Abstract: Decolonizing design confronts the deep-rooted structures of colonialism that still shape international aesthetics, production, and trade relationships. The coloniality of making divides “thinking” in developed nations and “making” in underdeveloped ones, generating a nostalgic feeling for colonial styles thought and made for others. By fostering autonomous development and critical consciousness, decolonizing design encourages innovative solutions like open-source modular systems that emphasize thinking and making for self. This process aims at an equitable relationship between nations, where creativity and collaboration thrive, redefining design as a part of national liberation projects and international prosperity.

Pre-recorded talk for the ADA Awards Seminar, hosted by the Beaconhouse National University, Pakistan.

Video

Audio

Full transcript

Hello, people from Pakistan; here is Frederick van Amstel. I am speaking from Florida.

As you can see, I cannot be there in person to join this grand celebration you are hosting, but I hope to make a small contribution to your seminar through this pre-recorded video.

My topic is decolonizing design. Before I go to that, I need to state my positionality within this topic. I am a Brazilian person. I grew up in that country, and I am also a big soccer fan—well, not that big—but I support my nation in soccer because it is one of the biggest soccer teams in the world. And Pakistani people also know this—you have the best soccer fans, at least in the Lyari neighborhood in Karachi. I was curious to know more about this village and why they supported Brazil so much in the last World Cup. Well, I know very little about Pakistan. I hope the next time I can be there and learn more about your country.

Besides Lyari’s Brazilian soccer fans, the second thing I know about Pakistan is that it shares a history of colonialism with Brazil. Pakistan was colonized by the British, whereas Brazil was colonized by the Portuguese. They have very different colonization styles, goals, purposes, outcomes, results, consequences, and so on. However, we can generalize some of the fundamental structures of colonial relationships.

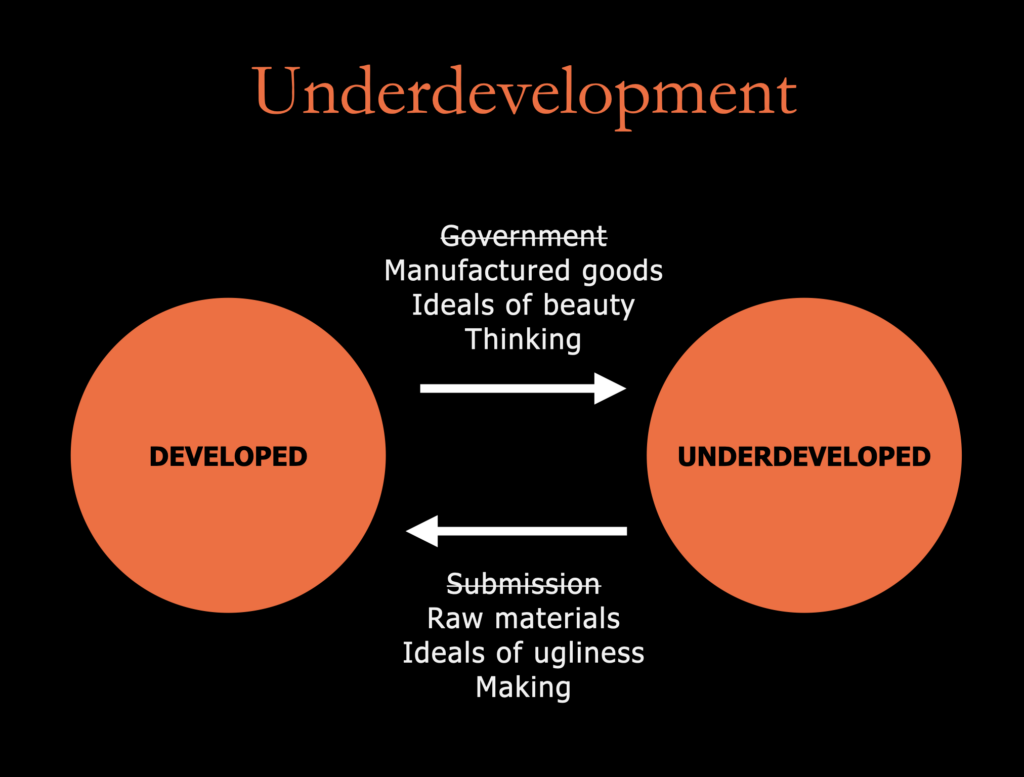

Here is a structural diagram of how the colonialism relationship unfolds through time. There is the metropolis that concentrates all the power and the thinking and the possibility of devising or directing what a colony should do. In return, the colony will give back something to the metropolis. In general, the metropolis imposes government, manufactures goods, ideals of beauty, thinking, and many other things, whereas the colony gives back submission, raw materials, ideals of ugliness, and making.

For design, what matters the most is this divide between thinking at the metropolis and making at the colony. Even when traditional or historic colonization has been overcome through independence and liberation wars, the structural relationship between those two worlds remains.

It’s now sometimes called underdevelopment or developing nations or whatever people call it. It doesn’t change fundamentally their relationship—it is still two different worlds. So, the metropolis is now the developed nation or the developed world, whereas the colonies are now underdeveloped nations or developing nations.

There’s no longer an imposed government on the developed world, no longer submission. However, there is still unequal trade in manufactured goods for raw materials, ideas of beauty, ideals of ugliness, and thinking and making, which are still pretty much concentrated. There is a little bit more distribution, but inequality remains.

The impact of this on design is that we see these very nostalgic styles in the former colonies that are still very difficult to overcome. Even if this furniture system has been designed and built in Brazil, it still embodies the Portuguese colonial style, which I sometimes call the coloniality of making. Even though we overcame historical colonialism, we could not get rid of this coloniality of making.

The result is something that looks beautiful for someone who thinks with the colonial framework of what is beautiful, what is good, and what is nice to have at home. But it looks ugly for someone looking to overcome this nostalgic feeling.

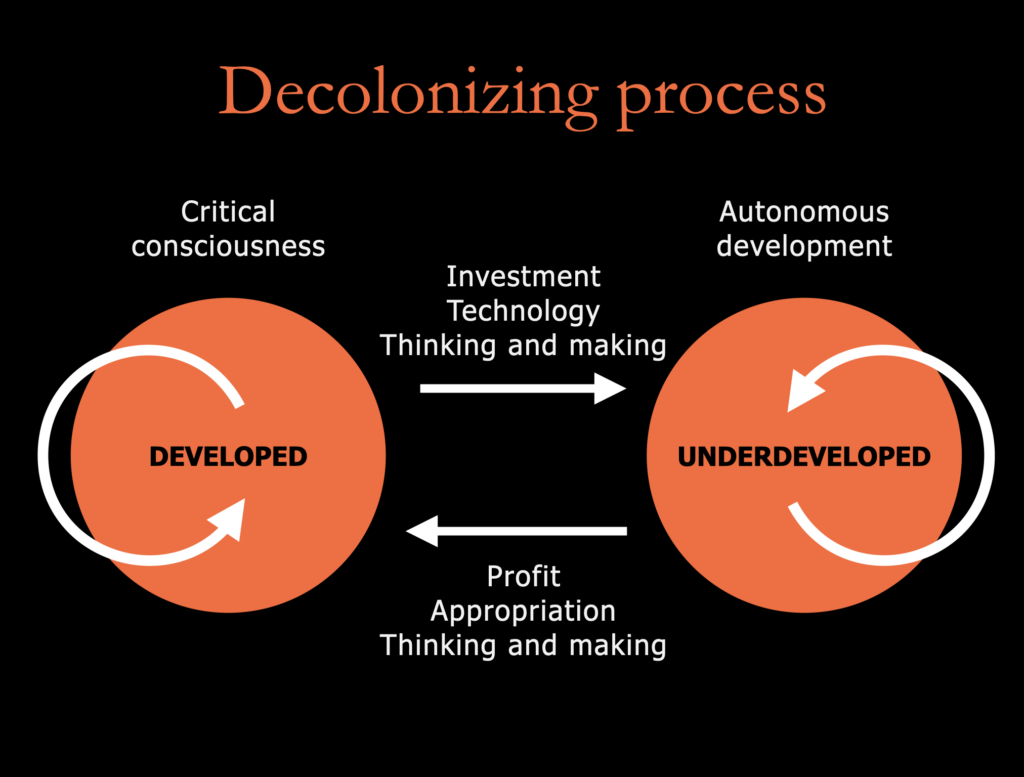

Decolonizing is when we start in the underdeveloped world to become more conscious of the coloniality of making and working to design and develop autonomously. Through this process, we realize we don’t need to rely that much on the developed nations. Nevertheless, we don’t cut ties totally—that would be very radical, and maybe it wouldn’t work or last for long, especially in a world that depends significantly on globalization, trade, and exchanges.

Instead of cutting ties totally, decolonizing is a process that may take a lot of time, but it depends mostly on what the underdeveloped world does for itself. In comparison to the situation of underdevelopment, there is an extra loop of development where the former colony develops for itself. That’s what the decolonizing process is at the beginning, in the first phase.

Here is an example of how decolonizing impacts design. I’ve got these marvelous creative students, Conrado Dembinski and João Taran Araújo, who designed SURU, a decolonial modular furniture system that contrasts very much with the traditional Portuguese colonial style.

As you can see on the left side, this style is still alive in many old institutions like the UTFPR, where these students studied. On the right side, you see the decolonial furniture system—based on open source, ready-to-make, and multi-modular. This pretty flexible furniture system breaks with the traditional colonial styles’ aesthetics and function.

But there’s a second phase in the decolonizing process that must be held in developed countries, developed nations, which is precisely what I’m doing here at the University of Florida. I’m helping to consolidate this decolonization process by building a critical consciousness of what’s happening in our worlds.

The fact that underdeveloped nations are developing by themselves and growing much faster than developed nations and displaying this sheer flourishing of creativity and originality is not something to be envied, destroyed, curtailed, or blocked. That’s the future for the developed nations. We need to establish a relationship between many worlds that is equal and thriving for all.

In this stage, I envision a future where developed nations will invest, transfer technology, and share styles with the underdeveloped. The developed will generate profit from these investments and appropriate technologies, change them for their purposes, and deliver great designs—not just for themselves, not just for the underdeveloped world, but even designs for the developed world.

Here, you can see how I realize this vision with my students in our graduate program called MXD. We have students from many different nations worldwide, including the Middle East, Asia, and South America. These students obviously have various backgrounds and are curious to know how the United States sees itself and their worlds in the local news. Hien Phan, one of my current MFA students, hosted this workshop on mapping the immigration patterns of our different students and how they felt impacted by the local news.

The challenge is to develop critical consciousness of the prejudice that sometimes United Staters have against themselves. They may believe that just because you come from a certain country, you are a terrorist, or you are a potential spy, or you are someone who is going to steal their jobs. Understanding how this is part of this larger framework of the decolonizing process is key for these students to develop autonomously and design from critical consciousness.

So, in a nutshell, decolonizing design for me means designing from critical consciousness and for autonomous development. We have some academic references you can check to learn more about my work as a design scholarship. Thank you.

References

Van Amstel, F. M. C. (2023). Decolonizing design research. In: Rodgers, Paul A. and Yee, Joyce (Eds). The Routledge Companion to Design Research (pp. 64-74). Routledge. https://www.doi.org/10.4324/9781003182443-7

Mazzarotto. M., Van Amstel. F. M. C., Serpa, B. O., Silva, S. B. (2023). Prospecting anti-colonial qualities in Design Education. V!RUS Journal, 26, 135-143. Translated from Portuguese by Giovana Blitzkow Scucato dos Santos. Available at: http://vnomads.eastus.cloudapp.azure.com/ojs/index.php/virus/article/view/833

Noel, L.-A., Ruiz, A., van Amstel, F. M. C., Udoewa, V., Verma, N., Botchway, N. K., Lodaya, A., & Agrawal, S. (2023). Pluriversal Futures for Design Education. In She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation (Vol. 9, Issue 2, pp. 179–196). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sheji.2023.04.002

Dembinski, João Conrado Santana de Lima; ARAÚJO, João Victor Tarran. SURU’BA: Sistema Utilitário Recombinante Utópico-Universal Baseado na Autonomia. 2022. Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso (Bacharelado em Design) – Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, 2022. http://repositorio.utfpr.edu.br/jspui/handle/1/35099

Winschiers-Theophilus, H., Smith, R. C., Amstel, F. V., & Botero, A. (2025). Decolonisation and Participatory Design. In Smith, R. C., Loi, D., Heike Winschiers-Theophilus, H., Huybrechts, L. & Simonsen, J. (Eds.). Routledge International Handbook of Contemporary Participatory Design. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003334330