Capitalist service design is grounded on a theater metaphor that guides service designers to make work invisible, away from customer scrutiny and public accountability. In this way, service design contributes to hiding the extreme work exploitation that digital service workers undergo, generating a situation where workers can only reclaim their visibility through striking. If service design wants to contribute to making work visible and recognized, it needs another theater metaphor. This talk presents Theater of the Oppressed as an alternative metaphor and methodology for a critical Service Design practice.

Guest lecture in the Codesign in Services course taught by Dr. Fernando Secomandi, TUDelft.

Video

Slides

Audio

Full transcript

The purpose of this provocation is to challenge some deeply ingrained concepts in this field. Believing in my formulation could lead to a total reconfiguration of the field, which is necessary because service design is falling behind other fields in acknowledging its past association with oppressive structures.

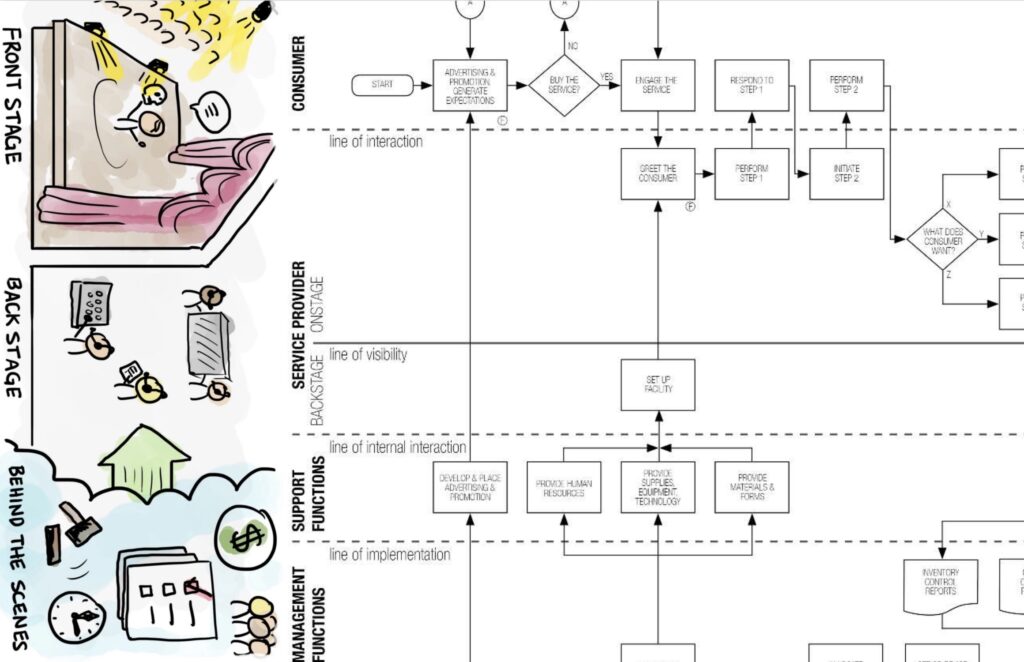

Let’s begin by denouncing that association. Service design, as many of you likely know, evolved from service marketing and interdisciplinary collaborations with industrial design, graphic design, and interaction design. Yet, service marketing still significantly influences service design today. An example of this influence is the division between the front stage and backstage, a concept now commonplace in service design that traces back to service marketing. This concept was initially introduced by Grove and Fiske in the 1980s and was thoroughly systematized in the 1990s. On one side, you can see a picture from their papers showing this division of front stage and backstage. On the other side, there’s a more familiar, derived diagram known as the Service Blueprint. This diagram is the predecessor of today’s Service Blueprint, initially created by Schoestack and later refined by other service marketers and designers.

This theater metaphor seeks to distinguish between the service’s visible aspects and its invisible parts. The visible part is referred to as the front stage, visible to the customer or client. Service providers and workers are aware of both the visible and invisible parts of the service, but they are encouraged to remain as much as possible in the backstage, the invisible area. On one side, you see a drawing, a diagram commonly featured in service design literature, blogs, and YouTube videos. On the other side, you see the practical application of this concept in the modern, contemporary service design blueprint. This blueprint includes a line of visibility, dividing what should be visible from the customer’s perspective and what should remain unseen.

A prime illustration of the benefits of concealing backstage activities is Disneyland, as extensively discussed in the book and article on Experience Economy. Although not exclusively about service design, this classic text in service design literature delves deeply into experience design and the broader experience economy. It articulately explains why work in service should be conceptualized as theater, emphasizing customers’ desires for delightful and memorable experiences without disruptions in their service flow. This notion of prioritizing experience is seldom questioned, as it’s seen as a positive aspect within the capitalist economy.

Following this theater metaphor, new methods and techniques, like experience prototyping and bodystorming, have been developed. These were notably popularized by Marion Buchenau and Jane Fulton Suri, who were design researchers at IDEO at the time. Such methods are widely recognized for allowing participants to deeply understand service experiences, such as the discomforts of being cramped in an airplane, from a more embodied perspective than could be achieved through mere drawings or diagrams.

Inviting customers, clients, and stakeholders to partake in these activities fosters a co-design approach. TU Delft researchers, including Peter Jan Stappers and occasionally Elizabeth Sanders, have significantly contributed to structuring this approach. However, co-design at TU Delft and similar institutions tends to focus predominantly on the front stage, leaving the backstage to be handled by other professionals. This practice perpetuates a theatrical and, arguably, capitalist assumption that work should remain unseen and interfaces transparent, ensuring nothing interferes with the customer’s fulfillment of their desires.

The question arises, why is co-design infrequently applied to the backstage? The reason lies in service design’s adherence to a theatrical and, arguably, a capitalist principle that work should remain unseen and interfaces transparent. This principle aims to ensure nothing obstructs the customer’s pursuit of their desires, allowing them to achieve their goals without noticing the efforts behind their fulfillment. However, this approach has significant drawbacks: invisible work can be easily segmented, managed, optimized, and exploited. Such practices distance the work from customer awareness and accountability.

This dynamic leads to a societal trend where service design masks labor under digital or physical veils, removing it from public discourse. Consequently, this invisibility often results in abuse, oppression, and undercompensation of workers. A visible manifestation of workers striving to make their labor visible is striking. Strikes by digital service workers, such as delivery couriers or Uber drivers, may seem antiquated but represent one of the few strategies to highlight their existence, oppression, and the exploitative systems under which they labor, particularly given the lack of adequate compensation and social security.

In this context, service designers face the challenge of how to render work visible again, encouraging scrutiny and sparking discussions on social justice. This necessitates exploring beyond the conventional theater metaphor to find a new paradigm that better represents and respects the visibility of all work within service design.

In recent years, my research has centered around Theatre of the Oppressed, a concept introduced by the Brazilian dramaturge Augusto Boal. Boal has authored numerous books on this topic and has traveled extensively to promote these practices. For Boal, theatre is fundamentally about work, not merely an art form for its own sake. He views it as a means to transform reality by presenting it in a new light, prompting us to act differently in the real world after experiencing it through theatre.

Traditionally, the theatre of the oppressors, or the dominant classes, has used performance to project their ideologies, incorporating their ideas, gestures, and rituals. This concept of theatre, which also extends to cinema and other media, essentially serves to maintain their control over cultural narratives. Boal’s objective is to democratize access to these means of production, allowing the oppressed to utilize theatre to voice their public statements. He developed methodologies enabling anyone to use theatre for public expression.

Comparing Boal’s Theatre of the Oppressed with the current capitalist metaphor in service design reveals stark differences in how work is treated. While traditional service design hides the work (backstage) to make the user’s experience (front stage) seem effortlessly magical, Theatre of the Oppressed places work at the very center of the stage, now referred to as the aesthetic space. This space welcomes everyone, transforming audience members into spect-actors who can step into the play, replacing actors to test their ideas in a theatrical setting, thereby assessing their applicability in real life. This approach fundamentally shifts the visibility and perception of work within the theatrical context.

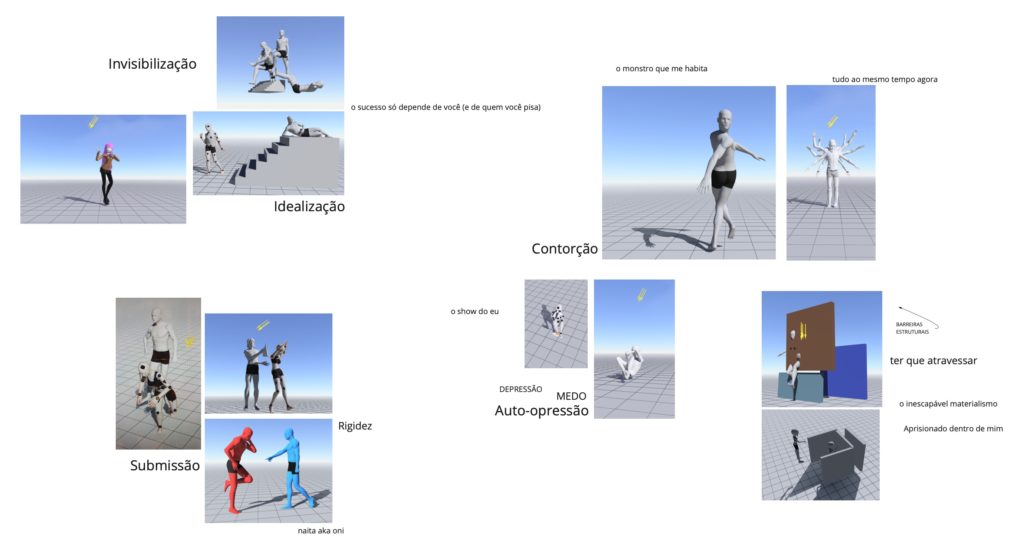

This process is both facilitated and at times complicated by jokers. Jokers are versatile participants in Theatre of the Oppressed, capable of assuming any role within a production. The ultimate goal is for everyone involved in a session to become a joker, able to replicate these methods as needed elsewhere. Achieving this level of versatility requires individuals to “demechanize” their bodies and minds, moving away from the repetitive, optimized behaviors ingrained by factory work or service industry roles. This involves unlearning the automatic, insincere smiles given in service encounters, prompted not by genuine feeling but by professional training and expectations. Theatre of the Oppressed encourages an unlearning of these mechanized gestures and expressions, fostering a more authentic engagement with one’s emotions and actions.

Upon demechanization, individuals can begin to explore and rehearse responses to oppression. This exploration allows for a reclamation of desires, bodies, and a sense of equality, challenging the imposed limitations and expectations of oppressors. This is the essence of Theatre of the Oppressed—using theatrical methods to embody and confront real-world oppressions, thus transforming both understanding and action.

Applying these concepts to service design, we’ve experimented with using Theatre of the Oppressed as an alternative to traditional methods like bodystorming and experience prototyping. This approach, which we’ve termed interaction design theatre, enables the creation of service solutions directly addressing oppression. For example, our design students developed an LGBT safety alert app called “PomboCop” during a theatre session. This concept, inspired by real-world violence scenarios, utilizes a speculative design to emit deterrent sounds near aggressors targeting LGBT individuals. This innovative approach underscores the power of Theatre of the Oppressed in inspiring real-world solutions and interventions within the realm of service design.

Additionally, we’ve developed structured activities to publicly debate controversial features in service design, such as the “ride silence” option introduced by ride-hailing apps like Uber in Brazil in 2019. We conducted a theatre session to question the ethics of allowing a passenger to request silence from a driver before even meeting them, especially when this service requires an additional fee not included in Uber’s standard offerings. This scenario raises questions about the societal implications of commodifying silence and whether such practices should be encouraged. These discussions were facilitated through forum theatre sessions, inviting audience engagement and debate.

Following the COVID-19 isolation measures, we adapted to remote forum theatre sessions, creating spaces for designers to critique and reflect on the precarity of design work. One scenario involved the Fantastic Design Factory, a fictional setup managed by artificial intelligence that solicits design work at exceedingly low prices, treating human designers as if their outputs were the products of automation — a practice known as heteromation. This notion of invisibility behind digital interfaces exposes the devaluation and exploitation inherent in such work arrangements.

Shifting focus to more distanced work inspired by the Theatre of the Oppressed, I’ve been exploring how this metaphor can be applied beyond direct theatrical engagement. Here, the principle is that everyone contributes to all necessary tasks, fostering a dynamic where roles and responsibilities are fluid, thereby preventing alienation from repetitive tasks. This approach ensures a comprehensive understanding among participants, avoiding the isolation that comes from specialization. This strategy not only democratizes the work process but also enriches the collaborative experience, encouraging a more holistic and inclusive approach to service design and problem-solving.

For over a decade, we have been observing the collaborative efforts of cultural producers in Northeast Brazil, who utilize a digital platform we developed specifically for organizing social movements and small cultural collectives. This platform enables them to identify shared skills and capabilities that can be transformed into services for their communities. This approach shifts the focus from responding to demand to leveraging what they can collectively offer. Furthermore, we’ve incorporated solidarity economy mechanisms to facilitate the exchange of these services without relying on official currency, allowing for the creation of new ventures based on available skills and not on governmental funds.

This model embodies the principle of “everyone does everything” from Theatre of the Oppressed, promoting skill sharing and the fluidity of roles within the community. It creates a system where any service buyer can also become a service provider, fostering a self-sustaining cycle of exchange and collaboration. Though this concept may seem complex, it illustrates the transformative potential of reimagining economic and social structures through collaborative design.

A more tangible example of this approach is a coalition design project initiated by one of our design students, focusing on women coffee workers in rural areas. Noticing their absence from product packaging and branding, she facilitated a connection between these producers and urban coffee sellers, such as baristas. This collaboration not only highlighted the contributions of women in the coffee industry but also addressed underlying issues of sexism by making their work visible. Through these efforts, participants across the coffee production chain could unite to challenge and change the narrative around their labor and contributions.

In their collaboration, these women aimed to challenge the male-dominated leadership in the coffee industry. They even engaged with a city council member, aiming to impact the policy-making process. This effort is just one of many instances reflecting the principles of the joker system, where traditional separations between the visible (front stage) and the hidden (backstage) aspects of work are dissolved. This system encourages everyone to participate in all tasks, thereby preventing the alienation often experienced by experts in highly specialized roles. It fosters a culture of visibility and shared responsibility.

The Joker system also proposes that those in positions of power or privilege can become allies to the oppressed, provided they recognize their own positions within structures of oppression. Our research has explored the role of designers within capitalist societies, suggesting that designers often inadvertently play the role of oppressors. This assertion challenges conventional perceptions and highlights a phenomenon we’ve termed userism. This concept notes that marginalized groups are frequently categorized as users rather than creators, underscoring a systemic bias in design and technology fields. An examination of scholarly databases reveals a stark disparity in the representation of black users versus black designers, illustrating a broader trend of exclusion and marginalization. This insight underscores the need for a reevaluation of roles within the design community, advocating for a more inclusive and equitable approach that recognizes the contributions and potential of all individuals, regardless of their background.

Designers, while integral to the creation process, face their own form of oppression, albeit in a different context from those they design for. They are typically wage workers, reliant on salaries to sustain their livelihood, contrasting sharply with design capitalists who possess substantial resources, ensuring their survival even in business downturns. This dichotomy reflects the enduring class distinctions within capitalism—the bourgeoisie, who own the means of production, and the proletariat, who sell their labor.

This scenario allows designers to empathize with users, particularly those marginalized by systemic biases, through shared experiences of oppression, albeit in varied capacities. It’s an uncomfortable truth that the design industry, by prioritizing certain voices over others, can perpetuate user oppression, as evidenced by the disproportionate representation of certain groups in user demographics compared to their presence in design roles.

Addressing this, the Designing & Oppression Network, established in 2020, aims to uncover and challenge oppression within the design field through both online and in-person workshops. These sessions explore the dynamics of oppression and privilege, employing innovative methods like remote theater of the oppressed using 3D puppets to simulate oppressive scenarios, though acknowledging the deeper impact of face-to-face interactions.

The forthcoming ServDes Conference in July 2023, set in Rio de Janeiro—my and Fernando’s hometown—will feature a workshop on the Theater of the Techno-Opppressed, co-hosted with Bibiana Serpa, a fellow founder of the Designing Oppression Network. This event represents an open invitation to engage with these critical issues, fostering a dialogue aimed at reshaping the design landscape into one that is more equitable and just.

Thank you for your attention. I look forward to discussing these ideas further and exploring how we can collectively address the challenges of oppression within the design community and beyond.