Abstract: What is the difference between knowledge and consciousness, and why does it matter for design? This lecture examines knowledge as a product of consciousness, emphasizing that while knowledge organizes what is already known, consciousness enables the creation of the new. Using examples like ChatGPT—an entity rich in knowledge but devoid of consciousness—it critiques traditional design methodologies that separate designers as “knowers” from users as “objects of design.” Tools like Lego Serious Play and The Blind Side are presented as ways to bridge this divide, fostering hybrid identities that blend user and designer perspectives. By advocating for self-managed design studios, it highlights how shared subjectivities can redefine design as a collaborative, socio-political act of liberation.

This lecture was recorded in the Spring 2025 Research and Practice MXD MFA course at the University of Florida.

Video

Audio

Full transcript

If you don’t know what knowledge management is, I’m not going to explain it precisely because I’m going to say it’s good that you don’t know what it is. It’s best not to know what it is because the kind of design research we do here—based on codesign and participatory design—is not exactly the most productive, nor does it lead to the best results, if you rely on knowledge management or, as soon I am going to state, knowledge of hetero-management. What works for us is knowledge self-management, which I try to explain here what I mean by that.

I will remind you about some things you’ve seen in past lectures and our discussions and workshops. We must ground this discussion in practice, not just philosophical or prescriptive logical speculation. When I talk about knowledge as a goal for design research—producing new design knowledge—I also remind you that knowledge comes from somewhere, and that is consciousness.

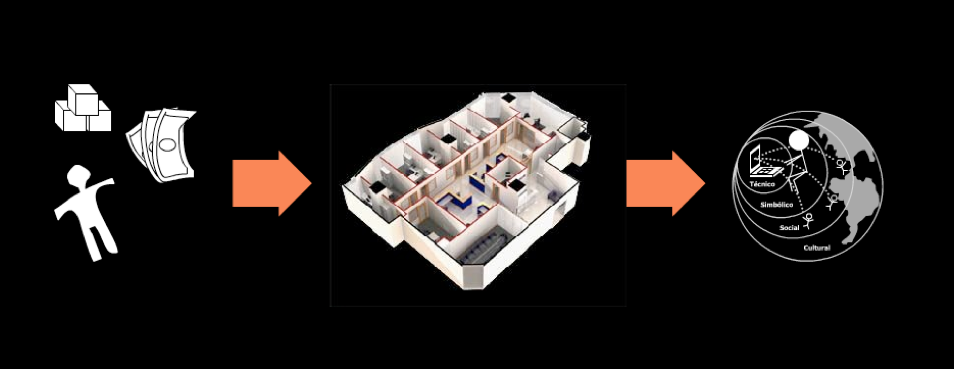

When we are doing design research, we are expanding the boundaries of what we consider to be design, designable things, and design partners. We go beyond exchanging money and objects (like you design an object, and you get your money). Some designers have this very restricted mindset of naïve consciousness, as Paulo Freire and Álvaro Vieira Pinto called it. But as soon as they start reading or talking to other experienced professionals, they will see that there is, at least in the workplace, a point where these relationships become complicated. You don’t just deliver an object. You have to discuss with many people what the requirements of that object are—the briefing. Once you have some initial visions of that object, you will need to collect feedback and make changes. Sometimes your project might even be canceled halfway through, and you don’t get paid. You might get angry at people, but it’s just part of the job, part of the workplace culture. Facing contradictions is inevitable.

As soon as you go a little deeper into questioning where these contradictions come from, you start to unfold capitalism, environmental degradation, and any other kinds of contradictions that pervade and shape the world we live in. Expanding consciousness is one fundamental aspect of design research. It’s often neglected because we still focus too much on products in design research, inheriting traditions from industrial design. But in the reality we live in today, shaped by post-industrialism, we need to focus a lot on process and be mindful. The concept that helps us bring this forth is consciousness, not just knowledge.

Make no mistake—knowledge does not come from knowledge. Here’s a book about sketchbooks. It’s almost like a meta book, right? If I read this book, it doesn’t mean I will get new knowledge. I have to work out what is in this book, relate it to other books, and do something with it. There is some mediation necessary to transform knowledge into new knowledge. So, if I want to write another book, I probably need to read many other books. I can’t just read one book and, from that one book, generate an entirely new book. That would probably be a copy of this book if I only read this book.

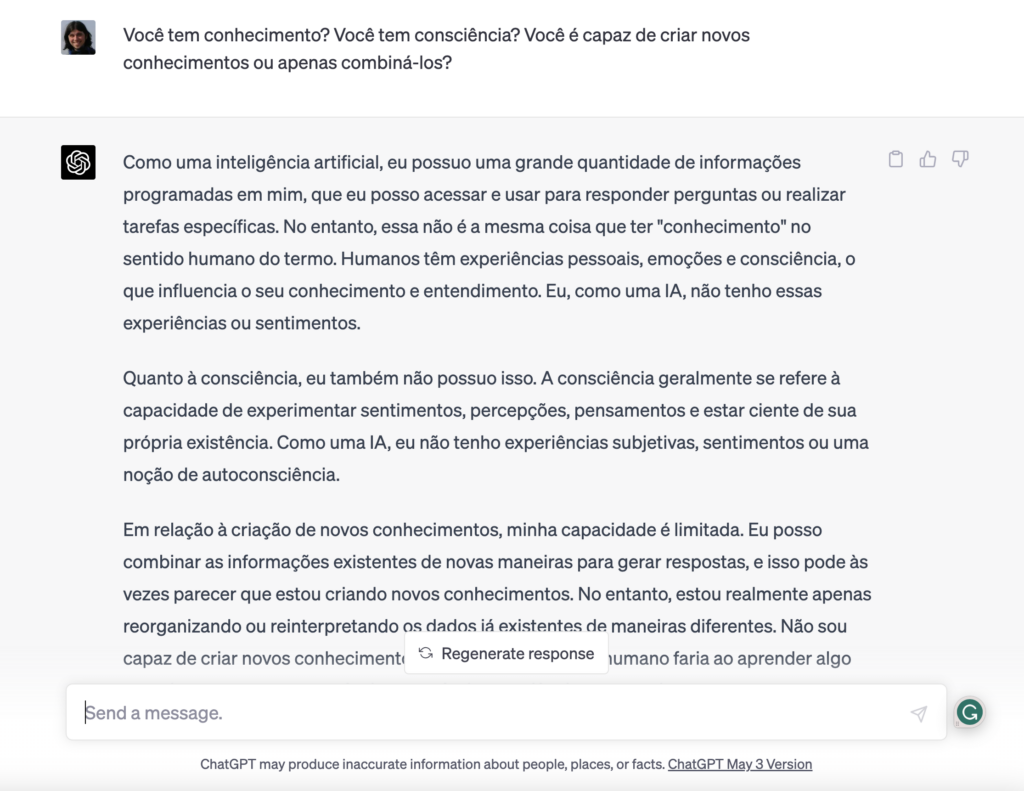

Knowledge does not come from knowledge. Knowledge comes from consciousness. However, there’s a difference in the agency of knowledge and consciousness. Knowledge doesn’t expand without consciousness. However, consciousness can expand without knowledge or with very little knowledge. Two examples here: ChatGPT represents knowledge without consciousness, and as such, it cannot create new knowledge. That’s the reason why ChatGPT cannot create new knowledge. It can combine, mix, or hybridize at most—but it’s not creation; it’s just combination and recombination.

One of my first questions when I started interacting with ChatGPT a few years ago was: “Do you have knowledge? Do you have consciousness? Can you create new consciousness or only combine?”) It provided a transparent account of its lack of consciousness. As for knowledge, well, ChatGPT sometimes says, “I only have information, not knowledge.” I do believe that information is also knowledge to a certain extent, but that’s a debate. Some people don’t believe it. In the past, I believed differently. I thought that information could exist in systems or in the world but not as knowledge. Knowledge could only exist in the heads of people. Then I started reading Hegel, and he changed my mind.

Because if we don’t consider space to have any knowledge in itself, why would we need space? I mean, we could meet online and have this entire three-year MFA program on our Miro boards, doing virtual conferencing. The reason why it’s so important to be in this studio is that this studio embodies materialized knowledge. It’s also materialized knowledge in a stage when it’s not so, let’s say, consolidated.

A few weeks ago, we had this economic trading game in which we had to play with basic trading strategies without knowing much about their consequences in the overall financial system. That was fine because we could create new knowledge even with little knowledge. We had a surprising discussion about how our previous experiences with real-world economic systems unconsciously shaped our behaviors and strategies while playing this game.

That’s an incredible aspect of being human. We make a difference not through knowledge—although that’s important—but mainly through consciousness.

There are many theories about what knowledge is. I can’t go into much detail here, but I agree with the basic premises of the connectionist theory of knowledge. It’s often visually represented using a meme: data is the opposite of knowledge, or basically, knowledge is the richest form of data, connected and meaningful. That’s what knowledge is—enriched information, which is, in turn, enriched data.

That’s one way to see it. It’s very influential in the information design field, and many information designers, with their graphic diagrams like this one, try to connect the dots. It’s not that simple, but I won’t discuss this.

What I want to draw attention to, and help you see, is the difference between knowledge and consciousness—not between knowledge and information—because here, the difference is much, much, much, much bigger. We are talking about something completely different when we say “consciousness,” although in simple language, in common sense, people might use those words as synonyms. Even in English, there is a lack of nuanced vocabulary for talking about consciousness, and people might say, “I know,” when they mean, “I am conscious about it.” They don’t use the nuance of the language, so this word is not very popular, but it exists, and it helps. See how it changes with this example of anti-userist design research.

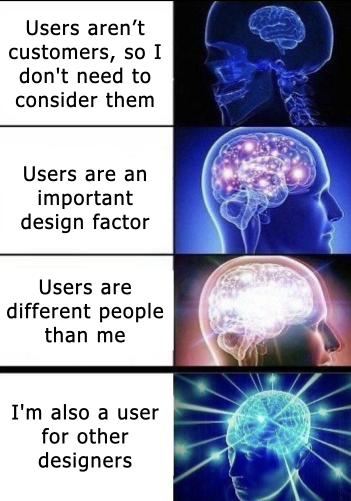

As much as I used ChatGPT as an example of knowledge, here I am using anti-userist design research as a kind of consciousness. Here’s the progression: In the most alienated state, you think users are customers. You don’t need to consider your product or service in your project if they don’t purchase your product or service. They are not hiring you. Remember the first stage of design consciousness I showed before: I design objects, I get my money back. If the person is not paying my paycheck, I should not attend to that person.

However, if you expand your consciousness a little, you will see that users are an important design factor—a factor of your design—not a person with personal history, contradictions, and challenges. If you go a bit deeper or wider, you see that users are different people than you, and you cannot rely on your knowledge about yourself to understand what’s going on with the user.

The breakthrough in your consciousness is when you cross the chasm between framing users as users and seeing yourself as a user. Seeing that users are people like you—that you are also in the same condition in relation to other people—is key. Consider the designers of design tools, for example. If you are not designing your Photoshop, so you are a Photoshop user. Although you think that when you sit in front of Photoshop you’re acting like a designer, that’s not true. You’re mostly acting as a user, and your designs are going to be narrowed down by the Photoshop designer. You won’t be able to design everything you want unless you design your own Photoshop or something similar.

That’s precisely what we do here in this program. We design a lot of design tools. We do metadesign. They’re not as technologically advanced yet but have more critical consciousness. They enable critical consciousness so you can develop new knowledge.

Consciousness produces new knowledge from experiencing the world. When the knowledge product is known beforehand, when it has already been experienced, consciousness becomes less productive because consciousness exists to produce knowledge in the first place. But if you are not creating new knowledge, consciousness becomes less active, and then, at some point, you become subconscious. You become less conscious and automated because you’re not producing anything new. You’re just acting like a robot. Consciousness becomes less awake.

That’s why sketches, scroll keys, and design models are deliberately vague. They mediate the back-and-forth movement between what is known and unknown and aesthetically stimulate our consciousness to produce new knowledge. That’s a characteristic of design thinking. Having all of this mass in our studio also means we welcome the unknown and want to connect the unknown with the known to develop new knowledge.

If you’re feeling confused—and I’ve said this sentence many times—if you come to me and say, “I’m confused, Fred,” I would say, “Great!” (laughs) But here’s the reason why: because there’s a good chance you are exploring something unknown. Conversely, if you are too sure about something, chances are you’re not producing, just reproducing knowledge. So, if you are overly confident, it’s also not a good sign. That’s the thing you should not strive for—to become so sure that you know everything about design. Because then you probably won’t understand anything about design. You will know only how to give form to a pre-defined ideology you don’t know you know.

Design research methods typically stimulate you to become mindful and conscious about what you are doing so you remain open to the world. You must have an open conscience, an open mind, to things that will pop up in the future that you cannot anticipate. That was the case for the design of the Sydney Opera House. The sketches I showed before were part of the design process that led to this marvelous, incredible design—this absolute piece of knowledge that stands in that city. The building itself embodies the accumulated design knowledge of generations of architects, engineers, and graphic designers. But before knowledge gets closed into things, it lives in this open state throughout the design process.

The crucial knowledge production challenge is understanding an experience you’ve never had and will probably never have—the experience of the other. Remember, I said that consciousness produces knowledge from experience. But can you produce knowledge from an experience you haven’t had? Of course, you can. However, it’s risky. You may end up making up an experience of someone else. That’s where ideology starts to play a role.

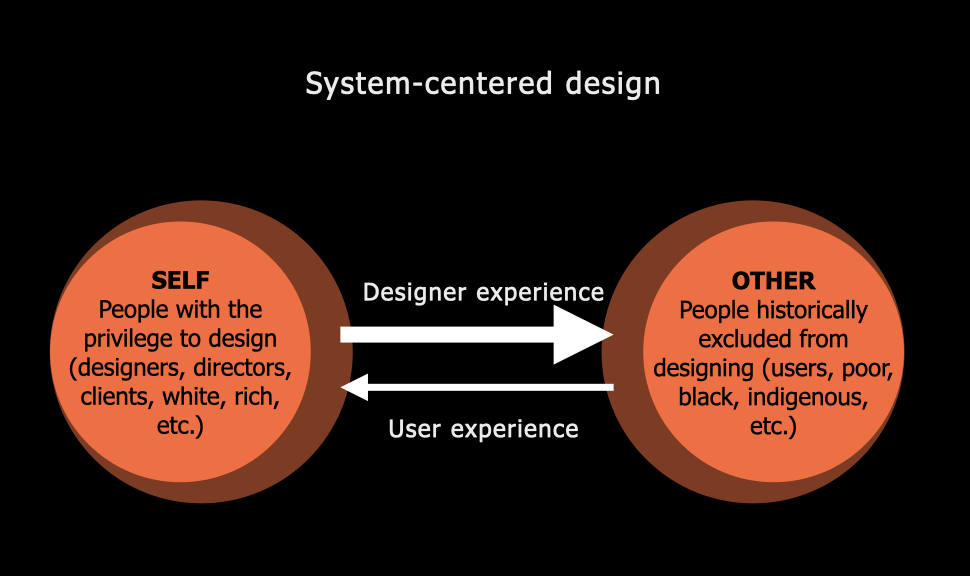

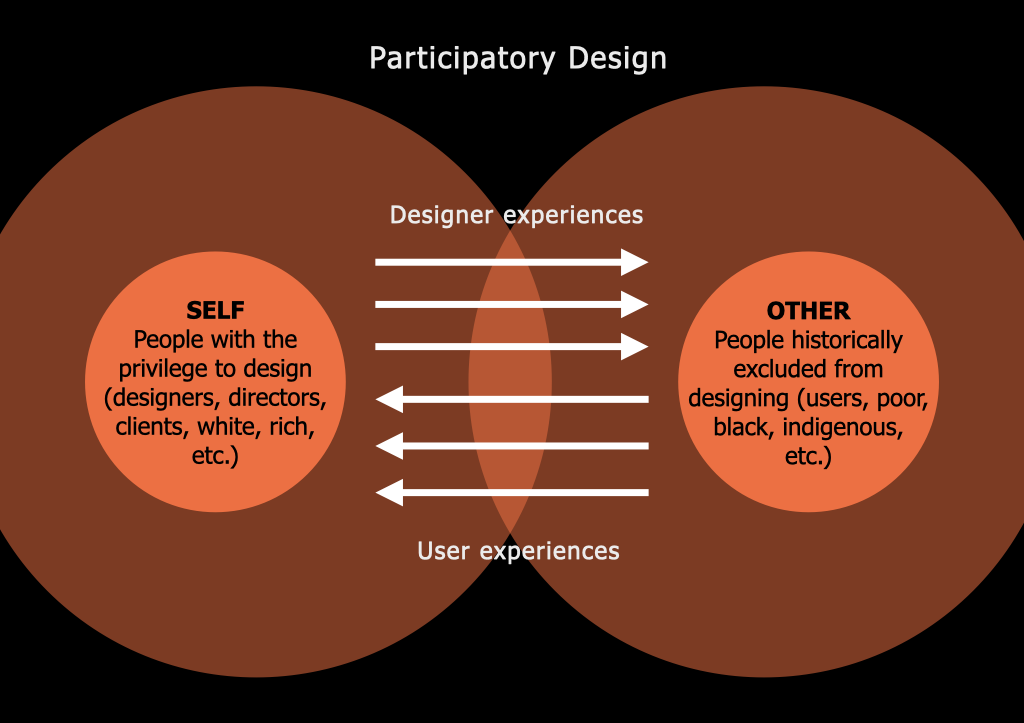

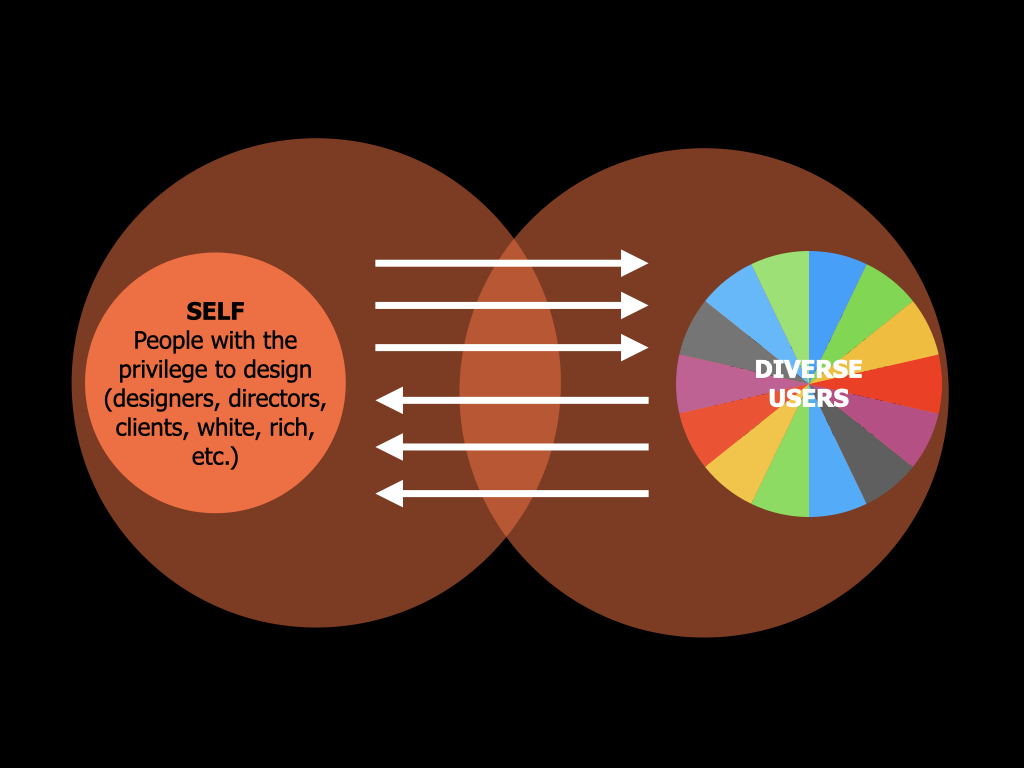

Here are two methodologies of design that are more than just methodologies—they are also ideologies of design because they are based on very naturalized, accepted ways of grouping people. In system-centered design, there is a group of people who believe themselves to be the experts, who think they know how to design a system better than anyone. They have experience; they have designer experiences. And their design is forced on another group of people who don’t have that expertise: laypeople. These people are historically excluded from design. They don’t participate much—at most, they display or exhibit their user experience in a public space, or they agree to share their data so that the designers can incorporate some user experience while promoting their own view. Their interpretation is always predominant in system-centered design. The designer’s experience predominates over the user’s experience. That’s the ideological aspect of this methodology, which is typically not discussed much.

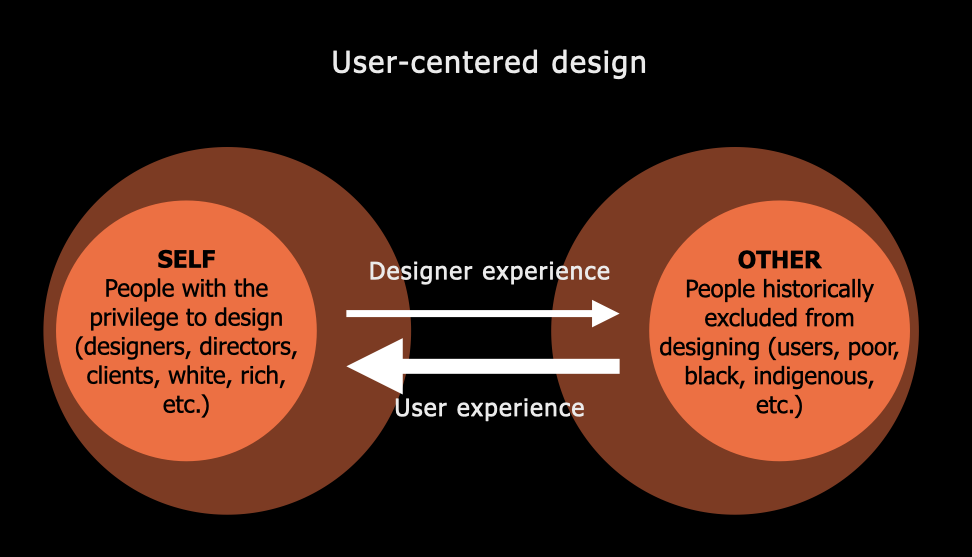

The second ideology/methodology, called user-centered design, is almost the same. The only difference is that the user experience is prioritized over the designer experience. So there’s more space for the user to voice their problems, their challenges when interacting, their motivations, behaviors, body qualities, and so on—relevant things so designers can adapt the system, shape the system, to better fit user needs, so to speak. However, the ones who ultimately make the decisions are not the users themselves—they are the designers.

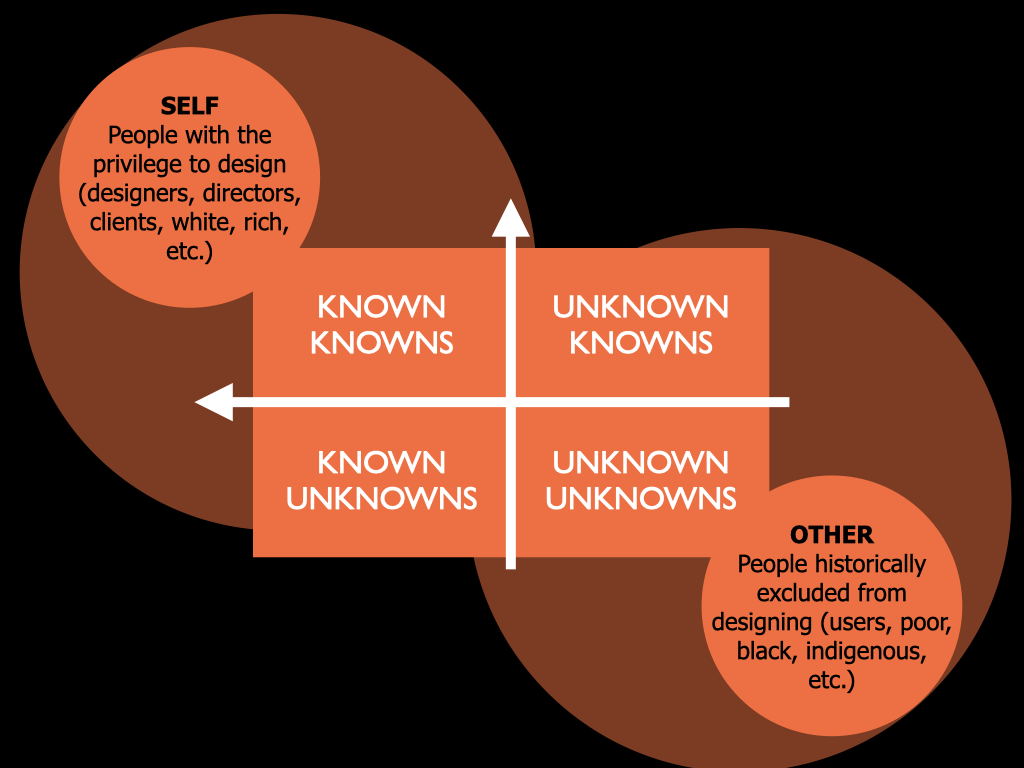

That’s why I’m using this more general distinction here between two social groups: the “self,” who is acting, who is the subject of the activity or the subject of design—the subject supposed to design—and the “other,” who is supposed to be designed, who is supposed to be the object of design. User-centered design is, technically, a methodology that rests on the ideology of userism that justifies such a divide between social groups.

For the production of knowledge, this implies that design knowledge is mostly about the other, not knowledge of the other. The “other” embodies the unknown as an exotic stranger that may be known by design but never by itself. So, the “other” doesn’t have knowledge—or at least doesn’t have any design knowledge. The other is not a source of knowledge. That’s the basic premise of the two ideologies/methodologies I just showed before. Nevertheless, this is not something exclusive to design. It’s also part of a modern, colonial, and Western way of dealing with knowledge—separating two social groups and recognizing that some groups produce knowledge, while other groups don’t produce any knowledge.

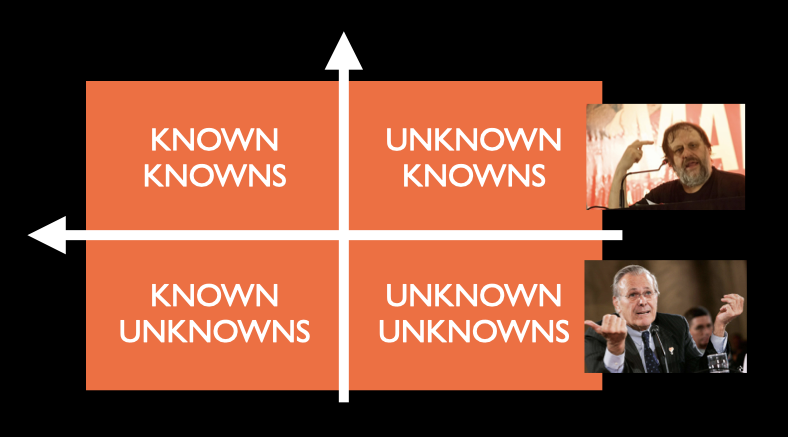

Here’s an example. I already mentioned this before in a past lecture on self-management. Donald Rumsfeld, as the US Secretary of Defense, justified invading Iraq around 2002–2003 by saying that Iraq was an “unknown unknown.” There were possible weapons of mass destruction that the US hadn’t even heard about, so that’s why, according to him, they should invade Iraq. But that was a fallacy, because how can you justify doing something so horrible as waging a war with so many unknowns? It can go really bad, and it did go really bad, much worse than the US anticipated at that time, without having any real evidence. That’s what he was essentially saying: we should conquer something just because we don’t know that thing.

It’s very paranoid, and a lot of people criticized that discourse and speech. Unfortunately, we still have contemporary politicians who may be even more paranoid, and people are just accepting this as normal. Luckily, we do have critical thinkers like Slavoj Žižek, who observed that specific speech critically when Donald Rumsfeld talked about the “unknown unknowns” and, in some way, bamboozled the public. A lot of people thought it was a clever way of avoiding the truth, which was that they were invading Iraq to maintain geopolitical hegemony over the Middle East. That was the truth—or, to put it more bluntly, to keep the hold of the American empire over that region.

Nowadays, I feel comfortable saying that after Bloomberg, Economist, and right-wing media are using this term openly. There’s no problem in saying “American” or “US imperialism” any longer. Even the president himself is almost saying it. Unfortunately, when Rumsfeld bamboozled the media, if someone raised such a concern, it would sound very offensive because America was supposed to be a democratic country at that time. That was the image America wanted to show the world, which is no longer the case.

As Slavoj Žižek wrote in 2006, there is a third quadrant that Rumsfeld didn’t talk about: the “unknown knowns.” An example is ideology, a topic Žižek humorously explores in his movie The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology (2012). The critical aspect is that Žižek helped us create an opposition here—the dialectics between knowledge and consciousness.

If you look at this map here, which you’ll see in the literature on knowledge management, they won’t tell you this. This is something that only a Hegelian like Žižek can see—the difference between knowledge and consciousness. The first “known” here does not refer to knowledge; it’s about consciousness. And the second one is about knowledge. So, “known knowns” refers to the consciousness of that knowledge.

You can also define consciousness in simple terms. What is consciousness? It’s a hard question to answer. But even harder is: what is knowledge, right? But you can say that consciousness is “knowledge of knowledge.” That makes sense, right? It’s a simple way of framing it. The simple definition helps you because you can build a graph like this with four quadrants, and you can operate it and see what it means for something to move from one place to another.

You can also design things based on it. Any knowledge starts as less conscious and less knowledge, right? And then it grows into something sure—assumptions that you are sure about, the “known knowns.” But along the way, it can travel and go back. That’s the advantage of using this kind of visualization.

Okay, so Žižek’s philosophical analysis concluded that Rumsfeld’s discourse wasn’t about knowledge management but ultimately about managing the other. In a word, hetero-management. So here’s how it connects to my past presentations about self-management. Indeed, this kind of knowledge management matches hetero-management. It dovetails and is a cornerstone because the “other” is supposed to be known.

You need to protect yourself from the threats of the unknowns, so you have to transform the unknowns into knowns and the knowns into “known knowns.” But you don’t want to accept that the “other” has its knowledge. The “other” is an object because it is a historically excluded person, an oppressed person. This ideology behind knowledge management—or knowledge hetero-management—uncritically is reproduced in design literature.

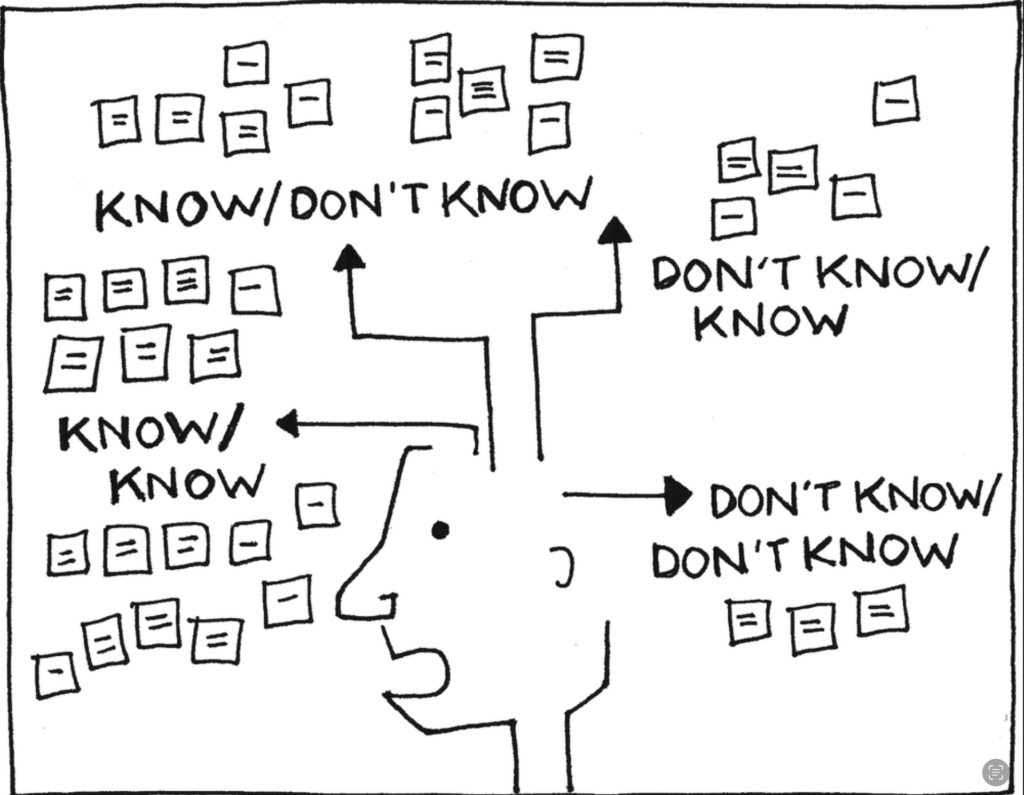

For example, The Blind Side game, which we draw on a lot to implement this matrix in our studio, comes from the Gamestorming book written by Dave Gray and colleagues. It does not acknowledge this ideology. Instead, it reproduces it, saying, “Okay, the Rumsfeld Matrix is about things that we know we don’t know.” And there’s even a figure—a stereotypical male figure—talking about knowledge in the head. So, it obscures this rich discussion and even the foolishness of Rumsfeld’s speech. That’s why I need to provide this critical contextualization so you don’t reproduce this mindlessly.

Think about what role that tool could play in a situation where you are trying to overcome hetero-management. In hetero-management, designers and users are separated by interfaces. You design an interface to control users, following a similar hierarchical lack of power as between managers and workers. Participatory design emerged to alleviate the contradictions of hetero-management in Scandinavia, which was not a communist or socialist region in the 1970s but suffered a lot of pressure from socialist countries. Participatory design was influenced, in a way, by socialism, and some of its elements were incorporated into its majority capitalist framework, resulting in what is known as the Scandinavian welfare state—one of the most enduring examples of what we now call social democracy, or something like that.

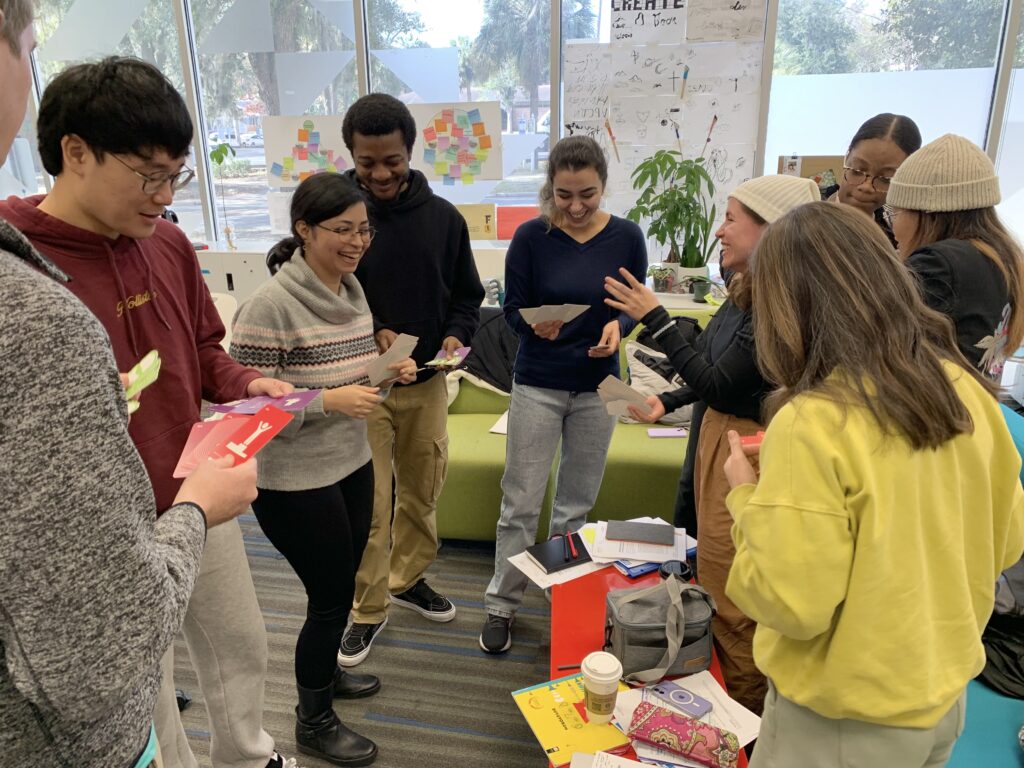

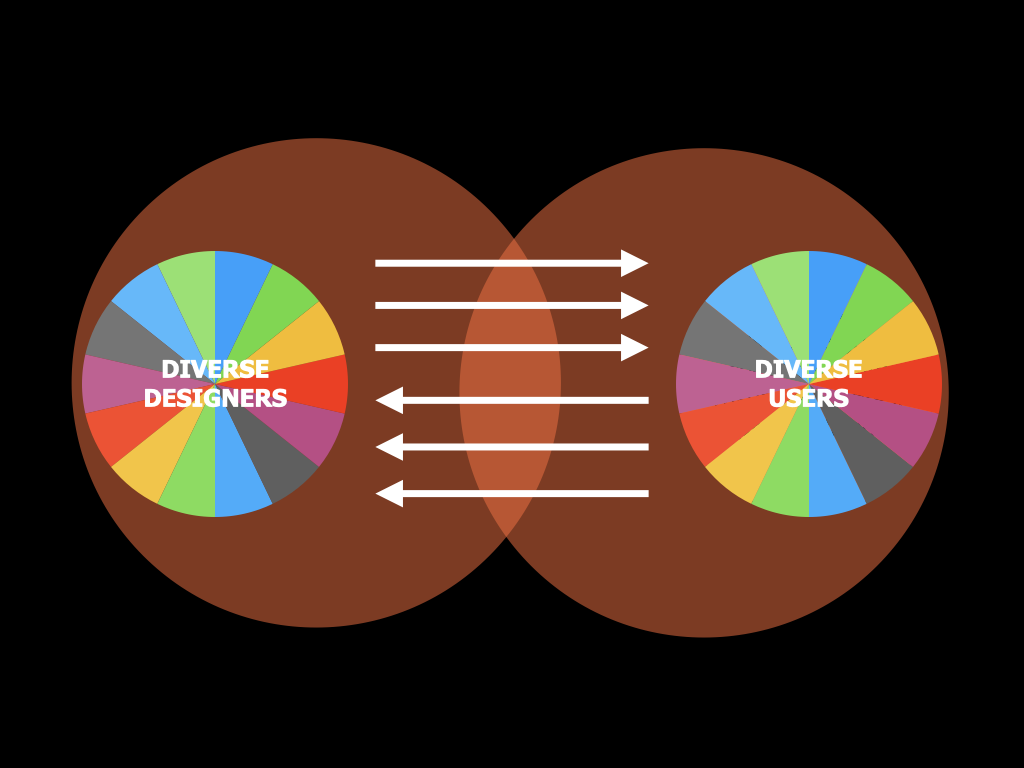

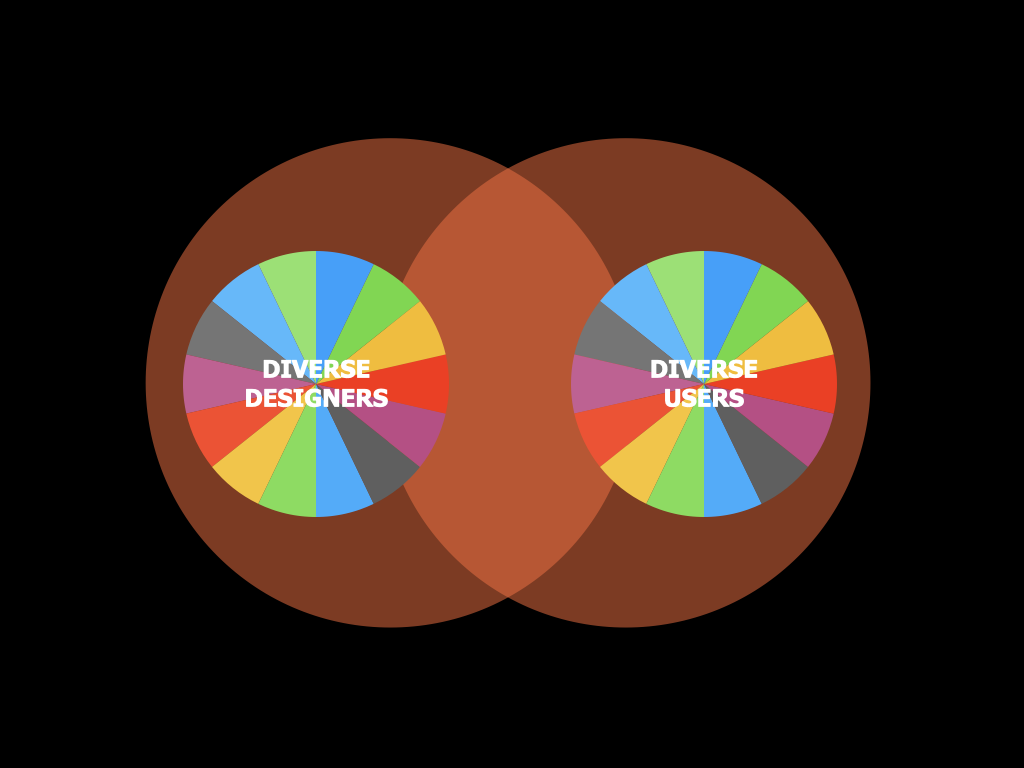

To alleviate that contradiction, participatory design diversifies the knowledge produced at the interface. Instead of having one designer experience and one user experience, you have multiple user experiences and multiple designer experiences. They exchange experiences through participatory design, and as a result, consciousness expands on both sides. One of the significant outcomes of participatory design is mutual learning. Designers learn from users, and users learn from designers. That’s cool.

However, that’s not all that we can do here. We can do more than that. How does participatory design do this? To diversify knowledge, participatory design represents shared objects—also known as boundary objects—at the designer-user interface. If you look closely at the overlap between these two different kinds of consciousness, you will see things emerging that populate this studio.

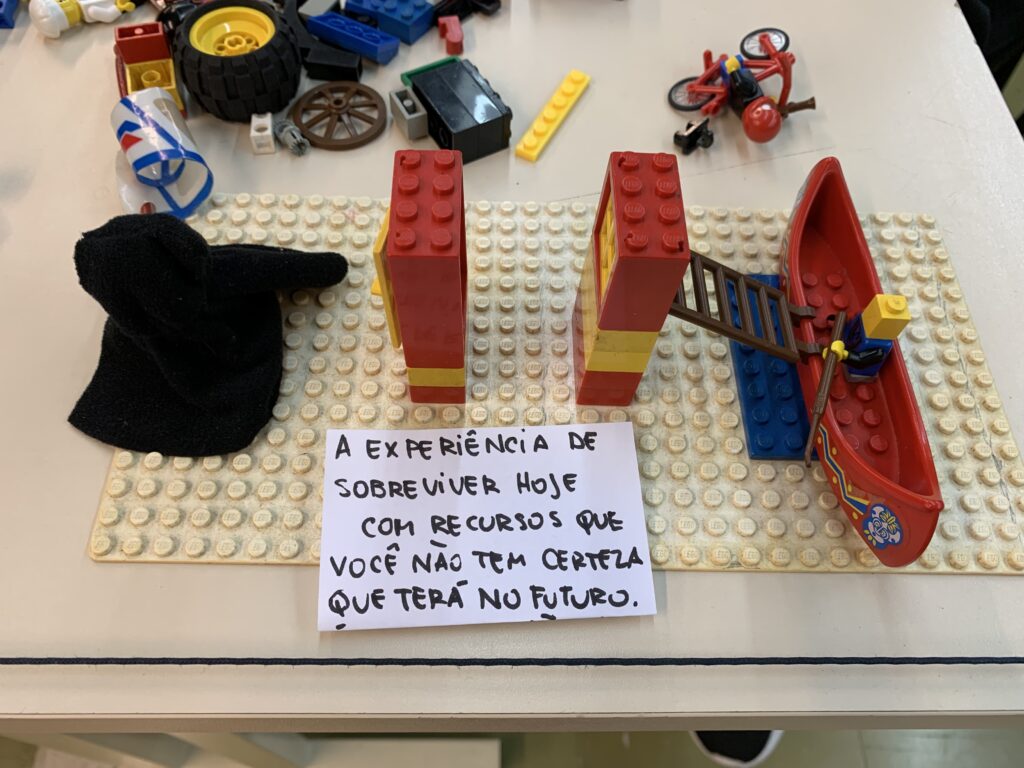

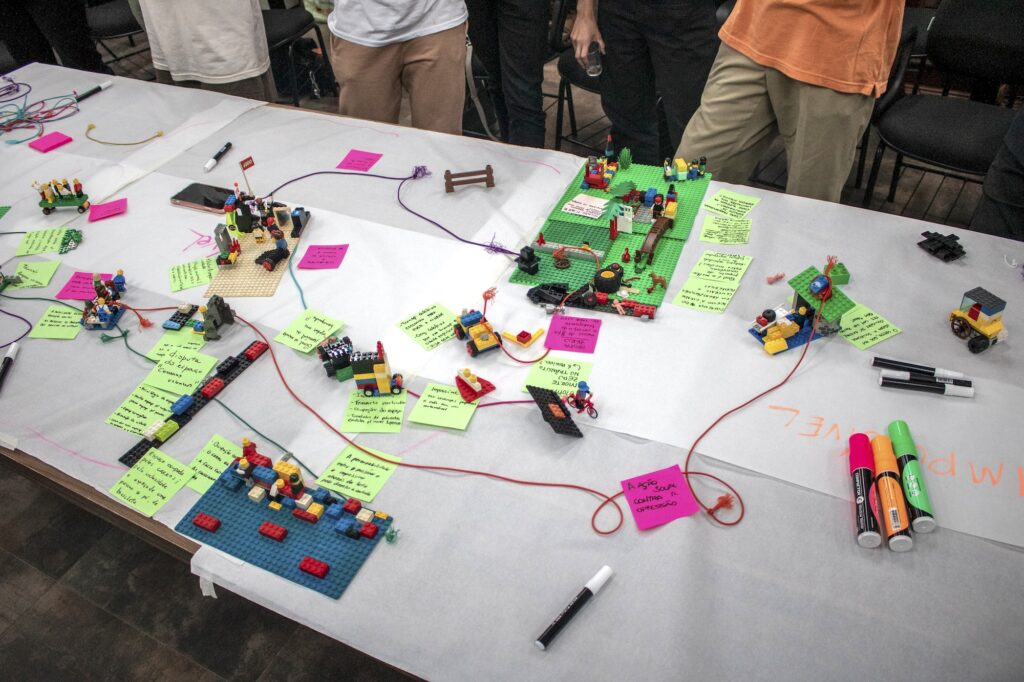

Lego Serious Play, one of my favorite materials, is something I learned to use at that interface from my PhD supervisor, Masha van der Voort, and one of my PhD colleagues who also worked with her, Julia Garde. I also co-wrote a paper with Julia Garde too on service design games. Back in those days, Julia was very interested in using Lego Serious Play as a codesign material without transforming it so much that it would lose its original features, like the metaphorical model. Most of the time, when designers build objects, they build them literally. They don’t use metaphor much. For instance, if they’re going to design a cup, they will draw a cup. They won’t think about, “Okay, if I’m going to design a cup, let’s first think about a metaphor for drinking,” and then, for example, draw a mountain where the water comes to think about other ways of delivering water to a thirsty user. The “mountain” is what we do here. We use Lego Serious Play, and we do that because we want to explore concepts more deeply. I learned all of this from them, and I started to apply it in my own classes and in my own participatory design practice.

One thing that I learned to be very useful is to ask people to represent their research objects. “What would you like to know more about?” This enables people to express their research object, even if they know little about it. Further, if you ask them to write down what they already know about this object and what they don’t, the shared object—represented as a Lego Serious Play metaphorical model—helps people keep their attention focused on their knowledge. It’s almost like a reflection, like a mirror. When you look at a Lego Serious Play model, it’s like looking into a mirror.

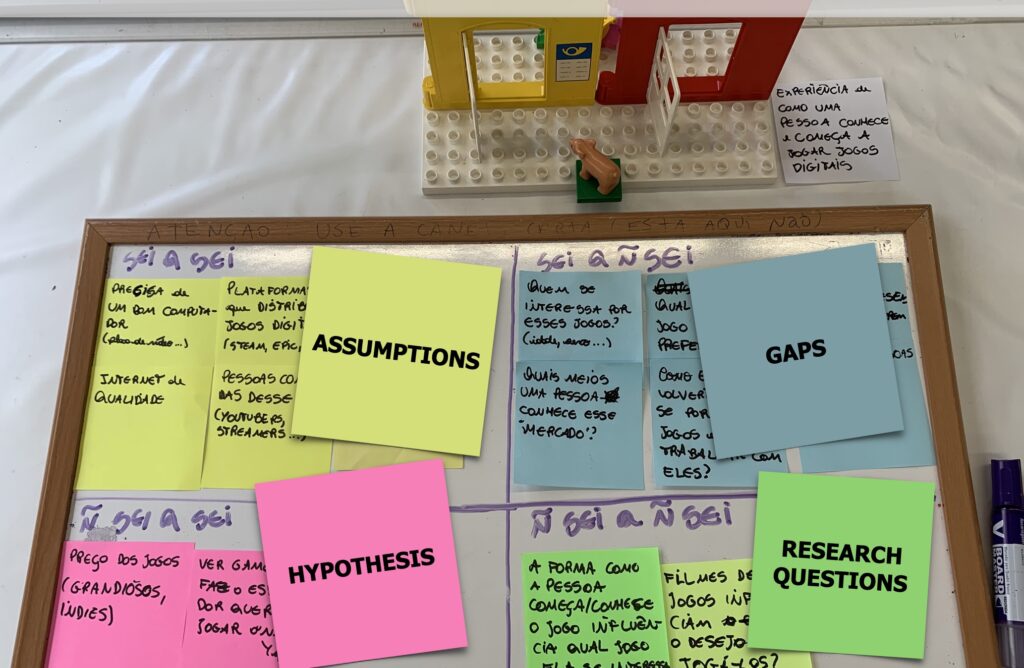

After they write down everything they know or don’t know, they can map it into a Blind Side game—this Gamestorming activity: “I don’t know that I know,” “I know that I know,” “I know that I don’t know,” and so on. They can use this visual to plan and become more aware of their research project. You can use this too. I highly recommend it, especially for second-year MFA students and researchers. Create your own research object using LEGO Serious Play and later create your own Rumsfeld/Žižek matrix. Ask yourself: What do I already know about it? What do I want to know? These are the fundamental questions.

You’ll see that the quadrants of the matrix closely match a research project. You’ll essentially be sketching your research project—a research project proposal that you need to deliver by the end of this semester. In the quadrant where we ask about things that you know that you know, these are assumptions—also called premises. Things that you know that you don’t know are gaps. Things that you have an answer for but are not so sure about are hypotheses. And things that you don’t know that you don’t know? Use research questions to get there. If you write a research question and already know its possible answer, it’s not a research question—it’s a hypothesis, and you’re using the wrong format. Remember this, okay? A lot of people make this mistake.

To answer the earlier question: I recommend you do this on your own first and as soon as possible share it with someone else to get feedback on your knowledge and your production process. Sharing your model, talking about it, and sharing what you know with another person enriches your consciousness. It also creates confrontation, so you may rethink the way you look at your research object. But the best way, even better than that, is to do this as part of a big group where everyone is modeling a shared object. This can be done using Lego Serious Play in the landscape phase. We rarely get to this phase here because it takes time. Before you build individual models, you have to connect them, and then you can create the landscape model.

At this point, self-management goes beyond participatory design because it’s not just about producing shared objects—”we have”. It’s about producing shared subjects—”we are.” That’s more fundamental and difficult. Here at MXD Studio, I think this is our contribution to the history of participatory design. What we are trying to do here is not so much to produce diverse shared objects but, first and foremost, to produce diverse shared subjects. I’ve also used the term “collective design body” in other papers to discuss this shared subject.

Here’s a visual representation of this. Participatory design, even in user-centered design, already considers and welcomes diverse users—listening to others and seeing them as people, not just objects. But what we do at MXD Studio is so unique because we emphasize that diversity should also exist on the designer’s side.

That’s why we co-design so much—because we are diverse people in this studio, and that’s one of our strengths. However, I’m proposing that our next steps should not lose the opportunity to embrace the fact that we are also diverse users. Instead of the traditional divide between designers and users, I envision blending those social groups.

In my tenure as Director of Graduate Studies for this program, I am introducing the self-managed studio approach to not only diversify knowledge but also the knowers in design research. That means producing knowledge about the self, for the self, and by the self. In fewer words: knowing who we really are. That’s what knowledge self-management means. It has nothing to do with improving profitability or efficiency, as traditional knowledge management often focuses on. Knowledge self-management is about knowing who we really are. But then, who are we, really, if we are so different? That’s an interesting question.

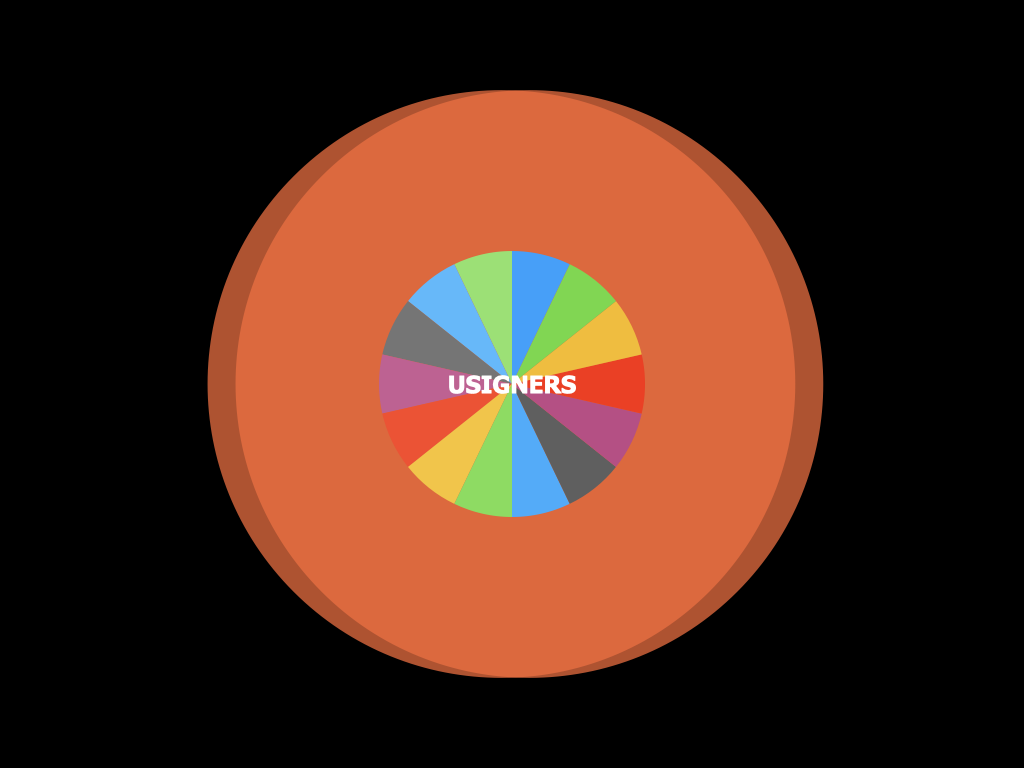

We have so many different nationalities, genders, races, and mental and physical conditions here. Here’s one idea: if diverse users and diverse designers collaborate more and more, producing self-knowledge in the process, you might eventually realize that you’re not that different. So I’m proposing that we see ourselves as a hybrid between a designer and a user—a usigner.

I’m drawing this term from Augusto Boal’s Theater of the Oppressed. He created the term “spect-actor” to define the role of people in his theater. I think it’s similar to what we are doing here with this hybrid concept of usigner. In a self-managed design studio, the shared subject we produce, this collective design body, is the usigner. It’s a transitional identity in the process of liberation from userism, also known as user oppression.

If you think user oppression only affects other people, you’re thinking in a very userist way. Because as a designer, you’re also a user of design tools and you’re also treated as a user. If you’re a designer from the Global South, most of the time, you’ll be treated as a user. You come all the way from your home country to study design at the US, you go through so many immigration hassles, just to become addicted to US design tools like Adobe tools. Then, when you go back to your home country and try to use those tools, and you can’t afford them—or they’re not even allowed in your country. Then you’re forced to become a criminal by pirating the software. As a designer, you’re trapped because you don’t know any other design tools like free software alter/natives.

That’s not the case in this studio, right? We already have enough people with critical consciousness here to tell you, “Don’t do that.” And we are in the U.S., which still has some democracy. Adobe hasn’t lobbied enough to force me to tell you otherwise. Hence we can still have a debate about free software and design design tools. Let’s keep using the freedom we have here otherwise we might lose it.

References

Norman, D. A., & Draper, S. W. (1986). User centered system design; new perspectives on human-computer interaction. L. Erlbaum Associates Inc..

Gray, D. Brown, S. and Macanufo, J. (2011). Gamestorming. O’Reilly Media.

Rumsfeld, D. (2011). Known and Unknown: A Memoir. Sentinel.

Žižek, S. (2006). Philosophy, the “unknown knowns,” and the public use of reason. Topoi, 25, 137-142.

Garde, J., and van der Voort, M. (2016) Could LEGO® Serious Play® be a useful technique for product co – design?, in Lloyd, P. and Bohemia, E. (eds.), Future Focused Thinking – DRS International Conference 2016, 27 – 30 June, Brighton, United Kingdom. https://doi.org/10.21606/drs.2016.24

Gonzatto, R.F. and Van Amstel, F.M.C. (2022), “User oppression in human-computer interaction: a dialectical-existential perspective”, Aslib Journal of Information Management, Vol. 74 No. 5, pp. 758-781. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-08-2021-0233