Quest 1 course (open to all majors), School of Art + Art History, University of Florida, 45 hours, Spring 2025

This course asks: How does design work as a tool for shaping, understanding, and communicating identity—“the fact of being who or what a person is”—in everyday life? Designed environments, objects, and interfaces allow us to shape the “facts” of how we see ourselves and others. Today, design organizes how we navigate public spaces and digital environments, impacts the way we understand everything from our political positions to our brand preferences, and positions us within both our local communities and the global commodities marketplace. Specific places, times, and cultures influence how humans understand and use design, and knowledge of these environmental contexts allows us to recognize our own context(s) as particular rather than universal. With a diverse and global range of design artifacts as our case studies, we’ll interrogate issues related to form (the visual and physical qualities of design), function (what design is used for, and how), and philosophy (the underlying conceptual and ethical frameworks that inform the design process). Readings, viewings, discussions, critical making activities, and design-thinking exercises provide a shared framework for investigation. Through these, we’ll seek to understand the interactions between design and identity in order to become more informed and empowered makers and users of design.

Learning experience

This Quest course immerses students in an embodied and reflective exploration of design and identity in everyday life. This exploration consists mainly of observing and sketching things and places in visual diaries, actively engaging in dialogical culture circles, and critically analyzing real-world designs encountered in students’ environments. Participating in these activities encourages students to slow down, pay close attention to their surroundings, and physically engage with the design elements that structure their daily lives. This approach prioritizes reading worlds over reading words. However, selected academic texts, documentaries, and podcasts are prescribed as a means to expand reading the world. Self-reflection is at the heart of the course. The sustained practice of documenting and analyzing observations in visual diaries, sharing insights during culture circles, and synthesizing learning into a visual essay puts self-reflection into practice. Through these embodied and reflective practices, students develop a nuanced understanding of design’s role in everyday life and their capacity to engage critically and creatively with it to shape their identities, individually and collectively, as part of a world of many worlds. As a side effect of this course, students will have an overview of the Design Studies field and a selected range of practical design skills they may develop: observation, visualization, problematization, and dialogue.

Assignments

1) Dialogical participation

In this course, each in-person session will include a culture circle—a participatory space inspired by Paulo Freire’s pedagogy, designed to foster dialogue and critical reflection. These culture circles will allow students to discuss their observations of design in everyday life, drawing from their visual diaries and engaging with their peers in small and larger group discussions. The goal is to collaboratively explore design’s visible and invisible dimensions, enriching our understanding of its role in shaping culture, identity, and society. Dialogue is fundamental to understanding the interplay between design and identity in everyday life because these phenomena are inherently relational and contextual. To receive a full grade for this assignment, students must:

- Bring their visual diaries to class

- Share their observations

- Express their views in a democratic manner

- Ask thoughtful questions

- Actively listen while others are speaking

Students who miss an in-person session can still get the dialogical participation grade if they submit a conversation history with 20 prompts minimum with ChatGPT or NaviGator Chat about the session theme. The first prompt should either upload the reading files or copy and paste some articles content so that the artificial intelligence learn about what you are going to discuss.

Both in-person and virtual dialogical participation must respect the following UF Policies (see their definitions below): Generative Artificial Intelligence, Academic Freedom and Responsibility, Academic integrity, Academic honesty, Disruptive behavior, Non-Discrimination Policy, Title IX, In Class Recording, and others that apply.

2) Visual diary

The visual diary is a key physical (not digital) tool in this course, designed to help students hone their observational skills by documenting the role of design in everyday life. This assignment focuses not on the technical quality or aesthetic beauty of the sketches, but on the depth and thoughtfulness of their observations. The purpose is to cultivate an ability to see and analyze the often-overlooked ways in which design shapes identity, culture, and daily interactions.

Students will use their visual diaries to capture instances of design they encounter—objects, spaces, systems, and interactions—through sketches, notes, and reflections. These sketches, better framed as tools for framing and recording observations, serve as a medium for exploring the relationships between design and identity. No previous drawing skills are required, as the emphasis is on what is observed and interpreted, not how it is drawn. The visual diary is meant to encourage critical engagement with the designed world, helping students to slow down, notice details, and connect their findings to the themes of the course. These entries will also serve as a foundation for the culture circle discussions, where students will share and collectively reflect on their observations.

3) Visual essay

For this final assignment, students will write a visual essay of 2000 words + 10 pictures that critically examines how design has shaped their everyday lives and reflects on how it could be different in the future. Drawing on insights from their visual diaries, course materials, and personal experiences, students will explore the visible and invisible dimensions of design in shaping their identities, routines, and interactions.

The visual essay must integrate visual elements—such as sketches from the visual diary, photographs, or other artworks—alongside the written content. These images should not be relegated to an appendix but incorporated seamlessly into the essay, extending and deepening the analysis presented in the text. Images should be appropriately captioned and positioned to enhance the narrative, illustrating key points or providing additional layers of meaning.

Semester outline

01/13/2025 – Design as culture

The first week is an overview of the learning journey ahead. The course starts from the fundamental idea that design plays a significant role in any human culture, particularly in giving form to social identities and personalities. This is not a standard view; most academic courses and publications focus on design as a professional know-how. Here, we will understand design as something everyone can and is already doing. To grasp this uncommon frame of reference, students need to distance themselves from what they have heard, seen, or done about design.

In the first break-out session, teaching assistants will provide a guided tour through the course syllabus and Canvas space, answer questions, and show examples of the materials needed for the assignments, mainly the visual diary. They will also host a class discussion around 10 images created by artist Francisco Brennand for Paulo Freire’s famous literacy program in Brazil. These images are explained in his book Education for Critical Consciousness, which students are advised not to read until the class is over. Since these images have no right or wrong interpretations, it is best not to know what Freire and Brennand wanted to convey by them. Later, students can look at and compare their classmates’ interpretations with the original goal. In addition to this image-text association, students are encouraged tolisten to the Design Observer podcast episode with Dr. Frederick van Amstel before or, at the latest, right after the class. All required readings need to be completed before the in-person session so they may inform the interactive learning experiences.

Required reading/listening/watching for an expected self-study time of 70 minutes:

- Moreau, Lee (Host); Cheng, Alicia; Van Amstel, Frederick; Noel, Lesley-Ann. (2023). Design As S1E1: Culture Part 1. 47 minutes. Design As [Audio podcast]. Design Observer.https://designobserver.com/design-as-s1e1-culture-part-1/

- Freire, P. (2005). Education for critical consciousness. Continuum. Appendix, 55-75.

01/13/2025–01/20/2025: Martin Luther King Jr. day

01/21/2025–01/27/2025: Design culture as world-making

This week explores design’s cultural and existential dimensions, emphasizing its role in shaping the worlds we inhabit. Ben Highmore, Beatriz Colomina, Mark Wigley, and Otl Aicher wrote very different but essential texts to understanding design culture as a world-making activity. Röyksopp’s “Remind Me” music video made by Studio H5 vividly illustrates these ideas, showcasing how design makes certain aspects of everyday life more visible or invisible. Due to the amount of information packed into each frame, replaying and pausing the video is required to get the best viewing experience. Students should take note of the frames they would like to discuss with the class in person by using the following format: Xmin Xsec. Students can also print selected frames and analyze them in their visual diary. In class, teaching assistants will load that frame and facilitate/complicate the discussion supported by the readings.

Required reading/listening/watching for an expected self-study time of 90 minutes:

- Röyksopp. (2002). Remind Me music video. 5 min. Studio H5. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iQpXcLD4wHk

- Highmore, B. (2019). Taste and attunement: Design culture as world making. In: Julier, G., Folkmann, M. N., Skou, N. P., Jensen, H. C., & Munch, A. V. (Eds). Design culture: Objects and approaches, Bloomsbury Publishing. p.28-38.

- Colomina, B., & Wigley, M. (2016). Are we human? Notes on an archaeology of design. Chapter 1: The mirror of design. Zürich, Switzerland: Lars Müller Publishers, 2016. 9-19.

- Aicher, O. (1994). World as Design: Writings of Design. John Wiley & Sons. 179-189.

01/28/2025-02/03/2025 – Reading the designed world

This week introduces Paulo Freire’s concept of “reading the world,” which reframes literacy as more than the ability to decode written words. For Freire, reading is an act of interpreting and critically engaging with the world around us. To explore this idea in action, we watch Peru: Literacy for Social Change (1978), a documentary that illustrates Freire’s critical pedagogy in practice. The film follows educators working with peasants on a Peruvian cooperative cotton farm, using literacy as a tool for organizing to build community houses.

Jane Fulton Suri’s Thoughtless Acts?’s excerpt connects Freire’s ideas to design. By engaging with social scientists like her, designers at IDEO (a major design firm), have learned to read the world before drawing their ideas. Suri’s approach highlights how everyday, intuitive interactions with objects and environments reveal the unspoken needs and behaviors of people. Together, these perspectives challenge students to see design as a process of critical engagement with the world, rooted in understanding and transforming the realities of daily life.

Students should carry their visual diaries to all in-person gatherings from this week onwards. In this session, students may share their childhood world memories like Freire does in his article. Besides drawing from memory in their visual diaries, students can attach copies of their drawings and photographs. Questions to be explored: How did you learn to read your world? What was your world like? What are the significant differences to the world you now live in?

Required reading/listening/watching for an expected self-study time of 70 minutes:

- Strobel, Hans R. and Osterreid, Susanne. (1978). Peru: Literacy for Social Change [Documentary]. 31 minutes. Osterreid Productions. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mSgBkbJbzRs

- Freire, P. (1983). The importance of the act of reading. Journal of education, 165(1), 5-11.

- Suri, J. F. (2005). Thoughtless acts?: Observations on intuitive design. Final chapter: Framing thoughtless acts. Chronicle Books. 162-180.

02/04/2025-02/10/2025: Culture circles and the social design of everyday life

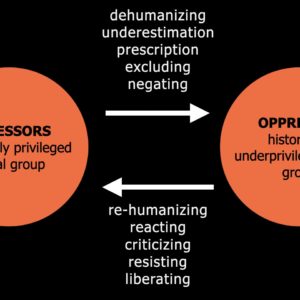

When one reads the real world and understands its underlying contradictions, a seed of hope for changing the world is planted. From this seed, the field of social design emerged in the 1960s. This week introduces the work of Victor Papanek, a pioneer in the field, and the work of Dr. Frederick Van Amstel, one of his many contemporary followers. Professor Alison Clarke presents Papanek’s vision for social design in the video Victor Papanek: The Politics of Design. It is worth reading Papanek’s in his own words. Hence, we have the preface to his Design for the Real World here. Papanek critiques traditional design practices, arguing that design should serve human needs rather than perpetuate wasteful consumption. His philosophy calls for socially and ecologically responsible design that prioritizes the well-being of marginalized communities.

Building on this foundation, we explore how Dr. Frederick van Amstel implements these principles in his pedagogy and research. In the podcast Design Pedagogy, the Body, and Solidarity in Designing Commons, Dr. van Amstel discusses how participatory methods like Theater of the Oppressed foster solidarity and shared ownership in design education. In Social Design at the Brink: Hopes and Fears, coauthored by Dr. van Amstel, there is a description of an application of the Culture Circles method devised by Paulo Freire to discuss contemporary social design issues. This method underscores much of the pedagogical approach for this class. In the in-person session, the teaching assistants will present and discuss a few social design projects they are working on as part of their graduate research.

Required reading/listening/watching for an expected self-study time of 90 minutes:

- Design Museum Den Bosch. (2022). Victor Papanek: The Politics of Design with Alison Clarke . 5 minutes. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7E_4d9vxuBA

- Papanek, V. (2005). Design for the Real World: Human Ecology and Social Change. Ix-xiv.

- Poderi Giacomo (host); Marttila, Sanna-Maria (host); Saad-Sulonen, Joanna (host); van Amstel, Frederick. Design pedagogy, the body, and solidarity in designing commons. Commoning Design & Designing Commons . 46 minutes. https://fredvanamstel.com/blog/design-pedagogy-the-body-and-solidarity-in-designing-commons

- Fonseca Braga, M., M. C. van Amstel, F., and Perez, D. (2024) Social Design at the Brink: Hopes and Fears., in Gray, C., Hekkert, P ., Forlano, L., Ciuccarelli, P. (eds.), DRS2024: Boston, 23–28 June, Boston, USA. https://doi.org/10.21606/drs.2024.1538

02/11/2025-02/17/2025: Observing and sketching design in everyday life

This week consolidates the most important skill to be developed and evaluated in this course: observing, reflecting, and sketching design in everyday life. First, Georges Perec’s essay Approaches to What? Introduces the concept of “extraordinary”—the seemingly mundane aspects of daily existence that we often take for granted, like design. Perec challenges us to find meaning in the ordinary, framing it as a rich site for inquiry and interpretation. His perspective encourages us to slow down and pay attention to the unnoticed details that shape social life.

Inspired by Perec, Lynne Chapman, a fine artist, assisted a group of sociologists in her residency at the Morgan Centre for Research into Everyday Lives, University of Manchester, to use drawing as a means to grasp everyday life. Most of them thought they did not know how to draw. However, as Lynne explained in the video Unfolding Stories, any simple doodle could do it. Her chapter for the Mundane Methods book, coauthored with one of these sociologists, describes the collaboration in detail. The final section includes an exercise suggestion that students of this class should execute in their visual diaries to read the designed world. Andrew Causey’s book chapter, Dare to See and Dare to Draw, encourages even the most insecure to observe culture through sketching. In the in-person session, graduate teaching assistants will suggest other exercises. Students who experience creativity blocks while trying to sketch can reach out to the assistants during office hours for personalized instruction.

Required reading/listening/watching for an expected self-study time of 100 minutes:

- Perec, G. (2002). Approaches to what?[1973]. In: Highmore, Ben (Ed.).The everyday life reader, 176-178.

- University of Manchester Sociology department (2016). Unfolding Stories: Sketching the everyday . 15 minutes. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aAK1PhY-pyo

- Heath, S., & Chapman, L. (2020). The art of the ordinary: Observational sketching as method. In Mundane Methods (pp. 103-120). Manchester University Press.

- Causey, A. (2017). Drawn to see: Drawing as an ethnographic method. Chapter 3: Dare to see and dare to draw. University of Toronto Press. 49-70.

02/18/2025-02/24/2025: Sensing the rhythms of everyday life

Observing everyday life without a specific focus is hard. In this week, we are going to focus on rhythms. Before discussing the role of design in shaping rhythms in the following weeks, we pay attention to the role of technology in its broadest sense (not just digital). We begin with Dr. Frederick van Amstel’s lecture, Dancing Algorhythms in the Theater of the Techno-Oppressed, which examines how algorithms disrupt the human body (circadian) rhythms. Next, we watch Grasping the Rhythms of the City by Dr. Dawn Lyon, which takes us to the Arc de Triomphe in Paris to observe urban rhythms in practice. Produced as part of the University of Kent’s Urban Ethnography Summer School, this short film demonstrates rhythmanalysis—a method for studying city life’s flows, patterns, and interruptions. Henri Lefebvre and Catherine Regulier’s seminal text The Rhythmanalytical Project provides the theoretical foundation for rhythmanalysis, examining the interplay of natural, social, and technological rhythms.

Finally, we watch Koyaanisqatsi, a cinematic masterpiece juxtaposing natural and human-made rhythms. Directed by Godfrey Reggio and scored by Philip Glass, the film provides a meditative exploration of the impact of technological progress on the environment and human existence. Students are encouraged to take visual notes while watching this movie and going through the entire week. In the in-person session, teaching assistants will share examples and exercises of sketching everyday life rhythms.

Required reading/listening/watching for an expected self-study time of 120 minutes:

- Van Amstel. Frederick M. C. (2023). Dancing Algorhythms in the Theater of the Techno-Oppressed . 11 minutes. https://fredvanamstel.com/talks/dancing-algorhythms-in-the-theater-of-the-techno-oppressed

- Lyon, Dawn. (2019). Grasping the rhythms of the city: doing rhythmanalysis at the Arc de Triomphe, Paris . 5 minutes. Kent School of Social Policy, Sociology and Social Research. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dBOD089o5WE

- Lefebvre, H., Régulier, C., & Zayani, M. (1999). The rhythmanalytical project. Rethinking Marxism, 11(1), 5-13. https://doi.org/10.1080/08935699908685562

- Reggio, G., & Glass, P. (1983). Koyaanisqatsi [movie]. 86 minutes. MGM Home Entertainment.https://tubitv.com/movies/302693/koyaanisqatsi (also available at Amazon Prime and MGM+ with no ads).

02/25/2025-03/03/2025: Visible designs: identity and difference

This week, we examine the contradiction between identity and difference as it manifests through design. Objects function as markers of identity, signifying shared belonging, yet they simultaneously differentiate individuals and groups, reinforcing social divisions. This dialectical tension shapes how objects are designed, used, and interpreted, making visible the broader social dynamics of inclusion and exclusion. By engaging with this contradiction, we uncover how design mediates the forces that unite and divide society.

Gary Hustwit’s Objectified highlights how designers balance universal functionality and individual expression. The movie showcases objects that aim to connect users while reflecting personal identity. Adrian Forty’s chapter Differentiation in Design delves deeper into how design historically facilitated social distinction, particularly in consumer goods. Forty examines how objects have been imbued with meanings of status, class, and exclusivity, often through deliberate design strategies. Together, these materials challenge students to reflect in their visual diaries how their belongings and lack thereof include or exclude them in certain groups, communities, and spaces. The in-person session will consist of a discussion about the role of design in sustaining and distributing material privileges.

Required reading/listening/watching for an expected self-study time of 120 minutes:

- Hustwit, Gary. (2009). Objectified: Manufactured Objects and their Designers [movie]. 65 minutes. https://www.kanopy.com/en/ufl/video/2931959 (requires UF’s VPN connection)

- Forty, A. (1986). Objects of desire: designs and society 1750-1980. Chapter 4: Differentiation in Design. London: Thames and Hudson. 62-93.

03/03/2025-03/10/2025: Invisible designs: alienated work and everyday life

This week, we explore the invisible dimensions of design—those that structure our environments and interactions in often unnoticed ways. Invisible design shapes everyday life, from the systems behind urban infrastructure to the processes that regulate social behavior. However, this very invisibility can alienate individuals from the labor, intentions, and decisions that underpin their environments, leaving critical aspects of design’s influence obscured. Gary Hustwit’s Urbanized demonstrates how urban design embodies this invisibility. The film unveils the hidden strategies and compromises behind city planning, showing how transportation systems, public spaces, and urban layouts are designed to structure daily life without being consciously acknowledged. Lucius Burckhardt’s Design is Invisible essayextends this idea, emphasizing that the most impactful designs operate behind the scenes, embedded in the planning and systems that shape societal functions.

Finally, John Heskett’s introduction to Toothpicks and Logos reflects this week and the prior week, asking the foundational question: What is design? Is it visible, invisible, or both? Heskett avoids a single definition of design, instead presenting design as a complex and multifarious practice that mediates between purpose and form, intention and materiality. Students should take visual notes and pictures, attach product wrappings to their visual diaries, and collect any invisible designs they come across throughout the week. These will be shared with classmates in the in-person session, during which a map of the invisible design will be compiled.

Required reading/listening/watching for an expected self-study time of 120 minutes:

- Hustwit, Gary. (2009). Urbanized: The Issues and Strategies Behind Urban Design [movie]. 85 minutes.https://www.kanopy.com/en/ufl/video/2874827 (requires UF’s VPN connection)

- Burckhardt, L. (2017). Design is invisible: planning, education, and society. Birkhäuser. p. 15-26

- Heskett, J. (2002). Toothpicks and Logos: Design in Everyday Life. Chapter 1: What is design? Oxford University Press. p.2-11.

03/11/2025-03/17/2025 – Spring break

03/17/2025-03/24/2025: Visible designs with invisible consequences: Typography

This week, we explore the dialectical tension in typography (a.k.a. as fonts) as a design practice that is both visible in its forms and invisible in its broader cultural and political consequences. On one hand, typography conveys text. On the other hand, it conveys context: cultural identity, authority, and belonging. Gary Hustwit’s Helvetica examines the rise of a famous font as a global design standard, celebrated for its supposed clarity and neutrality. Kurt Campbell’s article The Sociogenic Imperative of Typography reflects on the failed attempt by South Africa to craft a new national identity through imported supposedly neutral typefaces after apartheid. Campbell shows how typography, rather than unifying, revealed the contradictions of a society grappling with its diverse and fractured identity.

Students are encouraged to explore these contradictions through their visual diaries by observing the expression of American multiculturalism in typography. Pay attention to how typefaces reflect cultural diversity or reinforce dominant narratives in your home (e.g., on packaging, books, or digital interfaces) and in public spaces (e.g., shop signs, billboards, or public transportation systems). Teaching assistants will provide technical details on analyzing a font in the in-person session.

Required reading/listening/watching for an expected self-study time of 120 minutes:

- Hustwit, Gary. (2007). Helvetica: Typography, Graphic Design and Global Visual Culture [movie]. 80 minutes.https://www.kanopy.com/en/ufl/video/2874825 (requires UF’s VPN connection)

- Kurt Campbell (2013) The Sociogenic Imperative of Typography, European Journal of English Studies, 17:1, 72-91, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13825577.2013.755002

03/25/2025-03/31/2025: Visible designs with invisible consequences: Toys

This week, we examine the contradiction inherent in toys as visible designs that simultaneously reveal and obscure their use to shape children’s and adults’ identities. Toys are not just objects of play; they are used as models for idealized selves and/or prejudiced others. Jason Godfrey’s Japan’s Obsession With Being Kawaii documentary introduces the power of cuteness in toy design, revealing how Kawaii aesthetics shape cultural expressions and norms. However, as L. Bow’s Racist Cute: Caricature, Kawaii-Style, and the Asian Thing article demonstrates, the seemingly benign aesthetics of cuteness can mask racial caricatures and reinforce stereotypes.

Finally, curator Dominique Jean-Louis walks us along the exhibition Black Dolls at The New York Historical Museum. She explains that while some Black dolls have historically perpetuated stereotypes, others have liberated Black children by providing affirming representations of their identity. The topsy-turvy doll is fascinating to grasp the contradiction behind the White-Black racial difference. Students are encouraged to remember, look at pictures, and draw from memory in their visual diaries how their childhood toys shaped who they were back then and now.

Required reading/listening/watching for an expected self-study time of 90 minutes:

- Godfrey, Jason. (2022). Japan’s Obsession With Being Kawaii . 24 minutes. Beyond Documentary. Beyond Distribution. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1IODXpVVyU4

- Bow, L. (2019). Racist cute: Caricature, kawaii-style, and the Asian thing. American Quarterly, 71(1), 29-58.https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.2019.0002

The New York Historical. (2022). If These Dolls Could Talk: The Hidden History of Black Dolls . 6 minutes.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=prNuSUjWa00

03/31/2025-04/07/2025: Visible designs with invisible consequences: Yards

This week, we challenge the notion that yards are natural spaces, revealing them instead as designed environments shaped by cultural ideals and ecological trade-offs. While often perceived as organic extensions of the home, yards are highly curated landscapes that reflect societal values about order, beauty, and property. However, these designs have hidden consequences, such as water overuse, biodiversity loss, and chemical pollution. Roman Mars’ podcast episode Lawn Order from 99% Invisible offers a fascinating exploration of this topic, including the story of a Florida man sent to jail for not caring for his lawn. As a podcast dedicated to the hidden stories of everyday design, 99% Invisible is highly recommended for listening along following this course.

Joan I. Nassauer’s Messy Ecosystems, Orderly Frames is a design research that reconciles cultural aesthetics with ecological needs: creating landscapes that integrate natural, “messy” elements within visually “orderly” frames. This approach is exemplified in Flip My Florida Yard: The De Las Alas Family, a real-world transformation developed in partnership with the University of Florida’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS). Students are encouraged to walk around their neighborhoods, notice the gardens, yards, and lawns, and wonder: How do these designed environments create an identity for this place? When appropriate, sketch down some views and talk to neighbors about that. Which changes are considered possible or impossible concerning environmental sustainability? Students may share the contradictions they found using Lego Serious Play during the in-person session, a technique explained in Dr. Frederick van Amstel’s recorded lecture.

Required reading/listening/watching for an expected self-study time of 120 minutes:

- Mars, Roman. (2015). Lawn Order [podcast episode]. 19 minutes. 99% Invisible. Episode 177.

- https://99percentinvisible.org/episode/lawn-order/

- Nassauer, J. I. (1995). Messy ecosystems, orderly frames. Landscape journal, 14(2), 161-170. https://doi.org/10.3368/lj.14.2.161

- Crawford, Chad. (2023). Flip My Florida Yard – The De Las Alas Family . 21 minutes. S1E1. Florida Department of Environmental Protection and University of Florida IFAS. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9s2f7YJJTms

- Van Amstel, Frederick M. C. (2023). Reading the world with Lego Serious Play . 30 minutes.https://fredvanamstel.com/talks/reading-the-world-with-lego-serious-play

05/07/2025-04/14/2025 – Design across worlds

At the end of this course, we consider design in other worlds, across worlds, and within many worlds. These two weeks are going to be the hardest of all to follow as they raise consciousness of worlds unlike the world(s) where this course is taking place. Since each instructor came to the United States of America from a different world, this is a great opportunity to reflect on such differences. First, we watch Hubert Sauper’s reflective documentary Epicentro, a poignant exploration of a Caribbean island grappling with the legacy of colonialism and imperialism. The depiction of everyday life in a place where people are constantly challenged to make do is illuminating. The chapter Coloniality of Making Design Philosophy by Van Amstel, Saito, and Gonzatto offers a deep reflection on the consequences and possibilities for design in such contexts. None of these references suggests clearly what to do with the remnants of colonialism, a suggestion reserved for the next and final week.

To prepare for this culture circle, students should take pictures, notes, and collect product labels around them. The question we are going to discuss is: where is your world made? US? China? Where else? Where is it designed? What are the implications of this design across worlds?

Required reading/listening/watching for an expected self-study time of 140 minutes:

- Sauper, Hubert. (2020). Epicentro [movie]. 110 minutes. https://www.kanopy.com/en/ufl/video/11178020(requires UF’s VPN connection)

- Van Amstel, F. M. C. Saito, C. Gonzatto, R. F. (forthcoming). Coloniality of making design philosophy. In: Verbeek, P., Secomandi, F. (Eds.) Design Philosophy after the Technology Turn. Bloomsbury Academic. 1-15.

04/14/2025-04/21/2025 – Designing a world of many worlds

In this final week, we confront the challenge of designing not just across multiple cultures but multiple worlds—distinct ways of knowing, being, and designing that may coexist in the pluriverse, a metaphor that suggests what the United States of America designed world(s) could be something else than a multicultural nation. We begin with the podcast Design as Pluriversal Design, hosted by Lee Moreau, and featuring Dr. Frederick van Amstel and Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel. Subsequently, we read Victor Udoewa and his colleagues speculative dialogue on the conditions for the pluriverse. Dr. Noel’s article Redesigning the Field complements these perspectives by proposing actionable steps to reimagine design education and practice as tools for embracing plurality. Together, these materials invite students to join the closing in-class debate on the transformations required to observe and design for a world of many worlds.

Required reading/listening/watching for an expected self-study time of 90 minutes:

- Moreau, Lee (host). Leitão, Renata. Van Amstel, Frederick. Noel, Lesley-Ann. (2025). Design as Pluriversal Design. Design Observer. 43 minutes. https://designobserver.com/design-as-pluriverse/

- Udoewa, V., Gutiérrez Borrero, A., Noel, L., Ruiz, A., Borchway, N.K., Lodaya, A.,and VAN AMSTEL, F.M.(2023) When Is the Pluriverse?, in Derek Jones, Naz Borekci, Violeta Clemente, James Corazzo, Nicole Lotz, Liv Merete Nielsen, Lesley-Ann Noel (eds.), The 7th International Conference for Design Education Researchers, 29 November – 1 December 2023, London, United Kingdom.https://doi.org/10.21606/drslxd.2024.109

- Noel, L. A. (2023). Redesigning the field. Arcos Design, 16(1 (Suplemento)), 72-86. https://www.e-publicacoes.uerj.br/arcosdesign/article/view/79288

04/21/2025-04/28/2025 – Exams

A week reserved for receiving feedback on the writing assignment.