This talk was part of the Royal College of Art Symposium on Design and Systemic Change, organized by Product Design students.

Abstract: Oppression is systemic as it is reproduced across social groups, generating complex patterns of domination. What can designers do to stop such reproduction? First, they need to acknowledge their role on the oppressor’s side, and then they may join the oppressed on the opposite side. Developing such critical consciousness requires understanding how multiple oppression intersect and transect.

Video

Slides

Audio

Full transcript

Can designers change systemic oppression? I will state this question and try to answer it quickly. It’s more like a provocation. I’m going to touch upon some issues that previous panelists have raised. However, I’ll frame them from the perspective of the Global South, particularly Latin America, where people have thought thoroughly about systemic oppression. Before that, I must answer three underlying questions: 1) What is oppression? 2) Why is it systemic? 3) What can designers do?

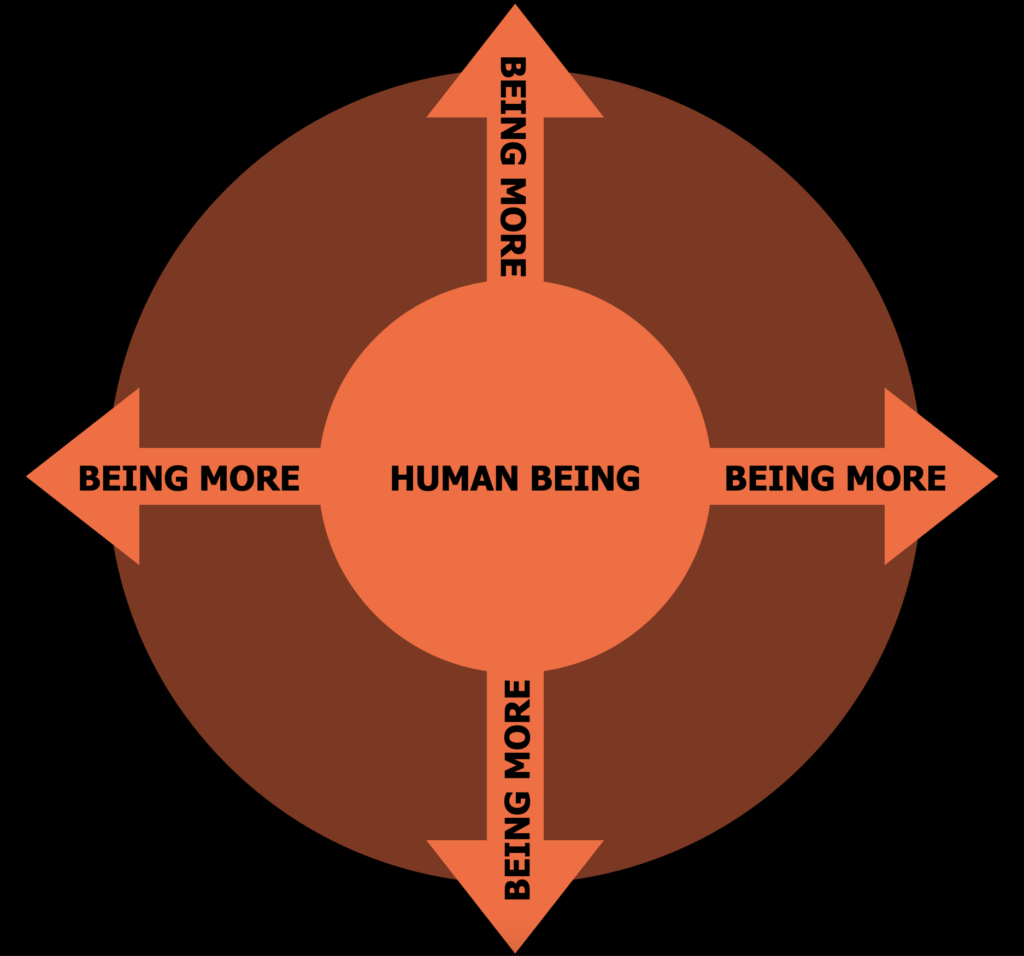

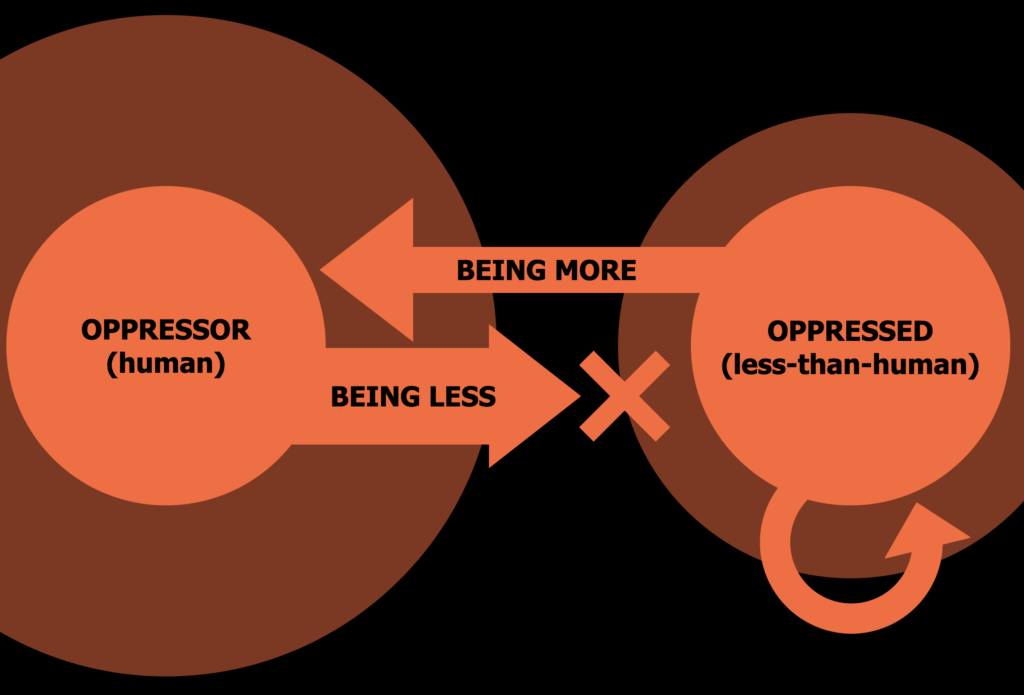

I will summarize graphically the ontological vocation of human beings or theory of human development/liberation proposed by Frantz Fanon, Álvaro Viera Pinto, Paulo Freire, Augusto Boal, and other authors. They all state that humans are born to become more and to develop further as they have an expansive nature. Humans are always trying to challenge themselves, doing new things, and becoming something they are more than they already are.

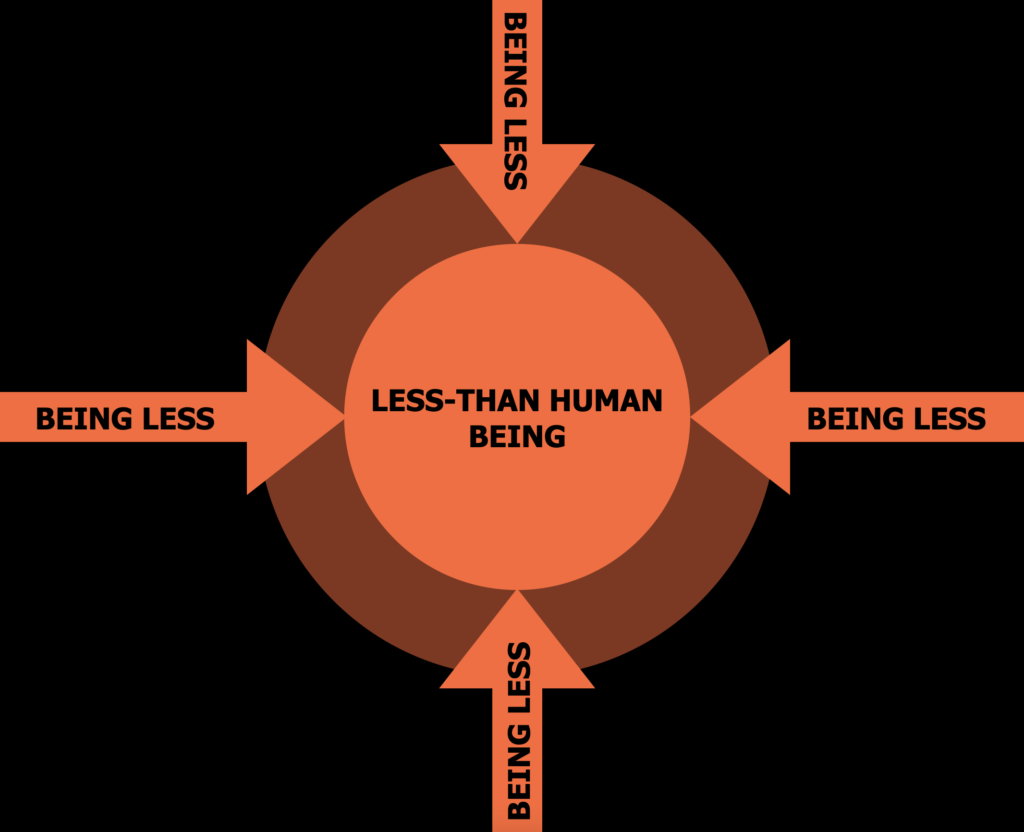

However, due to some specific historical conditions, they are oppressed. Oppression is a social relation that curtails this ontological vocation. Instead of having this expansive force of being towards the world, the world pushes back to become less than possible. Due to that constant force, this less-than-human being is treated like a thing or an instrument of another human being, the oppressor in that relation.

The oppressed are less-than-human, women, Indigenous, Black people, immigrants, disabled, users, and many other kinds of social groups created by the oppressors to manage the oppressed and to justify why the oppressed need the oppressors. Who are these oppressors? Well, they are the ones who concentrate material privileges: so-called humans, men, colonizers, White citizens, able people, designers, and so on.

| Oppressor | Oppressed |

|---|---|

| Human | Less-than-human |

| Men | Women |

| Colonizers | Indigenous |

| White | Black |

| Citizens | Immigrants |

| Able | Disabled |

| Designers | Users |

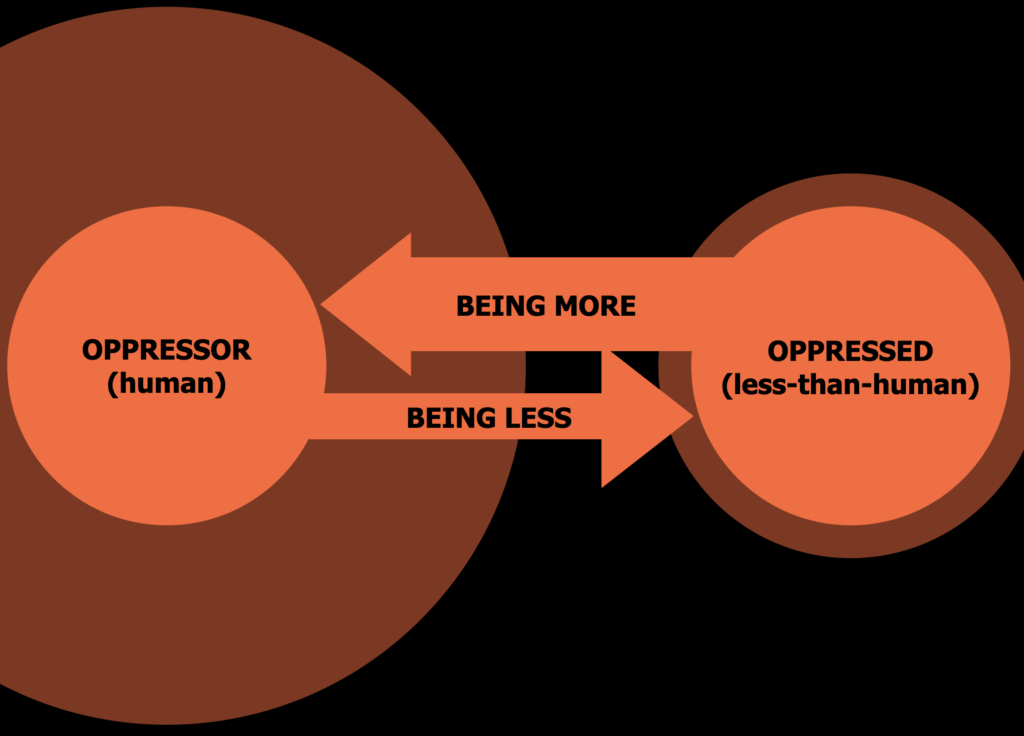

To put it graphically, this double relationship: on the left side you see the oppressor, the human who states “I am the human”, and, on the right side, is the oppressed, the human who has to hear what the oppressor says: “you are not human, or at least you lack some humanity. Nevertheless, I can exchange that humanity for something you produce that pertains to me, such as natural resources. I can exchange that for a designed and manufactured product so that you can humanize like me”. The being more of the oppressed is pulled into the oppressor, and it doesn’t return back to the oppressor in the same way. Instead, what the oppressed receive is being less, a product that is a testimony that the oppressed lacks something. The product is ready-made, and it does not take into account the oppressed history, needs, and capabilities.

In the long run, the oppressor develops much more than the oppressed in this unequal exchange. Therefore, the oppressor starts to define a standard for being human, for humanizing and becoming human. The consequence of oppression in design is that we understand design as if it were the single way of humanizing our world. Yet these worlds are so different because the oppressed and oppressors are designing their worlds differently.

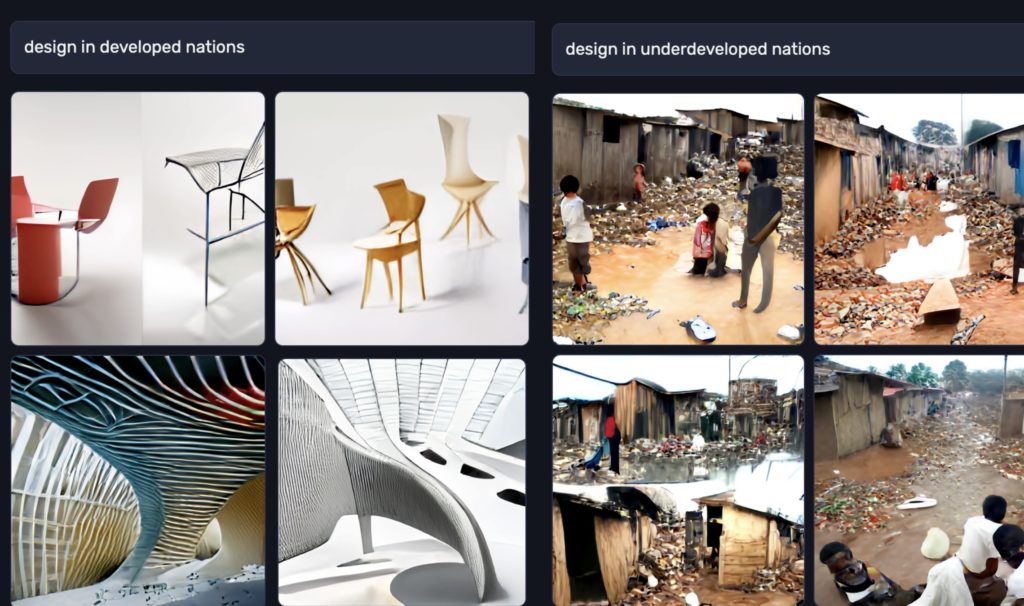

For example, if I use Craiyon, an example of an AI image generator machine currently available, and I type “design developed nations” and “design underdeveloped nations”, you can clearly see the stark difference in what design means in these two worlds. When the AI shows these pictures of slums in underdeveloped nations, it implies that design is lacking. The pictures make you think that slums are not designed or inferior designs. I prefer to call them designs of the oppressed.

However, if you look at the overall picture, if you get the numbers, you see that the design done in developed nations has a much larger carbon emission footprint than in underdeveloped nations. Slums, in the long run, have a much smaller footprint. The garbage that you see in the slums comes originally from developed nations, not from underdeveloped nations. Developing nations are exporting garbage; therefore, design in developed nations looks like that oppressed. If you look critically into that, you completely change your perspective.

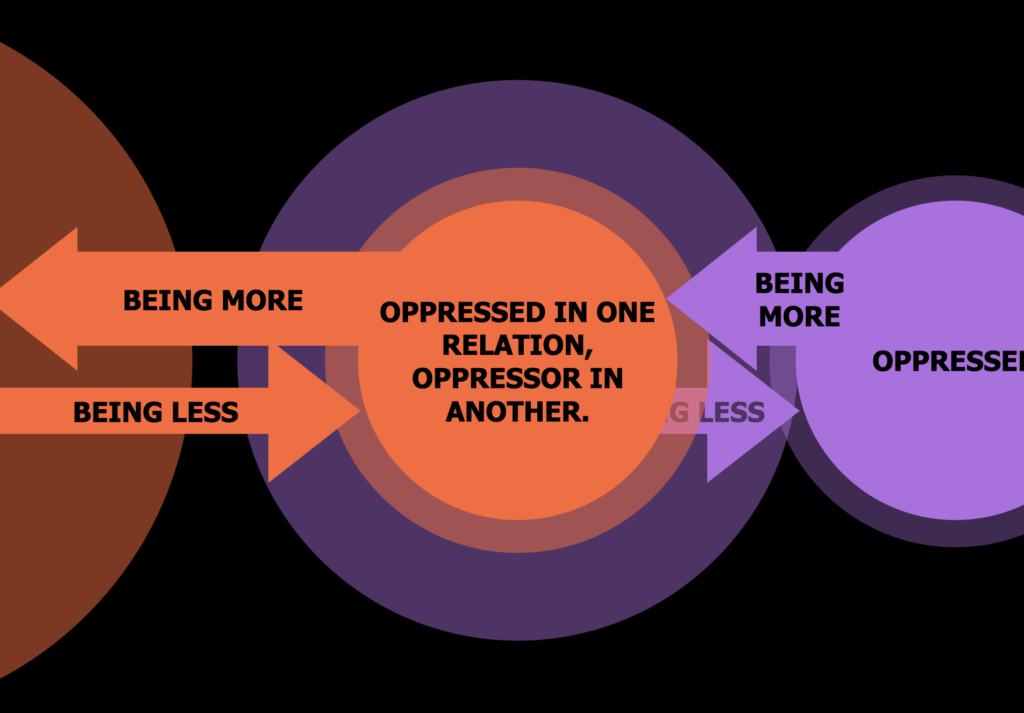

Why is this considered to be systemic? It’s because the oppressed typically reproduce oppression towards another social group. The same person who is oppressed in one relation can become an oppressor in another. For example, a male worker can be an oppressor towards a female companion because these oppression relations are interconnected. You cannot look at class oppression without looking at gender or race.

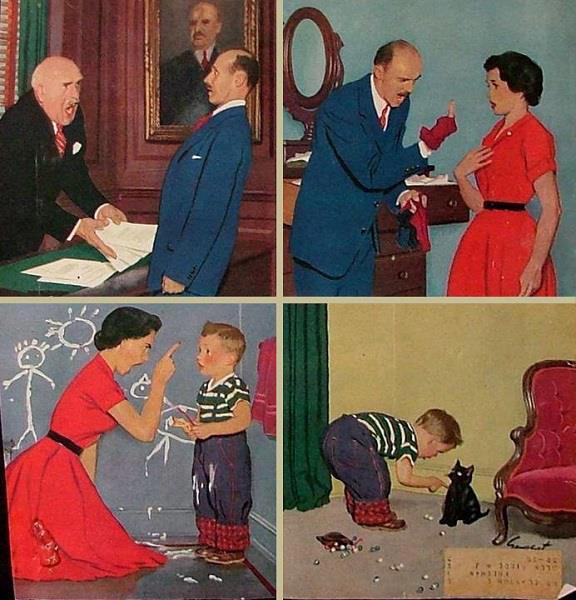

The oppressed want to become like the oppressor because the oppressor is designing the standard for being human. Looking powerful and being reckless towards others is the standard that the oppressor builds in our subjective feelings and also in culture. That can be exemplified with this nice painting by Richard Sargent, Anger, Transference. You see the boss yelling at the employee, the employee comes home and yells at his wife, and then the wife yells at her children, and the children yell at the cat.

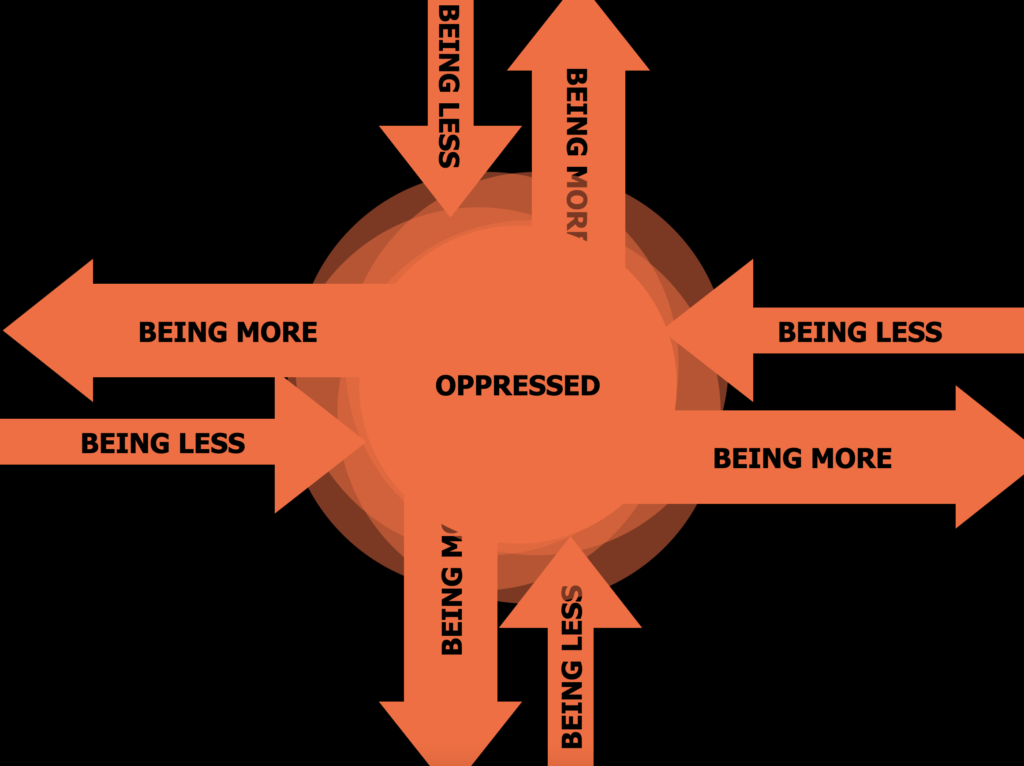

This is a simplified way of understanding oppression as a chain of consequential actions. However, something is missing here. There’s a lack of diversity of different kinds of oppression. You only see White people in the picture. That is something that Black feminists in the United States have done quite some work on developing an intersectional perspective over oppression. The oppressed are not only oppressed by one relationship but by multiple as if they were in a road intersection with so many cars crossing over and threatening the life of the oppressed. Kimberlé Crenshaw, Patricia Hill Collins, bell hooks, and Angela Davis, all wrote about how, for example, a lesbian Black unemployed woman in the US suffers much more from oppression than a White man like me in Brazil. However, I am not precisely White in the US.

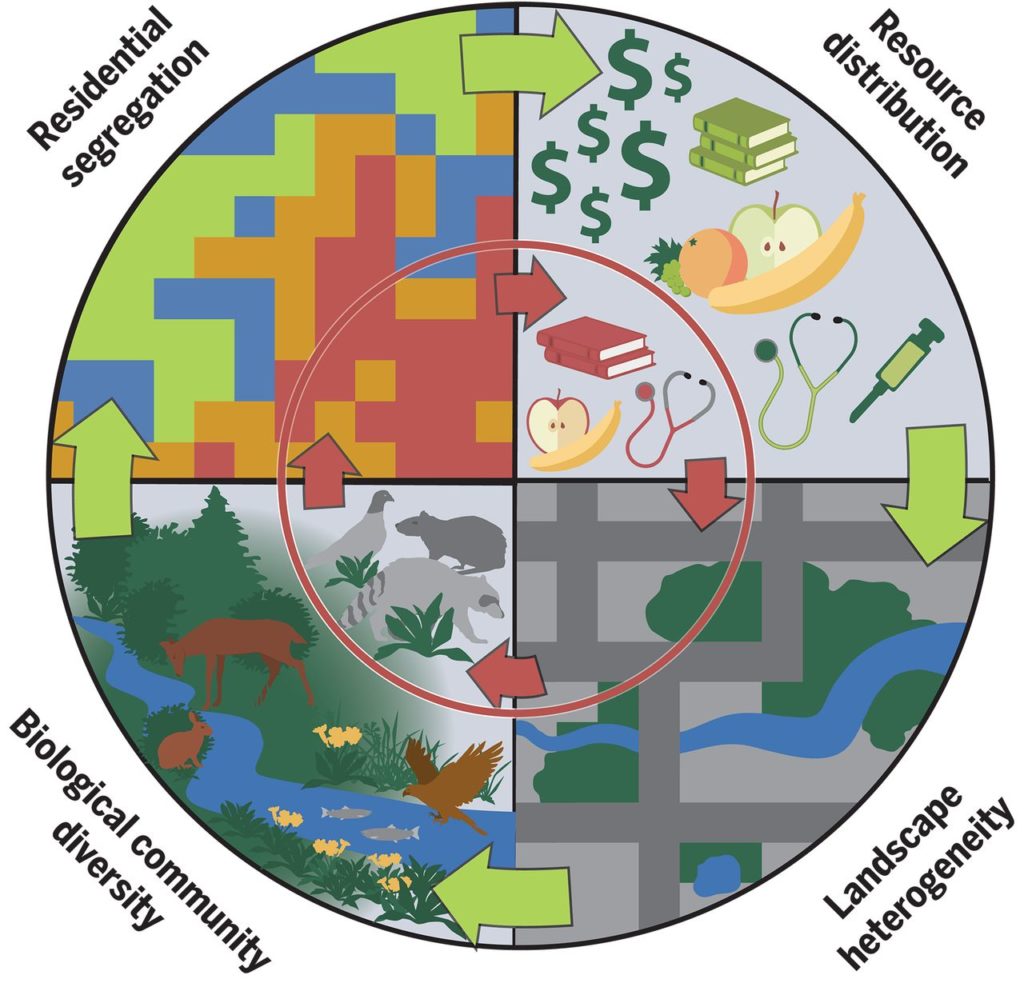

This has a larger impact. If you put the environment into the equation, you see that the intersections of oppression also affect oppressors. The oppressors use their advantages to adapt and anticipate, for example, environmental damages and shield them from instability, as shown by several research on environmental racism. I’m just picking one here that says residential segregation, an outcome of social inequality, can be explained through oppression theory. Segregation causes resource distribution inequality. People who live in deprived areas need to eat more impactful food and produce more garbage. Due to that, their surrounding landscape becomes less heterogeneous, and biological diversity diminishes, affecting the oppressors in distant areas. However, the oppressors can build parks in their neighborhoods and send their children to the Moon or Mars to colonize another world…

Ok, but how do we get out of oppression? Well, liberation theory says that the oppressed can counter the oppressor only if they reject that oppressed standard of humanizing and become more for their own sake. What can designers do in this liberation fight if the oppressed should not be anything like the oppressor and adopt the same consumption standard?

Well, take once again a look at these classifications in the table that I showed you before. In the last row, you see that designers are on the oppressor side while users are on the oppressed side. Yes, that’s hard to admit, but designers are already systemically oppressing users if they are designing for them. That’s a very provocative finding from our research on user oppression in the field of human-computer interaction. I don’t have enough time to go into details, but to summarize, if you reduce a person’s ontological vocation of being more to a user of anything that you are designing, be that a service, a technology, an interface, or whatever, if you consider that person cannot design that thing that you’re doing, you are oppressing that person.

So, there is not much you can do against oppression on the oppressor side. You cannot fight oppression as a designer and only as a designer. You need to side with the oppressed to fight oppression. You need to side with the users and the other kinds of oppression I showed you before. But bear in mind that you are also oppressed. You have to find which kind of group you are that is also oppressed to make a bridge or an analogy to the oppressed situation of the ones you want to work with.

For example, to give you a glimpse of how this can happen and how you can realize that. Consider that design workers are oppressed, not because they are designers, but because they are workers in a capitalist work exploitation relation. So are women designers. They are oppressed not because they are designers but because they are women and also workers in a simultaneously sexist and capitalist society.

Once you find out that, what we do here at the Laboratory of Design against Oppression, is join the oppressed as an oppressed, not as an almighty “deusigner” that can save them. We use the word “Deus” next to “designer” because it means “God” in both Latin and Portuguese. A deusigner has this divine system-thinking approach to wicked problems that no one has ever noticed. That’s not the way you can fight oppression. This way, you will oppress instead of liberating. To liberate, you have to join the fights already going on by the oppressed

So, in 2022, we joined Uniperifa, a group of peripheral students and activists living on the poor outskirts of Curitiba city. They wanted to increase their access to public universities in these areas so that students become more conscious of the importance of achieving higher education for their communities. Then, in October of that year, we hosted this marvelous co-design workshop with Condominio Iguaçú inhabitants to design community actions together.

While looking at the map we designed, we noticed several sustainability issues. For example, garbage collection that the mayor and the city didn’t want to take care of. They realized they had to convince the inhabitants of the residential area to organize and push their demand to the city hall so that public garbage collection would reach the area. However, organizing is always challenging for the oppressed because they are separated into many social groups with nothing in common.

Therefore, we decided to focus on the community center to start moving things around. Based on the co-design workshop, we organized this community center renovation, and our design students joined the community members to paint and fix what was broken so that the community center could become a symbol of what the community can do together. Our design students joined a process that was already going on. We just needed to join forces and do the work, that is all.

That’s a very simple example of how our design students are learning to change systemic oppressions little by little, joining the oppressed and designing and making things with the oppressed, by the oppressed, and for the oppressed so that they can become conscious of their role in this social relationship. They will eventually understand how to stop oppressing and fight for liberation. That’s it for now, thank you very much.

References

Gonzatto, R.F. and Van Amstel, F.M.C. (2022), “User oppression in human-computer interaction: a dialectical-existential perspective”, Aslib Journal of Information Management, Vol. 74 No. 5, pp. 758-781. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-08-2021-0233

Van Amstel, F. M., Noel, L.-A., & Gonzatto, R. F. (2022). Design, Oppression, and Liberation. Diseña, (21), Intro. https://doi.org/10.7764/disena.21.Intro

Lucy Pei, Edgard David Rincón Quijano, Angela D. R. Smith, Reem Talhouk, and Frederick van Amstel. 2022. Assets and community engagement: a roundtable with HCI researchers and designers. interactions 29, 5 (September – October 2022), 44–47. https://doi.org/10.1145/3554975