Abstract: Userism in service design manifests as a group of humans reduced to be users (and only users) of a given service. Userism prevents these people from cocreating, codesigning, and coproducing services. Transnational (often colonialist) digital services are a case in point; however, userism also appears in analog interfaces. The systemic aspect of userism refers to the broader implications of producing services as something to be used instead of exchanged. For instance, the same person may be treated as a user by multiple services, including the services in which this person actively produces it. As a result, work may become invisible to the very worker, who believes to be just using a service. In the long run, this may result in a society of alienated users who don’t understand their stakes in it. Service design can do something to recover this degrading citizenship, but it must first eliminate its central tenets: user-centered design, user research, and user experience. After that, anti-oppressive ways of doing service design may become more evident.

Guest lecture at the Design Justice and Emerging Technologies course at TU Delft, led by Fernando Secomandi.

Video

Audio

Full transcript

Thank you for having me today, Fernando, and everybody else there at TU Delft, Industrial and Design Engineering. I’m happy to talk to you, share my research, and especially highlight some joint activities I’m working on with Fernando to open new research avenues. This presentation will be quite dense and compact, and I expect that if you want to dig deeper into it, you check my website. You can find many of my lectures and publications there, openly available.

Let’s start from the ground up by sharing the sources of this presentation. I’m combining three main sources. It’s a meditation or a further reflection on these recent publications. These are still forthcoming.

Systemic oppression in service design is a book chapter of Systemic Service Design, edited by Mari Suoheimo, Peter Jones, Sheng-Hung Lee, and Birger Sevaldson. It’s going to provide a very interesting overview of different systemic design approaches. We are bringing up userism as part of this discussion. Also coming up next year, The Bloomsbury Handbook of Service Design: Plural Prospects and Critical Contemporary Agendas, edited by Lara Penin, Alison Prendiville, and Daniela Sangiorgi, is another very important consolidation of new discourses emerging in this field. Together with Fernando, I co-wrote a chapter titled Collective embodiment in service interfaces. These two books will definitely help reshape the field of service design by addressing contemporary issues, especially regarding systemic-level contradictions. We are not just dealing with problems confined to one specific design space, with defined boundaries and constraints; instead, we are addressing societal contradictions, also known as wicked problems.

The most important reference for this particular presentation is a journal article previously published by Rodrigo Gonzatto and me in the ASLIB Journal of Information Management. It’s about user oppression in human-computer interaction, where we define what userism is. I know that many of you have read this article, but I’d like to provide a quick overview of it so we’re on the same page for this discussion.

In human-computer interaction, userism is characterized as an oppression that reduces humans to users—and only users—so they cannot develop further than being a user of a computer. For example, they cannot progress to becoming a developer, a designer, or someone with more agency over the functionalities and purposes of the computer.

Here are some examples extracted from the discourse in human-computer interaction, meaning books, articles, and conferences. They frequently transform different kinds of humans into users. Every human becomes a specific type of user, depending on the type of agency that is being reduced.

For instance:

- A poor person becomes a “low-income user.”

- An elderly person becomes a “laggard user,” someone who takes more time to adopt new technologies.

- A disabled person or person with disabilities becomes an “assistive technology user.”

- A voter becomes a “social media user.”

Think about the consequences of this. An immigrant like me in the United States becomes a “translation app user,” and that’s all I become. Everything else—the contradictions of being an immigrant—is disregarded in this kind of reduction.

And last but not least:

- A woman becomes only a “menstrual application user,” even though some women do not menstruate, such as trans women.

- A gay person becomes a “heavy user of dating systems.”

I’m emphasizing these last two examples because there’s a lot of prejudice involved in defining people this way. But that’s exactly what happens with userism: people are boiled down to that simplistic relationship with technology. Under userism, people’s identities are reduced to needs that design can address. They are stripped of history, body, voice, and rights. This reductionism constitutes an oppression, which is why we define userism as user oppression.

Does service design contribute to userism? Our findings from past studies have shown consistent evidence that userism manifests in human-computer interaction. Some might argue that service design is a subfield or spin-off of human-computer interaction. But service design is not necessarily the same, even though it draws heavily from human-computer interaction. Still, we find this userist language, these terms, and these reductions also occurring in service design—perhaps to a lesser extent.

For instance:

- Poor people are often seen as “public transport users,” with everything else about poverty—such as class struggles—ignored.

- Patients are reduced to “health service users,” with everything else in their lives ignored, except what concerns their use of the service being designed.

- Students, like many of you, are viewed as “educational service users.” Educational policies increasingly treat education as a service, turning students into customers who purchase knowledge—an odd paradigm for education.

- Citizens are often reduced to “public service users” in liberal discourses on smart cities and public policy design.

This reduction is particularly striking because citizens can do much more than use public services. They can influence policy, vote, and co-design in participatory democracies. However, everything is becoming a platform, including government and educational institutions. Teachers, for example, are being reduced to platform users—whether it’s YouTube or communication platforms like Teams, which we’re using now. I find this troubling because platforms own our knowledge and thinking, structuring it in ways that turn us into users. Customers, workers—everyone becomes a platform user. This broader phenomenon ties service design to the neoliberal platformization of society, where everything is a platform, and members are reduced to users. Userism aligns with this platformization process, where digital technology becomes the foundational infrastructure for producing any kind of service.

However, this is not just about language. Renaming the design approach won’t change the underlying contradiction. There’s a lot of discussion in human-computer interaction, service design, and design research about moving beyond user-centered design. For example, some advocate for “people-centered,” “planet-centered”, “more-than-human-centered”, “whatever-centered” design to address anthropocentrism and climate change. But the issue is not what’s at the center—it’s centrality itself.

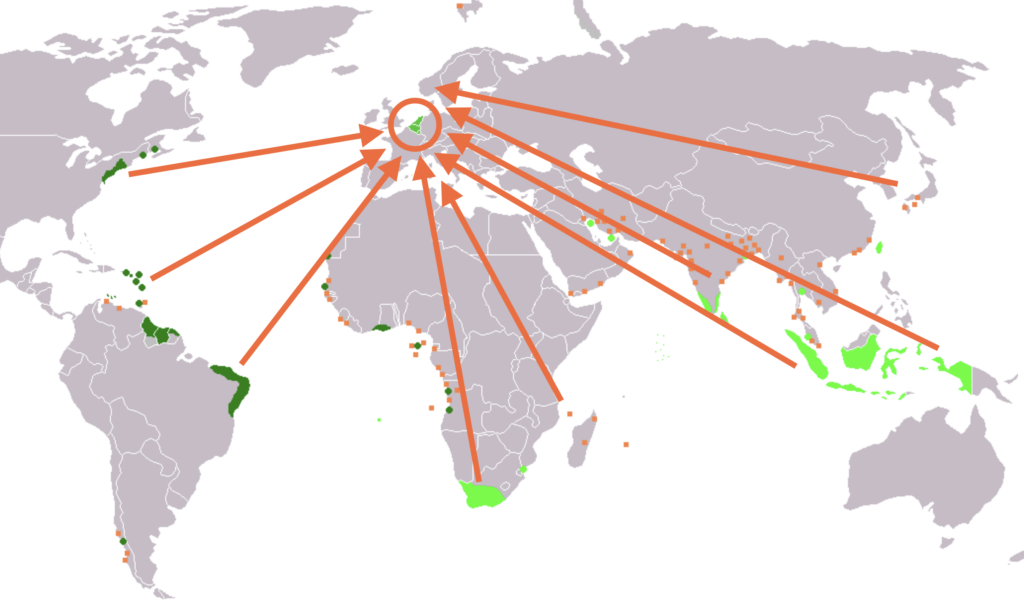

Yes, centralization is the origin of userism and many other oppressive systems, and it was globalized through colonialism. Here, I’m showing a picture of the former Dutch colonial empire. I’m really poking at you because you are located in the Netherlands. I personally have ancestors who were colonial officials in Indonesia, for example, so I feel a strong responsibility for this history and legacy. It’s important that we decentralize this pattern because colonialism over-beneffited the Netherlands. You’re standing on an accumulated history of privileges, but your moral duty is to share that privilege and turn it into a human right. This is what we’re trying to address in design research: what is our role in this process of decolonization?

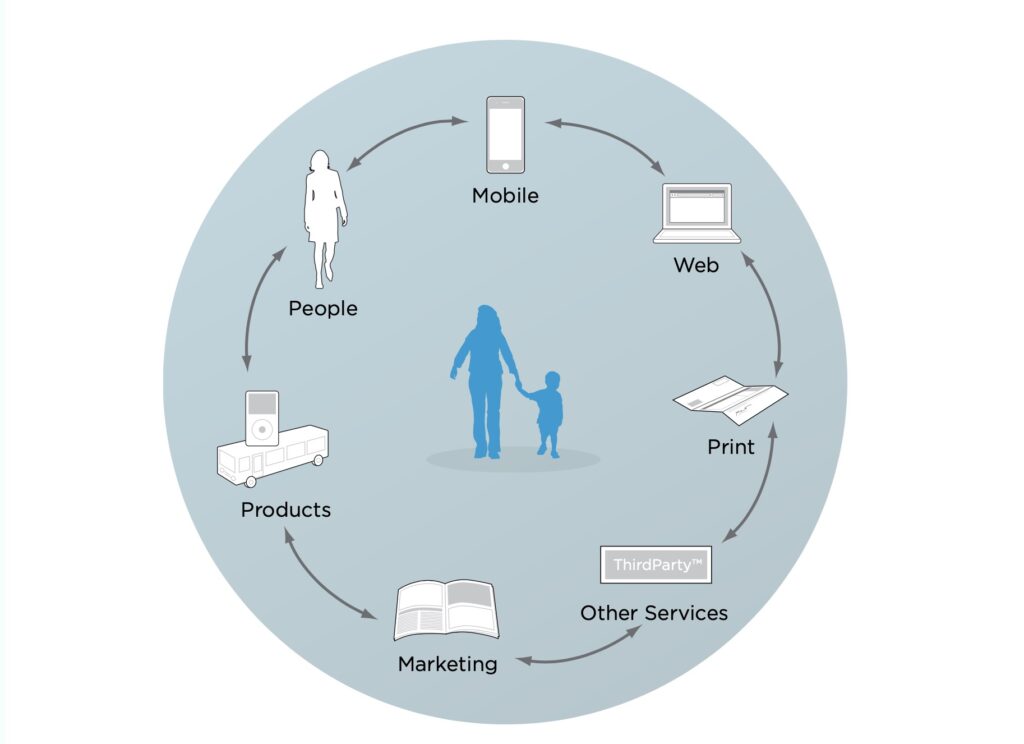

Coming back to service design, the first step is to understand how service design centralizes certain humans and marginalizes others. I cannot go into too much detail about how this works, but I want to point you to some classic references, such as the theater metaphor by Grover and Fiske (1992) and the service blueprint proposed by Shostak (1984). These are foundational concepts in service design, and they propose documentation and practices that are still in use today. While perhaps not as rigid as they once were, many service designers and researchers still rely on these fundamentally userist tools. They define the user as someone who merely enjoys an experience with a service, without co-producing or contributing directly to the creation of that service. Users are seen as passive recipients of experiences designed by providers and designers.

Here’s a more contemporary example of work that reproduces this baseline idea. A widely used book on service design introduction by Polaine and colleagues (2013) still draws on this theater model and the concept of touchpoint design integration—a contemporary term for this approach. The service touchpoints are designed to provide a consistent user experience. User experience is often praised as a design quality, but it reinforces alienation, limiting people to being only users. Whenever you design a user experience, you keep people within the bounds of userism. While it might seem beneficial, this has systemic effects: it fosters a society where everyone is limited to having user experiences.

Think again about platformization—people no longer have citizen experiences or moral experiences; they’re reduced to having user experiences. When interacting with computers, if interfaces are designed as stages in a theater, where multiple agents (human or non-human) play roles, this can blur the distinction between these agents. Brenda Laurel anticipated this in her book Computer as Theater (1993). She predicted that we would interact with humans and non-humans through similar interfaces, sometimes becoming confused about whether we’re dealing with a person or a computer system.

Over time, this kind of interaction leads people to feel as though they are interacting with computers instead of other humans. For example, you press a button that affects another person, but you’re unaware of the impact because you perceive the interaction as occurring solely with a computer. Layers of abstraction, exacerbated by platformization, obscure whether real people are involved on the other side. This is why human-computer interaction remains a crucial topic for service designers, especially those working with digital technologies—something almost unavoidable in service design.

We must recognize the legacy of human-computer interaction theories and practices that form the foundation of the field. These ideas are often rebranded with new names, but their essence remains unchanged. For instance, user-centered design is still pervasive, even if it’s renamed as product-service systems. It’s still based on the idea that the user is the core focus of design.

Importantly, not all people become users—only some do. User-centered service design has the troubling implication of encouraging people to treat marginalized individuals as mere tools or resources, not necessarily as users. Marginalized individuals can appear as service providers hidden behind interfaces or as non-users—people excluded because of accessibility barriers, language differences, or lack of access to resources. Even when these individuals don’t directly interact with systems, their data might still be harvested to train artificial intelligence. This highlights a broader systemic contradiction: userism reduces people to tools or things.

If this contradiction is not addressed early, they manifest in public spaces, sometimes with tragic outcomes. Let me share an example from Brazil. A popular food delivery platform, iFood, allows customers to order meals. A black courier in Rio de Janeiro was delivering food to a white woman who claimed he was ten minutes late and that her food was getting cold. She felt entitled to whip the courier—a horrifying reenactment of the violent, racist dynamics of slavery. While the woman was excluded from the platform, and the courier received public support, the platform itself remains structured around the same provider-customer relationship. This structure allows and even encourages service users to perceive themselves as being served by systems rather than real people.

And here’s the opposite situation—when the provider is actually oppressing the user. There was a case of a woman who was raped because of a Uber ride in Belo Horizonte. The driver noticed she seemed unconscious and unable to wake up and walk to her house. Instead of helping her regain consciousness or ensuring her safety, he simply carried her over his shoulder, left her in front of her house, and drove off. He didn’t open the house for her or stay to ensure she was safe. A few minutes later, a motorcyclist passing by saw the unconscious woman, stopped, and raped her. The motorcyclist was sentenced to ten years in prison for this horrific crime. However, the judge declared the Uber driver not guilty because he was merely following the rules of the app. The argument was that the app should have clearer rules to prevent such incidents.

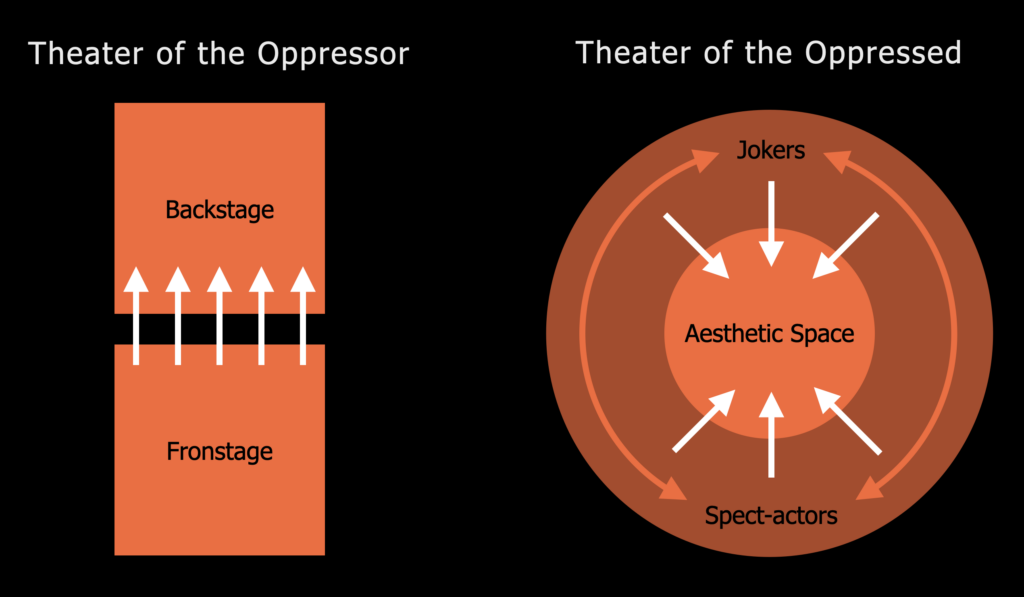

This is undeniably a service design disaster. It stems from the userist ideology embedded in how computers and services are designed. When systems are designed this way, they effectively become a “theater of the oppressor.” If that’s the case, we can work to build an anti-userist theater model for service design, inspired by the Theater of the Oppressed—a method developed, organized, and systematized by Augusto Boal, a Brazilian dramaturg. In the 1970s, Boal fled the country in exile due to political persecution. During this time, he developed a systematized method of creating participatory theater among amateurs, allowing anyone with a political message to express it through theater.

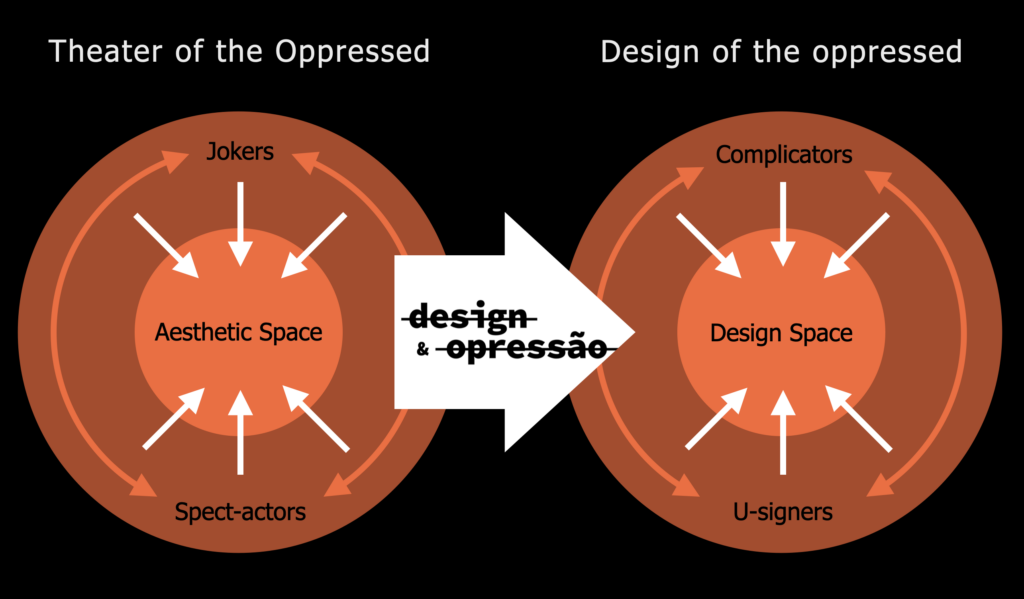

The Theater of the Oppressed uses a completely different production process compared to traditional theater. It doesn’t involve preparing a staged performance in the background and then presenting it to an audience with the aim of convincing them of something—such as making them realize how they are being oppressive. It’s not an ideological theater. Boal criticized traditional Greek theater, where the stage was used to create “magic” moments. Service design often mirrors this model, with its emphasis on orchestrating user experiences. In contrast, the Theater of the Oppressed transforms the audience into “spect-actors”—potential actors who join a dynamic, permeable space that is not a traditional stage. This participatory space allows them to enter and alter the play in real-time. The process is facilitated by “jokers,” who are behind the scenes organizing and ensuring that everyone can participate meaningfully.

Inspired by the Theater of the Oppressed, we’ve conducted several experiments to overcome the oppressive theater model in service design. For example, Uber Comfort—a premium service—introduced a “silent ride” feature. This allows users to pay extra for the option to request that drivers not talk to them. We found this feature to be strange and contradictory, especially in Brazil, where a talkative culture creates basic expectations of interaction between passengers and drivers. To explore the implications, we rehearsed this situation during a Forum Theater session at a human-computer interaction conference. Many participants became concerned about how this feature could oppress both users and drivers—who are themselves platform users.

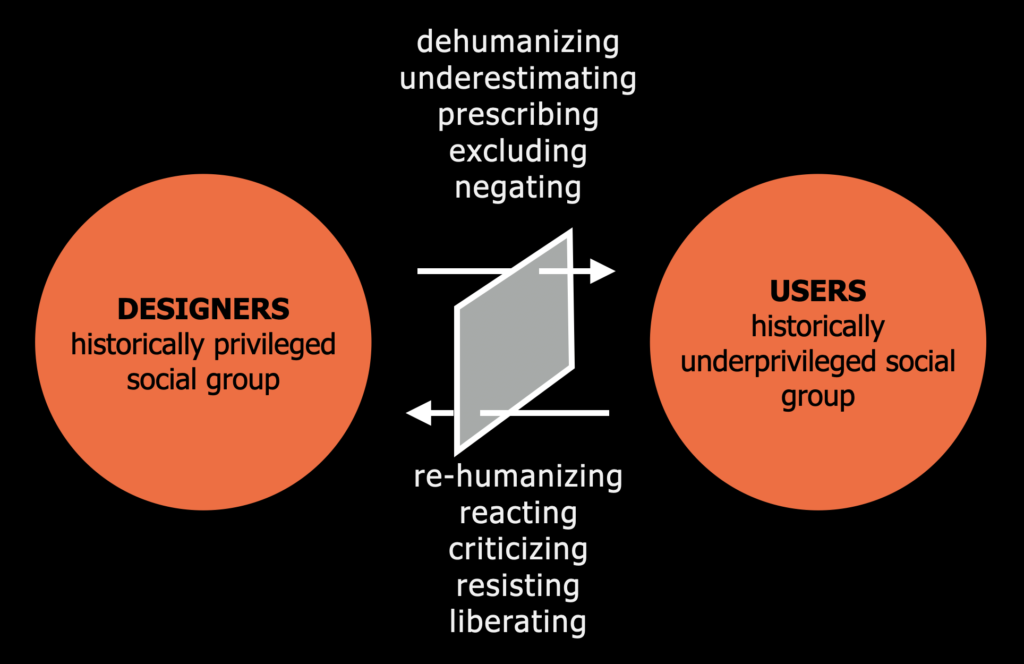

We addressed this case in a forthcoming book chapter I mentioned earlier. However, the broader question remains: how do we tackle the systemic aspects of userism? Addressing a single instance is not enough, as userism spreads across many interactions. The germ cell model of userism, which Gonzato and I introduced in our paper, illustrates this. It shows how historically privileged social groups of designers interact with historically underprivileged users through computers. This interaction often leads to the dehumanization of users by designers. However, users don’t passively accept this oppression. They react and strive to overcome it through strategies of re-humanization and resistance.

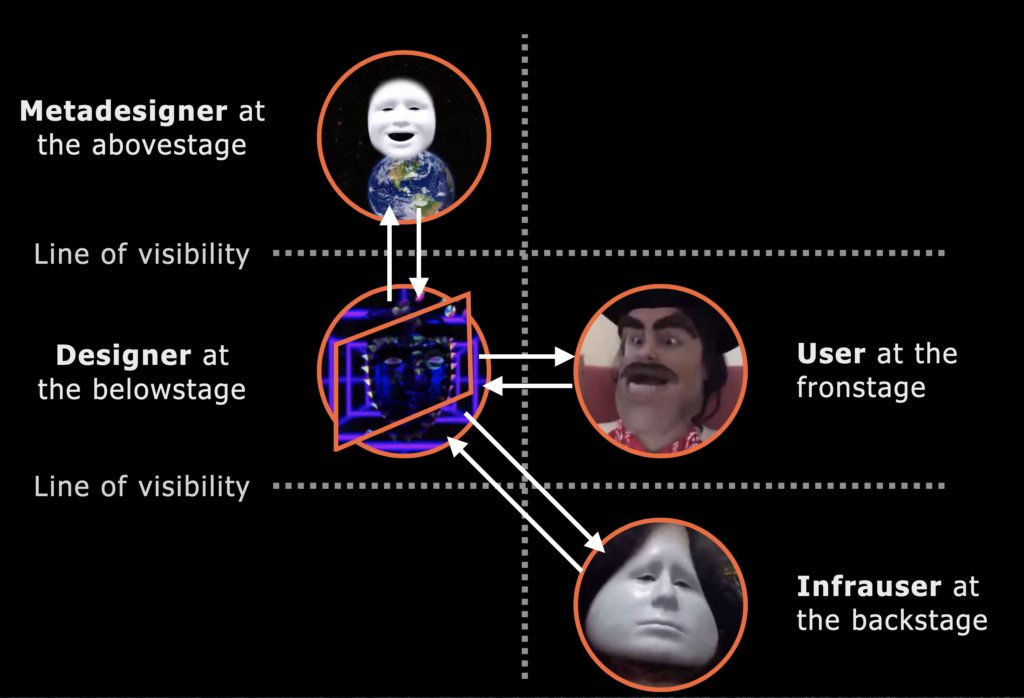

In another forthcoming book chapter, written with Fernando and Bibiana Serpa—fellow members of the Design & Oppression Network—we present a more nuanced understanding of userism in service design. Above designers, there are metadesigners: capitalists, directors, CEOs, and other wealthy individuals who set conditions and constraints for designers, limiting their freedom. At the same time, users themselves can oppress infrausers. These are people who may not consider themselves users or workers but instead see themselves as casual users or just “a dude on the internet.”

To convey the systemic nature of userism to design students in Brazil, we organized a speculative design theater on the precarization of design labor in digital services. In this scenario, we imagined a system where designers were exploited in ways similar to couriers and drivers on labor platforms. In our speculative scenario, an artificial intelligence served as an intermediary between clients and designers. When a client requested a logo, the AI promised to deliver it in five minutes. During this time, the AI hired a human designer to complete the work for just $5 per hour—a precariously low wage. We created a character called the “lumpen designer” to represent the exploited laborer. This designer protested the low pay, asking for $10 instead. The AI responded, “If you don’t want the job, I’ll find someone else willing to work for $5.”

The AI embodied neoliberal capitalist ideology, making its oppressive mechanisms more transparent. While this was speculative, it reflects real-world dynamics on crowdsourced design platforms (like 99designs.com), where many Brazilian designers are forced to work due to a lack of better opportunities. In our story, the lumpen designer eventually tries to organize a strike with other designers. The strike doesn’t succeed, but it leads to an unexpected encounter with the meta-designer—the person behind the AI platform. This interaction mirrors a scene from The Matrix, where Neo meets the Architect.

However, the conversation takes an odd turn. Instead of just discouraging the strike, the meta-designer invites the lumpen designer to co-design the platform, offering Amazon gift cards as compensation. “Help us improve the platform,” the meta-designer says, “and these gift cards will be worth more than your current pay.” The lumpen designer refuses, stating, “I don’t want to co-design the platform. I want better pay and basic worker rights.” The meta-designer dismisses this as “old-fashioned,” arguing that capitalism has evolved. “If you don’t like this platform,” they suggest, “why not study meta-design like I did and create your own platform? Become an entrepreneur yourself.”

Well, the situation is pretty grim for the lumpen designer. He becomes depressed, and the play stops there because the whole purpose of the Theater of the Oppressed is to stimulate people to take action and not let them think that easy solutions are possible.

Here’s the Fantastic Design Factory seen through our systemic userism model I presented earlier. In this model:

- The meta-designer works at the “above” stage, designing and receiving data from the AI, which plays the role of a designer.

- The AI, though not a person, takes on the role historically performed by humans.

- This “designer” distributes work that originates from the user or client (at the front stage) to the infra-user (at the backstage).

- There is no direct communication between user (client) and infrauser (human designer)

We aimed to provoke design students to consider that if they don’t resist userism, they will inevitably become users themselves. In fact, most already are. Often, you think you’re a designer, but when you’re sitting in front of an Adobe product, you’re just a user—or worse, a user who doesn’t even recognize their position as a user. Centralizing design or involving users as co-designers alongside designers or even metadesigners, as in the Fantastic Design Factory, does not fundamentally change this userist structure.

Is it possible to design services that resist systemic userism? We’ve been working on this for years. One example is the Corais Platform, co-designed by Brazilian designers and activists from 2011 to today. It’s an anti-colonial alternative to platforms like OpenIdeo.org (a crowdsourced problem-solving and open innovation platform) and even Google Drive. At one point, Corais offered more features than Google Drive. However, competing with tech giants has become increasingly difficult, especially given the digital colonialism they propagate—not only in Brazil but globally, including in the Netherlands, where Dutch users are also victims. For example, right now, we’re using Microsoft systems designed in the United States.

Corais incorporates a metadesign project that allows any platform member to participate. Users can collaborate with meta-designers to create new features. I co-authored a paper with Isabela de Siqueira detailing how self-managed services were redesigned using participatory metadesign approaches. One example is a social currency feature that facilitates transactions outside traditional capitalist money-based systems. It enables collectives without financial resources to operate based on solidarity relationships.

While this approach combats userism, it doesn’t entirely eliminate its structures. Instead, it enables interactions that allow people to shift roles temporarily. For instance:

- I’ve been a meta-designer since the project began, designing the platform itself.

- Other designers have joined temporarily as meta-designers.

- Even users have participated in meta-design activities.

Designers primarily use the platform to design for others, while users are often the beneficiaries. Infrausers—such as elderly individuals who can’t use the platform—still influence the actions of both users and designers. For example, they might encourage others to use the platform on their behalf. This decentralized design strategy fosters connections between the roles involved in service production. Metadesigners interact with users, users interact with infrausers, and so on. But there are still differences and boundaries between designers and users. We documented this approach in the book Design Livre, published in 2012. While it hasn’t been translated into English, a Spanish version is available. The book serves as a manifesto for the Corais platform.

Reflecting on this work over the years, we’ve realized it’s not enough. Free software, open-source and its equivalents in design—like open design or even earlier versions of critical participatory design—combat userism by empowering users to transcend their roles or avoiding the term “users” altogether, calling them “participants.” However, these approaches don’t necessarily address other forms of oppression, such as capitalism, racism, sexism, colonialism, or ableism. These systemic issues still contribute to placing people the oppressed in the subordinate position of user even if you treat them as a participant. If you don’t address these broader oppressions, you’re merely trading one form of oppression for another.

Augusto Boal’s words are crucial here. In his book Games for Actors and Non-Actors—a practical and accessible introduction to the topic—he insists that “the struggle against one oppression is inseparable from the struggle against all oppressions, secondary as they may seem” (p.268). So, if someone says userism is a secondary concern compared to others, we can agree. It might even be tertiary. However, in a society increasingly reliant on digital technologies and platforms, failing to combat userism allows other forms of oppression to persist. They may fade from view or become less visible, but they won’t disappear.

This is why we draw inspiration from the Theater of the Oppressed and on other sources raised by the Design & Oppression Network. We’re developing an approach we call Design of the Oppressed. In this method, we replace facilitators with complicators—individuals who deliberately complicate situations to help participants recognize and understand the oppression present in their practices and activities. That’s what I’m currently doing in my work. We collaborate with u-signers, a hybrid role combining user and designer characteristics, similar to Boal’s spect-actors (a mix of spectators and actors). Our aim is to transform and open up the design space, making it more transparent and permeable so people can enter, leave, and collaboratively reshape whatever is being designed.

The references I mentioned will be available on my website soon. If you’re interested in discussing this topic further, please feel free to ask me questions. I’m not sure how much time we have left, but thank you for your attention so far.

References

Van Amstel, Frederick M. C., Serpa, Bibibiana, Secomandi, Fernando. (2025). Systemic oppression in service design. In: Suoheimo, M., Jones, P., Lee, S., Sevaldson, B (Eds). Systemic service design. Routledge. http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9781003501039-7

Van Amstel, Frederick M. C., Secomandi, Fernando. (forthcoming) Collective embodiment in service interfaces. In: Penin, L., Prendiville, A., Sangiorgi, D. (Eds.). The Bloomsbury Handbook of Service Design: Plural perspectives and a critical contemporary agenda. Bloomsbury Academic.

Gonzatto, R.F. and Van Amstel, F.M.C. (2022), “User oppression in human-computer interaction: a dialectical-existential perspective”, Aslib Journal of Information Management, Vol. 74 No. 5, pp. 758-781. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-08-2021-0233

Grove, S. J., & Fisk, R. P. (1992). The Service Experience as Theater. Advances in consumer research, 19(1).

Shostack, G. L. (1984). Designing Services That Deliver. 1984. Harvard Business Review, 133-139.

Polaine, A. (2013). Service design: From insight to implementation. Rosenfeld Media.

Gibbons, S. Ux vs. service design, August 2021. URL https://www. nngroup. com/articles/ux-vs-service-design

Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space. Massachusetts: Blackwell.

Hewett, T. T., Baecker, R., Card, S., Carey, T., Gasen, J., Mantei, M., … & Verplank, W. (1992). ACM SIGCHI curricula for human-computer interaction. ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2594128

Norman, D. A., & Draper, S. W. (Eds). (1986). User centered system design; new perspectives on human-computer interaction. L. Erlbaum Associates Inc..

Vitor Costa, J. Professora de vôlei deu quatro chibatadas em entregador, em São Conrado. O Globo. April, 04, 2023. https://oglobo.globo.com/rio/noticia/2023/04/professora-de-volei-deu-quatro-chibatadas-em-entregador-em-sao-conrado.ghtml

Franco. L. Mulher é estuprada após ser deixada desacordada na calçada de casa. G1. July, 31, 2023. https://g1.globo.com/mg/minas-gerais/noticia/2023/07/31/suspeito-de-estuprar-mulher-apos-show-de-thiaguinho-em-bh-e-preso.ghtml

Boal, A. (1979). Theatre of the Oppressed; Translated by Charles A And Maria-Odilia Leal McBride. Pluto Press.

Van Amstel, F. M. C., Pelanda, M. F. L, Souza, E. A. B. M. (2020) Design and Precarious Work in Digital Platforms. GFAUD-USP. https://fredvanamstel.com/portfolio/design-and-precarious-work-in-digital-platforms-2021

de Siqueira, I. L. M., & van Amstel, F. M. (2023). Service design as a practice of freedom in collaborative cultural producers. In Proceedings of the Service Design and Innovation Conference (ServDes 2023), Rio de Janeiro. pp. 315-325. https://doi.org/10.3384/ecp203016

Gonzatto, R.F., van Amstel, F.,and Jatobá, P.H. (2021) Redesigning money as a tool for self-management in cultural production, in Leitão, R.M., Men, I., Noel, L-A., Lima, J., Meninato, T. (eds.), Pivot 2021: Dismantling/Reassembling, 22-23 July, Toronto, Canada. https://doi.org/10.21606/pluriversal.2021.0003

Instituto Faber-Ludens. 2012. Design Livre. Clube de Autores. https://designlivre.org/downloadlivro/

Boal, A. (2005). Games for actors and non-actors. Routledge.