Abstract: Imagine a design studio where aspiring designers break free from traditional hierarchies and redefine what it means to be a designer. In the self-managed studio developed at UTFPR, design students learned that design can serve not just industries but social movements and the public. Inspired by critical pedagogy and radical practices like Theater of the Oppressed, students turned existential crises into creative fuel, crafting tools like a crisis card deck to navigate their role in a complex world. They didn’t just learn skills—they learned to design for themselves as a collective, harnessing self-knowledge to confront oppression and reimagine design’s purpose.

This lecture was recorded in the Spring 2025 Research and Practice MXD MFA course at the University of Florida.

Video

Audio

Full transcript

This presentation will provide an overview of my past experience trying to push forward this idea of self-management in design studios. I’m attempting to transplant these practices from Brazil to the United States, specifically here at the University of Florida. And you’re part of this experiment. I’m proposing this, and we’re going to try, but I don’t know if we’re going to succeed or to what extent we’ll be able to. We’ll probably need to adapt things. But here’s my attempt to share, in a few minutes, what it was like doing a self-managed studio in Brazil.

First of all, I want to talk a little bit about self-management in general, which is not a term that has been associated much with design. I became involved with self-management through social movements, particularly the workers’ movement, which is guided by ideologies and proposals like socialism and anarchism. Self-management is also practiced by other social movements. For example, the way women organize under the principle of sorority is somehow relatable to self-management.

So basically, in many of these social movements, self-management means managing the self. And that’s the opposite of managing the other, or hetero-management. And as you’re probably suspecting when I say hetero-management—am I really talking about heteronormativity here? Sort of. Hetero, the word, means “other”. If you are a heterosexual it is because you are attracted to the other gender—that’s the definition. But hetero does not only mean “other” in terms of sexuality. It also means “any other”. Here, we’re talking about managing the other rather than managing the self, which is an interesting aspect of this word hetero-management.

The concept of hetero-management was created by the workers’ movement to criticize the capitalist work structure or system. It has since been enriched by other social movements: the Black movement, the feminist movement, and the disability rights movement. They’ve added new characteristics to the understanding of hetero-management, describing it as straight, White, patriarchal, capitalist, ableist, and so on. The most oppressive sides of human relationships are all systematized in hetero-management.

Hetero-management is typically depicted as a pyramid where those at the top manage those at the bottom. But that means no one is managing those at the top. Think about it—people at the bottom don’t manage themselves, and no one manages those at the top. Essentially, no one manages themselves. That’s the biggest hurdle of hetero-management. If you focus too much on managing others, you may act against your best interests. Conversely, your actions may backfire on you in the long run.

For example, the simplest way to explain it is this: how far can capitalism go on a planet with limited boundaries for extracting natural resources? The planet, at some point—and it’s already happening—shows the effects of depletion, excessive pollution, overconsumption of resources, and excessive emissions that produce greenhouse effects, among other things. One possible explanation for this is the over-reliance on hetero-management. People at the top don’t think about themselves; they don’t, for example, consume less. By not consuming less, how can they set an example for those at the bottom? Without such examples, everyone wants to consume more than the planet can provide. And that’s what happens in general in the United States, which is a country deeply rooted in the capitalist structure.

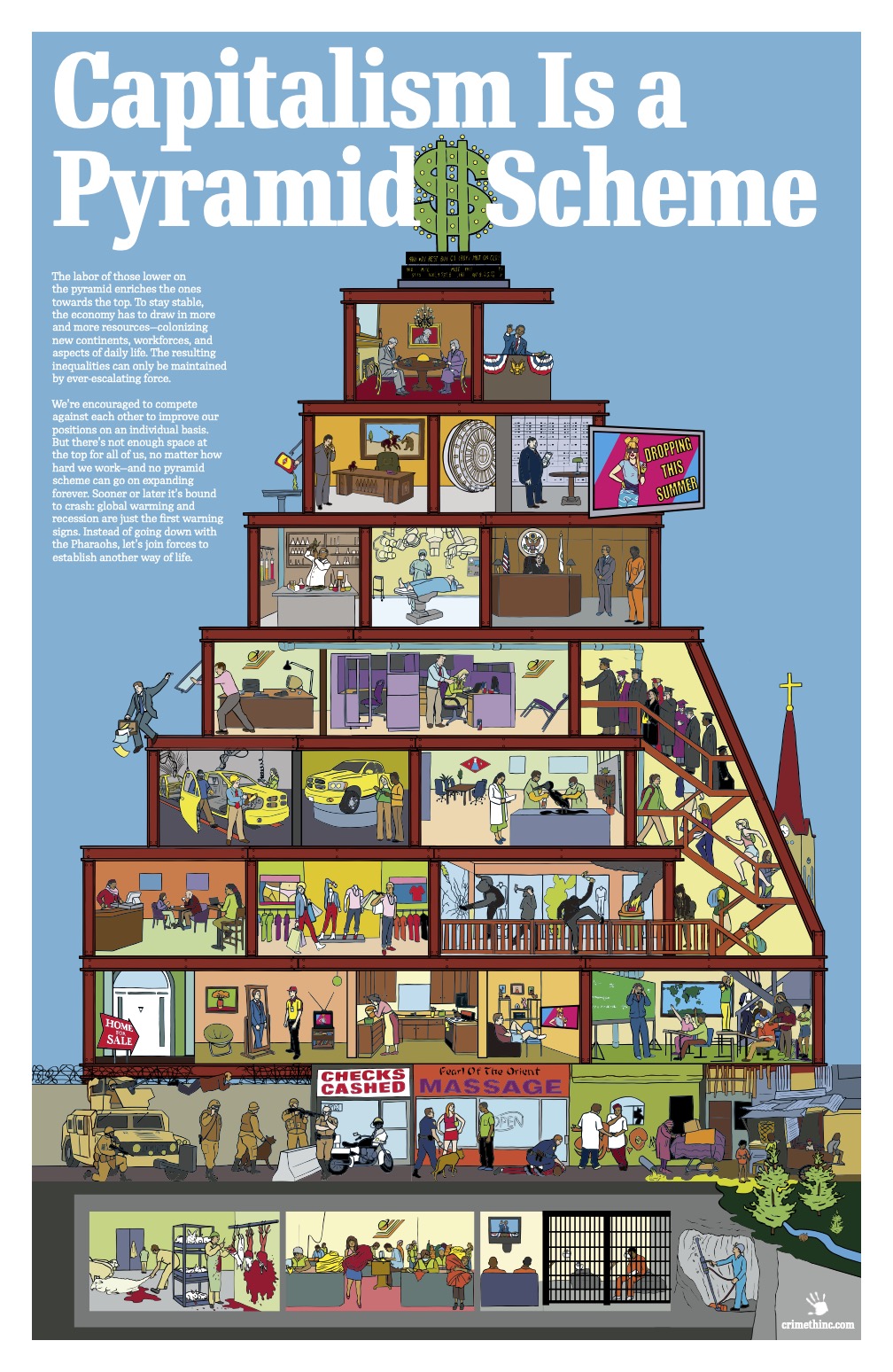

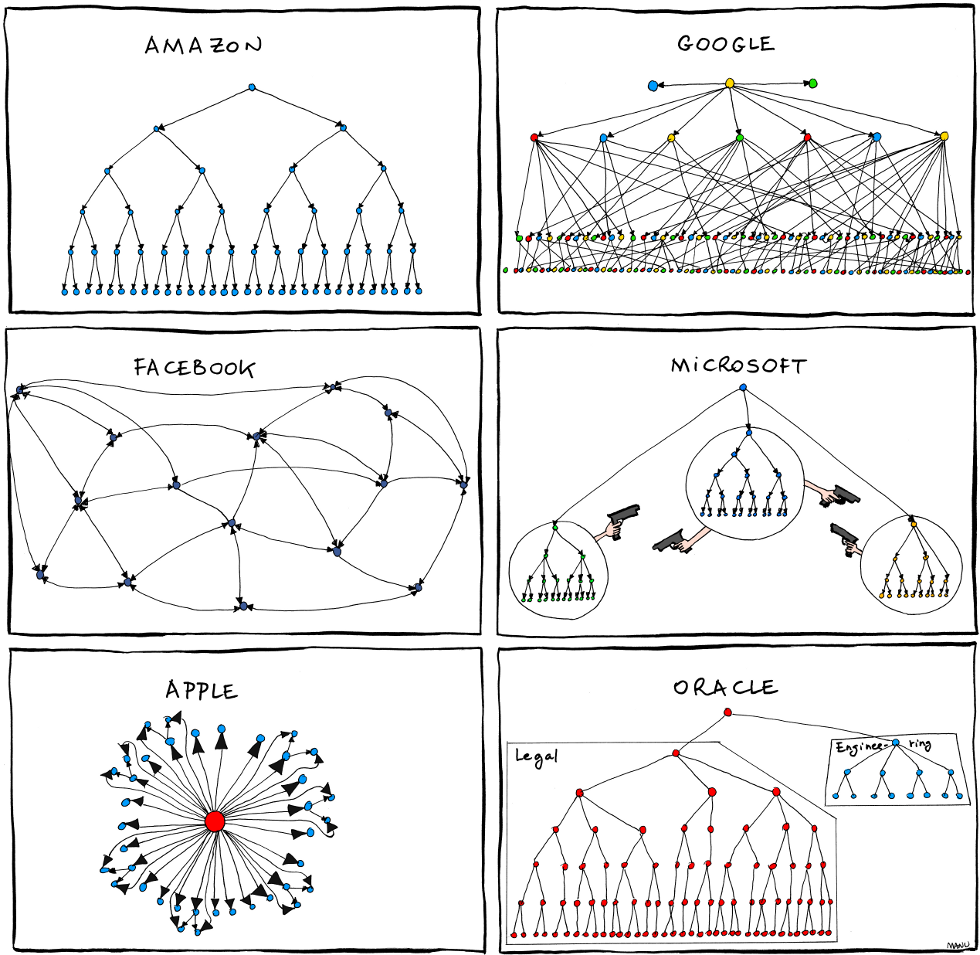

This artwork you are seeing here is a rich depiction of the capitalist structure. Many of these examples come from the United States. I just want to mention that it was created by CrimethInc, an anarchist collective. It’s an interesting ironic name. An incorporated enterprise that produces crimes against capitalism, or, in other words, they produce fascinating, critical, punk, anarchist, and anti-capitalist work.

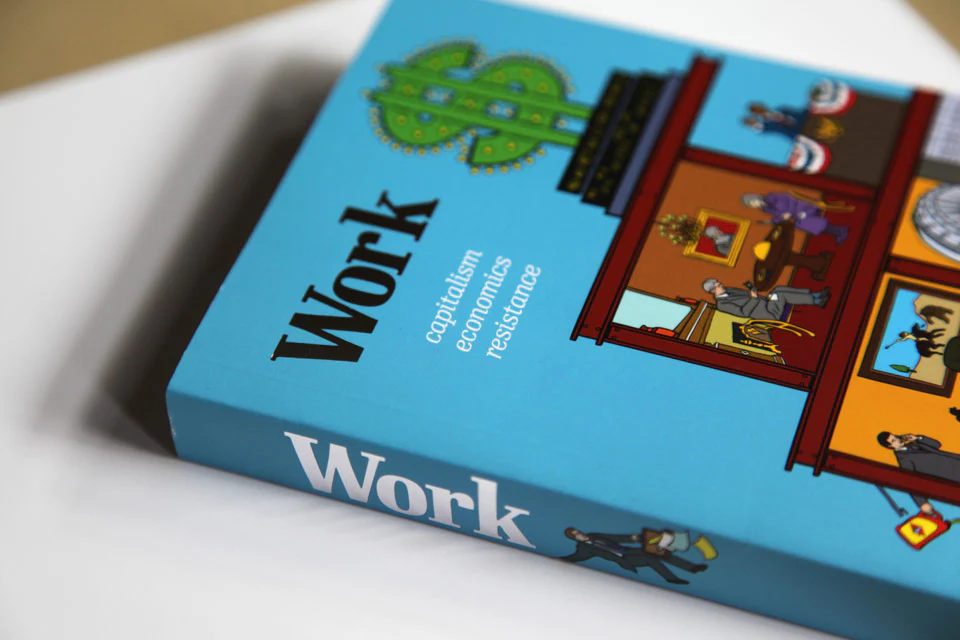

They have a beautifully illustrated book about work—a critique of alienated labor under capitalism—with very interesting design artworks that aim to provide a systemic view of the system. Later, you can explore it to understand why people are at the bottom, how they are being exploited, and through which mechanisms. Once you start to examine the ways they are being exploited, you will clearly see the role of design in it.

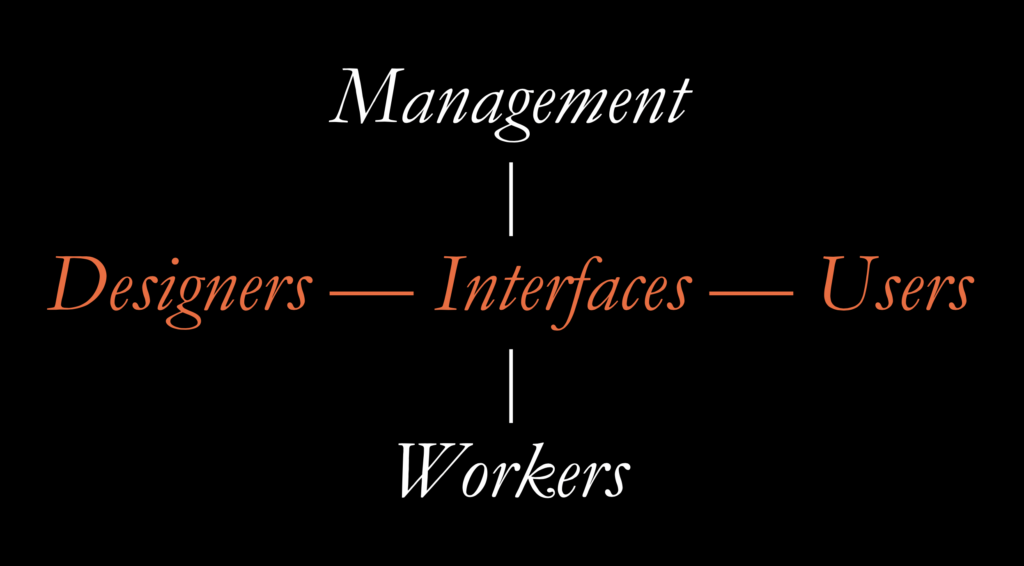

Design is essentially mediating all the social relationships you see in this picture. There are many interfaces here. Gui Bonsiepe (1999) once wrote that everything design produces is an interface, whether it’s graphics on printed paper or a product physically positioned in a room. These are all interfaces, and designers are the ones responsible for creating them. However, these interfaces often function to maintain the current structure, keeping it standing, although in a very precarious way.

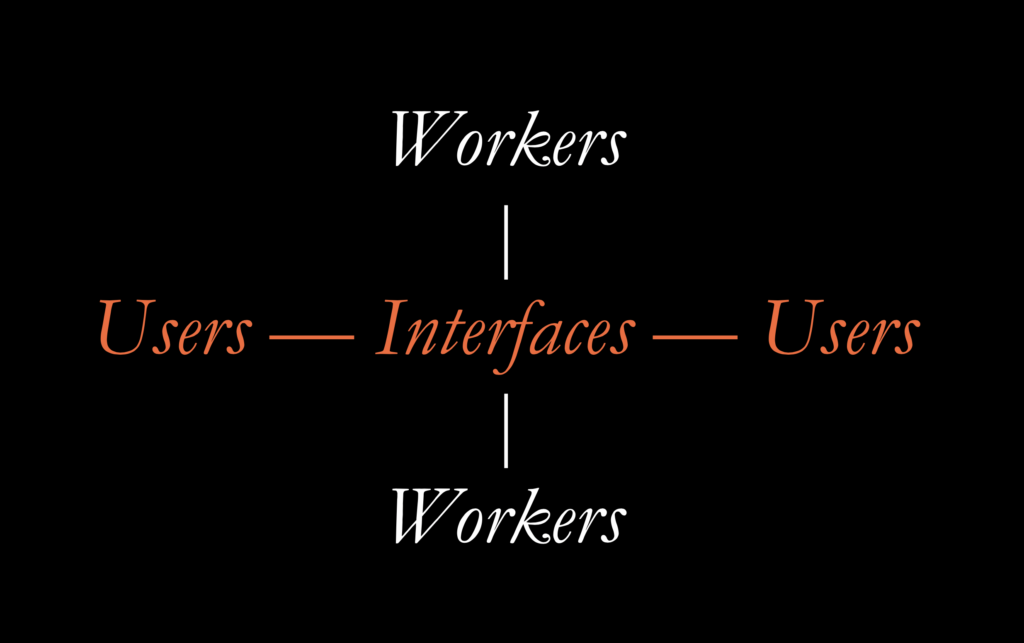

Here’s a diagram to help you think about how design works in hetero-management. You have, of course, the hierarchy between managers and workers: managers at the top, workers at the bottom, and interfaces between them that play many roles. But most importantly, these interfaces act as buffers that alleviate the tension between these two collectives.

If managers are exploiting workers, workers sometimes get fed up. They might want to retaliate—history provides examples of this—or seek revenge in other ways. That’s why managers often keep themselves physically distant from workers. They will typically install their offices above factories, where they can watch over workers on the shop floor. This creates an interface that both produces and maintains inequality while alleviating tension.

Why are designers on the horizontal line? Why aren’t designers and users on this vertical line? Because designers and users hold somewhat ambiguous roles in society. If you say you’re a designer, you may be a real manager, however, in capitalism, most of the times, designers are workers who thinks to be managers. That is what Marx called false consciousness, not knowing in which class you are. Designers act as if they were trying to exploit workers. But in doing so, they end up enabling their real managers to exploit themselves even more.

This is also what happens when designers start to think they are entrepreneurs. They see themselves as creative professionals who can work out of bounds, developing their creativity and expressing their freedom to create. But, at the end of the day, they still need to pay their bills. And those bills will be paid by the money they receive from clients, who will impose restrictions and constraints on their projects. In this way, designers remain bound to the same structure.

Whereas for users, similarly, they may think they don’t have a connection or, for example, a work contract with an employer—the managers. But they are still being managed in a soft way. For example, as users of Microsoft or any other big tech company, we might think that their technologies have been designed for us in a neutral way. We might think we can do whatever we want with them, but the reality is that those big tech companies are managing crowds through these technologies—crowds of users who are now supposed to replace crowds of citizens. Nowadays, we see big tech coming so close to the government of the United States that they are even taking some high-level seats. This means that big tech and the government are working together. For what? To reduce citizens to the position of users so they don’t even think of reclaiming democratic participation and workers right.

Design is playing a major role in such historical reduction of democracy and workers rights by designing the interfaces that hide what is going on at the backstage. Nevertheless, as much as designers can serve the managers, they can also serve the workers. That’s basically what self-management made me figure out. Before we jump into what design can do in this context, let’s take another look at the history of self-management. I’m just going to show you two images about it. You can search later to get more information, and I know some designers with many different experiences—learning about, listening to, or even using socialist structures. You can reach out to them later if you will.

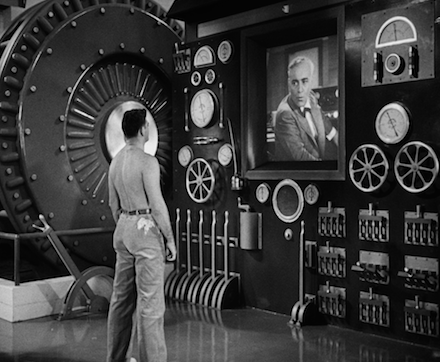

This movie is accessible to everyone: Modern Times by Charlie Chaplin. In 1936, he created one of the most significant pieces ever made for cinema, which already provides a fascinating critique of the capitalist work structure, hetero-management, and their interfaces. This picture from the movie looks like something you could see today, right? There’s a boss talking to a worker. The worker is half-naked, and the boss is fully dressed in a suit, talking through a television. In 1936, these technologies were fictional at the time but it was rather obvious that managers would use them once they become available. Chaplin anticipated something that would become widespread—especially after the COVID pandemic of 2020: Managers popping up on your screen, demanding work from you, or even surveilling your work—looking at you without letting you look back at them. This is all an interface.

Now let’s consider another possibility. Just as there are interfaces for hetero-management, there are also interfaces for self-management. I’m bringing here an example from Yugoslavia just because it was probably the socialist country with the most advanced self-managing practices in human history. This picture, taken in 1976, depicts an assembly of workers in a textile factory. As you can see, there are many women participating, and everyone has a say in the future directions of the factory—what they’re going to produce, how much they’ll produce within a given time, and the overall plans for the factory’s future.

These decisions were all discussed among the workers, and they could change the direction of the factory. That’s not something you typically see in a capitalist company. Many critics of hetero-management, like Ricardo Semler, are trying to update it and infuse it with socialist practices. Thanks to these critics, self-management is even being incorporated by tech companies, especially those with idealistic premises like wanting to change the world for the better. At some point in their history, many of these companies experiment with self-management to some degree. Of course, as they grew, they typically abandoned it.

In Yugoslavia, however, self-management persisted even in large organizations because it was supported by a socialist ideology. When capitalism is the dominant ideology, it’s challenging to maintain self-management. That’s why counter-ideologies are necessary to balance it out. Only in a democracy can these ideologies confront each other in a productive manner.

What I want to emphasize is that this, too, is an interface. Designers have a role in shaping how people can participate, have dialogues, make decisions, and work together in a democracy. Doesn’t this sound a lot like participatory design? Yes, you’re anticipating my point. Designers can indeed facilitate or complicate self-management.

The main question here is how can they learn to do this?

I learned self-management by engaging with social movements. I designed a platform with them, still online today, called Corais. Through it, we designed many things, including a digital social banking system where each community could design its own currency, so to speak. This platform has been applied in hundreds of projects in Brazil. We’re going to discuss this in more detail next week, so I won’t go further into it now. Today, I want to focus on LADO and my experience of trying to bring self-management to the Federal University of Technology – Paraná (UTFPR) before LADO was born, which ultimately led to its co-founding in 2021.

Back in 2019, when I had just started there, I had this idea: to learn designing self-management interfaces, design students first needed to experience self-management directly. They needed to manage their own studio. That’s not a trivial task, though. A studio is not like a factory as it draws from a much older organizational style—the master-apprentice relationship. In this model, every studio has a master—the person who best understands the techniques, tools, modes of expression, and aesthetics. Learners play the role of assistants, helping the master achieve their goals. While assisting, they learn to do what the master does and, eventually, may replace the master. But this only happens after many years of staying in a humble position. It’s not entirely self-management because most of the time, it’s hetero-management.

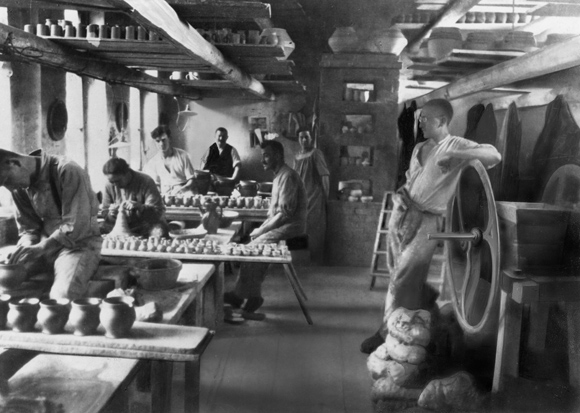

The Bauhaus introduced some changes to the design studio, reframing it as workshops. At the Bauhaus, there were no studios—there were workshops centered on technologies. For example, there was a wood workshop and a steel workshop. However, there were still masters of these workshops, and although they were occasionally replaced, the figure of a commanding individual remained. The Bauhaus also incorporated more hetero-management practices from industry, mimicking some of the divisions of labor found in factories.

This picture from the Bauhaus ceramics workshop in 1924 shows elements of mass production and assembly lines. It’s not fully developed, but you can see that it’s not the usual ceramics studio. Traditional ceramics studios are often messy, but this one is highly organized, with rationalized space usage typical of factories.

Here, we see a pushback against the partial studio self-management of before. The Bauhaus, as you know, was a reference for Hochschule für Gestaltung in Germany, which set the tone for most design education that followed. The basic curriculum of Ulm was replicated in many schools abroad, including in the United States and Brazil. In Brazil, it influenced Escola Superior de Desenho Industrial (ESDI) in Rio de Janeiro, the city where I was born.

At ESDI, the professors were the masters, playing the role of those who “donated” knowledge to students. Students simply followed their rules. This hierarchical relationship in education ties back to colonization. In ESDI, the hierarchy was stronger than in Germany because Brazil wasn’t colonized by Germany but by Portugal. As a result, Brazil—and ESDI—still struggles with a strong appreciation for what comes from colonizing metropolitan centers like Portugal or Germany.

Coming back to my question: how do we overcome hetero-management in the design studio? From 2019 to 2022, I ran an elective course called Designing for People: Laboratory of Design and Social Innovation at UTFPR. I used this elective as a laboratory to experiment with self-management. In the first class, which I co-taught with my colleague André Lucca, we asked students: What do you want to study? We didn’t have a plan or syllabus. We wanted to construct it together.

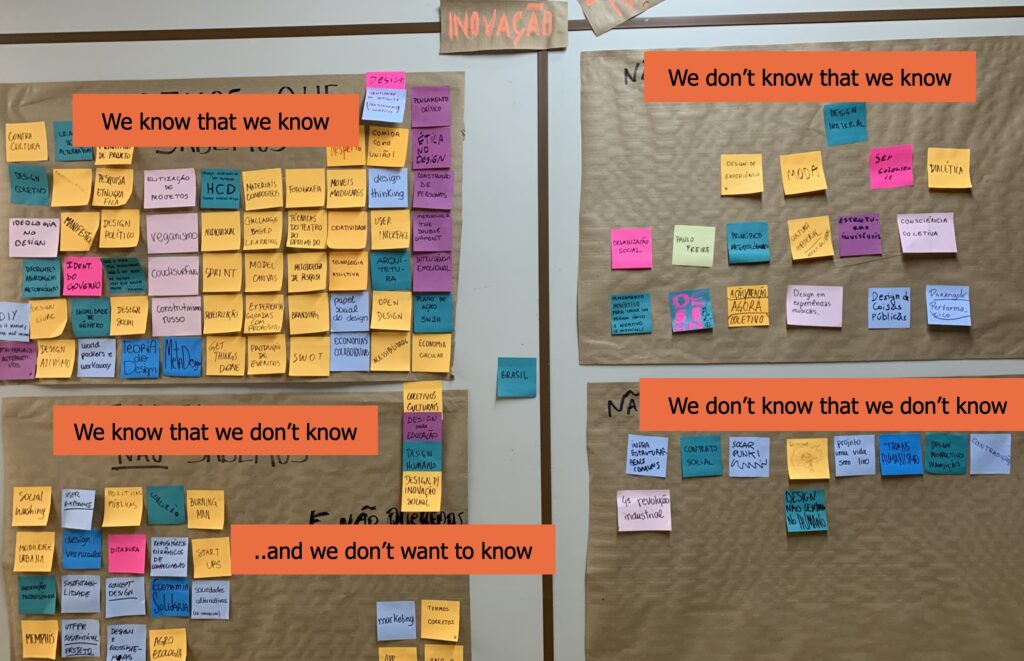

We gave students sticky notes and asked them to write themes they wanted to study. We ended up with many post-its but weren’t sure how to organize them into a study plan. The students began discussing what they knew and what they didn’t know. They started making two different piles: “Oh, I already know this,” and “Oh, but I don’t know.” They started discussing these things, asking, “Onto which pile should I put this?”

Then, I remembered a game called The Blind Side, created by David Gray and his colleagues. It’s part of a book called Gamestorming. In this game, players sort sticky notes into four categories: the knowns, the don’t-know-knowns, the known-don’t-knows, and the unknown-unknowns. We adapted the labels to make them clearer. On our board, we added the pronoun “we”: “We know that we know,” or “We know that we don’t know.” This made the subject of the knowledge clearer. We weren’t talking about the knowledge of one individual; we were referring to the shared knowledge of the studio. Then a new question arose: if someone knows something, do the others also know it? Well, they could know—someone just needed to share it.

Coming back to self-management, in that approach, workers need to know the history of their tools. Otherwise, they may be hetero-managed through those tools. I know that Azadeh and Lucia have done a lot of work on studying the background of The Blind Side game, but not all of you are aware of it. That’s why I’ll share a bit of this information here.

The game was designed based on what we now call the Rumsfeld/Žižek matrix. Donald Rumsfeld, a former U.S. Secretary of Defense, became widely known in the history of knowledge management for his infamous explanation of why the U.S. invaded Iraq in 2003. He explained it with the idea of “unknown unknowns”—a concept he used to justify the invasion. A lot of journalists believed he was bamboozling the media, and indeed he was. Here are his actual words:

Reports that say something hasn’t happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns—there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns—that is to say, we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don’t know we don’t know.

Now, back to my words. You can justify almost anything using that explanation, right? Why did you do something? You can just reproduce that same discourse for any reason. It doesn’t say much of substance, yet it sounds wise. Rumsfeld embraced the idea further, putting it in the title of his biographic book Known and Unknown: A Memoir. He basically acknowledge the bamboozling reputation he got. Yet, his reputation is far worse than that. This man has been accused of responsibility for the deaths of millions of people. Some even consider him a war criminal because the Iraq war was largely unfounded. All those claims about chemical and biological weapons—suggesting they might exist or even worse weapons that “they didn’t even know existed”—turned out to be baseless.

Iraq had a dictator trying to hold the country together. After the U.S. invasion, the country never regained its previous level of economic activity or sovereignty. Even today, Iraq and much of the Middle East remain in a fragile political state, partly because of that war. Rumsfeld used this seemingly wise but ultimately empty tool to make things sound simple and true, even when they weren’t.

Some analysts believe Rumsfeld got the idea from the Johari window, which was being used by NASA and other government agencies at the time. He likely heard about or saw a presentation involving the Johari window. The Johari window already included the concept of knowledge in relation to the self and others. It helps people distinguish between what they know, what they don’t know, and what others know. It also highlights what nobody knows. That’s why the Johari window was created in the first place.

Looking at Rumsfeld’s discourse and actions, the Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek criticized him in an article, arguing that Rumsfeld was undoubtedly trying to bamboozle the public. However, Žižek also pointed out something even more powerful and neglected than the “unknown unknowns”—the “unknown knowns.” Unknown knowns are the things we don’t know that we know but act on every day. For example, ideology. Ideology has long been a central topic for Žižek. Beyond the article I mentioned, he explores this idea in his excellent documentary, The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology. I highly recommend watching it—it’s fun, engaging, and deeply insightful. Watch it together if you can; it’s worth it.

He’s basically explaining or analyzing some very famous scenes in the history of cinema through a critique of ideology. He’s not saying that ideology is something we should get rid of, like some people believe when they assume ideology is always bad. Instead, he argues that ideology is fundamental to who we are. We are ideological beings, so it’s important to understand the ideologies we rely on when we speak or act. That’s essentially Žižek’s contribution to philosophy, communication science, and even design. He even wrote an article about ideology in design.

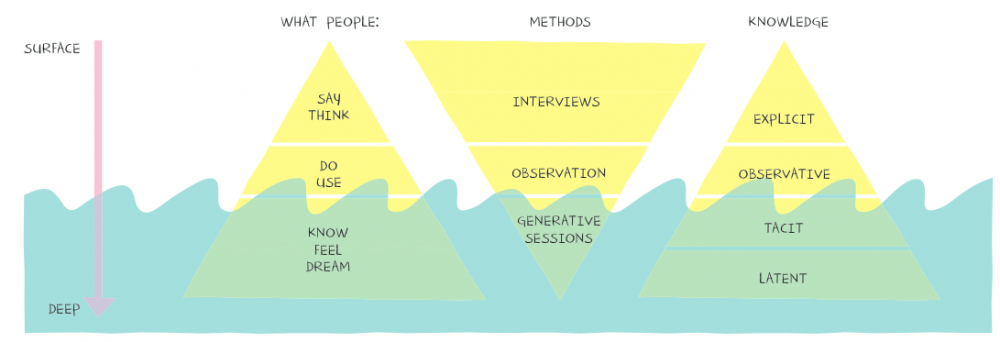

Coming back to our topic, the “unknown knowns” are particularly meaningful for design education because we often rely on tacit knowledge—or unarticulated knowledge. I can’t go too deep into this here, but let me give you a practical definition of tacit knowledge: if I can’t explain why I’ve done something, but I can still do it, I have tacit knowledge of that activity. Unarticulated knowledge means even I can’t put it into words, my knowledge still exists.

Tacit knowledge is even more critical for co-design. There’s an excellent book by Elizabeth Sanders and Pieter Jan Stappers called Convivial Toolbox: Generative Research for the Front End of Design. It’s one of the most practical and insightful books on co-design. The book features a model on its cover that frames co-design as an approach to eliciting tacit knowledge. The authors argue that co-design can help tacit knowledge become explicit or facilitate the socialization of tacit knowledge—transmitting it to others through collaborative making, without it ever needing to become explicit.

For example, when we play games or build things using LEGO or other materials, as we do here in this studio, we’re engaging with tacit knowledge. That’s one of the reasons we use playful materials and approaches: to tap into knowledge that’s not easily articulated in words. Is it possible, then, to support self-management using a tool originally conceived for hetero-management, like the Rumsfeld-Žižek matrix? Of course—it’s possible, provided we appropriate it critically, adapting or hacking the tool when necessary.

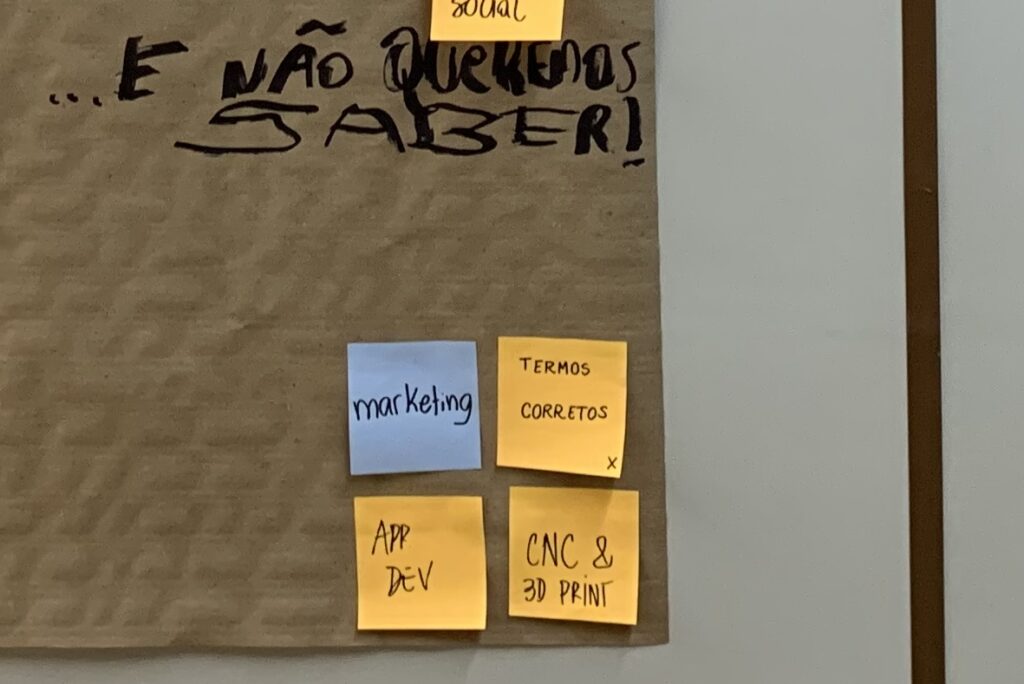

Here’s how we implemented it in our elective. We had a board on the wall that we updated at the end of every class. As we progressed with this matrix, the students decided to add another quadrant. In one corner, they wrote down things they knew but didn’t want to know. They recognized: “We know that we don’t want to know these things.” For example, they didn’t want to know about marketing, app development, CNC and 3D printing, or the “right way” to frame or define what they were doing. These topics came from other sources in their studies, and they felt exhausted by them.

In this particular elective, they could avoid those topics because they had self-management processes in place. At some point, after filling out this board many times, we realized that we knew more as a collective than as individuals. Because each person may have put one sticky note here, but as a collective, we put many sticky notes together. And wow, we have so much that we know that we know. That’s a wealth. That’s abundance. That’s something we can tap into if we need it in the future.

So, we started to hinge on some critical pedagogy principles laid out by bell hooks in her book, Teaching to Transgress. In that book, she says that if someone in a learning community knows something, it doesn’t mean that everyone has to know it or that everyone has to have the same kind of knowledge. What if we think about the learning community as a resource that we can tap into? We can reach out to people in that learning community if we want to learn something new. In that way, everyone can learn and know something different.

It’s a very profound way of thinking about education. Most of the time, education—especially in the banking style denounced by Paulo Freire—tries to standardize knowledge so that everyone has the same minimum basic understanding. That is very violent because a lot of the knowledge that people already have is not recognized as knowledge at all. Students basically have to forget everything they learned before and replace it with the standard curricular knowledge.

What bell hooks and other critical pedagogy scholars like Paulo Freire devised was a way of learning together as a community. That doesn’t mean everyone should know the same things and lose individuality. Instead, the learning community acknowledge that people have different knowledge, and the goal is to reach a point where everyone knows differently. The goal is not to homogenize knowledge.

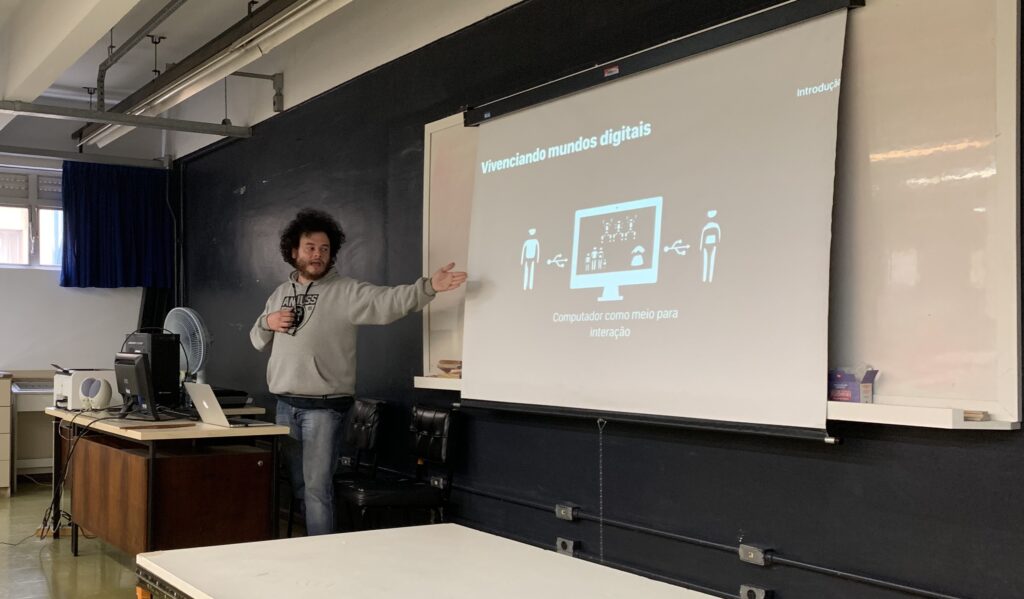

Here’s how we fostered a learning community. Students could take initiative to share their knowledge whenever someone was curious about it through many ways. The simplest was the student lecture. For example, an undergraduate student would say, “Oh, you want so badly to learn this? There’s a student here who knows something about infrastructure.” And then that student would give a lecture on infrastructure.

And, of course, for that student, it was also a teaching experience they were gaining, not in the same way as you’d gain experience if you were a teacher. The person could experience teaching in a lighter way. We often had workshops after those lectures and dialogues. When a professor like me is teaching, I cannot avoid being associated with the authority that this knowledge comes from. But when another student is teaching or giving a lecture, it creates more openings and possibilities for questioning and debating what is being brought to the table.

One of the workshops involved reading and writing a political manifesto about design. We decided to write this manifesto using cloth. We assembled and wove together a parangolé, an artistic fashion item created by Hélio Oiticica to emphasize the importance of peripheral participation in art. The parangolé was also one of the earliest examples of participatory art—not just in Brazil, but in general. Oiticica is very well known in that field. We brought this concept into design as a means to express the necessity of compiling very different political visions together.

When we wrote our political statements—the things we wanted to speak to the world—we noticed that some students were writing things very much aligned with Bolsonaro and his right-wing supporters. These students were also in the class and felt they had the space to speak up. We had, thus, left-wing and right-wing students writing completely opposite political statements. For example, some students wrote things like “Power to the oppressed,” while another wrote, “Doing things correctly,” “Following the rules,” and “Be a nice citizen.” We compiled all of these statements together, and the resulting work became strange as it represented very different ideologies put together. Still that’s what democracy is about. So, we celebrated it.

We even wrote a paper about this because the resulting aesthetics were monstrous—it was very strange. We decided this was intentional, and we liked it. We appreciated the fact that it didn’t resemble modern design at all. You’ve already spoken and discussed this with Rafaela Angelon, the author of that paper, so you know a bit about the background story. Now you’ll learn what happened after the events described in that paper.

After we had the manifesto experience, something noteworthy happened: the manifesto was stolen. The manifesto was placed on a statue at the center of the school, but the next day it was gone. We asked the institution where it was, spoke with security, and even asked the cleaning staff—nobody knew. It became clear to us that someone, guided by political motives, had censored our artwork. This wasn’t vandalism after all—we didn’t destroy the statue. We simply added a thoughtful touch to spark a debate at the campus.

Anyway, we decided what to do next—what kinds of other interventions we would create on campus—that would remain longer. The most important idea that came out of that was establishing a laboratory for new interventions like this one—a metadesign approach. Instead of designing one thing, we would design many things by creating a laboratory.

The students called it COISA, which means “things” in Portuguese, and it stands for Collaborative of Social Innovation and Autonomy. Here, you see a new word entering the vocabulary. It sits alongside social innovation, which was already part of the class title. The students began thinking about autonomy in terms of anarchy and self-management. Unfortunately, the pandemic in 2020 interrupted that process. However, the Design & Oppression network, which was founded in response to the pandemic, reframed—or let’s say drifted—the project in a new direction, focusing explicitly on fighting oppression.

Many students who joined the class in 2019 also participated in the online activities of the Design and Oppression network. Later, they contributed to the founding of the Laboratory of Design Against Oppression (LADO) as a local hub of the Design and Oppression Network. We had marvelous discussions online in our Discord server, and we wanted to bring those kinds of debates, dialogues, and critical making activities to the campus. That’s why we founded LADO. Initially, I worked with Marco Mazzarotto and Claudia Bordin, the other two co-founders of this initiative, to consolidate the laboratory. We shared a room with other activities, and the students who joined the studio critically reflected on how they learn how to learn and design how to design.

At LADO, instead of focusing on specific skills like 3D sketching or “thinking like a designer,” design students developed self-knowledge—knowledge of themselves—which is much more valuable. In self-knowledge, knowing and being are the same, which is an authentic existence: I am what I know, and I know what I am. Now think about the opposite of this: I don’t know who I am, or I know what I’m not. These are inauthentic existences, where you don’t feel comfortable—you don’t feel like you’re in the right place, the right time, the right body, or whatever it may be. Self-knowledge is that moment where you come to terms with your history, the history of your body, the history of people like you, the history of your family, and your people. All of this comes together to help you be yourself all the time.

Out of this reflection—tacitly at the time, because I can articulate it now but we couldn’t then—we ended up designing the Crisis Deck. Some of you have already used it here in our studio. It’s an exemplary project of harnessing self-knowledge in the studio, and it came directly from that elective. In 2022, when LADO was already up and running, this elective became associated with LADO. Every student who subscribed to the elective knew they could collaborate with LADO on their projects. Here, you see a variety of experiments we conducted to better understand and explore the dimension of alterity in design—the role of engaging with the “other” through design—and how the self becomes clearer to the designer when they engage with non-designers or with their own non-designer side.

In the first picture, you see games played with mirrors—specifically theatrical mirrors—using techniques from the Theater of the Oppressed. Then, we visited a social movement incubator and observed their work with the beekeeping movement. Later, when we reflected on Afro-Brazilian religious traditions, Rafaella introduced us to the practice of weaving a patua, a Yoruba amulet. She explained that patua is a way of connecting to one’s ancestry, honoring one’s ancestors, and creating something that ties back to the community and place. We also played a board game about colonization. It was fascinating because it showed how mindsets change when someone has too much power in their hands.

This reminds me of the Squid Game serial and the way people’s behavior becomes mean and selfish due to the rules of the game. It is another example of the impact of design, right? We design those rules. And once again, we’re talking about interfaces. By the end of the course, we started using Lego Serious Play and other materials to explore how we could design something to support critical self-knowledge.

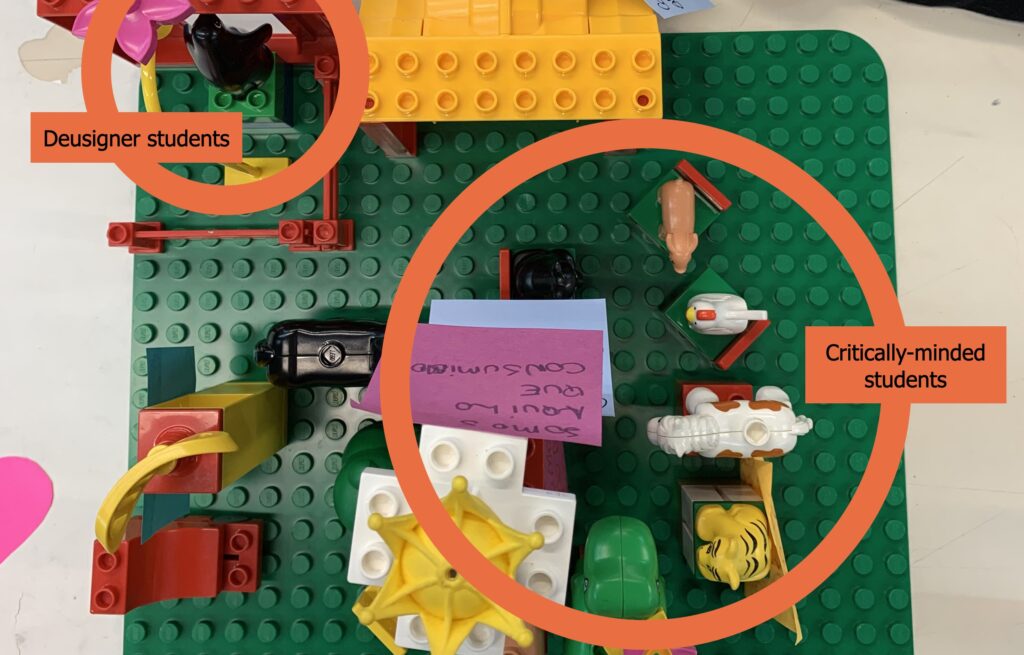

The following slides advances further into what we were modeling. The students discovered that the university does not encourage interaction with “the other.” On one hand, the university acts like a gatekeeper, distinguishing between what is true and false knowledge. All other knowledge traditions outside the university are labeled “non-academic” or invalid. As a result, designers trained at the university begin to see themselves as gods—or deus in Latin. They started playing with this concept and coined the term deusigner, which means a “god-like designer.” It refers to a person who thinks of themselves as an enlightened creative but remains staring at a wall, unable to truly see anything.

You can see the model from the other side—how the penguin humorously expresses this contradiction. The penguin is trying to look out the window, but the university won’t let it read the world. The penguin expresses that contradiction in a lively and humorous way. It’s trying to look out the window, but the university is essentially preventing it by elevating its ego above the eyesight.

The problem with this particular design education program is that while it could entertain the students, those who were critically minded—who understood what was going on and wanted to do something different—were limited to studying design history. They could only analyze what past designers had done against oppression or to create a more just society.

But what happens when you want to go beyond studying history and actually make history now? There was a clear gap. The university was primarily focused on training designers to fulfill roles in industry, meeting the demand for new designers. However, students noticed another demand coming from social movements. The university could show students that they could work with social movements. In fact, there are people earning wages paid by social movements and NGOs. It’s rare, but these positions do exist in Brazil.

The issue isn’t a shortage of positions—it’s that most designers don’t even try to engage with social movements. As part of the democratic process of self-management, social movements need to recognize the importance of having a designer on their team and institutionalize that role. This means they need to hire designers to support their activities. If designers don’t join social movements and advocate for this role, those positions will never exist. Someone has to take the first step.

Students wanted to create a tool to raise critical consciousness about these possibilities. They decided on a card deck, possibly inspired by my own card deck collection and the simplicity of the format. A card deck could be designed within the timeframe available in the course. We started by analyzing the existing card decks in my collection back in Brazil. Today, my collection here in the U.S. is even larger, and I recently bought a new case for it. The meta-toolkit—a toolkit of toolkits—is growing, and there’s room for more additions.

One particular card deck that became especially inspirational for us was a traditional tarot deck. The students were captivated by the images: “Wow, these pictures are so ambiguous and meaningful. They offer so many possibilities for interpretation”. We decided to go for it. If we want to support students in this existential crisis of not knowing what to do—whether to go into industry, join a social movement, start a new company, or something else—they could use this card deck during their senior year.

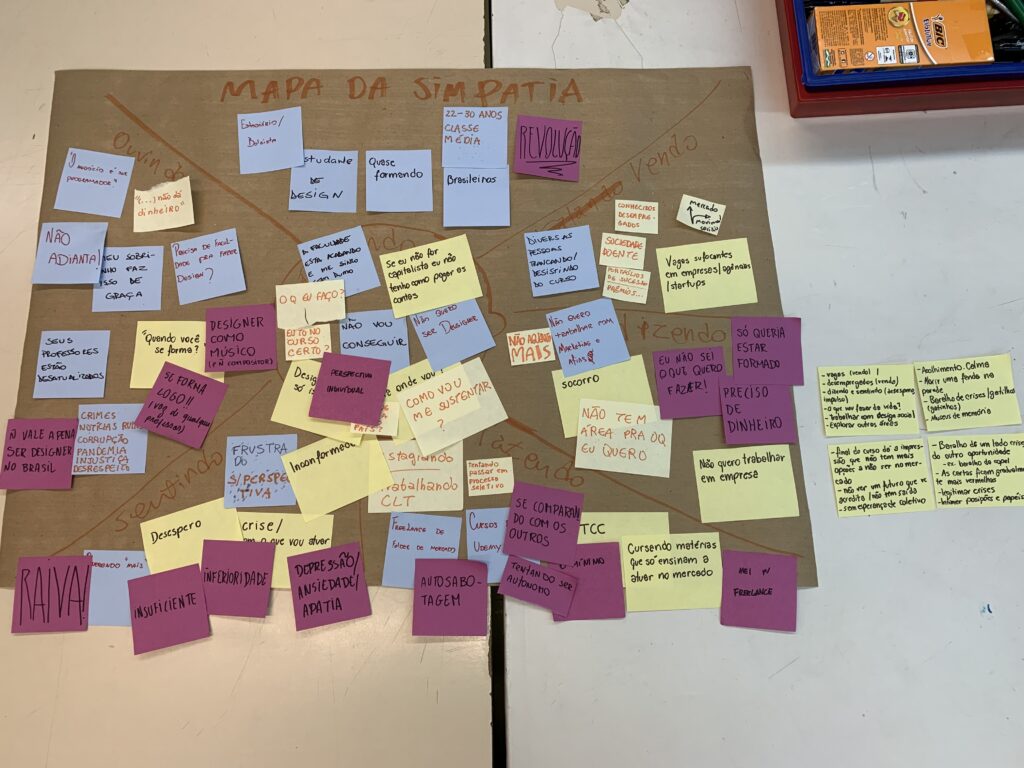

The students began by interviewing their colleagues and peers. They organized the interview data using the sympathy map, which is an altered version of the empathy map—one of the most famous Gamestorming activities. Empathy maps are commonly used in design research, design thinking, UX design, and similar fields. They focus on designing for the other. However, in this case, the students were designing for themselves. That’s why empathy wasn’t the best framing. They reframed it as sympathy, focusing on what they had in common instead of emphasizing differences.

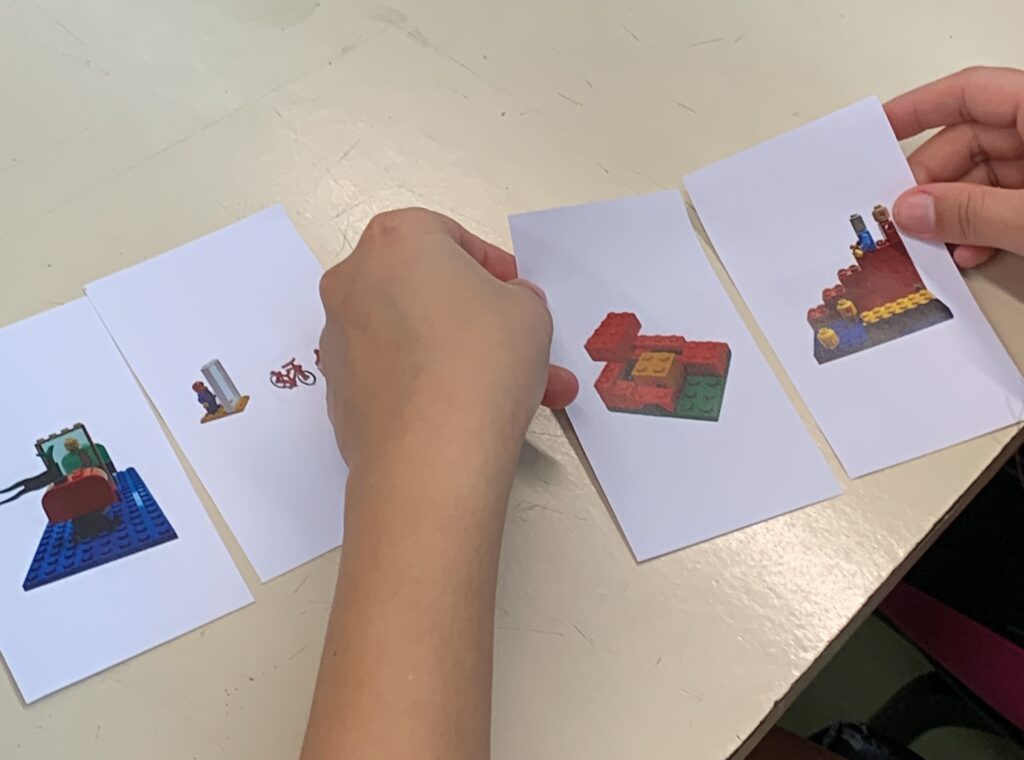

Afterward, the students modeled the most common crises they identified in the sticky notes using Lego Serious Play. Although I had the Duplo system available, I preferred to use traditional small bricks because we needed detailed expressions for this activity. The students were essentially prototyping images. The goal was to create images that, just by looking at them, would convey a sense of the crisis—giving viewers an ambiguous yet meaningful feeling, similar to the effect of tarot cards. We prototyped and photographed these images in a single session that lasted almost three hours, which is incredibly fast for a co-design project. By the end, we had a prototype that we tested the following week.

An important feature of this card deck is that it has two sides. Each side represents one aspect of the crisis, and you’re supposed to flip through the cards, explore the oppositions between the two sides, and figure out what they mean for you. Once the card deck was complete, the students began testing it with other peers—senior students who weren’t enrolled in the class. I also started using it in my supervision activities. Whenever a new student started a project at LADO—particularly their final work—I would use these cards. The cards helped students think about an existential crisis they were experiencing at the time and encouraged them to design a project that would either fulfill or help them overcome that crisis.

The goal wasn’t just to address their own crises but to connect with and help others who were experiencing similar challenges. This allowed students to identify with like-minded peers or those in similar contexts. This process is somewhat akin to asking questions about positionality, but in this case, the focus was on a specific shared contradiction. Two students who participated in the tests as subjects later asked about the project. They said, “Hey, Fred, is this project still going on? Who’s going to finalize the prototype?” I told them, “Well, the students who started it are gone. The semester is over. Would you like to pick up the project and continue?” They were excited: “Wow, great idea, let’s do it.” Since it’s an open-source project under Creative Commons, they could actually continue the design.

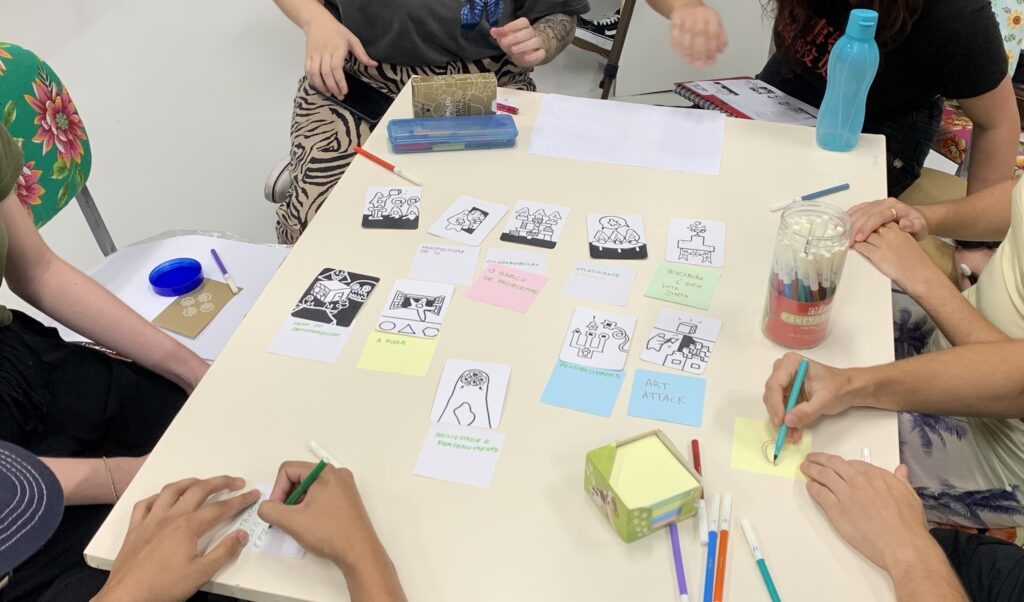

They began sketching many alternatives—forms and shapes to convey the same messages—instead of relying on the Lego pictures, which were cumbersome. Slowly but surely, they developed a visual language. They drew heavily from icon design and principles of information design. Then, they went back to other students who hadn’t participated before. They organized a workshop where they discussed the cards and created a kind of pedagogical approach to reflect on shared existential crises.

They didn’t assign names or labels to the cards but were interested in the kinds of labels students came up with for the images. These labels changed after they watched the session recordings. As you can see, the research became more rigorous when they took over. In 2024, last year, they published a paper about this crisis deck. The paper detailed the history behind the project, including its roots in critical pedagogy and the Theater of the Oppressed. This card deck is now part of our meta-toolkit here at the MXD studio. Some of you have already used these cards.

I encourage you to try them out. In a minute, I’ll show you where they’re stored. It’s not a finalized project—there’s still work to be done. For example, the deck currently includes only 10 crises, but more could be added with additional research. It could also have a better finish. This is an open-source project, so you’re welcome to continue developing it if you’d like.

I also took these cards to the DRS 2024 Boston Doctoral Consortium, where I gave a keynote on existential crises as a doctoral researcher. At the end of my talk, I presented the card deck as an example of a tool researchers could use to find a fulfilling topic—one that leads to self-knowledge, not just academic knowledge. I explained that this wasn’t about producing knowledge that ends up in a library without impact—it’s about knowledge that changes your life in some way. Interestingly, I asked the audience, “While looking at these cards, please stand up if you feel like you’re undergoing such an existential crisis.” It turned out that one card, in particular, was very popular.

To wrap up: the self-managed studio produced self-knowledge. Students realized they weren’t just individuals; they were also part of a collective design body. When I say self-management, I’m not talking about individual management. I’m talking about the self as us. This is the foundation of practice behind self-conscious design—or designing the self in and for itself.

Now, I’m being very Hegelian here, so it might be difficult to understand what I mean. But that’s okay. If you repeat it in your mind many times, you might eventually get a different meaning from it—and that’s fine. Designing the self in and for itself means moving away from designing the other for another. Who is the “other” that we usually design for? The user. And who is the “another”? The manager.

In a hetero-management system, we design users for managers. Essentially, we’re helping managers exploit users. But in self-conscious design, we design in ourselves for ourselves, fully conscious of who we are. That’s what it means. Diagrammatically, this can be conveyed as follows: there are interfaces at the center, workers on the top and bottom, and users on the left and right.

You might ask, “Where are the designers? How should we position ourselves in self-management and self-conscious design if there are no place for designers?” In self-management, designers create interfaces as workers. That’s already well established. If you want to join self-management as a boss, you haven’t understood what it’s about—you need to be a worker to engage in self-management. Similarly, in self-conscious design, designers create interfaces as users. All right, folks. You can check the references later if you want to explore these ideas in greater depth.

References

CrimethInc. Work. (2011). CrimethInc.

Bonsiepe, G. (1999). Interface: An approach to design. Jan van Eyck Akademie.

Chaplin, Charlie. Modern times. Beverly Hills, CA: United Artists, 1936.

Gonzatto, R.F., van Amstel, F.,and Jatobá, P.H. (2021) Redesigning money as a tool for self-management in cultural production, in Leitão, R.M., Men, I., Noel, L-A., Lima, J., Meninato, T. (eds.), Pivot 2021: Dismantling/Reassembling, 22-23 July, Toronto, Canada. https://doi.org/10.21606/pluriversal.2021.0003

Bizotto dos Santos, W.B., Mazzarotto, M.,and Van Amstel, F.(2023) Learning design as a human right: the beginnings of a design lab founded on critical pedagogy, in Derek Jones, Naz Borekci, Violeta Clemente, James Corazzo, Nicole Lotz, Liv Merete Nielsen, Lesley-Ann Noel (eds.), The 7th International Conference for Design Education Researchers, 29 November – 1 December 2023, London, United Kingdom. https://doi.org/10.21606/drslxd.2023.104

Gray, D. Brown, S. and Macanufo, J. (2011). Gamestorming. O’Reilly Media.

Rumsfeld, D. (2011). Known and Unknown: A Memoir. Sentinel.

Luft, J., & Ingham, H. (1955). The Johari window, a graphic model of interpersonal awareness. Proceedings of the western training laboratory in group development, 246.

Žižek, S. (2006). Philosophy, the “unknown knowns,” and the public use of reason. Topoi, 25, 137-142.

Elizabeth, B. N. S., & Stappers, P. J. (2021). Convivial toolbox.

Hooks, B. (2014). Teaching To Transgress. Routledge.

Angelon, R., & van Amstel, F. (2021). Monster aesthetics as an expression of decolonizing the design body. Art, Design & Communication in Higher Education, 20(1), 83-102.

Zukowski, Alanis Louise de Mello; Kosake, Maria Vitória Ribeiro; Amstel, Frederick Marinus Constant van; “Codificação gráfica de crises existenciais: reflexões sobre um experimento de educação crítica em design”, p. 1756-1763 . In: Anais do 11º Congresso Internacional de Design da Informação e 11º Congresso Nacional de Iniciação Científica em Design | CIDI+CONGIC 2023. São Paulo: Blucher, 2024. https://doi.org/10.5151/cidiconcic2023-121_649945