Abstract: Design used to be about expert designers designing complex entities for society. Now, increasingly, design is about designing emergent performances among designers and usigners. Emergent performances include experiences, interactions, and any emergent relationships that unfold through time. Since they cannot be controlled, design can better learn from performance arts how to provide minimal improvisational structures. Once visible, these structures can be used to redirect the course of impending societal changes. The case of Generative Artificial Intelligence is a case in point. How is design going to react to its reductive biases?

This is a post-recorded lecture from the MXD Spring 2024 Graduate Seminar, University of Florida.

Video

Podcast

Full transcript

This is supposed to be a historical, personal, and analytical account of what I see going on in design research, as well as in general in society—some cultural-historical changes shaping design towards emerging performances. In this presentation, I aim to expand my current understanding of design as a product feature, as something intrinsic to objects and things in the world, like this AirPod package. However, design is not just the industrial activity that produces the AirPod package. Design is not just a professional activity that structures the relationship between hearing, sound, and music, influencing competitors’ designs.

Design, as I’m trying to conceive through these concepts of emerging performances, is a history-making activity—a human activity that projects designable objects into the past and into the future. To get into emerging performances as a design object, first of all, I need to rethink what design is because it doesn’t currently fit understandings of design that reduce it to professional, industrial, or product-related activities.

Designable objects change because they are historical through and through. Design produces things in particular historically situated situations—not just in a certain place or culture but also in a specific history. These objects change because they play roles in significant cultural-historical changes. That’s why they are historical through and through—being in history and transforming history. That’s the raison d’être, the reason why these objects exist. They have a purpose.

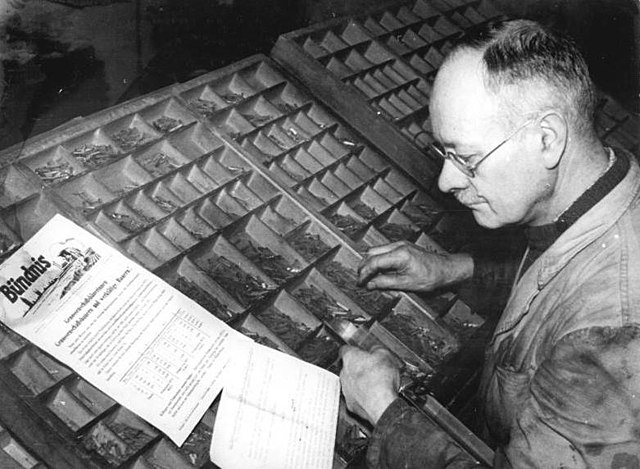

For example, if you look at this picture, you may wonder what this person is doing if you’ve never engaged in this activity. This person is a typesetter, and in the 1950s, he used the tools available to compose a page layout for mass production with printing press techniques. The typesetter was doing something that graphic designers typically handle today. Many typesetters lost their jobs once printing became automated, especially after desktop publishing became available.

In other words, designing on the computer and producing with an electronic printer seamlessly eliminated the need for this intermediary. But the typesetter wasn’t just a middleman—he added skill to typography and page composition. Layouts were created with much more care at that time. This object of design—the typeset page layout—has become invisible to us now because of technological and job replacements. However, at the time, it was a clear design object.

In the 1980s, some Scandinavian participatory designers tried to address this transition more humanely. Instead of designing digital desktop publishing systems that would make typesetters’ skills obsolete, they integrated this knowledge into graphic user interfaces. This led to one of history’s first desktop publishing graphic user interfaces. They made some exciting progress, and some ideas from the UTOPIA project and the TIPS software were incorporated into later software like Adobe InDesign and Photoshop. These are, in a way, the ancestors of today’s Photoshop and other tools for manipulation and publishing.

In the 1990s, something different was happening. Design started to act as a glue between various disciplines. For example, you see a multidisciplinary design team working on a project in this picture. However, you don’t see the object they are designing as clearly as before. In earlier examples, like page layout, you could see the design object directly. Now, the screens show many images, most of which are not about the object but the context surrounding it.

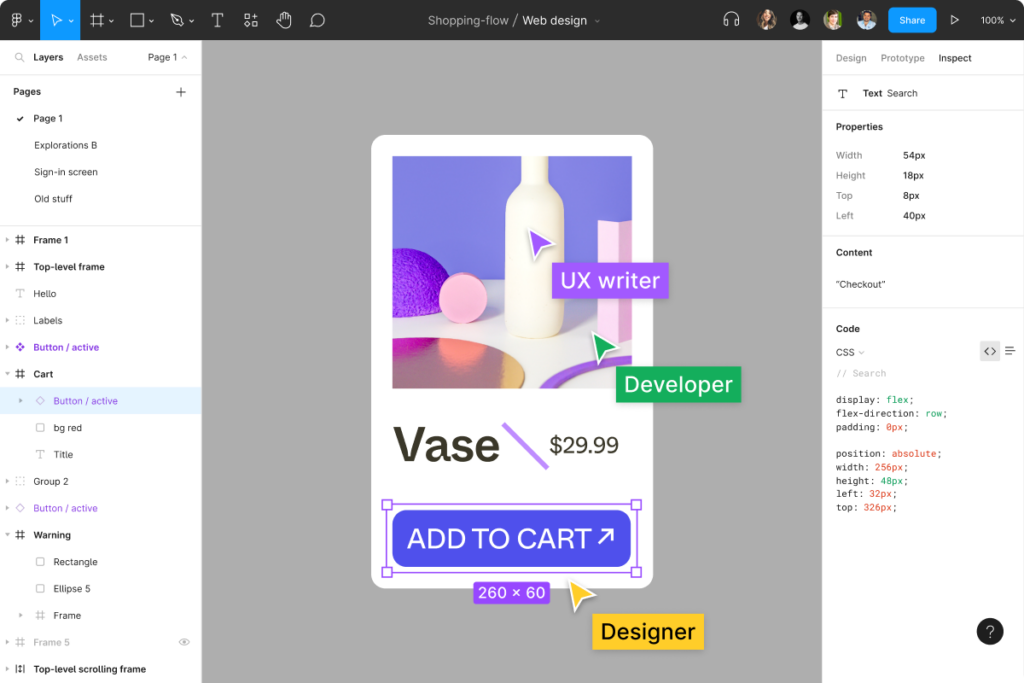

In the 90s, design expanded beyond product or desktop design, and computer graphics shifted focus from the interface towards interaction—something bigger. Nowadays, this trend is much more consolidated. We now have terms like UX (User Experience) that didn’t exist in the 90s. UX writers, developers, and designers might even share a platform to co-design these experiences and workflows using different graphic representations—structural, visual, or high-fidelity.

We see new objects of design emerging—sometimes more tangible, other times less so. But it’s not about whether these objects are tangible or intangible—it’s about the tools, concepts, and theories we use to grasp them. As our understanding improves, they become more tangible to designers, who often design these new objects to meet professional demands. Sometimes, they also reflect on why particular objects become designable in the first place.

A recent report, The Expanding Scope of Design, produced by Other Tomorrows and Swissnex, summarizes interviews with designers, mostly from Europe, the U.S., and Australia. This report reflects a Global North perspective on the current state of design. It confirms that design is expanding and now involves issues like technology, gender, race, power, politics, culture, climate, and economics—areas beyond the traditional graphic or industrial design scope.

However, while the report identifies new demands, it doesn’t fully explore the social forces driving design to engage with these issues. In academia, the process of identifying these forces is usually slower. In my 2015 PhD thesis, I tried to offer a general design object theory. It was pretty preliminary at that time—I didn’t yet have a complete picture of the field. Now, nearly ten years later, I can update those initial ideas after working at different universities in various countries with other students and professionals. This lecture is meant to provide those updates.

Back then, I explained how the object of design expanded from construction materials to emerging performances driven by contradictions within design activities. My theory posits that design objects evolve when these contradictions become too intense. These tensions do not arise from design activity alone but emerge from networks of interconnected activities. Emerging performance—my focus now—only became perceivable around the 90s. The earlier example of a multidisciplinary team shows this shift: they were not focused on a single industrial product but on experience and interaction as part of the product.

Design constantly tries to catch up with these expanding objects as a professional and academic field. Theorizations, including mine, tend to lag what is happening in practice. Society often moves faster than our conceptual frameworks, though theorizing remains essential to guide the next steps. Visualizing this process more simply: in the 1980s, the focus was on complex entities like industrial or graphic design objects. From the 90s onward, new disciplines emerged, such as UX design, interaction design, and service design. These disciplines deal with fuzzy, intangible objects—what is an interaction? A service? Information?

“Product design” today often refers to software marketed as products, creating conceptual confusion. This shift highlights how design has moved from focusing on space—like in industrial or graphic design—to focusing on time—how things evolve. This transformation has profoundly affected how designers position themselves. In the past, designers would manipulate objects through tools like 3D modeling software or Photoshop, creating physical or digital products intended to change user behavior. Users had a more passive role back then.

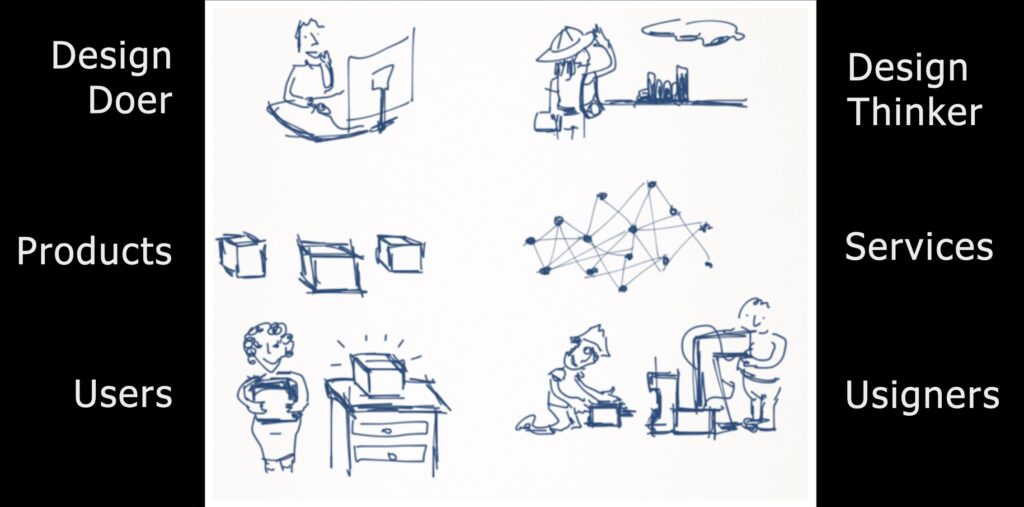

With emerging performances, users now act as co-designers, participating synchronously in workshops or asynchronously by modifying source code. Modular systems allow users to play a significant role in creating experiences and interactions, blurring the boundary between user and designer. I call these participants usigners—a hybrid of user and designer.

Today, designers—or “design thinkers,” in contrast to “design doers”—focus on services and systems. While products may still serve as touchpoints, the primary design objects are infrastructures and networks that enable coherent experiences. This shift reflects a post-industrial focus on mass customization, co-creation, and value generation in service design, experience design, and other related fields.

These trends often originate in industry, but academia is critical in anticipating what lies beyond service or interaction design. We’re not just describing where design is now—we’re shaping where it will go next. We try to make sense of things more fundamentally and essentially so that we don’t get dragged by these trends or buzzwords suddenly replaced by other ones. We try to focus on more constant things that will remain with us for a longer time, so we don’t spend critical public resources researching something that won’t last for long.

Emergent performance tries to grasp all these new things into one shared object. The most important characteristic, and the difference between past design objects and this one, is that it is shared with usigners. In the past, designers would design an object and deliver the complex entity to users, citizens, or whoever they were targeting. But an emerging performance cannot be delivered—it has to be enacted, and every time the performance happens, it unfolds differently. Performance is a process, not a product. It is intangible but can be measured, and it can be planned, but it remains emergent. You cannot fully control it.

I tried to convey these findings through my PhD research in healthcare design in a fun way, using a board game called The Expansive Hospital. This board game is a semi-cooperative game about designing during an emergency. You have to grow the hospital while the patient queue keeps changing, so you never know precisely what the demand will be. New patients may arrive unexpectedly, and you must quickly build the hospital to meet those demands, deciding whether to admit patients or transfer them to another hospital.

It’s a challenging game but also very competitive, as each player has a different way of earning money and competing to become the richest. However, if players act too individualistically, the hospital goes bankrupt because there needs to be some minimal shared interest for the hospital to work. If each player focuses only on their gain—just like multidisciplinary experts working on a hospital—then the design won’t work, and the hospital will fail. This reflects the contradiction between personal and collective gain, central to healthcare management.

After completing my PhD in the Netherlands, I ran a cross-cultural validation of the game at a university hospital in Brazil to see if the structure and concepts I developed would also apply to Brazilian healthcare. To my surprise, I found that the healthcare professionals in Brazil were facing the same kind of contradictions as those in the Netherlands.

After playing the game, they realized the importance of collaboration despite their differences. This opened the possibility of playing more open-ended games to address specific, concrete issues they were facing. The Expansive Hospital sensitized participants to contradictions between their contributions and the system. Afterward, they engaged in storming activities like empathy maps, collaborative planning views, priority radars, scenario planning, and changing darts. We created some of these activities, while others we adapted from existing gamestorming techniques. In just a few months, these activities transformed some conflicts that had previously blocked team communication. Conflicts that created resentment were reframed as opportunities for innovation. The teams learned that conflict could be positive if well-managed. This insight became the foundation for “planning for change” or “playing for emergence.”

At first, planning was seen as a rigid, bureaucratic process where everything had to be specified beforehand and executed exactly as planned. However, through these games, healthcare practitioners realized that their planning needed to be flexible. Emergencies are so central to healthcare that rigid rules quickly become irrelevant. The rules needed to be abstract and adaptable to avoid overly structuring their activities.

This approach extended beyond healthcare. Later, we discovered similar challenges when I worked with a utility company. Although the company was not in the healthcare sector, it faced contradictions in emergency planning. We began by focusing on planning but soon realized that we needed to shift towards designing strategies, tactics, interfaces, and processes—concepts better conveyed through design than traditional planning.

In the Brazilian context, design feels further from control than planning does. We explored various ways of representing contradictions and shared these publicly through animations. These animations attracted young entrepreneurs interested in working with the utility company to develop a smart grid. The company wanted to move away from centralized energy production and towards decentralized production, enabling smaller companies to produce and distribute energy in new ways.

This marked the beginning of our concept of designing for emergence. Designing for emergence means creating space for many possibilities, including unexpected and even seemingly impossible ones. Emerging performances often generate surprising outcomes—unexpected ways of delivering services or co-creating new experiences. These outcomes can lead to social innovations, new businesses, or spin-offs.

In the past, once a complex object was delivered, it was considered complete, even if it wasn’t used. However, an emerging performance only becomes real when it happens in the world. From that initial complexity, further complexity emerges, producing unexpected outcomes. We see similar processes, such as bird flocks preparing for migration. Birds rehearse collective flight patterns with no single leader. Instead, each bird follows simple rules, creating complex group movements together.

In the 1980s, Craig Reynolds modeled this behavior with a computer simulation called Boids (Bird Androids), which recreated the flocking behavior of birds. This work inspired me to conduct similar experiments with my interaction design students at PUCPR in 2018. First, students simulated Boids using their bodies. Then, they created a conditional design script. The students wrote simple rules for interaction, and another group executed them. When they compared the results, they realized the outcomes were not exactly what they had planned. This demonstrated that interaction design isn’t just about the screen; it’s about the interactions between people and their environment.

These experiments showed that small changes in rules could reshape interactions, just as birds adjust their flight paths to avoid obstacles. Emerging performances can’t be predicted or controlled, but they can be prospected and negotiated. Design is always intentional, but intention doesn’t have to be singular. Multiple intentions can be articulated and negotiated, and that’s what design is about.

I want to share an example: Suru, a modular furniture system developed by my students Conrado Dembinsky and João Victor Tarran Araújo. They were interested in open design—design livre in Brazil. Their idea was to allow furniture to evolve with users, adapting to different stages of life. They didn’t try to design the whole system from the top down. Instead, they created a basic module that could be combined in many ways. Later, they explored adding other modules to connect with the original one, opening new possibilities for assembling furniture. Once Suru was introduced, it began to evolve on its own. Others started imagining new ways to use it, including for improvisational parties. We tested the idea by assembling DJ tables on the spot and adapting the furniture to fit the event.

These experiences taught the students that design must follow the process of emergence rather than trying to control it. They even rode through the city on bikes, carrying the modular pieces and setting them up in different locations.

Designing for emergent performances can also be explored through performance-based arts. Capoeira—a Brazilian martial art disguised as dance—has been particularly influential for me. I learned capoeira during high school, and it helped me navigate bullying and connect with my Brazilian identity. Capoeira emerged during colonial times as a way for enslaved Africans to preserve their martial arts skills by disguising them as dance. Although outlawed for a while, capoeira became an iconic cultural activity of Brazil.

I also practice Hindustani folk music, Bhajan. Bhajan, like jazz, involves improvisation. There is no fixed structure—participants adapt their contributions in real time. This kind of collective music-making reflects the principles of emergent performance, where unexpected elements shape the outcome.

Later in my life, I became interested in Theater of the Oppressed. That was when I realized that those two worlds, design and performance arts, were not disconnected in my life. The Theater of the Oppressed aims to change the world through theater, where you rehearse reactions to oppression, much like redesigning something. We started experimenting with Theater of the Oppressed in design. I have other papers and talks about this, so I won’t go into too much detail here.

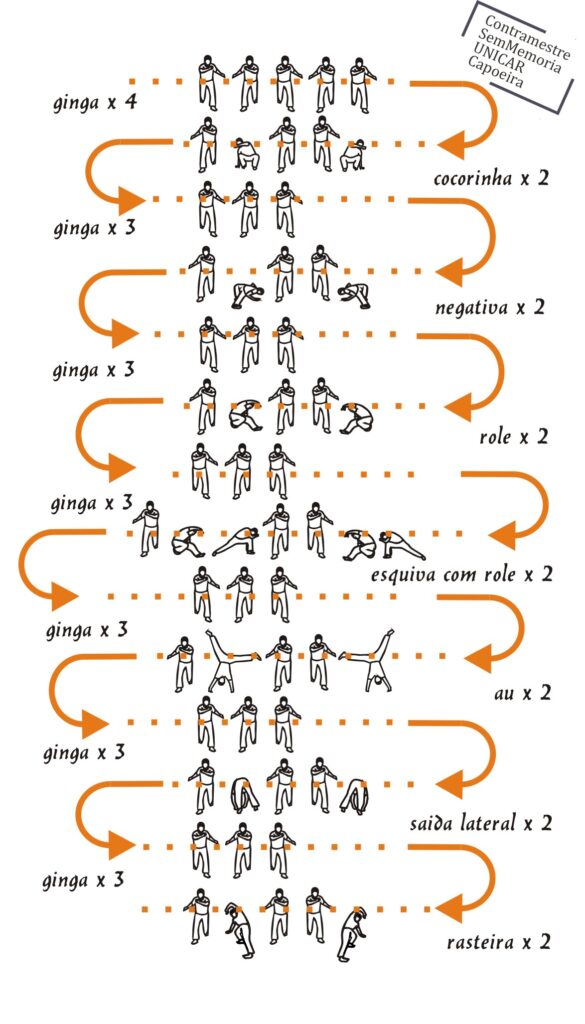

Any of these performance-based arts have common, basic movements—recurrent movements that form the foundation of improvisation. In capoeira, that movement is called ginga. Ginga is the movement where you go back and forth, alternating your legs, so you never stand still—you’re always in motion. If you keep moving, you’re in a better position to perform the next move. Every movement in capoeira responds to an opponent’s move. You never start a movement alone; it’s always a response to what came before.

There’s also the initial seeding movement that capoeira players do when they enter the roda, the circular space where they play or fight. As you see in this picture on the left side, ginga is a pathway to movements like cocorinha or negativa—moves a player might use to respond to their opponent. Returning to Ginga repeatedly keeps the capoeira player ready to engage in emergencies.

The beauty of capoeira comes from this continuous movement—everything flows from ginga. If an opponent comes to hit you, it’s easier to keep moving rather than trying to start a new move from stillness. You take advantage of inertia, giving yourself a better chance to change direction. This constant motion is essential for subversive activities.

Now, let’s look at a concrete example of designing for emergent performances—something we don’t want to stay the way it is. Let’s discuss generative AI. I’ll provide some criticism of how generative AI is being used in design and some alternatives for how we might regenerate AI.

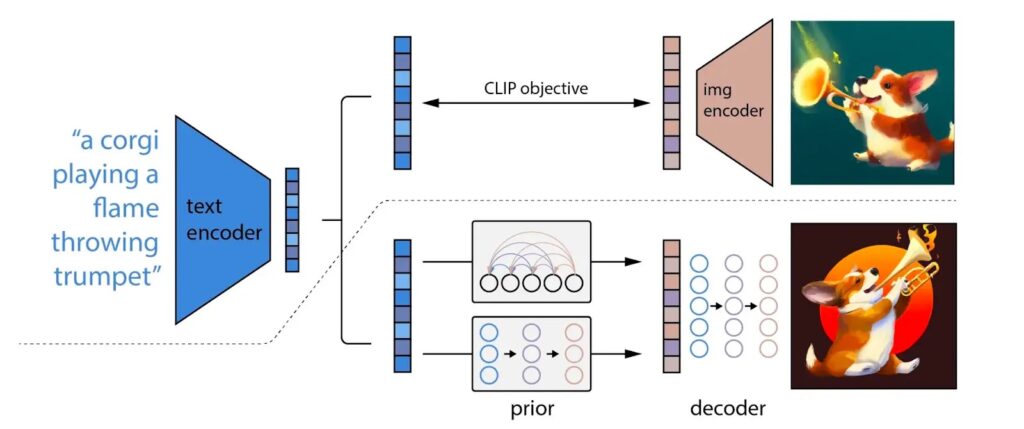

Generative AI relies on complex algorithms—not simple rules—and these algorithms are so difficult to understand that most people don’t know what’s going on. You type a prompt and get an image; even if you use the same prompt, you’ll get a different result every time. I don’t know all the technical details, but I can see these diffusion algorithms draw from countless indexed images. They don’t just combine pictures like a collage—it’s a much more sophisticated process that produces different outputs every time.

The randomness in generative AI relates to how we give meaning to the words in our prompts. However, many people use it like a ready-made product—press a button, get an image, and repeat until they get the desired result. This reduces design to a complex entity. Prompt engineers aren’t designing emergent performances because once the object is generated, it becomes fixed and static. You can look at and admire it, but it doesn’t interact or change—it’s not an emergent performance.

I see AI as a reductive technology that risks making us lose cultural richness—something we have collectively built over time. I worry that if AI continues in its current form, it will drive design back to complex entities and even further to construction materials. This is speculative, but if we continue consuming energy and resources at the current pace required by AI, we may need to rethink computer production altogether. At some point, we might need to ask whether making computers with silicon chips is sustainable. If not, we could return to design rooted in construction materials.

However, there are ways to expand design towards emergent performances without giving up the progress we’ve made. Developing critical consciousness allows us to resist reductionism and guide AI toward enabling emergent performances. The challenge is that many designers focus more on how to design with AI rather than on why these design objects are emerging.

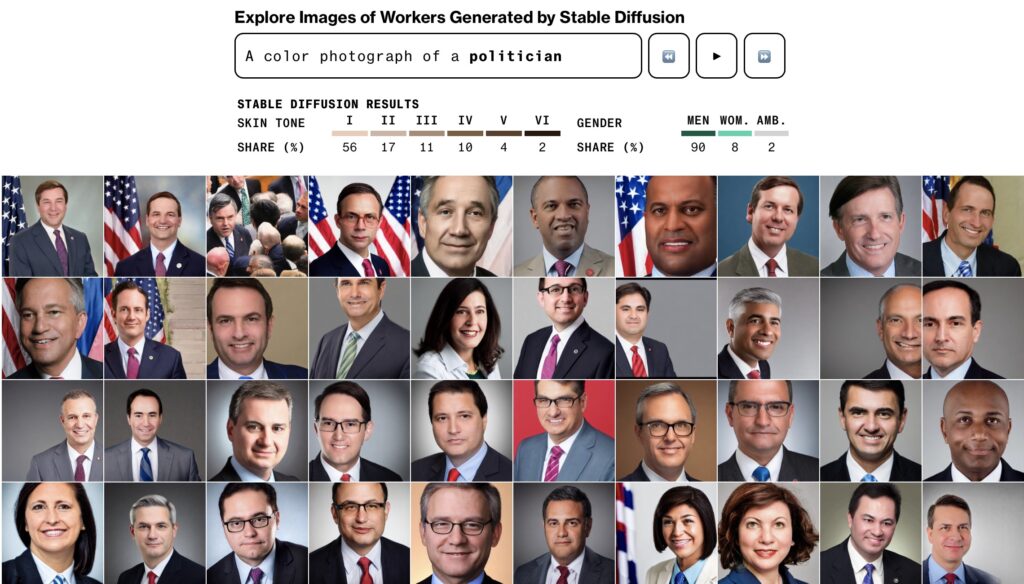

For example, prompt engineering often focuses on generating results using stable diffusion algorithms and software like Adobe Firefly. However, the datasets powering these algorithms are biased. If you type “color photograph of a politician,” you rarely get images of people of color, which reflects biases in the underlying databases. If designers aren’t critical of this, they risk perpetuating these societal biases.

Raising awareness of these biases isn’t enough—we need to expose these contradictions to the public. Instead of just generating images, we need events that foster dialogue and interaction. I’ve found speculative and critical design effective tools for promoting debate about technologies like AI.

Juliana Saito, a former digital design student at PUCPR, created a system that raises awareness of procrastination habits through AI. The system discourages users from mindlessly scrolling through social media but sometimes encourages them to return to work. This kind of affective interface was crucial to her project. Her project anticipated the role that systems now play in shaping behavior. It highlighted that systems can not only be useful but can also make us feel useless, depending on how they are designed.

In 2020, we ran a Theater Forum activity with USP São Paulo design students. They were concerned about how generative AI might affect their employability. In the speculative design theater, AI hired a designer to create work for a client. The AI couldn’t generate anything valuable, so it exploited cheap labor through a system like Amazon Mechanical Turk. Using semi-automated, prompt engineering tools, designers were paid very little for their work.

At some point in the play, the designer becomes alienated and tries to organize a strike, but the system cuts them off. The story continues from there. This speculative design theater aimed to show students that design, like any other profession, is political and economic. Designers need to understand these realities, or their work could be jeopardized.

My goal with generative AI is to foster critical consciousness—not just to stop what we don’t like, but to redirect the technology, much like in capoeira. We don’t need to abandon AI—we need to guide it toward a new direction. This idea of regeneration parallels environmental efforts like coral reef restoration. Marine biologists build structures to encourage coral growth, restoring damaged ecosystems. Over time, the reefs regenerate, sometimes becoming richer than before.

Similarly, we can regenerate AI by creating open, collaborative platforms. When Google Drive became popular, we noticed it replaced critical face-to-face interactions. In response, we developed Corais in 2011, a collaborative platform with a transparent, open structure. All projects on Corais had to be public and licensed under Creative Commons, encouraging further collaboration. Since then, the platform has hosted over 700 projects, fostering unexpected learning opportunities. I learned about solidarity economies and social currencies—ways to shield local communities from global capitalism—through projects on the platform. This network of collaborative projects embodies emergent performance—adaptive, collective behavior following simple rules with complex effects. We documented these insights in the book Coralizando, written by eight contributors across Brazil. The book is licensed under Creative Commons, allowing anyone to modify or expand upon it. Our goal was to encourage collaboration and solidarity in cultural production.

To theorize emergent performance further, I now see it as a shared object with multiple outcomes. These performances make contradictions in society more visible, creating opportunities for change. In short, designing for emergent performances is designing for change. Thank you very much for watching.

References

Van Amstel, Frederick M.C. (2015) Expansive design: designing with contradictions. Doctoral thesis, University of Twente. https://doi.org/10.3990/1.9789462331846

Van Amstel et al., (2014). Coralizando: um guia de colaboração para a economia criativa. Clube de Autores. https://clubedeautores.com.br/livro/coralizando-um-guia-de-colaboracao-para-a-economia-criativa

Other Tomorrows (2023). The Expanding Scope of Design. Report. https://www.othertomorrows.com/project/the-expanding-scope-of-design

Amstel, F. M.C. van; Zerjav, V; Hartmann, T; Dewulf, G.P.M.R; Voort, M.C. van der. 2016. Expensive or expansive? Learning the value of boundary crossing in design projects. Engineering Project Organization Journal, 6 (1), Pages 15-29. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/21573727.2015.1117974

Reynolds, C. W. (1987, August). Flocks, herds and schools: A distributed behavioral model. In Proceedings of the 14th annual conference on Computer graphics and interactive techniques (pp. 25-34).

Araújo, J. V. T.; Dembinski, C. (2022). SURU’BA: Sistema Utilitário Recombinante Utópico-Universal Baseado na Autonomia. TCC em Design. UTFPR. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/381880274_SURU’BA_Sistema_Utilitario_Recombinante_Utopico-Universal_Baseado_na_Autonomia

Ramesh, A., Dhariwal, P., Nichol, A., Chu, C., & Chen, M. (2022). Hierarchical text-conditional image generation with clip latents. arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.06125, 1(2), 3. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2204.06125