So far, design has contributed mostly to domesticate futures for the colonized. Nevertheless, design can also serve decolonizing practices that bring back the contradictory nature of human futures. The domestication of the future is a colonialist strategy that reduces existential time to a desirable space of possibilities that can be designed, packaged, and sold to underdeveloped nations as docile (design) products or as docile (design) services. Monster aesthetics is a reaction to this strategy that sets free domesticated futures by expressing otherness and dissensus. This talk features selected projects from the designing for liberation research program conducted in Brazil.

Video

This keynote talk was recorded at Decolonising Futures in Design Education organized by Elisava and other partners from the FUEL4DESIGN research project.

Audio

Full transcript

It’s really nice to be here, especially with the connection that you draw within our work. I would also like to thank FUEL4DESIGN for creating this opportunity for the Global South Globalization Project—globalization that focuses more on solidarity and not just on making profits.

It’s nice to meet people from all over the world. I see that many people are possibly from the Global South—I can tell by the names—and there are also people from the Global North who are interested in solidarity and in extending the ties between those fighting oppression, mainly colonization. I acknowledge that your presence here is very important, and I hope to represent somehow the position of decolonizing design in Brazil, where I was born into this world and have lived most of my life.

This talk is a compilation of some experiences we have had here in Brazil. As Palak introduced, I’m speaking primarily from a critical perspective on service design and experience design, but you will see different kinds of experiences that apply to other areas of design as well. Let me go back to the historical moment when colonization stabilized this land, which was previously known as Pindorama by its Indigenous natives.

The European colonizers considered the Indigenous people who lived here as savages and tried to domesticate them through catechizing education. This was a highly hierarchical mode of education. As you can see in this azulejo panel, the European figure is positioned at the top, making himself appear as a superior being, donating knowledge to Indigenous people as if these savages had none. You can also see in this panel that the Indigenous people are depicted as emerging from nature like animals, in other words, not fully humans. From the perspective of the Europeans, education meant transforming savages into humans, allowing them to join civilization.

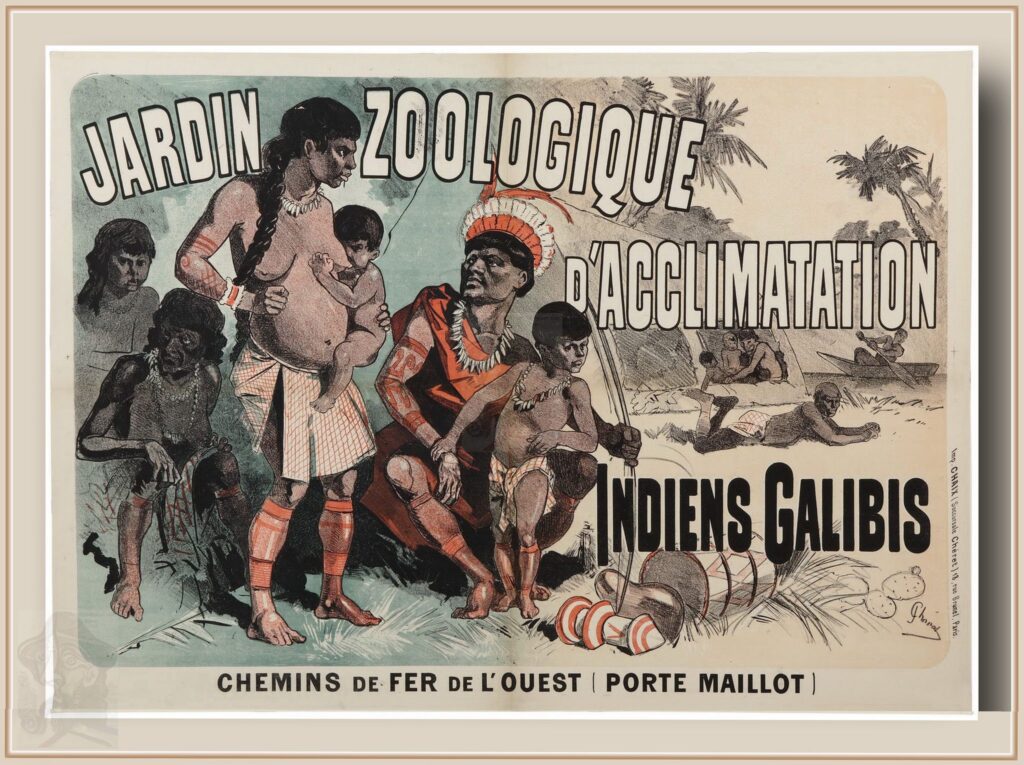

After being domesticated, these Indigenous people—still not considered completely human—were exhibited in world fairs across the Global North, especially in Europe. This image is from the Jardin Zoologique d’Acclimatation, a French zoo with a human section. Human zoos were common at the beginning of the 20th century and remained in operation until as late as 1958—the last documented human zoo was in Belgium in that year.

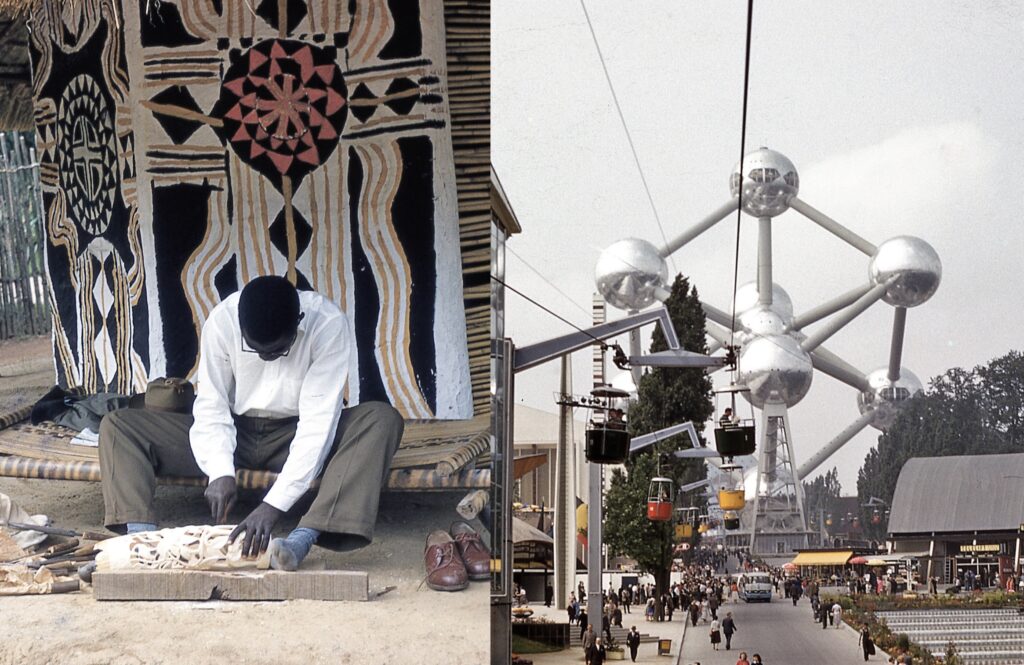

Belgium hosted a world fair called Atomium in 1958. On the right side of this image, you can see the Atomium monument, which celebrated the mastery of nuclear energy. On the left side, you see another attraction from the same fair—an exhibit showcasing Belgium’s so-called achievements in its colonies, particularly in the Congo, which was still under Belgian rule at the time.

This contrast is striking. The domestication of the colonized is the foundation for the domestication of the future. Nuclear energy was developed by exploiting the colonies’ resources, knowledge, and labor. This is all part of history. This contrast between these images is interesting because colonization is bound up with technology. Colonization was justified on the premise that the colonized had inferior techniques and knowledge. This was demonstrated in exhibitions like this one, where the people from Congo who participated were expected to continuously showcase their ancestral techniques for making things.

However, this exhibition did not go as planned. Visitors began feeding the Congolese children similar to how they feed animals in a zoo, disrupting the narrative the organizers intended. As a result, the human zoo section of the exhibition was shut down. However, the colonization of the future is a problem that persists today.

I take the words of Álvaro Vieira Pinto, a very interesting Brazilian philosopher who theorized the colonization of the future. He wrote:

“To the metropolitan technician, the future, being the dimension of the expected time, plays the role of a sounding board, destined to reinforce the current understanding [of reality].” (Vieira Pinto, 2021, p.684)

Thus, the colonization of the future is about ensuring that the future remains the same as the present. This directly relates to design, particularly when representing future visions. Speculative design is an example of this—these design fictions, these marvelous visions of the future, may seem flashy and fashionable while reinforcing the colonization of the future, sometimes unconsciously.

Take, for instance, the Microsoft 2009 vision video scenario. We analyzed this project in a paper published ten years ago, and we dissected how the developing country—in this case, India—is depicted inside a kind of cage, while students from a developed country, Australia, look in. The Australian students are observing through a teleconferencing application—possibly provided by Microsoft—in real time. The Indian students are shown as an exotic attraction, but not as the main subject of interest, since the teacher is also trying to direct the students’ attention elsewhere. This is not an equal cultural exchange.

The advanced technology in the scene belongs to the developed world—Australia and, by extension, the U.S. (where Microsoft is based). Meanwhile, the underdeveloped condition of India, and by implication, other countries in similar positions, is represented as not part of the future. According to this vision, the future belongs to the technologies of the developed countries. We are preparing a paper on how the colonization of the future affects existential time—how people experience and relate to their existence.

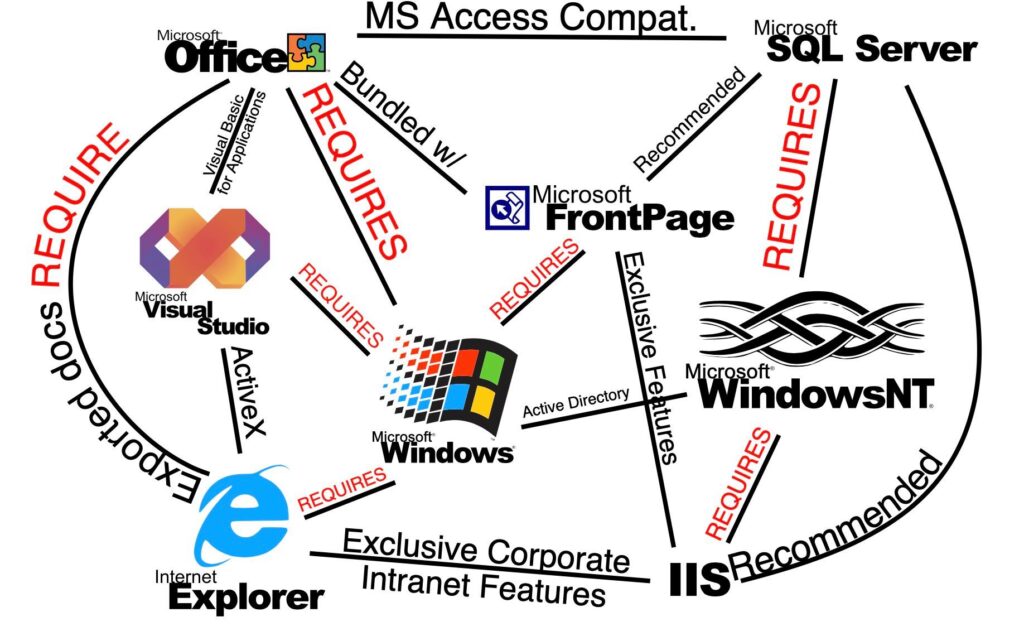

We have written that once domesticated, the future disguises the continuity of the present and oppresses reality. This ideological operation convinces people that the present is fixed and that the future will not bring significant change. This ideology is reflected in technological infrastructures as well. For example, Microsoft’s ecosystem relies on lock-in structures—a network of dependencies that makes it difficult for users to escape. If you use one Microsoft product, you need another, and then another, until you are locked into their system.

The colonization of the future operates similarly: it locks the present to the future, reinforcing the idea that change is impossible. While you are inside this oppressed reality, you don’t have access to other kinds of tools or technologies that could help you develop on your own. You are somehow confused, and people start treating you as if you were underdeveloped because you are using underdeveloped technologies—just like the people from Congo were framed in that exhibition.

Here’s an example: if you use WordArt from Microsoft applications for graphic design, it’s going to look crappy, it’s going to be considered inferior, it’s going to be seen as bad design. The design of the oppressed is considered inferior because the oppressed can only use the technologies that are available within this oppressed reality.

Another crucial turning point for design is how you interact with technology, which makes you feel ugly because your expression and language are treated as wrong. When you try to express yourself or take action using these technologies—these languages—you do not fully understand them because they were not developed in your cultural or geographical context. These are foreign technologies and languages, so you cannot express yourself fully. And then you feel awkward. You may feel like this donkey using a computer.

Paulo Freire (2005), who wrote extensively about oppression and colonization, wrote that “functionally, oppression is domestication. To no longer be prey to its force, one must emerge from it and turn upon it”. Inspired by Paulo Freire and other thinkers in the decolonization movement, we have been developing a Designing for Liberation research program in Brazil for quite some years. I won’t go into the full details of this program, but I will focus on this middle part: the distinction between design practices that produce oppression and those that seek liberation.

We are most concerned with stabilizing partnerships and developing practices that fight oppression and seek liberation. However, we must also change the aesthetic interactions between oppressors and the oppressed. I will refer to the paper that Palak Dudani mentioned while introducing my work. This paper on the Anthropophagic Studio describes how we can devour, digest, and absorb the oppressor’s culture and body, undergoing a process of cultural hybridization that has a long history in Brazil.

For example, Indigenous people in Brazil literally ate the Portuguese—not because they were savages, but because they admired them so much that they wanted them to become part of their tribe, part of their bodies. Being eaten after being captured in war was considered an honor. While we no longer practice literal cannibalism, we do have cultural cannibalism, which continues to this day. We take foreign ideas, relate them to our local specificities, and create something new. This is also how we decolonize design—especially interaction design—by engaging with this process of cultural digestion.

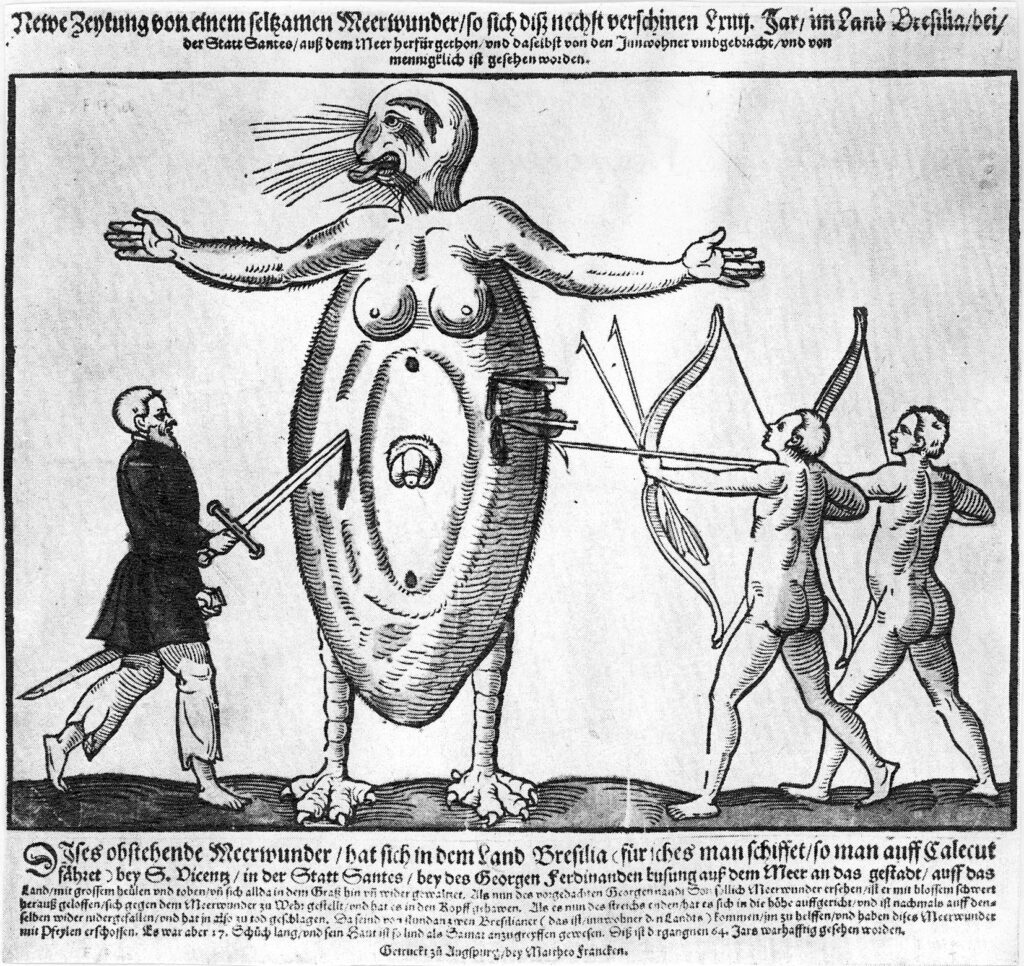

Let me now show you another stream of research that is more closely related to collective body-building—that is, creating an aesthetic feeling that connects people who are considered colonized within this relationship. We started the following project by devouring and digesting the Leviathan. This oppressive collective body tries to remove conflict from society by standing above and representing the presence of the state in everyday life. We also digested the colonizers’ visions of the oppressed collective body. In the early 16th century, European colonizers created all kinds of monsters to explain what they encountered in the colonies. These monsters had features that reflected the colonized bodies they did not understand.

For example, in this image, the Ipupiara is depicted as a mix of a dog’s head, a man’s body, and a woman’s body. This monster is a personification of the hybridization between European and Indigenous cultures. You can see this hybridization in the image’s composition: the Indigenous people are on the right side, the Portuguese colonizers are on the left, and both are fighting the monster together. The beast represents an unwanted otherness, something threatening that must be eliminated.

However, Monster Aesthetics—a concept we are developing in our research—is about the positive affirmation of otherness and collectivity. It challenges colonial standards of beauty and goodness. This work has been developed in collaboration with my fellow student, who wrote a marvelous paper on Monster Aesthetics. The paper is currently in press, and she is also here at this meeting. Thank you for collaborating on this research, Rafaela. When we were doing this research, Rafaela pointed me to previous works in Brazil that explored the collective body from a solidarity and decolonial perspective.

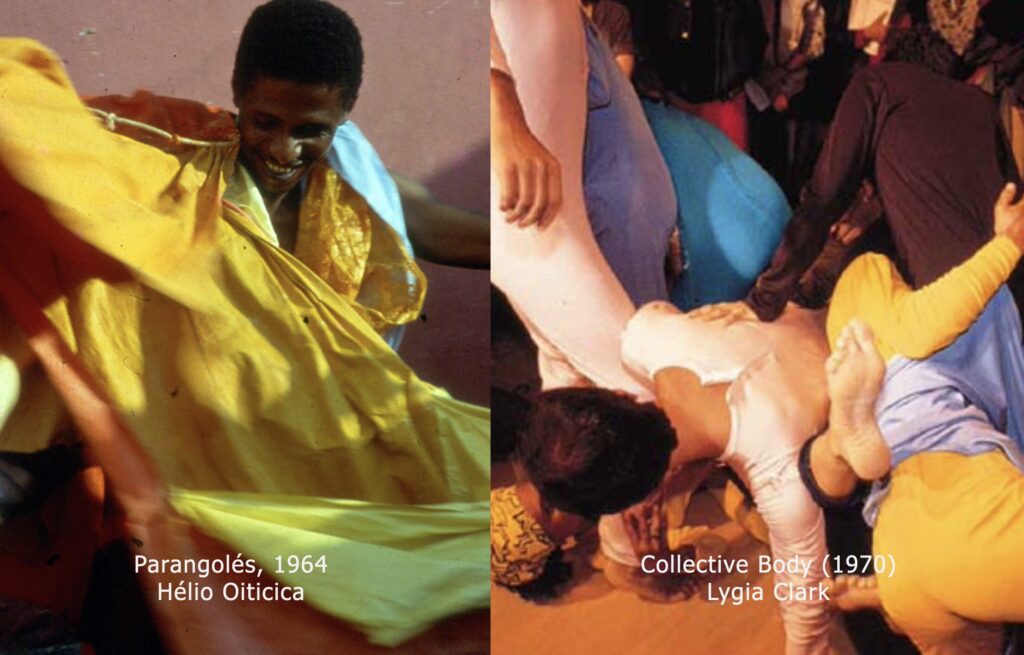

One such work is by Hélio Oiticica, who created an amazing dress designed for participatory performance, the parangolés. As you danced in it, the audience’s participation was required for the artwork to reveal its full beauty. On the right side, you see Lygia Clark’s crazy clothes that were all tied together so that you couldn’t wear them alone—you had to wear them with multiple people. Everyone was connected, and if you wanted to move, it was difficult because everything was tied in a way that, for example, linked hands to feet. To move, you had to engage in a kind of performance, which demonstrated how people are actually connected in many ways—through culture, history, family, and so on.

These ideas were part of the Neo-Concrete movement and, later, Tropicália, both of which sought to emphasize hybridization in Brazil. These movements were heavily influenced by the concept of anthropophagy mentioned earlier.

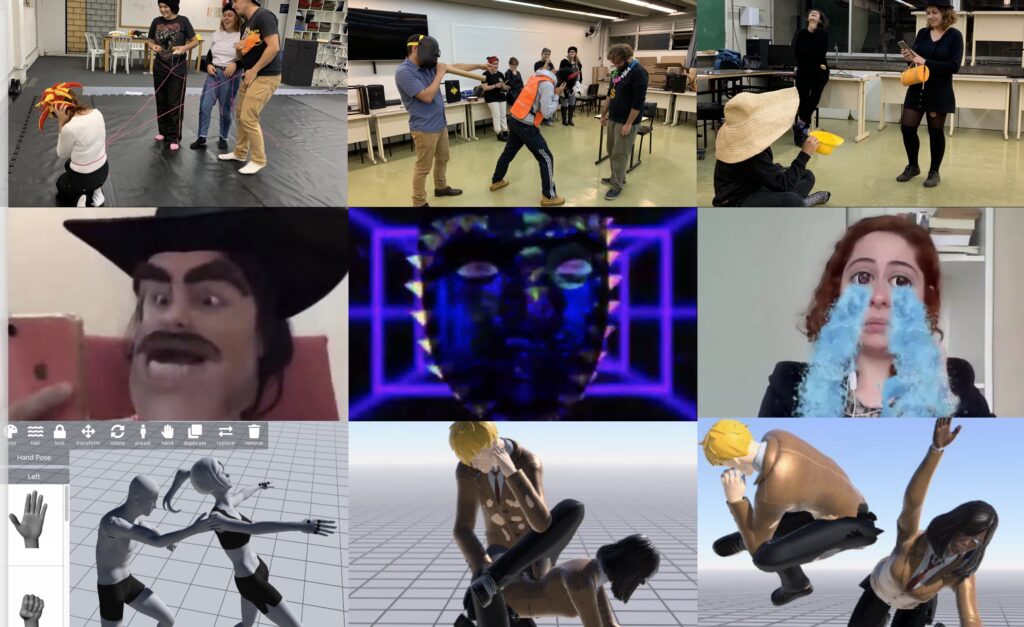

Inspired by these interactive art movements, our students here at UTFPR created a wearable manifesto about what social design is and why social design should be decolonized in Brazil to remain relevant. They also performed in the style of Nildo da Mangueira, a famous performer of parangolés. As you can see in this short video, this generated a sense of otherness and collectivity in the classroom.

The students really wanted to make their voices heard about the way design was being developed—especially in Brazil. They were frustrated to realize that their aesthetic sensibilities had been shaped by colonial standards, particularly by German design education, so they knew nothing about popular design, popular culture, or visual references from their surroundings. Instead, all they knew were German, European, and U.S. references.

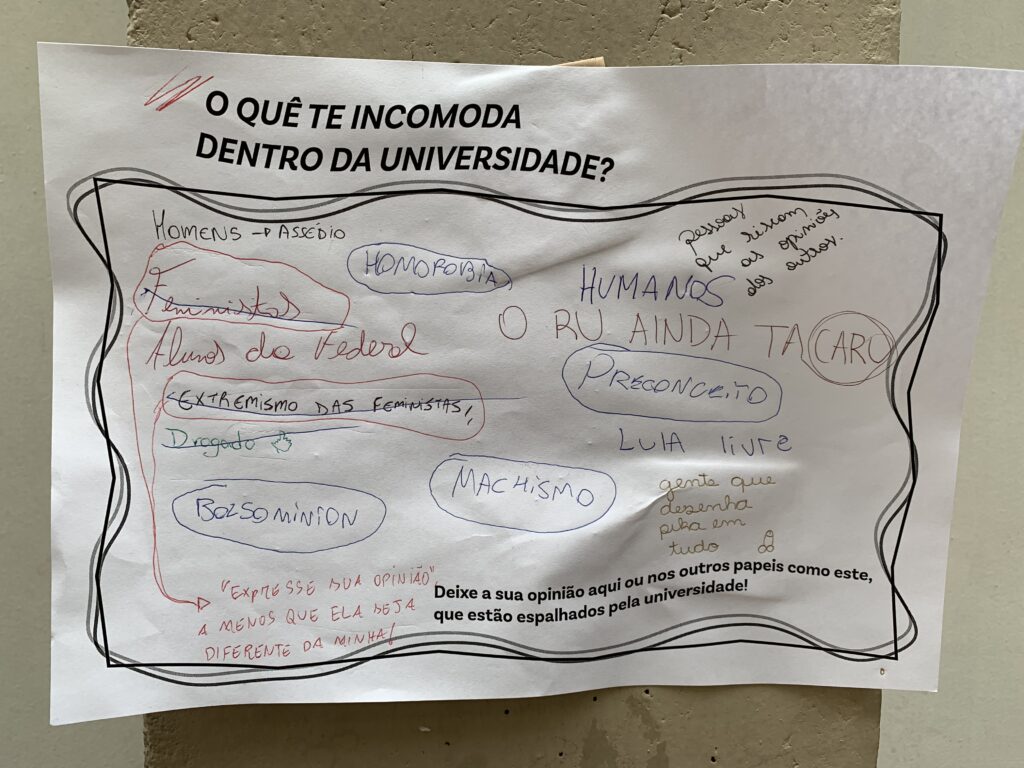

This realization led them to write a manifesto, a digital version of their wearable manifesto, deliberately breaking all the visual norms they had learned from German graphic design. They emphasized dissent while building a collective body where people could maintain their differences. Following this, they decided to take action. They went around the university, posting invitations for conversations.

One of these was a small piece of paper that asked: What bothers you in this university? They were surprised to find that many responses were about sexism or feminism. Of course, as you can see from the strikethroughs and multiple sketches that people added to the paper, there was a dispute over who saw this as a problem and who benefited from the status quo. The students concluded that women were particularly underprivileged in this context and that they needed to intervene.

We discussed many possible interventions at length. Some were too naïve—for example, one idea was to convert all male and female toilets into unisex toilets since female toilets were outnumbered. However, upon further discussion, they realized this would worsen the imbalance since fewer female toilets were already used. Instead, they needed to intervene in the male toilets.

We didn’t get to this step because the course ended, but the process was valuable—it showed the importance of speculating on interventions before implementing them to avoid unintended consequences. So far, all the examples I have demonstrated involve Monster Aesthetics in offline, face-to-face interactions. But now, given the pandemic and the shift to digital interactions, we must ask: how do we awaken monstrous bodies in the face of domesticated, normalized, technocratic, post-pandemic futures?

The Design and Oppression Network was founded in 2020 as a response to social and political isolation. In Brazil, we could not protest on the streets because of the pandemic, so people working in social movements began gathering online. This network has led to many activities that aim to bring our bodies into interactions and create a sense of collectivity without erasing differences.

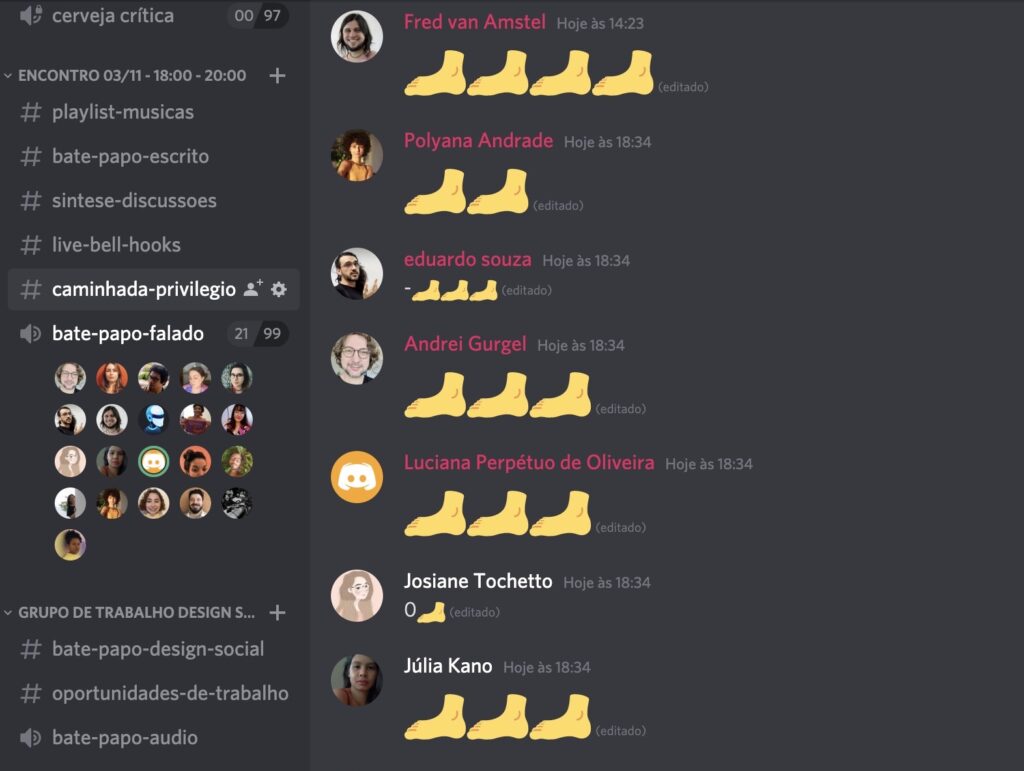

One example was our Design Privilege Walk exercise. Since we were meeting online, we used foot emojis to indicate privilege—those with more privilege displayed more feet. As you can see in this image, I had more feet than many of my colleagues in the network.

Another experiment involved guessing whose hands were whose. Participants posted anonymous pictures of their hands, and we discussed what kinds of work these hands might do. This led to reflections on how bodies are shaped by labor, culture, and identity markers in society. We also experimented with Forum Theater, discussing sensitive themes related to the colonization of Brazilian design and the growing influence of design thinking from the United States—an influence that, in some ways, is replacing the previous dominance of German design.

One particularly fascinating experiment was an augmented reality theater performance called Theater of the Techno-Oppressed, which was incredibly powerful. Afterward, we reflected on how oppression becomes internalized—how we carry it within ourselves. This led us to explore The Rainbow of Desire, a method of collective therapy using theater and avatars to externalize and examine internalized oppression. Finally, we experimented with Image Theater, using 3D modeling to express body postures, body language, and bodily oppression. We compared, discussed, and analyzed how oppression manifests in our physical expressions.

I would like to close with this quote from Augusto Boal (2009), from The Aesthetics of the Oppressed. There he writes:

“We are three-dimensional: we have a personality that is a severe reduction of our person – a cauldron where all human desires, good and bad, qualities and potentialities boil. It is in this bubbling boiler that we get our characters, who, inside ofus, are domesticated or revolted.”

He means that our personality is a severe reduction of our entire personhood. Inside each of us, there is a boiling cauldron of human desires, good and bad qualities, and potentialities. And it is from this bubbling boiler that our characters emerge—some domesticated, some revolted.

The Theater of the Oppressed—and what we are developing in the Design and Oppression Network—is about recognizing that we all have oppressors within us. Even if we are oppressed by others, we are also oppressors in specific ways. Understanding this allows us to engage with the full range of relationships that shape our interactions and undomesticate ourselves.

Last but not least, I have an announcement: We may hold a Design of the Oppressed summer course this year, organized by the Design and Oppression Network. Please stay tuned if you’d like to join us and experiment with undomestication exercises inspired by Theater of the Oppressed, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, and many other Latin American and Brazilian traditions of resisting oppression.

References

Pinto, Á. V. (2021). O Conceito de Tecnologia-volume 2. Contraponto Editora.

Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum, 2005.

Gonzatto, R. F., van Amstel, F. M., Merkle, L. E., & Hartmann, T. (2013). The ideology of the future in design fictions. Digital creativity, 24(1), 36-45.

Van Amstel, Frederick M.C and Gonzatto, Rodrigo Freese. (in press) Existential time and historicity interaction design. Human-Computer Interaction.

Van Amstel, Frederick M.C and Gonzatto, Rodrigo Freese. (2020) The Anthropophagic Studio: Towards a Critical Pedagogy for Interaction Design. Digital Creativity, 31(4), p. 259-283.

Angelon, Rafaela; Van Amstel, Frederick M.C. (in press) Monster aesthetics in a decolonizing design experiment. Art, Design & Communication in Higher Education.

Hobbes, Thomas. Leviathan, 1651.

Camenietzki, C. Z., & Zeron, C. A. D. M. R. (2000). Quem conta um conto aumenta um ponto: o mito do Ipupiara, a natureza Americana e as narrativas da colonização do Brasil. Revista de Indias, 60(218), 111-134.

Angelon, Rafaela; Van Amstel, Frederick M.C. (2020). The political body as a fulcrum for radical imagination in metadesign. In: Proceedings of the III Design Culture Symposium, Unisinos, Porto Alegre, Brasil.

Boal, A. (2009). A estética do oprimido (pp. 1-256). Rio de Janeiro: Garamond.