This is a book summary for the Pluriversal Design Book Club. It is a short contextualized introduction to Paulo Freire’s magnum opus. The main feature of this introduction is a visual scheme to frame the historical-dialectical relationships developed throughout the book: oppression, banking education, and colonization. This scheme also considers the emergence of third forces from contradictions. In this case, liberation, critical pedagogy, and cultural synthesis.

This book inspired Participatory Design pioneers in the 1970s and continues to be an inspiring reading for young design students of today. That is probably because this book frames participation as a means to fight oppression rather than merely reaching a consensus, being creative, or having fun. It provides a clear political agenda for Participatory Design: expanding democracy to include the historically excluded from design processes. What comes from this agenda is always full of activist energy.

Audio

Video

Full transcript

This is not a translation or a literal summary of what is written in the book. I will try to convey the main concepts I find interesting in the book. I might run into some oversimplifications or extrapolations based on my reading, but we can address issues like that during the discussion session after my presentation.

Let me start by providing some context for where this book was written. Paulo Freire developed a literacy method for education in a country that, between the 1950s and 1960s, had more than 70% of illiterate people. Politicians exploited this situation to buy votes and deceive people, which is why they opposed extending education to the masses. Once the military government stabilized in Brazil in 1964, Paulo Freire was persecuted and imprisoned. In 1968, while in political exile in Chile, he wrote Pedagogy of the Oppressed.

Freire firmly believed that education was key to denouncing and fighting oppression. He saw how people who acquired literacy in a very short time, such as in the 40-hour Angicos experiment in a small city in Northeast Brazil, became empowered citizens, equipped with the knowledge to avoid being deceived by oppressors. They could engage more consciously with their lives and develop their livelihoods.

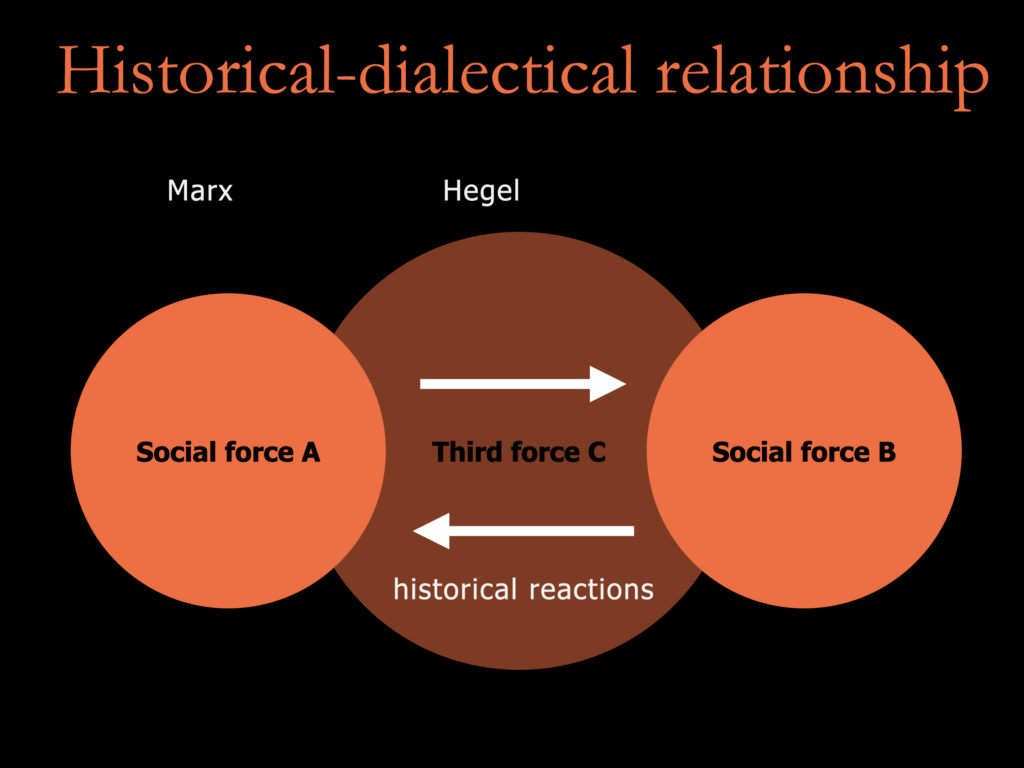

The basic concept behind the Pedagogy of the Oppressed and the notion of oppression is the historical dialectical relationship that Freire draws from Marx and especially Hegel. Hegel wrote about the master-slave dialectic, and Marx extended this through a historical perspective when he spoke about the struggle between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. Freire frequently referred to this, and I will present the major dialectical relationships as I read them in his book. While Freire may not always present them in the same schematic way I’ll do here, my goal is to simplify these ideas to help you engage in a meaningful conversation.

This relationship is composed of three elements: a social force (A), its opposite social force (B), and a third force (C) that may or may not emerge from the struggle between these two forces. These forces do not just interact abstractly but engage in historical actions.

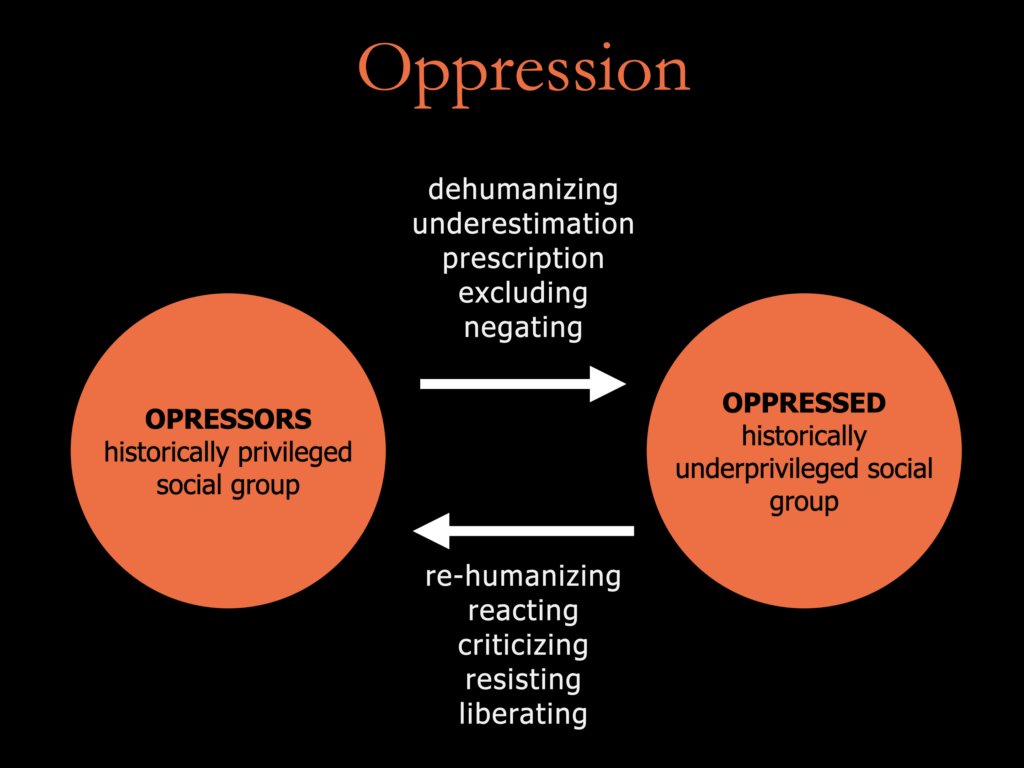

Let me apply this abstract model to a concrete situation—oppression, the basic historical dialectical relationship Freire examines in this book.

Freire posits that the world is divided into two social groups: one historically privileged and the other historically underprivileged. The oppressors try to dehumanize, underestimate, prescribe behavior, and exclude the oppressed, denying them the possibility of being fully human. They claim that the oppressed are incapable and should not be treated as full human beings. However, the oppressed react to this oppression by organizing, resisting, and seeking their own liberation. In doing so, they also liberate the oppressors from this relationship, which prevents the oppressors from fully developing as humans. Although the oppressors believe they are in power, they, too, are not developing ethically or as complete human beings.

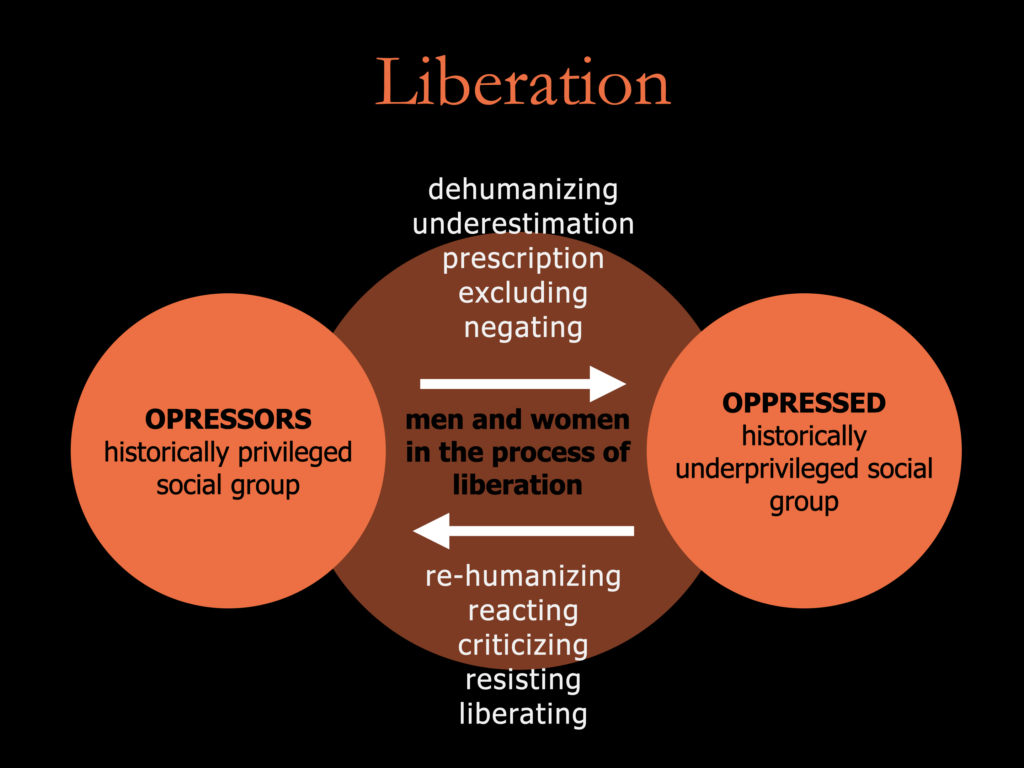

Freire also suggests a third possibility: that when the oppressed engage in liberating actions against the oppressors, they may create a new kind of person, neither oppressor nor oppressed—a person in the process of liberation. This is the third force that Freire seeks to support with the Pedagogy of the Oppressed.

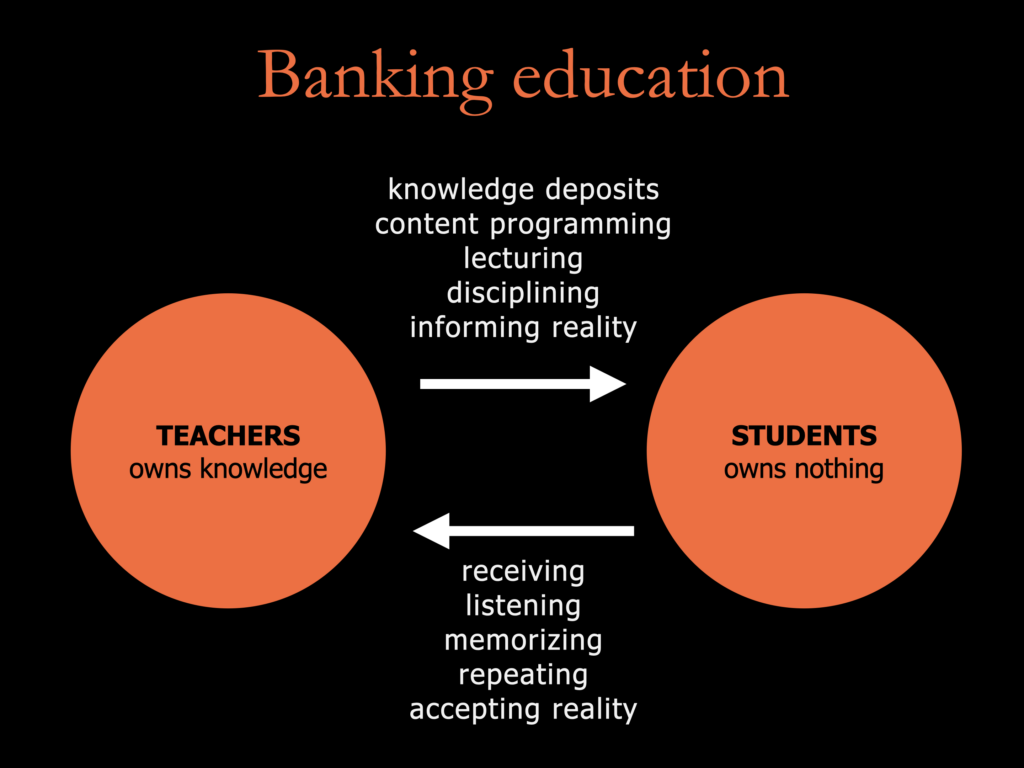

Freire goes on to analyze “banking education,” a specific form of oppression manifesting in education. He argues that this method of education is historically how oppression is maintained in society, which is why he denounces it. In banking education, knowledge is treated as a deposit that teachers make into the “empty” minds of students, who are expected to receive, memorize, repeat, and accept reality as it is without the opportunity to transform it.

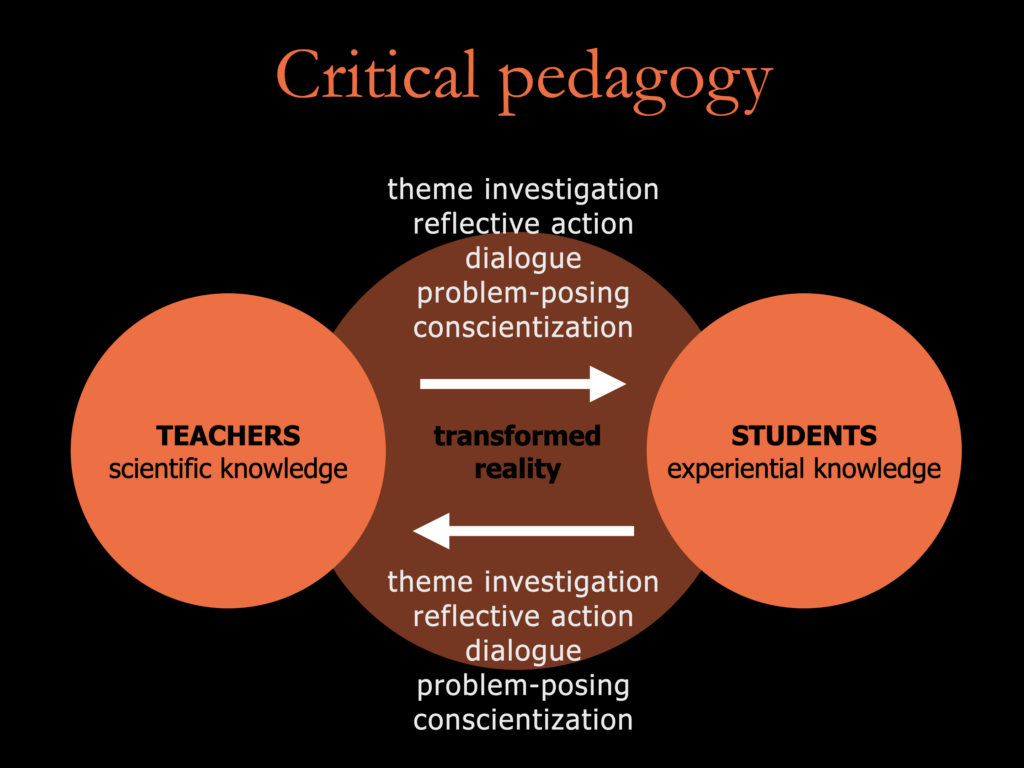

Freire and his colleagues, particularly in Angicos, developed a new approach to education, which he initially called Pedagogy of the Oppressed but is now more widely known as Critical Pedagogy. This approach emphasizes the importance of understanding students’ existing knowledge and experiences as a starting point for education. It involves investigating themes that meaningfully engage students with their reality, leading to participatory action research and design.

Freire argues that teachers and students should engage in a participatory, co-investigative process, reflecting on their actions and engaging in meaningful dialogue. This approach, known as problem-posing education, aims at conscientization. Although this word doesn’t exist in English, I believe it’s important to translate it as such. Some people prefer to keep the original Portuguese word conscientização unstranslated. We have many English neologisms in Portuguese. Why not have an English neologism from a Portuguese word? I mind translating it this way.

Coming back to the process, teachers and students are engaging in essentially the same kind of activity. There’s no asymmetry between the actions of one social group and the other because the goal is to focus on the same object, which is reality and the world around the students. Transforming that reality is the outcome of critical pedagogy.

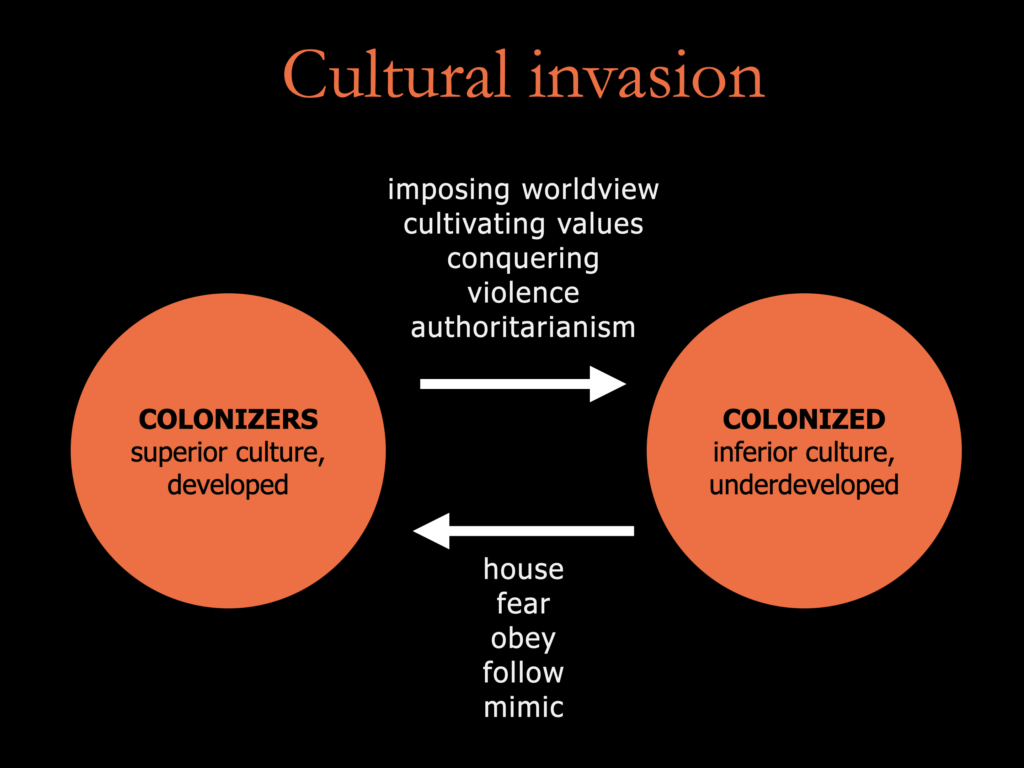

But this goes much further because Paulo Freire isn’t just looking at education; he’s viewing education as a means for something much broader: fighting against another form of oppression, which he doesn’t directly name, but later readers and commentators have identified as colonization. Therefore, Freire is also considered one of the authors related to decolonizing, post-colonial, and other movements. Freire calls this “cultural invasion.”

Cultural invasion is a kind of imposing a worldview from one superior culture onto an inferior culture. The superior culture is seen as fully developed and the best, while the inferior culture, the undeveloped world, is seen as lesser. Therefore, the first world must invade the third world and colonize it because that’s the way the colonized can develop. However, we know, and Freire also acknowledges, that colonizers and oppressors take advantage of this colonization, leaving very little for the colonized. It’s an unbalanced relationship, as you can see from their actions. The colonizers impose their worldview, cultivate values, conquer, and are often violent and authoritarian. The colonized, on the other hand, are forced to house the oppressors

Freire presents an interesting understanding of colonization. The colonized have the colonizer within themselves, influencing their behavior from the inside. The colonized fear, obey, follow, and even mimic the colonizer, aspiring to become like them. This dynamic has been analyzed by other authors. Still, in this book, Freire uses the concept of cultural invasion to build up cultural synthesis, which is his broader proposal for education. He argues that no revolution can break free from colonization without developing some form of critical pedagogy.

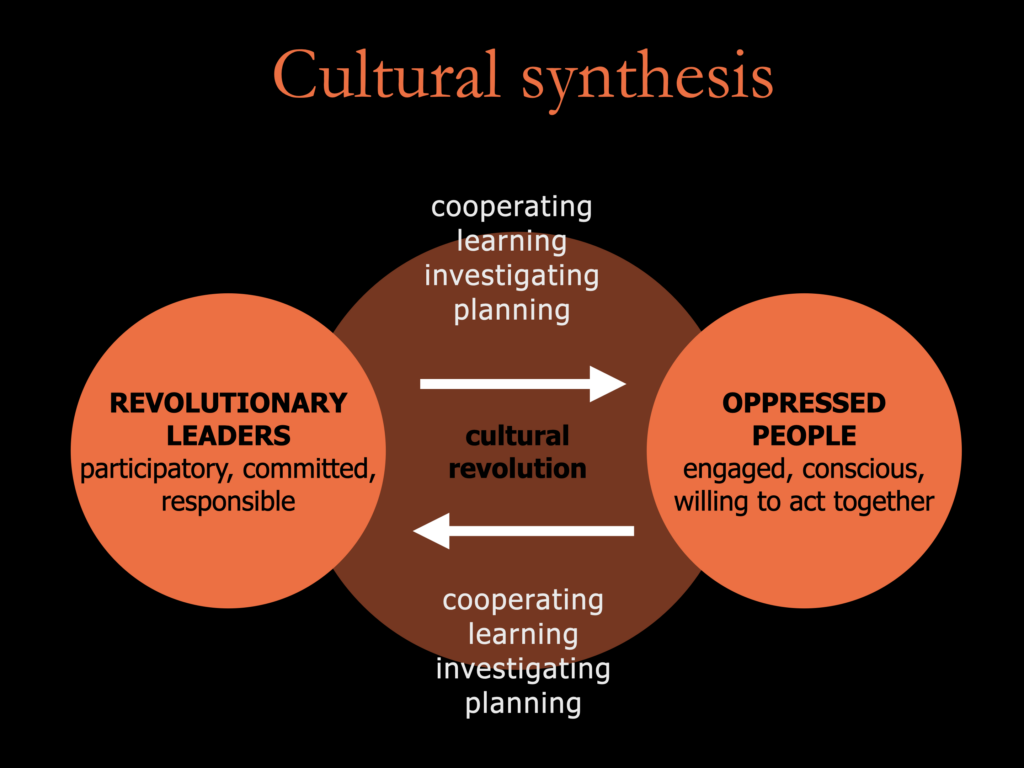

In the last chapter of this book, Freire addresses revolutionary leaders—people who engage in decolonizing struggles, even wars, although he doesn’t directly mention them. The context of the time was the revolutionary wars occurring throughout Latin America. Revolutionary leaders, typically from the oppressor group, are usually privileged people who recognize the significant social injustices and want to fight against them. They either join the oppressed people or remain in a triangle relationship where they are neither oppressors nor oppressed. Freire doesn’t explain this part in detail, but revolutionary leaders are committed to the oppressed liberation. They cooperate, learn from the oppressed, investigate their reality, and explore ways to overcome oppression, planning together for a new society.

The relationship between revolutionary leaders and oppressed people aims to cooperate and bring about a cultural revolution. Freire mentions Mao Zedong and the Chinese revolution—though not directly, you can infer that he envisions a cultural revolution in Latin America, with critical pedagogy as a fundamental methodology for that. He also implies that the cultural revolution in China and other places wasn’t as successful due to the lack of a revolutionary education pedagogy. Freire firmly believed that the oppressed could make history, not just understand and learn it.

When Freire talks about the oppressed in this book, he refers to the peasants in Latin America. His experience with the Angicos City experiment in the 1960s, conducted in a peasant community, informed much of his thinking. Later, after he had to leave Brazil due to the political situation, Freire joined revolutionary forces in Chile and helped educate peasants there. They tried to follow the model pioneered by Che Guevara in Cuba, focusing on rural areas to convince peasants of their oppression and motivate them to take action. This strategy contributed to the strengthening of the Cuban revolution and was effective in various parts of Latin America, although it didn’t work everywhere. In Brazil, the Landless Workers’ Movement (MST) still remains a strong social and political force as of today.

To summarize the “Pedagogy of the Oppressed” in one sentence: “it is a pedagogy that must be forged with, not for, the oppressed” (Freire, 2005, p.48)—whether individuals or groups—in their incessant struggle to regain their humanity. It is a revolutionary approach to education.

Now, I’ll give you a brief glimpse into the elements of what is known as the Paulo Freire method. Although Freire didn’t label it a “method” and didn’t like prescriptive approaches, some people have translated his ideas into a more structured educational approach. The main elements are cultural circles and thematic investigation.

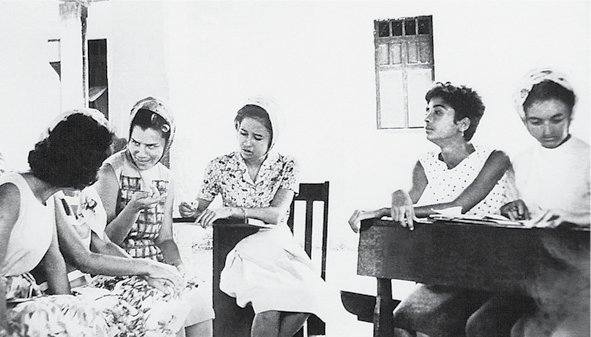

A cultural circle is a group of people from a localized community who come together to learn and transform their cultural reality. It’s not like a traditional classroom that follows a set curriculum. Instead, it focuses on the real-life struggles and issues people face, brought into discussion through participatory research in which the students participate. They go into the community, walk around, take notes, and talk to people to understand the thematic universe and specifically identify “limit situations”—moments when societal contradictions are most pronounced and oppression is acute, making it easier to understand and distinguish. This becomes a “generative theme,” a theme brought to discussion to generate further discussions and more themes—hence the term “generative theme.”

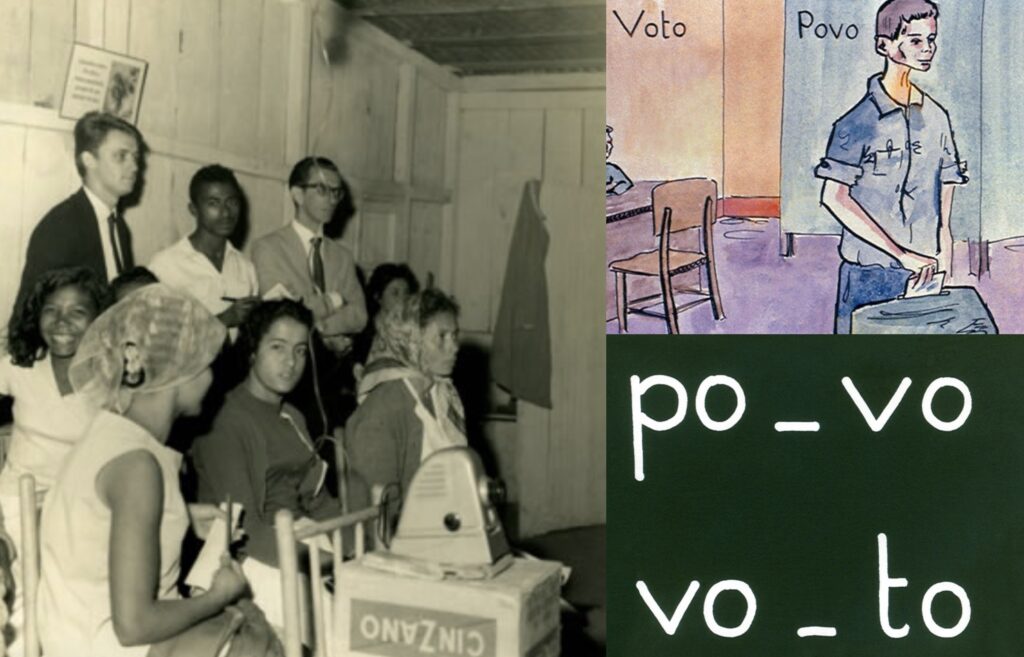

Here’s an example of how a generative theme is coded using simple language: the two slides on the right are shown to students using a slide projector. You can see a clear connection to design, although Freire doesn’t use that word directly. These limit-situations are coded in a way that illiterate people can understand, leading to meaningful conversations. Freire and his colleagues used advanced technology for their time—slide projections—to present images of familiar but specific situations in people’s lives, such as voting in a rigged political system. Even in poor villages, some without electricity, these images were projected onto walls to spark discussion. For instance, Freire would teach people to read words like “voto” (vote) and “povo” (people), then ask critical questions like, “Can voting really change this society?” He encouraged people to think critically about the contradictions between voting and the reality of political corruption.

Freire wrote extensively, but not all his works have been translated into English. Unfortunately, the design field doesn’t often reference his other works besides Pedagogy of the Oppressed, so I’ve included a slide with three of his major works that I highly recommend. These books offer a better understanding of Freire’s thinking related to design. Pedagogy of the Oppressed is a book about possible revolutions in Latin America and other parts of the world in the 1970s. If you don’t believe they are still possible, then it might be hard to connect. The other three books are less aggressive in language and more relevant to contemporary issues. Pedagogy of Freedom, particularly, is highly relevant to our current times, as it was written in the 1990s. It offers fascinating insights and connections to our present situation. I strongly encourage you to explore Paulo Freire more. That’s it. I apologize if I’ve oversimplified any of these concepts. Thank you for listening.