies, we usually don’t want to address them.

The existential crisis, for example, can be traced to the contradictions harbored by the modernity existential project. There are many ways of talking about these things. People might say it’s the Enlightenment, colonialism, imperialism, capitalism, or racism. I want to join all of them under a single concept: modernity. But I want to qualify modernity because many people criticize the modern world and modernity. Modernity is an existential project, a way of existing in the world and trying to exist in the future, sustaining your existence. It’s a collective existential project.

This existential project consists of realizing a universal way of being human, specifically the white, Western, North Atlantic, and European anthropos. Today, people say, especially in the sustainable design discourse, that we live in an anthropocentric world. They call this age the Anthropocene because humankind is the strongest force shaping the Earth. I wouldn’t say so. If every human being was considered to be human, then we could say we live in an anthropocentric world. However, we live in a Eurocentric world, or perhaps a North Atlantic-centric world, as the United States also heavily relies on these universalities to position itself in the world and continue accumulating privileges.

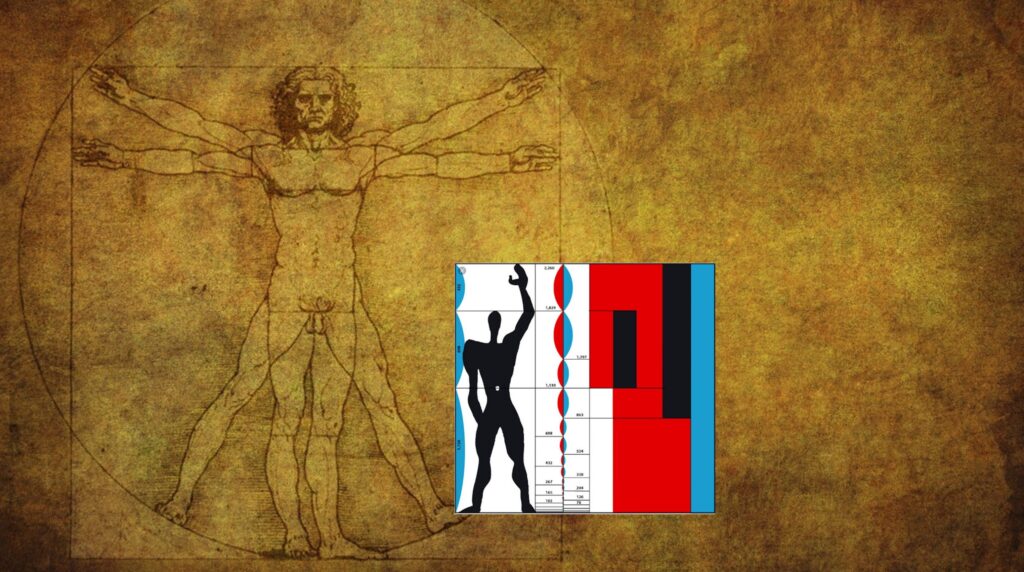

This modernity project and its universal notion of the human being profoundly affect culture, especially modern art and modern design. Here, I show two pictures of an ideal man. I mean the ideal man, because it’s a man—a male human. Even though 500 years have passed from one picture to the other, from Leonardo da Vinci to Le Corbusier, it’s still the same kind of man. Why man? Because it’s a universality taken by design research, art, and many other fields as a standard for designing and making decisions about functions and forms for humans.

The positive aspect of this existential project is evident. The negative aspect is that to realize this universality, you need to erase, ignore, and downgrade other ways of being human because they are not ideal or less developed. This modern existential project subsumes other collective existential projects. Colonialism, racism, and the way indigenous people were hunted or enslaved, especially those from Africa, put their existence at stake, treating them as mere objects or instruments for realizing the modern existential project. Their nations, ideas about humanity, and relationship with nature were totally ignored.

Colonialism justified unfair exchanges with allegedly inferior existential projects in other parts of the world. Colonialism didn’t just impact human cultures but also caused animal extinction, deforestation, desertification, and pollution in places where this had never happened before. Europe had experienced deforestation before colonization, contributing to the motivation to find new worlds to extract resources and wealth. Colonies developed quickly, but the metropolises benefited more, enriching themselves at the colonies’ expense.

Colonization created opportunities for capitalism and other systems of oppression. To address an existential crisis, we must look back to colonization because threats like those highlighted by the Black Lives Matter movement have historical roots in colonialism. The primitive accumulation of capital in Portugal and Spain from resources extracted from Brazil and other places in Latin American and the Caribbean, transformed into means of production by other nations, spurred the Industrial Revolution. Therefore, industrial design, stemming from the Industrial Revolution, also comes from colonialism.

Modern colonialism might be nearly over, but traces of coloniality persist in power, knowledge, and ontological relations. A Latin American group of researchers called Modernity/Coloniality has done remarkable work exposing this lingering coloniality in institutional relations, universities, and self-perceptions.

In my view, design is historically associated with a specific form of coloniality: the coloniality of making, reproduced through international production relations. This concept was developed from Brazilian philosopher Álvaro Vieira Pinto’s work, not yet widely known even in Brazil, where he lived. Paulo Freire, a collaborator, considered Vieira Pinto his philosophical master. Concepts like conscientization come from Vieira Pinto’s work. He had insightful remarks about design and making, which were overlooked due to the coloniality of knowledge that prioritizes foreign over local knowledge.

Vieira Pinto’s derived concept of coloniality of making prioritizes developed nations’ intellectual labor over underdeveloped nations’ manual labor. Developed nations design and theorize design, while underdeveloped nations merely make or practice design. This creates a theoretical and methodological dependence that affects the autonomy of design students, entrepreneurs, and communities trying to make sense of their conditions.

For example, the human-centered design toolkit, created to assist developing nations, instead creates dependency on foreign theories and methods, limiting local autonomy. Despite this divide, a radical movement questions design’s role in coloniality while seeking alternative theories and practices. The decolonizing design movement acknowledges, dismantles, repairs, and compensates for what the colonized have lost, supporting various existential projects.

The concept of the pluriverse has become influential in this movement, promoting the coexistence of different existential projects. Arturo Escobar’s 2018 book has inspired many, but some prefer using pluriverse over decolonizing for easier understanding.

I’d like to reflect further on this concept. Usually, Arturo Escobar defines a pluriverse based on the motto of the Zapatista liberation fighters in Mexico. We can live in “a world that can fit many worlds”, so we don’t need to exterminate other worlds through war. We can have some “peaceful war” that liberates people without excluding others. However, many people forget the Zapatista history, mainly that they went through a real war, although it was very different.

The pluriverse, as Escobar explains, is often seen as the opposite of the universe. Some interpret this as forgetting anything that comes through colonialities and sticking to what we already have in our localities. Some people take the concept of the pluriverse into practice by focusing on each local community, doing their own thing, their way, without much interference from others.

I think this interpretation is not heading us in a good direction. If you interpret the pluriverse this way, you might reproduce strategies to prevent colonial movements from growing and presenting radical structural changes in society. For example, the melting pot theory in the United States suggested that cultures could mingle together and become one big nation. A similar movement in Brazil in the beginning of the 20th century involved the whitening of Black and Indigenous communities through state-stimulated hybridism and mestizaje. These minority cultures lost space and felt they could not fight against what had been colonized in the past. They couldn’t ask for reparation because this multicultural policy was considered a living utopia.

I would like to rephrase the pluriverse as a universe that can afford several conflicting universes. If we keep the possibility of fighting back, questioning, and not settling the colonization, then we can have an interesting utopia. Going hyperlocal and rejecting universals don’t favor the decolonization struggle. Instead, they favor the colonialist argument for civilizing the underdeveloped. Metropolises claim these communities have no knowledge, and thus, they need to impart knowledge to them to survive in a globalized world.

As I argue in an upcoming book chapter on decolonizing design research, we need to fight universals with alter/native universals, not particulars. Design research can help us universalize Southern particulars. Here, I use Southern not in a geographical sense because in Brazil, the geographic South is richer and colonizer, and the geographic North is weaker and colonized. But epistemologically, the North is the South of Brazil because it has been neglected in our history. We can look at this South and find what is universal in that particularity, which can be useful for other neglected places.

For instance, the South has plenty of designs by other names, as Alfredo Gutiérrez Borrero, a Colombian researcher, states. He created the concept of “diseños otros” to relate what we call design to something not recognized as design but playing a similar role in different cultures. We can respect that they already have a way of making and producing their existence and then relate those concepts to Northern designs, not the colonialists’ ways of doing design.

I would add to Gutiérrez Borrero’s understanding that this can be equi-alter-potent against decolonization. He has written extensively on Sumak Kawsay, Mingas, Ubuntu, Hind Swaraj, Jugaad, Gambiarra, Anthropophagy, and the likes. I have also written about it, finding inspiration for designing differently. Instead of being included in design research as modernity fixes, these concepts should be included as modernity resistance.

Every design research project is part of a collective existential project—community, institution, university, nation, a world that can sustain specific beings. We can address existential crises differently by scrutinizing the collective existential projects we contribute to our research. My main takeaway questions are: Whose existence is at stake with this project? What are the qualities of that existence?

I am investigating various projects. The Corais Platform has more than 700 developed in the last 10 years. I won’t discuss them now, but you can check my website for more information. In this revised version of the pluriverse, these inclusive existential projects of the South can fight and dismantle the exclusive existential projects of the North. It seems difficult until we realize that decolonizing can join forces with depatriarchizing, decapitalizing, abolishing, declassifying, unsettling, and other counter-hegemonic efforts.

Thank you very much. [SPEAKING PORTUGUESE]. I’m curious to hear from Lesley-Ann Noel and to answer any questions you might have.

References

Noel, L.-A., Ruiz, A., van Amstel, F. M. C., Udoewa, V., Verma, N., Botchway, N. K., Lodaya, A., & Agrawal, S. (2023). Pluriversal Futures for Design Education. She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation (Vol. 9, Issue 2, pp. 179–196). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sheji.2023.04.002

Van Amstel, F. M. C. (2023). Decolonizing design research. In: Rodgers, Paul A. and Yee, Joyce (Eds). The Routledge Companion to Design Research (pp. 64-74). Routledge. https://www.doi.org/10.4324/9781003182443-7

Saito, C., Freese Gonzatto, R., and van Amstel, F. (2024) Anticolonial prospects for overcoming the coloniality of making in design, in Gray, C., Hekkert, P., Forlano, L., Ciuccarelli, P. (eds.), DRS2024: Boston, 23–28 June, Boston, USA. https://doi.org/10.21606/drs.2024.255

Van Amstel, Frederick M.C and Gonzatto, Rodrigo Freese. (2020) The Anthropophagic Studio: Towards a Critical Pedagogy for Interaction Design. Digital Creativity, 31(4), p. 259-283. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/14626268.2020.1802295

Escobar, A. (2018). Designs for the pluriverse: Radical interdependence, autonomy, and the making of worlds. Duke University Press.

Gutiérrez Borrero, Alfredo (2022). Designs of the Souths, Designs-other, the designs from and to other worlds. ICDHS 13 International Conferences on Design History and Studies. Universidad Jorge Tadeo Lozano, Bogotá, Colombia.