The way Facebook conceals or shows up messages in the news feed is a mystery to most users. Facebook gives the impression that if a user posts a status update, all of her friends receive it in the timeline, but that is not always true. The Edgerank algorithm decides what is shown in the timeline based on three variables:

- Affinity: the interaction rate between the person who posted ant the person who receives it.

- Weight: the relevance of what is being posted based on the content type (picture or text) and the interactions gathered around (likes and comments).

- Decay: the content’s age. The oldest, the smaller the score.

This abstract description does little to understand the Edgerank algorithm’s consequences in forming social groups. For example, when someone likes content only from right-wing friends, she might receive less content from left-wing friends. This is what Eli Parisier calls a filter bubble.

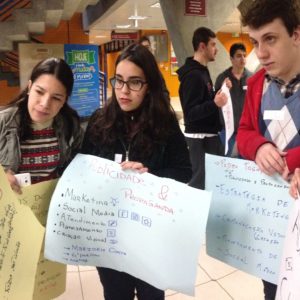

To discuss the impact of Edgerank in forming political groups, I proposed an analog game to be played at the Brazilian Free Software Forum. The Social Participation Lab organized public experiments about current and future social participation technology. Facebook is the most used channel by Brazilian politicians to interact with their electorate and perhaps also the main channel for citizens to discuss politics with each other. The goal of the public experiment was to make explicit Facebook’s mediation of the political debate.

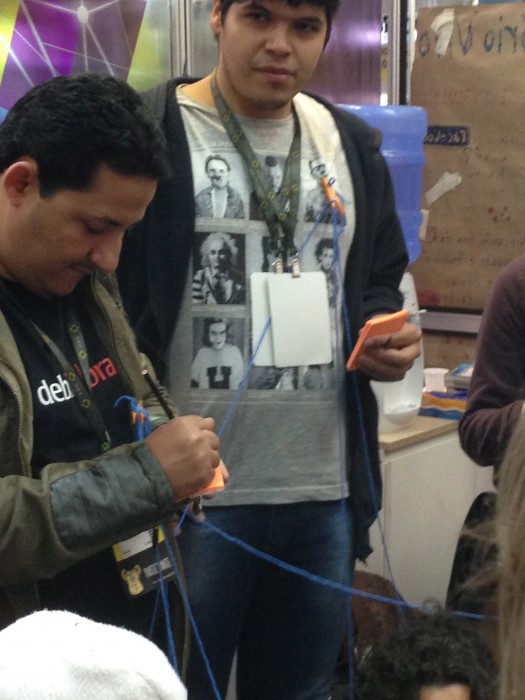

The game uses pen, paper notes, stickers, and yarn to simulate the impact of Facebook’s algorithm in distributing messages across users’ timelines. The basic mechanic consists of sharing updates on paper notes with others connected by a wool thread (a friendship connection). Every player has a set of like and dislike stickers to put on updates from other players.

When an update is received, the player may choose to either put a sticker on it (the equivalent of a like or dislike button) and forward it to another friend or return it to the giver. When the update reaches its author, it cannot be distributed any longer, but if everybody likes the update, it circulates across the network.

The winner is the message’s author with the highest number of likes and dislikes stickers. After declaring the winner and digesting the messages, the players usually understand that the most popular was the most divisive argument (with an almost equal number of likes and dislikes).

In the experiment at the Free Software Forum we asked players to post updates about the reduction of the penal age, a constitutional change currently being discussed by the Brazilian Congress. The updates that got the most likes were the ones in favor of penal age reduction, but there were more updates against the penal age reduction. The popular updates circulated so much that, at some point, nobody knew who was the original author and could not return the update to him or her. This was considered analogous to viral spread.

We could also observe changes in friendship. If a player had all his updates rejected by a friend, he would not try sending more updates to him. In contrast, a player who liked everything had more chances to make new friends and spread his updates. Not surprisingly, the winner was the one who gave all his like stickers at the beginning of the game.

After playing, we held a debate about the algorithm. The participants were surprised to know how quickly they can be isolated into bubbles if they are consistent in their behavior. They learned that if they want to be aware of what others are thinking, they need to like content they do not like. Otherwise, the algorithm does not show them any longer. This somewhat counter-intuitive behavior is the only way to prevent being isolated from people of the same opinion on Facebook.

The Conceal and Show Game has demonstrated a promising approach for bringing the controversy around social network algorithms to the public. We expect the game also to help design algorithms that prevent people from isolation.

References

Van Amstel, Frederick M.C and Gonzatto, Rodrigo Freese. (2020) The Anthropophagic Studio: Towards a Critical Pedagogy for Interaction Design. Digital Creativity, 31(4), p. 259-283. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/14626268.2020.1802295