Abstract: In Experience Design, we typically learn to design experiences for others, the users. While drawing this distinction between us and them, we block the potential to change who we are by designing for ourselves. Radical alterity means including the Other as part of the Self. It is a concept crafted on decolonial Brazilian anthropophagic tradition, which can be summarized as incorporating foreign ideas through critical digestion. This panel presentation shares the attempt of overcoming the “us and them” relationship by forming collective design bodies that welcome difference and dissensus in participatory design processes.

Presented and recorded during the Inclusive Design panel organized by the ACM International Conference on Interactive Media Experiences (IMX 2021). After the panel, we had a great informal conversation while eating virtual food on the Oh-Yah platform provided by the conference.

Slides

Audio

Full transcript

Thank you, Kate. Thank you, Vino, for the invitation to join this panel. First of all, I would like to provide a bit of contextual information. Where do I speak from? I speak from Brazil, a country that has been going through a terrible political and economic crisis, and now also a health crisis due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

As a result of that situation, at the university, it is difficult to secure funding and opportunities to experiment with cutting-edge technologies for interactive environments like those we are using now. Additionally, there is political uneasiness around certain topics, especially those I will present here.

I don’t have much time to delve too deeply into this background, but if you know a little about Brazilian politics and economics, you might understand why I have chosen this topic to share with you. These are some recent reflections I’ve been having about inclusion and why we should take a more radical approach—one that I call radical alterity.

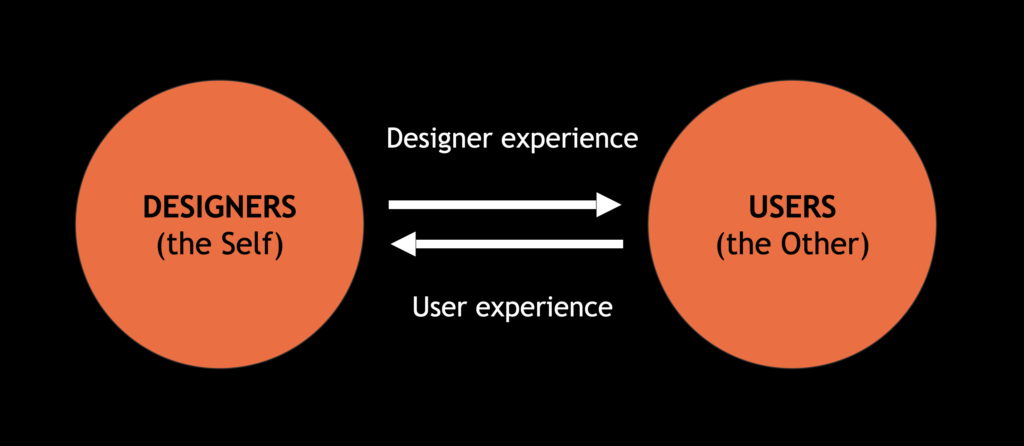

The concept of alterity comes mainly from anthropology. It is also referred to as otherness. If we apply this to experience design, my main field at the university, we can see a division between us and them.

In our case, us refers to designers, and them relates to users. We design experiences for users, but we also must consider that users’ experiences differ from designers’ experiences. Through a process of exchange—which is precisely what design is—those experiences transform.

However, most of the expectations for change are placed on the user. Users are expected to change, while designers are expected to help, guide, or sometimes even steer their behavior. But we, as designers, do not expect to change ourselves. This is a colonial version of alterity where the colonizer remains the same.

What I propose to my students and to any practitioner is to take a more radical approach—one in which, instead of just changing users, designers also change. It means including users in ways that enable them to change the designers themselves.

Radical alterity in experience design means including the other as part of the self. Instead of treating the user as an abstract person—such as a persona based on qualitative or quantitative data you have gathered on the field—you actually bring the users in as actants, as agents, as powerful people, just like professional designers.

And then users may also transform into designers. We have now a collective design body —some formally trained, others who were historically unrecognized as designers but are now acknowledged. This happens because we are genuinely and concretely including these people.

That’s conceptually what radical alterity means. And it draws from the long anticolonial anthropophagic tradition in Brazil. It started 500 years ago when the Portuguese arrived on our coast, and Indigenous people loved them. They admired the Portuguese. They loved the way they spoke, the way they dressed, and the way they talked about so many things they had never heard of. They ate them and incorporated their strength into the tribe in an honorable ritual.

This ritual is not practiced literally in Brazil today, but metaphorically, it still happens. This is one of the most important tropes for understanding Brazilian culture—how Brazilian culture relates to foreign cultures, and how it assimilates them through digestive and reflective criticism. In a way, we are creating this radical alterity concept based on the anthropophagic tradition of incorporating the other into the self

What is strange is different and exciting. Interacting with the stranger means changing yourself.

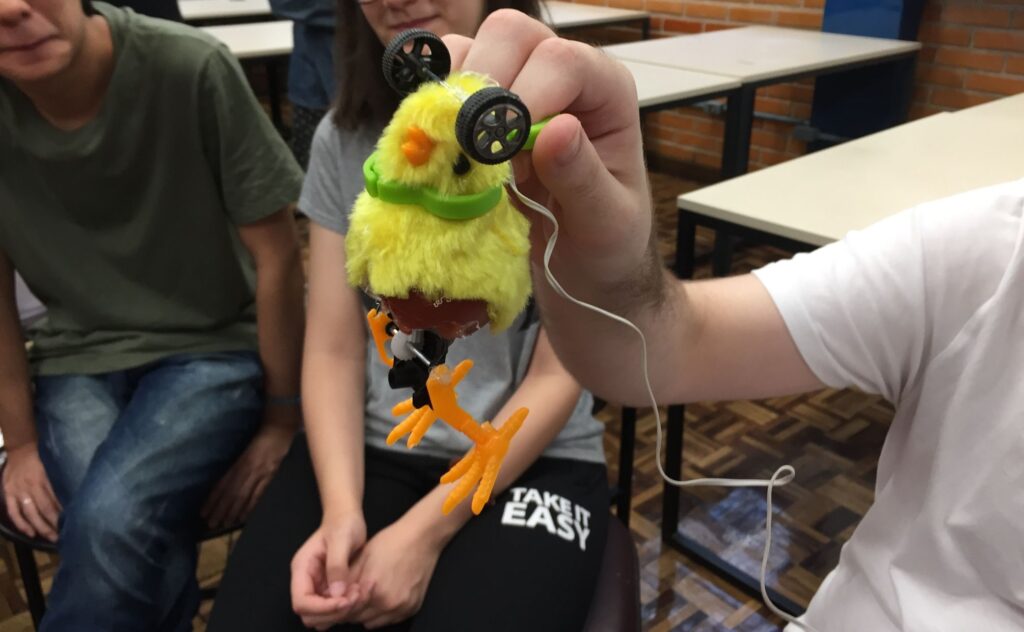

I will show some examples of design practices inspired by radical alterity. For example, in this picture, you see a gambiarra, a clever solution to a situational problem using only what is already available. It’s a quick, improvised solution with the least amount of resources and a way of expressing your identity. A gambiarra differs from prototyping because you’re not just prototyping an object. You’re also prototyping yourself because it’s an act of showing your identity, as I mentioned.

In this case, the students showed their thoughts about driving—how robotic agents could interact with human drivers and how they might have meaningful conversations about ethical dilemmas, like who would die in a car crash and whose life should be prioritized. This is the minimal amount of materials we need to have such a conversation to disclose the design.

What we teach from this embodied understanding of design is that design should not be learned from the outside, from books, or foreign countries. It should be learned first of all from our own environment, from our own situation, and from all the materials we have around us.

In this simple exercise, students learn how to do this by selecting materials they find around their homes or at the university. Then, they use these materials to stimulate another person listening to music.

They stimulate the person by rubbing the materials, scratching them, or bringing clothing to the skin—something hot or cold. These movements are synchronized with the music to show the student’s interpretation of the music. It’s called augmented music.

The listener can reflect and later share what they felt. Then, the designers change the interpretation repeatedly because it’s an iterative process—not just designing the object but also changing your perception of who you are and what you think is meaningful in music. Students not only learn to understand different perceptions, music tastes, and opinions but also to understand the historical situations in society. They realize that they are also part of oppressed social groups.

Design is not just a professional field that leads to power but also a way to see that you are part of other people and other groups. We use cultural probes, which are typically used to understand the user, but here we use them for designers to learn about themselves and their environment. We also work a lot with the Theater of the Oppressed, and we have adapted it into Theater of the Techno-Oppressed,

where technology is played by a person. This acting scene shows, for example, the biases in social networks that try to exploit emotions—people’s frustrations with the feeds they open,with their hearts being exploited by advertisers.

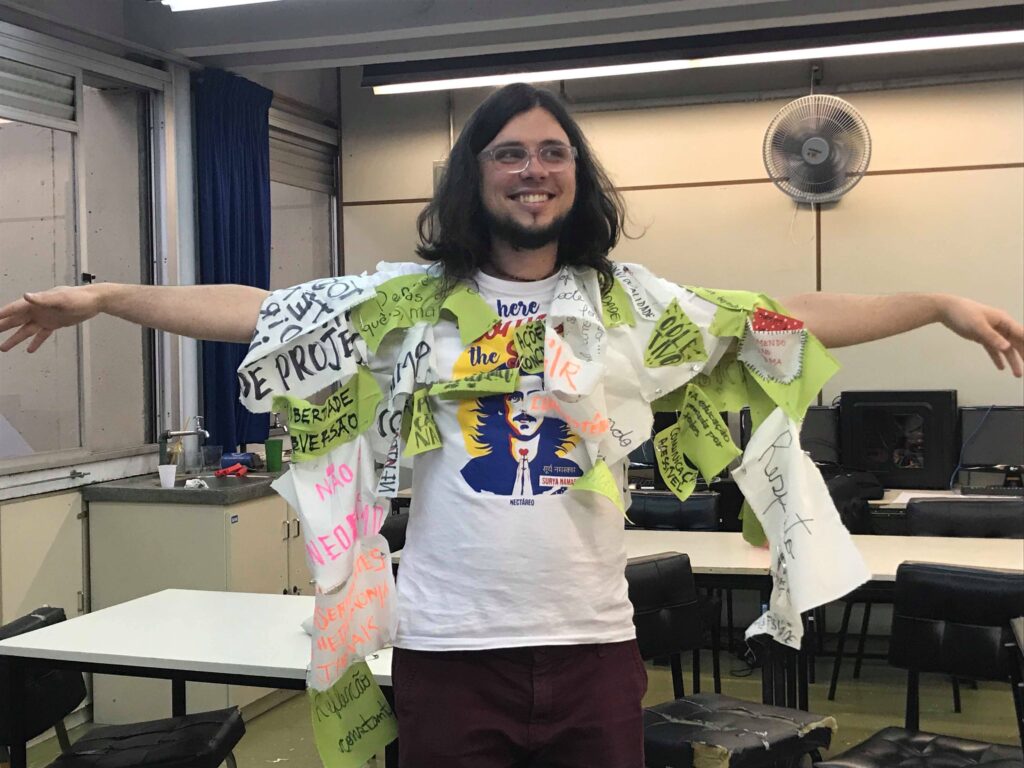

The major takeaway from this short talk is that the radical inclusion of the other leads to designing experiences for ourselves, not for others. That’s an entirely different way of looking at design because we don’t need big states or multinational companies to design and serve our needs. We can do that through bottom-up or horizontal organizing design bodies that welcome differences and dissensus.

So it’s constantly changing, completely different from Hobbes’ Leviathan and any situation with a prominent design leader, a genius who leads the crowd. Instead, we have a bottom-up approach, where some people represent the wishes of their collective, and they are always putting themselves into check.

Then, democratically, we can decide what is best for us, like I am doing with my students and the wearable manifesto they let me wear, which displays their wishes about the future of design, education, and practice. Thank you very much for listening. I look forward to a great discussion next.