Every community practices the design of itself, as Arturo Escobar has pointed out in his book Designs for the Pluriverse. How can this metadesign process be more creative, imaginative, and conscious? Lego Serious Play can support Community Design in a few ways: materialize abstract values that a community wants to express, map community assets, anchor conversations about complex services, identify the most pressing contradictions to tackle, and plan community action. This lecture provides the background research, examples, and limitations of this method when supporting design in communion.

This is a post-recorded lecture from the MXD Spring 2024 Graduate Seminar, University of Florida.

Video

Full transcript

Community design with LEGO Serious Play is an approach in which a community can design itself using LEGO pieces, leveraging the historical role that play has in the development of human cognition and social skills.

Children learn how to interact with other children and with other adults through play. These make-believe games are very important to develop imagination and creativity skills. This development does not cease with childhood; it grows and develops further throughout adulthood. However, it takes a different shape, a different form, and a different appearance. We could go as far as to say that sports are a kind of structured way of playing. That’s why athletes sometimes celebrate their achievements in make-believe rituals, like the Brazilian national team did during the last World Cup, which has been criticized. On the other hand, they remind us that sports come, at least historically and culturally, from childhood play.

I’m going to focus on a specific toy used to support several kinds of play. It’s called LEGO. It’s a system to build many kinds of toys. The LEGO patent registered in the middle of the 20th century highlights the modularity characteristics of this playing material. By following simple rules attached to the material itself, a child does not need to learn abstract building rules before trying it out; they can immediately use the material to learn how to build. It’s a system with immanent features that can be learned by doing, allowing for many different kinds of emergent performances.

LEGO has evolved to become one of the largest toy manufacturers in the world. However, in the 1990s, they faced a crisis due to growing competition from video games and other toys. They didn’t have the same kind of appeal as video games at that time. Initially, they tried more complex and integrated challenging puzzles for LEGO sets, but that didn’t work, and the company was almost bankrupt. At some point, the president of LEGO had the idea that maybe LEGO itself could be used to insert more creativity into meetings at LEGO. He partnered with two university professors who developed the method called Lego Serious Play. These professors wanted to encourage in-house innovation at LEGO. After trying it out inside LEGO, they extended the method so it could apply to any organization. LEGO even created and produced a LEGO Serious Play introductory set. There are many other sets and custom-tailored sets for LEGO Serious Play. I have a custom-tailored LEGO Serious Play set based on Duplo. There are also books, conferences, and training sessions. I will present a short introduction to what LEGO Serious Play can be in the context of community design.

This method has been very important for LEGO’s revival. The company grew by introducing ideas of having licensed heroes from existing brands as themes for new sets. This exploration is nicely synthesized in the LEGO movie. The contradictions of playing and working are also part of this movie, which is very interesting to watch. I recommend it as additional material if you haven’t watched it before. The LEGO Serious Play method has many different techniques, but the most important one is the metaphor. What you build with LEGO Serious Play is not a realistic one-by-one or one-by-ten scale of the object you’re representing. You are using an analogy scale. What you represent is never something directly related to your objects; your presentation is different from the object of representation. This is called a metaphor in linguistic studies. For example, a LEGO piece that doesn’t resemble a dinosaur can become a dinosaur if you add a story to the set. Interpretation is required because the shape of the model is not explicit. This is where creativity has space to flourish, and storytelling, the second most important technique, connects tightly with metaphor.

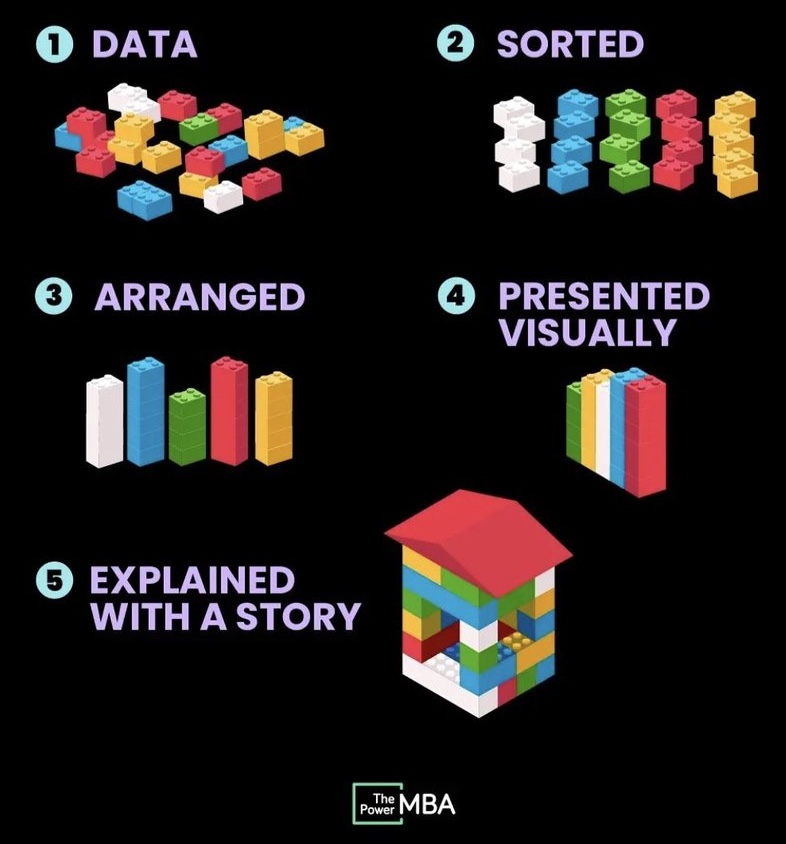

In design research and science, there is always the challenge of presenting findings in a way that someone who hasn’t gone through the process can understand their consequences and importance. Many scientists and design researchers refer to a diagram that has many versions and has become a meme on the internet. Data is just pieces scattered together and sorted. You organize them by some rules, like color, arrange and connect them to express a quantity and present them visually through graphs and charts. However, the most powerful way for someone who hasn’t gone through the process to understand is through storytelling with LEGO. With those LEGO metaphors, you have a good ground for storytelling so that the speaker does not get lost. Amateur storytellers sometimes diverge from their stories, but if you have a physical anchor, like a LEGO metaphor, your story becomes clearer and easier to follow.

There are many different ways to apply LEGO Serious Play. I will first focus on a few applications that pertain to community design. The most obvious one is when a community wants to express its values in a design product, such as a visual identity. In 2016, I partnered with community members of Curitiba traffic education schools in Curitiba and proposed that the community design its logo instead of having an expert like me or my students at the university. They were excited because the school existed due to the community of teachers, public school guards, drivers, and social workers who used the school for various educational and political activities related to traffic safety and education. Each co-designer in the workshop materialized their perception of the school’s value to the community using a metaphorical model. The metaphor materializes something hard to express through speech and creates an anchor for people to convey the value they want to express in the visual identity using the LEGO metaphorical model.

It’s powerful to quickly see the diversity and different perspectives and expectations of the visual identity project and the institution itself that the community wanted to support and develop further. This experience strengthens the bond among community members, mostly volunteers, making it a fun way to engage them. I won’t go into details on how this process unfolded later on; several phases didn’t directly involve LEGO. However, LEGO Serious Play was the spearhead of this process and set the tone for the co-design activity. It’s an excellent way to start, more than just an icebreaker because the LEGO Serious Play result can be taken further to the next step. The values represented using LEGO led to finding more imagery in scrap paper to create a collage. The next steps are described on my portfolio if you’re curious.

What I want to emphasize is that LEGO was key for us to get to this visual identity that the community felt included in. The final logo has three different persons with different colors, embraced by dynamic activity that represents traffic but in a safe, roundabout way, symbolizing the fun gathering that the community wanted.

LEGO Serious Play can do much more than this. It’s also used for producing maps of things that are not entirely known or known by some but not by others. In 2020, the Federal University of Technology Paraná Industrial Design Department asked me to help figure out all the outreach projects and promote synergies between them because the federal government wanted to emphasize outreach in public universities. We used LEGO Serious Play as a mapping activity. Each circle represents a set of outreach projects a professor is pushing forth, and the strings connect potential synergies between those projects, which are topics for future conversations. One synergy discovered was the possibility of working on outreach projects designed against oppression. Several professors later came together to form the Laboratory of Design against Oppression.

Before diving deeper into that story, let me introduce a more theoretical understanding of this situation. Designing a community is not commonplace; it’s usually related to organizing or the historical accumulation of culture. However, it’s also about design, as any community is always designing itself. This idea is described in the book “Designs for the Pluriverse” by anthropologist Arturo Escobar, who claims that a community always wants to become more than what it is and is always trying to redesign itself to have different spaces, activities, and even different bodies.

This concept of community design means the design of the community itself. When a community designs itself, it’s meta-design, the design of a design, creating complex arrangements of many entities that are hard to align and make sense of their relationships. This overall picture usually comes after the co-design process and can emerge from a LEGO Serious Play session. The basic distributed cognition principle behind it is that when dealing with complex situations, there is a lot of tacit knowledge, or knowledge not yet articulated into language or thoughts. You want to use and appropriate that knowledge because it’s part of the community. Laying down these elements on a table, roughly matching how they relate to the world, makes it almost like having the world in your hand. This manipulation and relation while speaking amplify meaning beyond what is said, as spoken language quickly attaches to the material language of LEGO Serious Play.

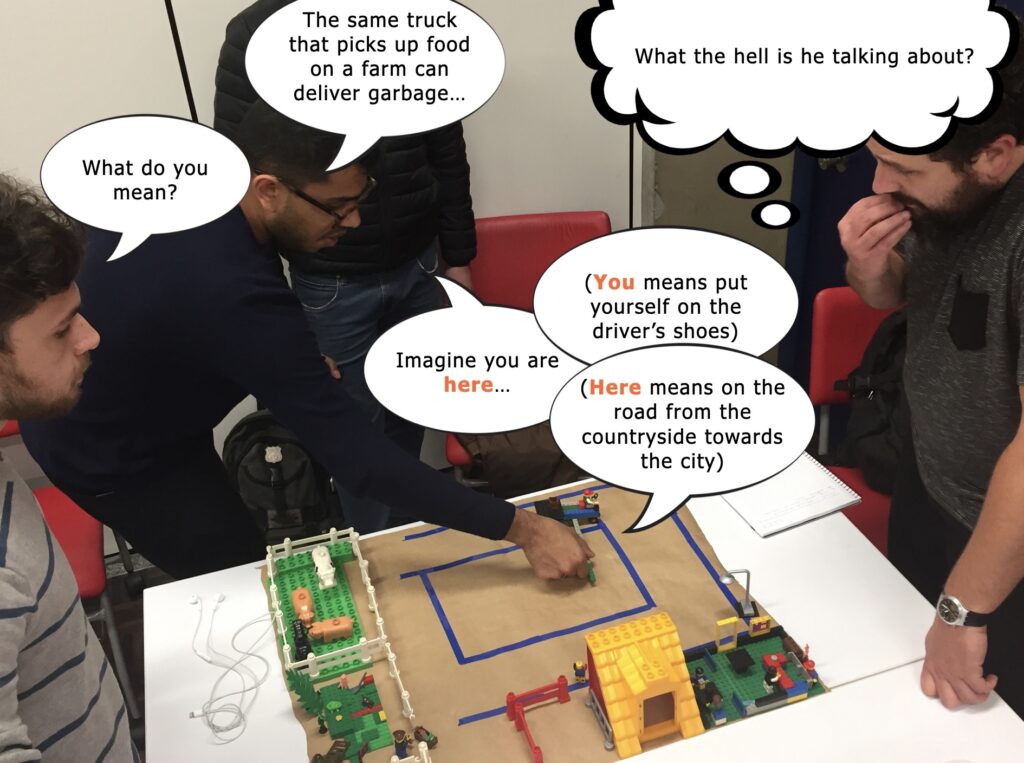

LEGO Serious Play is a metaphorical language, where things represented with plastic materials on a board, table, or hand do not reflect their exact shape but represent deeper concepts. It’s hard for others to follow new ideas that are difficult to convey, but LEGO metaphorical models help others reconstruct these ideas in their heads. For example, a person playing LEGO Serious Play pitches a new concept for service, explaining that the same truck that picks up food on a farm can deliver garbage. The collaborator, confused, asks for clarification. The pitcher uses LEGO language to explain, pointing out and asking the collaborator to imagine the scenario, locating the idea in a relationship between community entities.

There’s a video where they record an amplified version of LEGO Serious Play by telling a story with a smartphone. This practical and easy method doesn’t require showing people in the picture, allowing characters to be voiced. The video shows a driver picking up food at a local farm, delivering it to a restaurant, collecting food waste, and returning it to the farm as fertilizer. This reverse logistics service concept is complex even in its name, but LEGO Serious Play speeds up conversations, especially with people unfamiliar with such concepts.

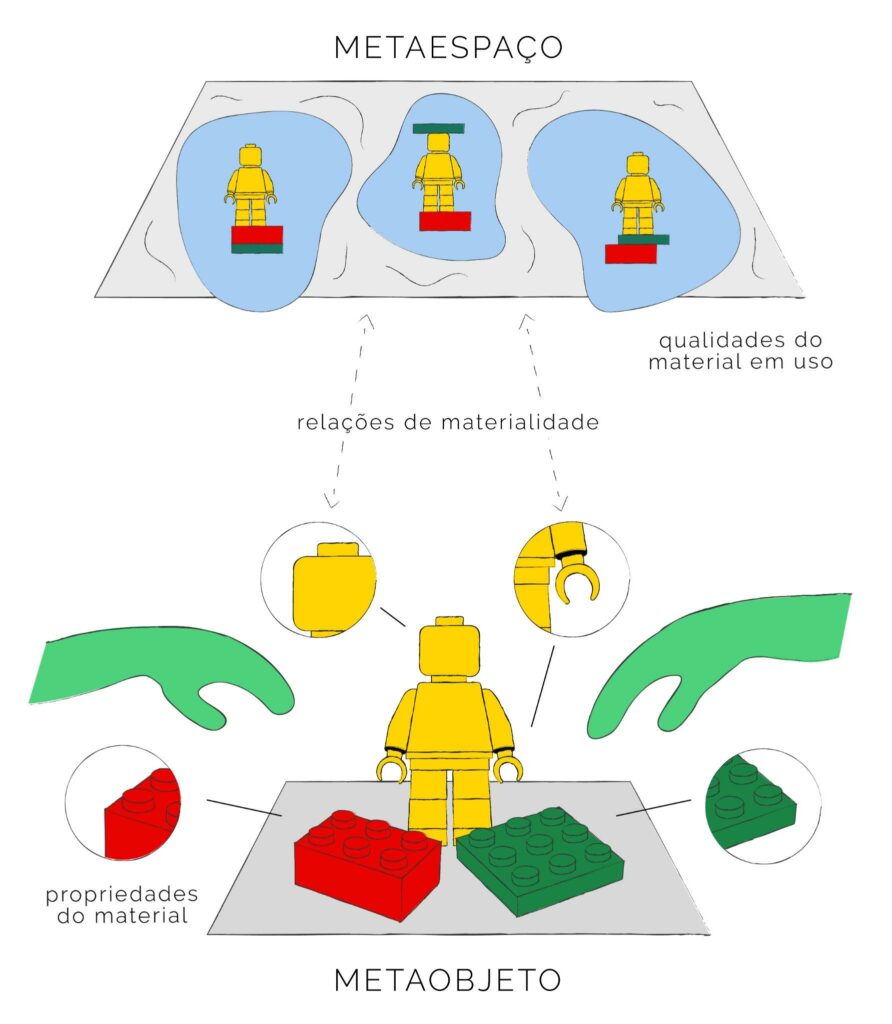

To theorize further, there is a complex theory about meta-design. A Brazilian researcher called Caio Vassão wrote about meta-design, defining a working object as a representation of an object coming into existence as a meta-object. This meta-object can be changed before it becomes real, representing and manipulating it instead of building the object right away. This is similar to sketching, modeling, or prototyping. With LEGO Serious Play, we build a metaphorical model useful in the early design phases, called the fuzzy front end of innovation. Manipulating a meta-object creates a meta-space, referring to the possibilities of the object’s form, structure, and function relationships.

In explaining the reverse logistics service, the main character uses the driver as a meta-object to tell the story, representing not just the driver or the car but the service being delivered. Service design is tricky because it involves human relationships, but LEGO Serious Play effectively represents these metaphorically. Meta-space represents these relationships and creates a context for the meta-object, in this case, the different points of interest on the road between the countryside and the urban environment where the restaurant is located.

This is the model that Larissa Paschoalin and I developed in 2021 to explain the physical, material, and relational properties that LEGO has, which enable the exploration of meta-spaces. Why is it so useful to use LEGO instead of other materials like Play-Doh or post-its? We could have used those materials, but they have biases due to their physical properties, dictating what you can and cannot do with them. We scrutinized and found that modularity, different colors, bright colors, and the simplicity of building and unbuilding, making and unmaking quickly with LEGO, are the reasons we exploit it so much. There are other reasons, which you can find in the published paper.

Imagine that farmers and restaurant owners in the previous example joined that particular co-design session. At that session, only design students or experts participated. The driver didn’t have a full-body person there to represent himself or herself. If we tried doing that, welcome to what I call participatory meta-design. This design includes the people being designed, so the community designs itself with their own hands.

This experience has been realized in many ways at the Laboratory of Design against Oppression, which stemmed from the first industrial design department outreach project mapping activity. In that activity, Marco Mazzaroto, Claudia Bordin, and I, the three founders of the Laboratory of Design Against Oppression, concluded that we had to unite our outreach projects under a single umbrella, which became known as LADO. Once we started having face-to-face activities, we began the process of community design using LEGO Serious Play. We built a huge metaphorical model to explore our dream for LADO. This activity was well-supported by one of our bright students, William Bizzotto dos Santos, who documented this process marvelously in his final work, published as a journal paper and conference paper.

The model had multiple aspects of the dream. It mapped the separation in Brazil between the “us” (leftists) and the “them” (rightists). We were concerned that rightists had to be engaged in these dialogues; otherwise, society would stay divided, and extreme far-right politics would win by fragmentation. Resisting Bolsonarism was our priority, and we also focused on liberating the oppressed, connecting the oppressed, developing critical consciousness, and talking to invisible people in society who support right-wing politicians. These people need to be aware of their alienation.

We developed many approaches for dreaming and re-dreaming our dreams. At LADO, dreaming was constant. We had a diverse chair project and a moment of reflection on what we were doing and our new dreams, symbolized by tying our dreams on the roof of our lab. Later, the dream fell on someone’s head by accident, and we had to re-dream it. Many things happened, but LEGO Serious Play was a spearhead of that process. At LADO, we don’t want to be like the oppressors. We approach ourselves and our visions of the future differently, with dreaming being crucial for that. Paulo Freire, an important Brazilian educator who inspired us, once said, “When education is not liberating, the dream of the oppressed is to become the oppressor.” We need more powerful dreams that are completely different from that.

We need practical experience designing with the oppressed, by the oppressed, for the oppressed. An example of using LEGO Serious Play in this context involves designing a community out of nothing on the outskirts of Curitiba. Curitiba had many violent slum removal actions, still ongoing, with rightists believing that people without a place to live should leave or be killed. These slums and occupations are just the result of the city attracting workers from afar without providing public housing solutions for them. The city made a poor design when they relocated people to the outskirts with improper infrastructure, poor bus routes, and self-sufficient community management.

We met some of these people from this community through LADO and a project called Uniperifa that connects universities with the periphery of Curitiba. They approached us for support in their co-design activity, using materials and approaches from the university. Our students also learned about community design in a harshly oppressed community. In 2022, we partnered and met the Condomínio Residencial Parque Iguaçú III community, starting with mapping the community meta-space, including physical appearance and social texture. We identified leaders, followers, relationships, and conflicts.

After cool explorations and discussions, we focused on how to engage the community in actions. The community was fragmented due to poor design by City Hall. They needed to nurture a new dream of being together. After theater-like experiences, we mapped actors in space, identified objects of dispute, and discussed problems like garbage piles and water contamination. We decided to focus on the community center, which was underused. The students and community members decided to renovate it, starting with painting. This successful community action started with LEGO Serious Play.

LEGO Serious Play is not just a meta-object because, in this case, people are committing to action, making it a shared object in the present. This insight stems from my PhD research on building hospitals, where contradictions in collaboration among stakeholders could lead to constructive or destructive outcomes. My thesis, “Expansive Design,” describes a constructive approach that welcomes contradictions. In the expansive hospital board game inspired by LEGO, players realized different design approaches. In a journal paper, we analyzed a team that managed a participatory design activity, engaging health practitioners and engineers to create a more synergetic hospital.

Making a shared object is not enough to foster a community. Community is about having a collective subject, a way of being together and acting in concert. People must understand that they are more than a sum of parts; they are a community. Sometimes, LEGO Serious Play and games like the Expansive Hospital can lead to competitive or individualistic outcomes due to inherent contradictions in capitalist society. In the game, financial incentives can lead to collaboration or self-interest, resulting in excitement and conflict. An example showed a team that played competitively, created a cartel, and caused the hospital to go bankrupt.

These contradictions are important to learn in design education. Our students at LADO have this experience, and we explore other methods beyond LEGO Serious Play. I particularly love Theater of the Oppressed dramatic games like the Circle of Knots, where participants untangle a human knot without releasing their hands, requiring coordination and movement. We also use colorful, multi-layered capes called Parangolés to celebrate Brazilian popular culture and express political concerns in design education. In 2019, our women students became hopeful about the future, giving a big hug and becoming one monstrous collective body, representing their majority in that class and hoping for a politically wise design future.

One example conducted online involved a workshop at a participatory design conference where participants designed a collective body. They represented themselves as one entity despite coming from different parts of the world. They used the pseudonym P.D. Commoners and created a collage on a mirror board, resulting in a chaotic and monstrous representation. This approach welcomed strong differences while creating unity.

To conclude, effective community design increases shared objectivity and subjectivity. It’s not just about great ideas, plans, or designs but having a stronger sense of the community’s reality and identity to transform that reality. That’s it for now. Thank you very much for watching up here.

References

Vassão, C. A. (2021). Metadesign: ferramentas, estratégias e ética para a complexidade. Editora Blucher.

Paschoalin, Larissa and Van Amstel, Frederick M.C. (2021). Materialidade no codesign: análise interacional de um experimento com blocos de montar (Codesign Materiality: interactional analysis of a building blocks experiment). Design e Tecnologia, 11(23). https://doi.org/10.23972/det2021iss23pp82-92

Bizotto dos Santos, W., Mazzarotto, M., & Van Amstel, F. (2024). Tomando um LADO: formação crítica e prática de liberdade no Laboratório de Design contra Opressões. Arcos Design, 17(1), 143–175. https://doi.org/10.12957/arcosdesign.2024.78425

Bizotto dos Santos, W.B., Mazzarotto, M.,and Van Amstel, F.(2023) Learning design as a human right: the beginnings of a design lab founded on critical pedagogy, in Derek Jones, Naz Borekci, Violeta Clemente, James Corazzo, Nicole Lotz, Liv Merete Nielsen, Lesley-Ann Noel (eds.), The 7th International Conference for Design Education Researchers, 29 November – 1 December 2023, London, United Kingdom. https://doi.org/10.21606/drslxd.2023.104

Amstel, F. M.C. van; Zerjav, V; Hartmann, T; Dewulf, G.P.M.R; Voort, M.C. van der. 2016. Expensive or expansive? Learning the value of boundary crossing in design projects. Engineering Project Organization Journal, 6 (1), Pages 15-29. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/21573727.2015.1117974

Angelon, Rafaela and Van Amstel, Frederick M.C. (2021) Monster aesthetics as an expression of decolonizing the design body. Art, Design & Communication in Higher Education, 20(1), pp. 83-102(20). https://doi.org/10.1386/adch_00031_1