Abstract: “Reading the world precedes reading the word,” says Paulo Freire, the Brazilian educator who revolutionized adult education. Instead of requiring students to read words without understanding their meanings, his educational approach, critical pedagogy, begins with reading the world through generative images that depict everyday scenes. Lego Serious Play can play a similar role in codesign by encoding the world in a physical metaphor that can be read and reread in many ways, working as a bridge between reading and writing words. For that, some methodological adaptations are necessary.

Lecture recorded in the Fall 2024 Research and Practice, MXD program.

Video

Audio

Full transcript

Today, I’m going to share a few thoughts about Paulo Freire’s text on the importance of reading and connect it with the practice of visualizing and manipulating ideas and concepts using Lego. We’re going to use this approach a lot in this studio, so you should know why I incorporate it so much. Before I dig into Lego Serious Play, I need to provide a bit of context about the text you just read. Paulo Freire was a Brazilian educator born in the Northeast of Brazil, a poor area with a high illiteracy rate, particularly during his time. Freire made adult education a means to transform reality. How many of you were familiar with Paulo Freire before reading this text? Please raise your hand. Okay, that’s great—you wrote about him. We’re going to read your article next week, by the way.

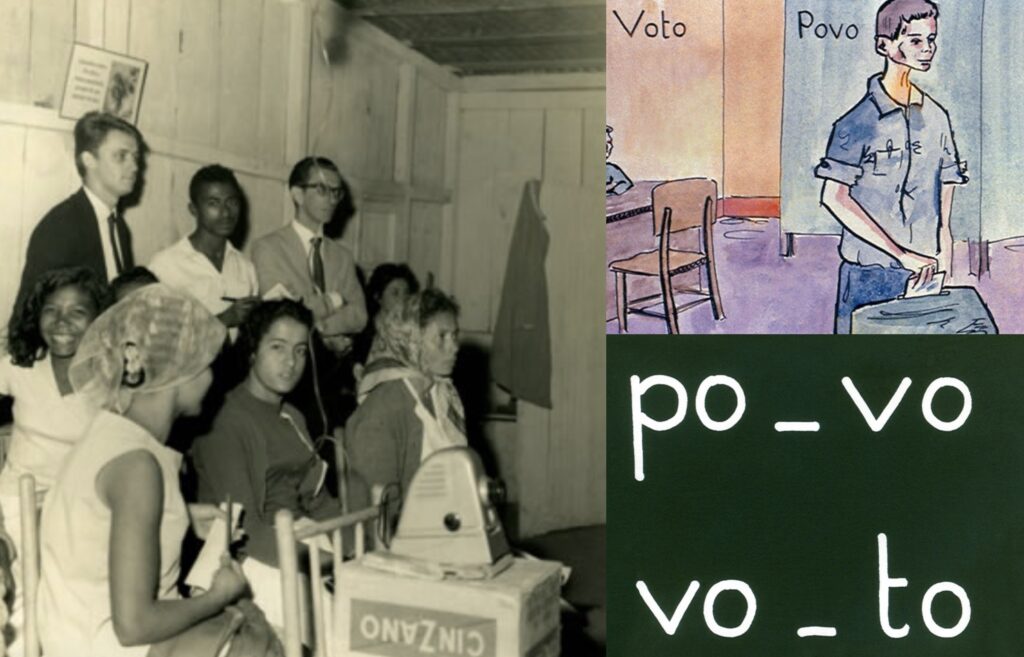

Freire is widely known in many countries, especially in the Global South, because his work is not only relevant to Brazil but to any situation where there are oppressed people. In his context, the oppressed were those living in rural areas or those who had recently moved to urban areas in Brazil and were illiterate. In the 1950s and 60s, 40% of Brazil’s population was illiterate, and there was a law preventing them from voting—if you couldn’t read and write, you couldn’t vote.

Paulo Freire wanted to change his world by changing its access to democracy. He believed that since these people couldn’t vote, politicians didn’t consider their best interests. He started by devising a local literacy program that later grew into a national initiative. The goal was to enable people who couldn’t read and write to achieve the minimum literacy required to vote. This led to the creation of what is now known as the Paulo Freire Method, although he didn’t give it that name himself. The method is based on three elements: visual codification, generative words, and dialogue.

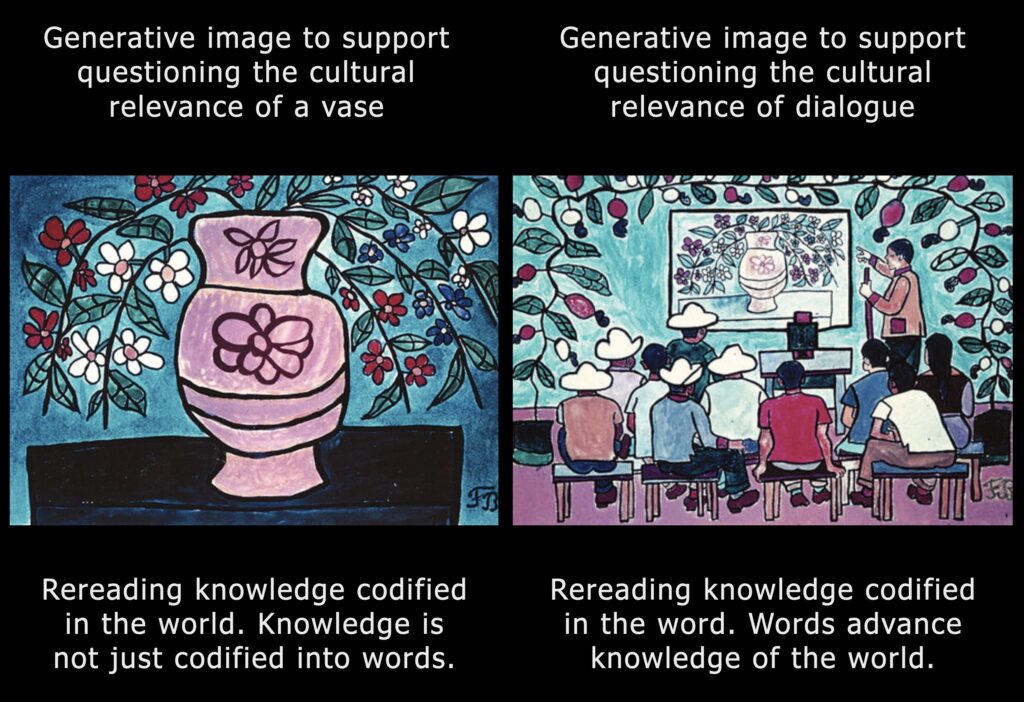

Visual codification involved artists working with Freire to create visuals that helped people understand concrete representations of the world before learning the word. The words were carefully chosen to provoke debate, hence the term “generative words.” For example, the word “voto” (vote) could spark discussions on its meaning, where some might see it as pointless while others view it as a symbol of hope. The third element, dialogue, was essential, as was participatory research.

To find words that could generate debate, a kind of ethnographic research was necessary. You had to immerse yourself in the world of the people you were educating and gather the words they used daily. For instance, “voto” is a common word in Brazil, but they also used “belota,” a very specific local word known only in certain regions. The reason for this is intricate, but in short, the images of concrete situations enabled people to reflect on their previous interpretations of the world before they learned to read the word. Freire always encouraged reading, re-reading, and reflecting, creating many layers of understanding.

Freire’s approach made people see themselves as part of the world, which meant they could change the world because they recognized it wasn’t fixed. If you see yourself as part of the world and you know you change, then the world itself can also change. This was operationalized in what Freire called the “circles of culture,” a key element of his literacy method. These circles are similar to what we’re doing here—discussing a text. However, for illiterate people, the discussion would start with images, not texts. These generative images sparked debates about the cultural relevance of the objects around them. Freire believed that if you could read these objects, you were already reading something.

The students in these programs weren’t like children learning what objects are—they were adults who knew a lot about the world but couldn’t operate with words. Making them confident that they could do that was essential. Instead of telling them they knew nothing, Freire started from what they already knew. A picture, something they recognized immediately, helped them realize they were already “reading” the world.

There’s something very design-like about this approach. Think about how much knowledge we, as designers, put into the world—not through words, but through coded knowledge. Even when we use typography in our graphic designs, we aren’t always using it as text—sometimes, it’s an image. We are coding knowledge into the world, and people read that knowledge. Re-reading means seeing something from a different perspective.

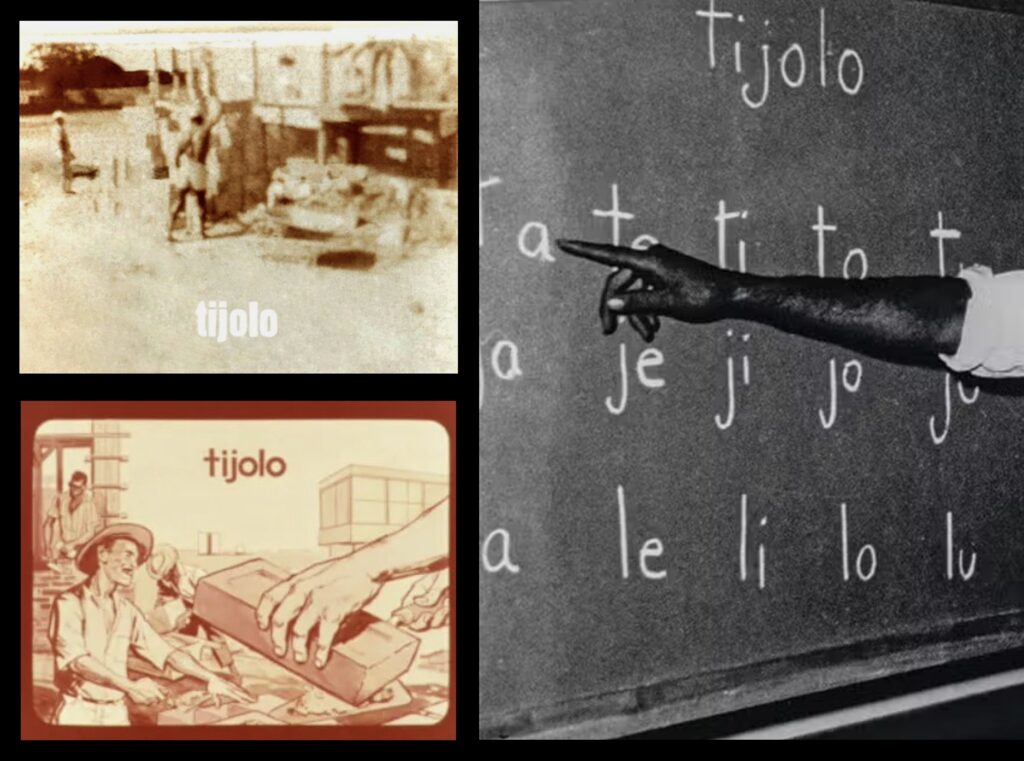

Freire’s next step was to introduce the word with a generative image in the background. For instance, the word “Tijolo” (brick) would be introduced with an image of someone making or using a brick. In Brasília, a modern city being built at the time, this image made sense. But in the Northeast, where they made bricks by hand, the same image had a different meaning. Freire used images relevant to localities, understanding that Brazil is a huge country with diverse experiences. After introducing the word, it would be broken down into syllables, with each syllable generating new variations. For example, the syllable “ta” could lead to “ti” or “li.” Students wouldn’t learn all the words in alphabetical order but rather use the parts of the word they had already learned to create new knowledge. The idea was to gain as much knowledge as possible with the least effort initially, allowing them to appropriate new things gradually.

Through this method, Freire and his collaborators helped 300 rural workers in the town of Angicos learn to read and write in just 40 contact hours—an impressive achievement that attracted attention both in and outside Brazil. The prospects in that town’s elections completely changed as a result.

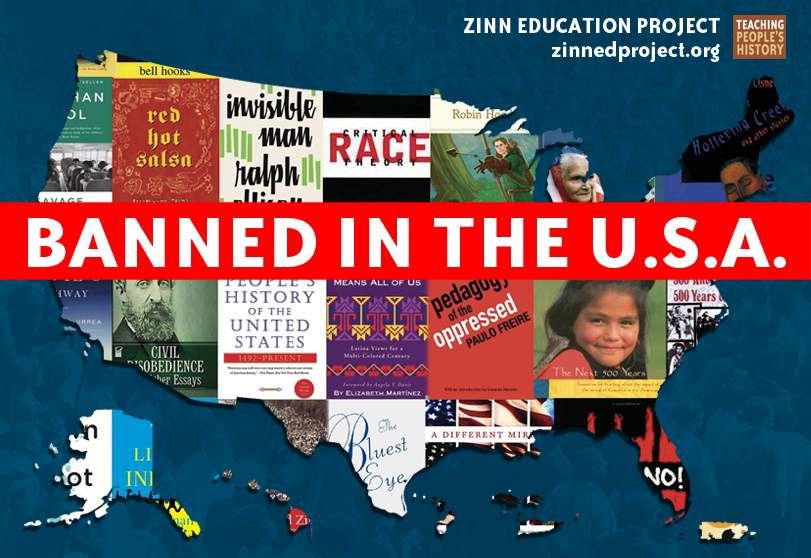

When Paulo Freire started working on a national program that aimed to change Brazil, a coup d’état occurred. The government in Brazil was overthrown, democracy ended, and the military took over the country for almost 20 years. Freire was immediately persecuted, imprisoned, and eventually had to go into exile. He lived in many countries, including the U.S., where many people became familiar with his work. “Pedagogy of the Oppressed,” his most famous book, was widely read in the U.S. However, it has also been banned in some places, like Arizona, where it was considered inappropriate for public school students because some viewed it as leftist indoctrination. Although it’s no longer banned in Arizona, this reflects the controversial nature of Freire’s work.

Understanding this political scenario and the relevance of Paulo Freire in similar situations, such as Brazil under Bolsonaro’s rule in 2020, we founded the Design and Oppression Network. Together with other researchers in Brazil, we explored the connection between Freire’s ideas and design. We held numerous online reading groups and other activities, focusing on how to read and rewrite the design world we live in.

My particular interest was in using Lego because I had previously used it for co-designing with users. For example, the people in this picture are redesigning the visual system of their solidarity entrepreneurship—a small business producing local food and other goods. Lego was essential for them to learn how to deal with graphic and conceptual representations of their business.

From my experiments with Lego, I learned that co-designers can read and write the world as if it were a system. They see the world as interconnected elements, which, while a simplification, gives a big-picture view. Lego, as a microcosm of the modern world, represents mass-produced objects that can be combined and recombined in various designs. It is a cornerstone representation of what design is in our society, particularly in U.S. society.

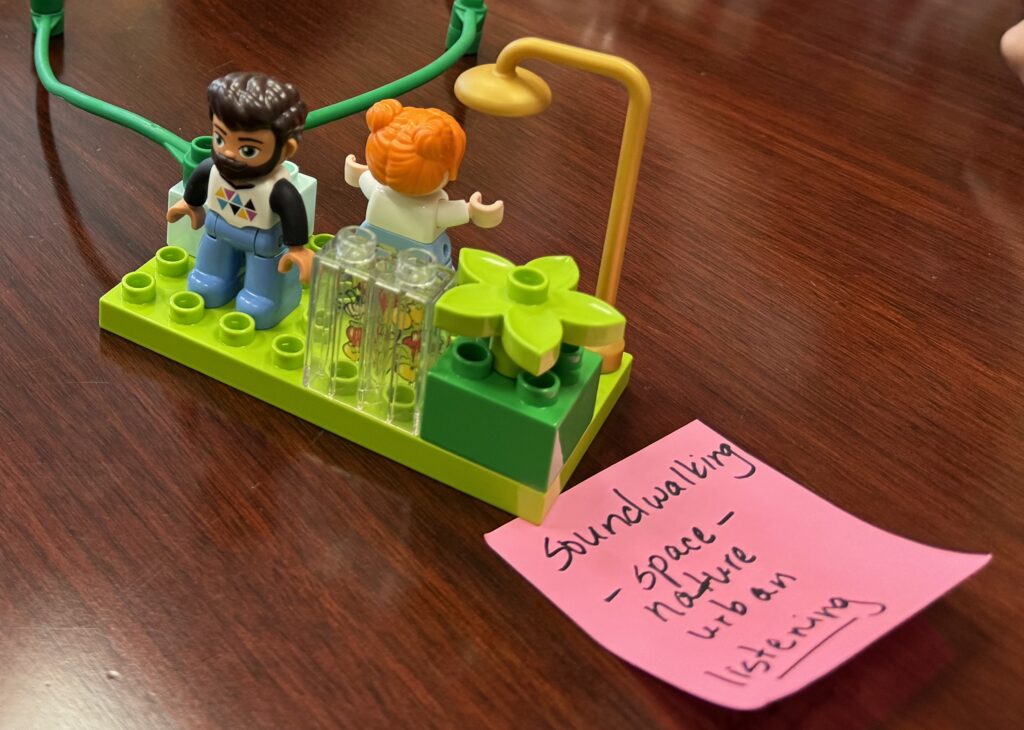

The Lego Serious Play method extends the use of Lego for business, education, and learning. It allows the block system to represent abstract systems, not just physical ones. For example, I used it in a project with Aliança para Mobilidade Popular, a group promoting bicycle use in Curitiba, and a recent workshop mapping outreach projects at the U.S. College of the Arts. Lego Serious Play relies on physical metaphors—two blocks can represent an airplane, and if you push the metaphor further, they can symbolize speed or international relationships. By relating different bricks, you create complex metaphors useful for naming aspects of the world we don’t have words for yet. First, you name it using Lego; later, you name it with words, creating a bridge between what you know and what you need to learn.

After naming the world with a metaphorical model, words are cognitively extracted from the model. Although I could have asked participants directly, “What is your outreach project? Just write it down,” I found that starting with Lego helps people understand the world before expressing it in words. People often know something but struggle to express it. Spending time with Lego before writing down the words aids in understanding. It’s tricky—you know the world, but not the word. Using a concrete representation of the world, like a generative image, bridges that gap.

Paulo Freire emphasized learning the word to change the world, a theme in his “Pedagogy of the Oppressed,” which is distinct from “The Importance of the Act of Reading” we just discussed. In “Pedagogy of the Oppressed,” Freire is more philosophical, stating, “To exist humanly is to name the world, to change it. Once named, the world reappears to the namers as a problem, requiring a new naming.” This means the world is constantly changing, and as part of it, we must continually rename it as new challenges arise. This process expands our perception of the world.

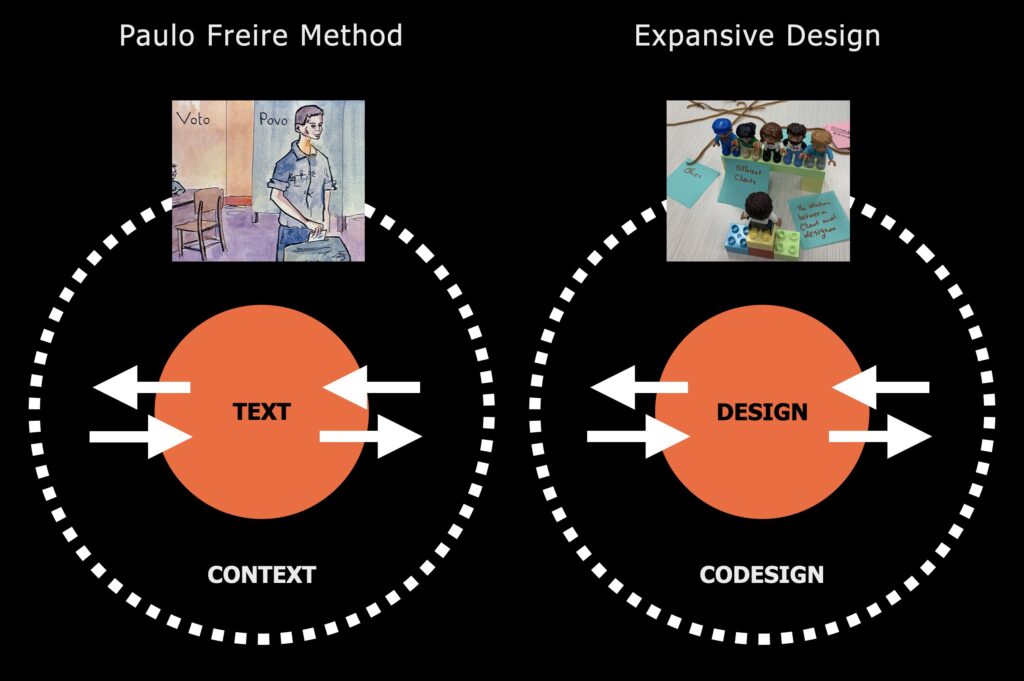

Freire also said, “The understanding attained by critical reading of a text implies perceiving the relationship between text and context.” I emphasize the importance of taking notes so you can easily recall specific parts of a text. This back-and-forth movement between reading the text and its context is a graphical representation of the Paulo Freire method.

Sometimes, images serve as a bridge between text and context, similar to what I did in Expansive Design—my PhD thesis. Expansive Design uses different representations of contradictions, like Lego Serious Play, games, and theater, to explore the differences between design and co-design. For me, codesign is equivalent to context, though I prefer not to refer to the design as text because this would reduce design to language. Design is co-designed through languages but also non-linguistic elements. That is why I use the term codesign instead of context to talk about what is around design. Codesign is not an element of Expansive Design; it’s an inherent part of the world. Many people are already codesigning their world every design, even if unaware.

One way to raise awareness of codesign is using generative image in card decks. For example, my students in Brazil designed a card deck representing the existential crises that design students typically face. We used it here last spring. After choosing a crisis they were facing, students represented it using Lego Serious Play. Then, they could realize their crises were socially shared and codesigned around their existence.

In this example, the author of the model isn’t present now. Still, the model allowed them to express something difficult to articulate otherwise—like the challenge of breaking free from a protective bubble to interact with people from diverse backgrounds. This model, which might be hard to interpret without the session’s audio recording, represents that struggle.

In the early stages of a project, it’s easier and quicker to codesign with Lego than with other materials. While some may prefer post-its, sketchbooks, or computers, this is usually because they have more experience with those tools. Even people who have never used Lego before find it easier to express themselves with it, especially with Lego Duplo, designed for young children to be simple to handle. This diverges from the traditional Lego Serious Play model that uses finer, more detailed Lego pieces. I use Duplo to include people who might have difficulty with the more complex pieces or didn’t have much Lego experience in their childhood.

Another addition to my method is recording the model presentation on the author’s smartphone. This allows the person to revisit and reflect on the model later. I don’t record it on my phone; instead, I ask, “Who’s going to record this?” because if you record it, you’re the one who will reread it, not me. This approach promotes learning among yourselves. One example is Hien Fan, a third-year researcher in the MXD program, who has been using this method extensively. She has created many models, and by revisiting her past classes, I’ve seen how her research focus has evolved over time. Her first model, built in February, was about moving between different contexts. Now, in August, she is studying the contradiction of diversity in design education. Over a few months, her understanding of the world has completely changed, but the world itself was always there. She was just searching for the right words to express it. Once she found those words, her ability to address the contradiction became stronger, allowing her to develop a more critical consciousness.

Hien didn’t just use Lego Serious Play in my classes; she also applied it in her research with other students, interviewing them about their experiences in the MXD program and asking them to build Lego models. She also uses this method in our advisory meetings and her undergraduate teaching activities. I’m sharing this because you might also want to use these materials—they’re available. We have two boxes in this studio, and you can also use them in room FAC 310 if you want to experiment with your undergrad students.

Finally, I’ve discovered that Lego Serious Play models are generative objects, much like generative images and words. They are objects that generate other objects. You can use Lego Serious Play to design new objects in a dialogical making activity. However, Lego Serious Play only works effectively if you’re engaging with others—it’s not very powerful if you’re alone. The more people involved, the richer the diversity of viewpoints.

In conclusion, combining critical pedagogy with Lego Serious Play can help avoid becoming “another brick in the wall” like in Pink Floyd’s song. You remain a brick, but a special one that enables students to reread their world and understand what it means to be a brick. You can question the framework that confines the brick and perhaps even build something other than a wall. If you’re interested in digging deeper into these topics, “Pedagogy of the Oppressed” is a must-read for understanding the underlying concepts.

References

Freire, P. (1983). The importance of the act of reading. Journal of education, 165(1), 5-11.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum, New York.

Van Amstel, F., Sâmia, B., Serpa, B.O., Marco, M., Carvalho, R.A.,and Gonzatto, R.F.(2021) Insurgent Design Coalitions: The history of the Design & Oppression network, in Leitão, R.M., Men, I., Noel, L-A., Lima, J., Meninato, T. (eds.), Pivot 2021: Dismantling/Reassembling, 22-23 July, Toronto, Canada. https://doi.org/10.21606/pluriversal.2021.0018

Roos, J., & Victor, B. (2018). How it all began: the origins of LEGO® Serious Play®. International Journal of Management and Applied Research, 5(4), 326-343.

Floyd, P. (1979). Another brick in the wall. The Wall.