Abstract: Designing for Liberation is a design research program investigating the possibility of designing for the liberation of historically oppressed people. Instead of designing for privilege like modern design typically has done, we seek designing for rights. Everyone has the right to have good designs, even if that design is a self-built Favela. This lecture introduces this design research program in five dimensions: worldview, historical trajectory, ethical stances, research questions, and aesthetic qualities. It is a historical document of 15+ years of collective design trajectories.

This is a post-recorded lecture from the MXD Spring 2024 Graduate Seminar, University of Florida.

Video

Audio

Full transcript

This is a historical description of a design research program I was part of for almost 15 years. It changed its name and its overall framework, but it focused on the liberation of oppressed people. We didn’t have that idea or conception initially, and I will describe how we got to that point.

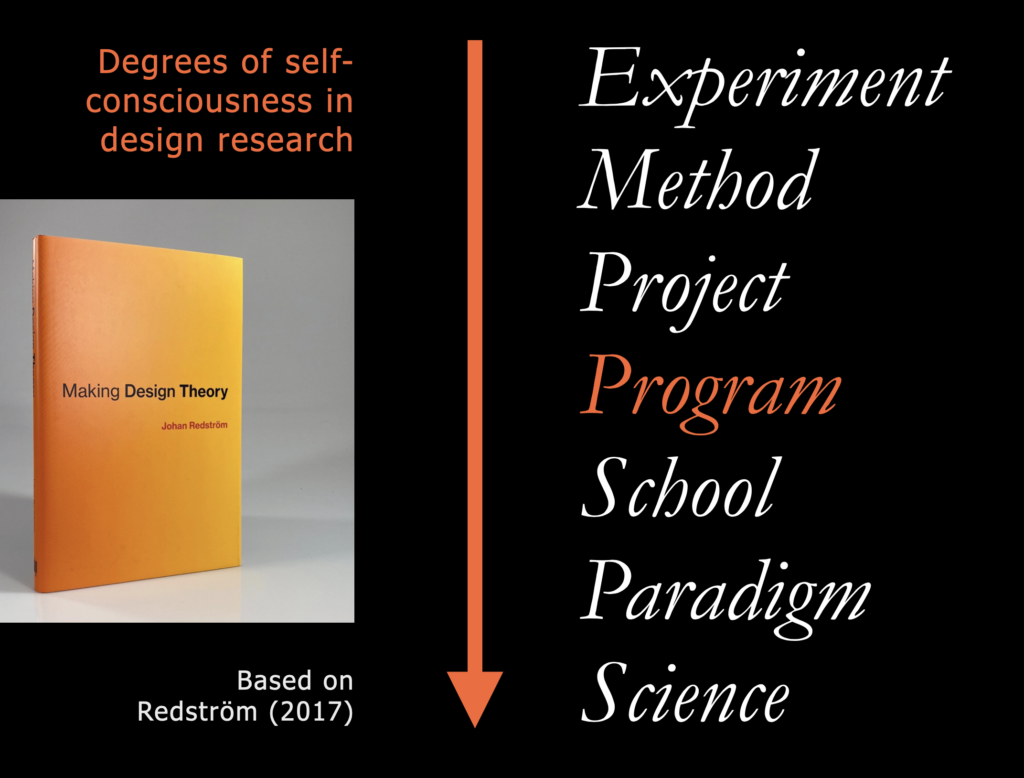

First of all, what is a design research program? I got this definition from the marvelous book written by Johan Redström, Making Design Theory. This book describes several layers or levels of design research organization mechanisms or ways of framing what you’re doing with design research, from the micro-level of an experiment to the macro-level of building a design research science.

I describe this multiplicity of framing opportunities as degrees of self-consciousness. How conscious are researchers about what they are doing regarding the collective accumulative knowledge they are building? If you are only conscious of running experiment after experiment without ever generalizing a method, you have a lower level of self-consciousness. When I say “self” in “self-consciousness,” I mean the collective subject that leads this whole collective experiential activity or knowledge-producing activity, typically involving academia and practitioners in industry settings and social movements.

I’m interested in expanding this level of consciousness, which is part of my research overall. I have another research program, Expansive Design, which sometimes intertwines with Designing for Liberation. The program is mid-level, where you see specific things involving each design situation and generalizing things that manifest across several design situations. So, the program is a kind of intermediate knowledge production site. The kind of knowledge you produce in a design research program is neither something that applies to specific projects nor something as broad as a design school or a school of thought. Instead, a design program is a specific investigation that requires several different projects from several different people and is typically a collective endeavor.

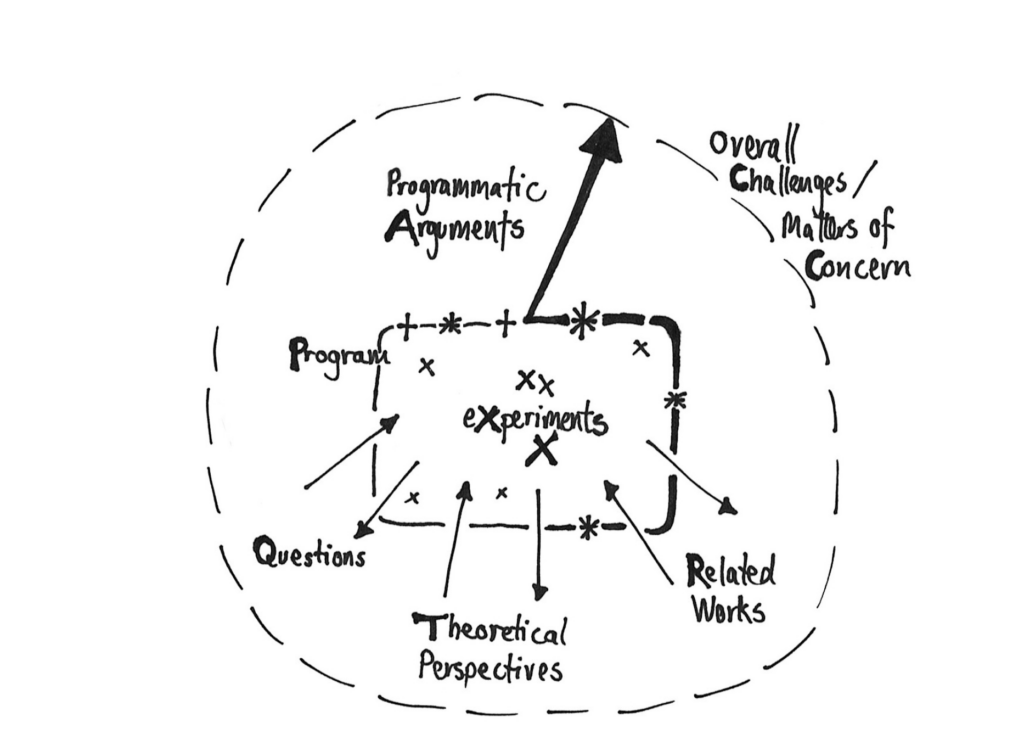

This book by Johan Redström describes how these different levels can articulate and provide challenging opportunities for new design foundations. That’s the whole point of the book, and I like how it frames design research. Well, some other books or articles describe in more detail what a design research experiment is, what a design project is, and what a design school of thought is. I particularly like this article by Bang and Eriksson about the relationship between design programs, research questions, theoretical perspectives, related works, and the overall challenges and matters of concern that society presents to design researchers.

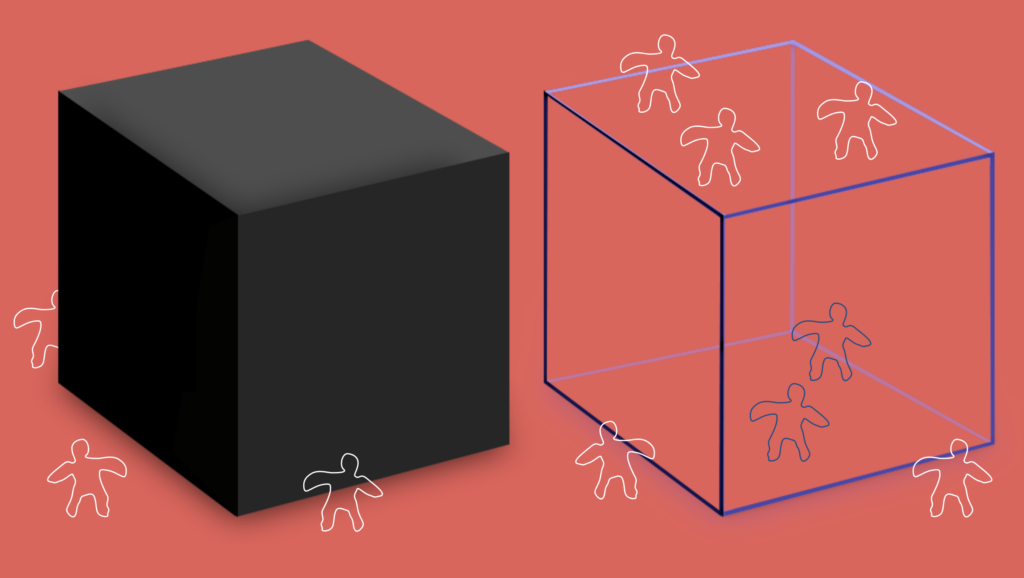

A design research program articulates all these different contextual elements as part of the experimental setting. So, what you can see in this picture, which is very important, is that a design research program—this little box in the middle—is full of different experiments. An experiment is very specific, where you try to intervene or change something in the world and see what you get from it, whereas a program involves several of these investigations, interventions, and experimentations in the world. Every time you experiment, you’re supposed to change the frame of reference for your design research program. So, there’s a dialectical interaction between these two levels of knowledge production. That’s why a program typically develops intermediate-level knowledge.

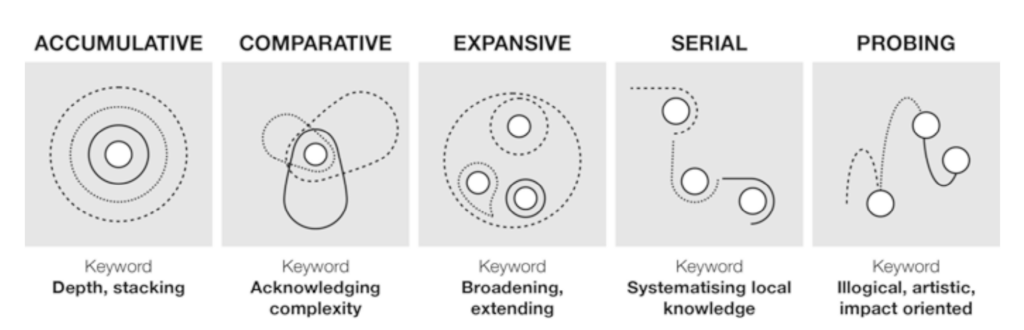

It is interesting to observe how we move from one experiment to another. I’m highlighting here Drifting by Intention book by Krogh and Koskinen. They have written about this movement, describing it as a drifting movement. They rely on this metaphor of speed driving when drivers want to perform a quick shift in the direction of their vehicle but don’t want to lose speed or hit the brakes. So, they turn the wheel in the opposite direction, and instead of changing the vehicle from one side to the other, because the vehicle already has so much inertia in its momentum, the movement twists, and the car drifts away from the ground. It’s a risky maneuver that helps complete a curve at the highest possible speed. This is an interesting metaphor for thinking about how design researchers move from one experiment to another without losing steam or entirely changing the directions or goals of the design research program. It may seem like they are doing something crazy, losing grip and control over the research process, but instead, they are trying to accumulate knowledge differently.

Of course, the cumulative way of building research typically involves starting with a very specific experiment, then the second experiment becomes a little more general, and the third one even more general. That’s how experiments typically accumulate knowledge in other fields, like the social sciences, through generalization strategies. However, we often expand the boundaries of what we believe is possible in design research. This often relies on drifting and serial design experiences, which are pretty interesting. They don’t share the same principles or experimental settings, but you learn from each experiment. My favorite method is probing, where you experiment with something you know very little about, and the connection can only be justified in hindsight after the experiment is complete.

To wrap up this definition of design research experiments: they are pretty much interdisciplinary foundations based on experimental traditions from both science and the arts. When we say we’re doing experimental design research, we mean both rigorous experimental methodologies where you observe conditions for experimenting, take notes on that, and drift through the experiments. However, you also lose control and let the situation reveal more than the experimental design might. Instead of being so strict with defining independent and dependent variables, like in science, design researchers experiment with an open mind, much like artists. The results and outcomes of those different experimental traditions are combined. As the methodology and approach are combined, so are the outcomes. Design research experiments generate data, hypotheses, theories, innovative artifacts, new processes, methods, and new ways of addressing the audience.

That definition is interesting in how these different traditions are merged. Dagmar Steffen provides this great outcome on experiments in the arts and science. However, design research program is something higher-level than a design research experiment. A program is what binds different experiments together.

Based on my readings of the literature mentioned, I list five elements that are very important in defining a design research program. I’m not talking about experiments again to make sure you understand—I’m talking about something that is higher-level and involves several experiments.

- Worldview

- Historical trajectory

- Ethical stances

- Research questions

- Aesthetic qualities

What binds these experiments together is a growing, sometimes tacit, unarticulated, or even culturally bounded worldview. What is a worldview? For example, the modern worldview is that the world is something produced by humans, and humans will produce the world for themselves. That’s the modern worldview, where the world is mostly a material, a medium to change and to produce outcomes. This is very foundational to any design research. Either design researchers adopt that worldview, mostly without acknowledging it, or, for example, the Sciences of the Artificial, written by Herbert Simon, a foundational text in design research, departs from that worldview. But you can also challenge that worldview and question it. For example, decolonial designers try not to be modern or depart from the assumption that the world is passive, not just an object to be transformed but perhaps a person. The world is we. We are worlds, so we cannot change ourselves in a detached way because we are part of the world.

These are two different worldviews, and they clash often in design research. Beyond that, which is more ideological or theoretical, concrete historical trajectories clash with these different worldviews. Multiple waves of design research have been going on for decades, sometimes centuries. These historical trajectories consolidate into some ethical stances. So, how do you typically deal with a dilemma like treating people as material or subjects? Are people objects or subjects of design research? This is a fundamental ethical stance. Some design researchers follow Kantian philosophy, but this doesn’t necessarily translate into their research questions. For example, they depart from the assumption that human beings should never be reduced to objects, but then, in the research questions, they ask, “How can we design a process that will include people as users in this particular setting?” That’s already reducing people to things because a user is never a fully self-defining human. It’s how humans are defined by designers. That is what Gonzatto and I call userism. Here, you can see some contradictions that become clearer once you begin articulating the different levels of the design research program’s foundation.

Last but not least, aesthetic qualities, such as usability in a modernist design research program or relationality in an anti-modern research program. These aesthetic qualities are the kind of effect or the self-indulgent result of the design research sought, and sometimes the ethical stance is embodied and lived throughout the experience of being in a world like that. That’s why I believe an essential connection between ethics and aesthetics exists. But I don’t want to go into too much detail right now; I just want to point out that these five elements articulate each design research program differently. By defining them, you can understand the level of theoretical understanding I’m talking about here.

Let’s apply this provisional framework I devised for analyzing Designing for Liberation, starting with worldview. What is the worldview of Designing for Liberation? I’ve worked on this research program for almost 15 years. Well, I come from an anticolonial scholarship foundation. So I depart from the assumption that Brazil, South America, Latin America, the Caribbean, and the Americas in general share a past of being colonized by European nations. And that past created a geographical, or even ontological, division between a world-that-is-made, Europe, and a world-to-be-made, the Americas. Later on, Europe saw Africa, Oceania, and other places in the world as places they could better “make” than the indigenous people had.

This dichotomic worldview is also the origin of the modern worldview that is foundational to design research. Europe did not recognize the worlds made by Indigenous people, as I mentioned, but actively unmade those worlds. Every civilization that was already installed in America has been destroyed by European colonizers, sometimes through very shady political articulations and other times through confrontation and genocidal wars, which are still ongoing today. In Brazil, for example, in the Amazon rainforest, several indigenous nations are threatened by mining activity. The people supporting those miners are typically companies from Europe or other parts of the so-called civilized world that need these mining materials to produce high technologies and other things that enable modern living.

This connection between the unmaking of those past worlds—what they once called “new worlds” and I prefer to call world-to-be-made—is very much linked to the unmaking of the new or the old world, or what I prefer to call the world-that-is-made, Europe, and other places that colonized and destroyed other civilizations.

You can see, for example, in the picture of the destruction and invasion of what we now call Central America, but at the time, the people who lived there would have called it Abya Yala, Turtle Island, Pindorama, and many other names. These indigenous people who inherited those traditions still call those worlds by such names as a mode of resisting the imposition of concepts like “America,” “New World,” “civilization,” “Western society,” and so on.

This is the basic worldview that I work with, and it is under political attack. It’s probably one of the biggest political debates nowadays in the United States, where I am recording this lecture. There is a political candidate who constantly says that the biggest problem for the United States is the immigrants from Central America, as well as South America and the Caribbean. This person promises that we could Make America Great Again by electing them. What does he mean by great? It was great when this modern civilization, installed by European colonizers, wasn’t challenged by these people. So, as much as we have immigration into the United States, there’s more challenge, Indigenous voices, or at least people willing to challenge and propose new ways of coexisting that aren’t in alignment with the European colonizing mindset.

What is basically behind MAGA is the understanding that some worlds are to be made, worlds that haven’t been made yet. For example, conservation areas, indigenous lands, or even nations in America that need development assistance or a trade relationship with the United States in a leadership position. Of course, the United States is the leader, and all parts of America are being treated as the backyard of the United States. This is what is behind Make America Great Again. It’s an ontological relationship between different worlds where the United States wants to be “the America” because implicit in this motto is the idea that the United States is the only America.

Think about it: all these areas in the American continent are also America. People outside of the U.S. may not feel that electing this candidate would make America as a continent great again. It would only be great for the U.S. So the real motto should have been “MUSGA”—Make the United States Great Again. But by saying “America,” it implies that the United States is the leader of this continent and of the broader concept of a “new world,” which is the American world that should be exported and, through imperialism, imposed on all nations, not just in the Americas, but across all continents. What is now known as the American lifestyle and globalization is spreading differently—globalizing not just life but the nation itself. Anyway, I don’t want to explore that much, but I just want to say that we have developed several different ways of designing from an anti-imperialistic and anti-colonial worldview.

Now, let’s look at the trajectory of this design research program and how it is situated in the history of design research tradition. I’m going back to Brazil’s independence, or the time when the idea of independence was being considered. I’ll bring up an example of the first graphic design product produced in Brazil by the printing press, which the Portuguese king allowed the colony to build only after the Portuguese king had to flee from Napoleon’s invasion of Portugal and install himself and his family in the Brazilian colony. The king then noticed how underdeveloped that area was—there was no printing press, for example—so he commissioned the building of the first one. But instead of producing something useful for the nation or the inhabitants, his priority was to spread ideological values that would make people feel like they were identifying with the king and the queen at court. So the first product was a card deck with royal family members printed on it. That’s already an interesting example of a colonialist graphic design product that marks the beginning of graphic design history in Brazil and the printing press.

Imagine this invention had been around Europe for almost 400 years but wasn’t allowed to be installed in Brazil due to strict colonialist policies that prevented development in the region. That’s precisely the opposite of the theoretical, ideological, or political justification for colonization. That’s why we are against colonization; the practice is often the opposite of what the theory or discourse is about.

Since the independence of Brazil during that same century, we haven’t been able to overcome that condition of dependence on European nations. Sometimes it changed from Portugal to other nations, like in the case of industrial design schools in Brazil. We relied on the Ulm school of design model from Germany, which was very influential. It influenced not just the foundation of ESDI in Rio de Janeiro but also many schools worldwide, especially in underdeveloped countries like India. And this republican, independent Brazilian government still kept importing designs from abroad, much like the colonial government before. Companies followed the same pattern, and this is still going on today.

That’s why we keep talking about the coloniality of making. European design made its way into the world-to-be-made—the former colonies—as the only good design. The ideas of Dieter Rams and several other icons of modern design—that good design is as little design as possible—are inherently colonialist. Think about it: nobody shows the favelas as examples of great modern design, but they strictly follow these principles. They are as little design as possible. They built self-made housing because there was a lack of housing opportunities in the rapidly developing city, like many other Latin American metropolises. These are not bad designs, but unfortunately, they are contrasted with the clean designs of Dieter Rams. There’s a definite contradiction between the form and the function of design.

Think about how much time it takes to get a minimalist design for certain functions and how much time it takes to get a functionalist design out of a simple form as the favelas do; well, the favelas are more efficient. They should even be considered more modern than Dieter Rams’ projects. But anyway, the point I want to make is that Dieter Rams and other modern designers are designing for privilege. The underside of this, the part they conceal with their discourse, is that they also design for oppression. Anytime they design high-profile products that only the rich can afford, that’s designing for privilege and exclusion for those who cannot afford them. Additionally, people who feel uncomfortable, poorer, or less cultured due to their lack of access are excluded.

It’s not just about economic accessibility, which concerns some modern designers. They try to make their designs more affordable, but making a product economically affordable isn’t culturally relevant for the masses. The masses, either through economic or cultural means, are oppressed by modern designs.

Here is an example of a chair designed by Anne Jackson, a Danish designer, in 1959. This egg chair has since become an icon of modern design and has been redesigned and appropriated in several underdeveloped conditions as a kind of aspiration, often bent to serve very oppressive interests, such as treating individuals as the center of society. Here is the former president of Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro, receiving a gift—a Brazilian design-style egg chair. As you can see, the chair’s design hasn’t changed, except for the cover, which is now under the national color scheme. This doesn’t change the fundamental design—it’s still an individualistic and colonialist design that tries to impose the idea of people being enclosed in their worlds. Each person is protected by modern design in their eggs. So, everyone who can afford the chair can stay in their world. That’s one of the principles behind modernist design research programs.

Since we were interested in doing something different, we asked this question: Is it possible to design for freedom instead of oppression? This is the primary research question of the design research program Design for Liberation. To get there, I learned from the work of Jesús Martín-Barbero, a Colombian philosopher of communication, that we need to shift our attention from media to mediations. I translated that in my master’s thesis into a shift from interfaces to interactions—looking at how interaction design is enacted in contextualized situations where people are not just users but also designers, interacting together through these interfaces. The important thing was not the design of the interface but the design of the interactions through the interface. That’s why I claimed that we should also shift our attention from interfaces to interactions, just as communication studies shifted from media to mediations, based on Barbero’s writings.

Inspired by this earlier research as part of my master’s program, I designed several courses, environments, and infrastructures to experience this collective freedom by thinking about social interactions before thinking about objects and things. I cannot avoid talking about one of the most incredible experiences I had with other great people in Brazil when we tried to start a new interaction design institute from scratch. We were utterly self-funded, and from 2007 to 2014, we did so many cool experiments with the cutting-edge technologies of that time, like LEGO Mindstorms, Arduinos, toy hacking, and many other emerging digital materials becoming available for designers in this new field called interaction design.

We always approached these foreign technologies as something to be connected to our Brazilian culture. The concept of interaction was understood in this more relational way, not just as a mechanism that those technologies provided but as something deeply connected to our culture. We were building upon the tradition pioneered by Gilberto Gil, who was the Minister of Culture at that time. He brought this tremendous open-source Creative Commons approach to his ministry, sparking a movement. He was one of the leading figures in what became known as the digital culture movement. He was also one of the first high-profile artists to record and share a full album under Creative Commons as an example of what other artists could do with their work. Many artists have built upon what Gilberto Gil started, and he kept inspiring people even after stepping down from office.

At Faber-Ludens, we continued investigating how we could do interaction design as part of this emerging digital culture in Brazil. Around 2010, we arrived at the concept of design being a kind of black box that needed to be opened. At some point, we realized we had to make it transparent so that people could see inside the box, and if they wanted, they could get in and change it from within. This stood in contrast to the colonialist or imperialist view of Apple design, which was quite influential at the time in what is now called user experience design, but back then was still known as interaction design. We tried to create an alternative based on free software—not just open source. We were in tune with the more politically oriented approach to digital technology, championed by figures like Richard Stallman and others in Brazil, who advocated for relevance to our digital culture movement.

In 2012, we wrote a book reflecting on what we were trying to do and the future of design. It’s called Design Livre, and a Spanish translation by a collective in El Salvador called Diseño Libre. We currently don’t have an English translation. In this book, we argued that design could be as profound and as people-focused as free software was—and still is in many places worldwide. Underdeveloped communities can only access the internet and produce value if they rely on free software because proprietary software always depends on multinational and digital colonialist enterprises. For example, the Google Drive suite—we couldn’t do Design Livre using the Google Drive suite. We tried, but it didn’t work because it was very hard for the general public to participate in those projects. It was challenging to remain open to the public, so instead, we designed our own platform, Corais.

We built it from scratch using free software frameworks like Drupal and Open Atrium. As we designed in public using the same platform as a metadesign project, many other collectives beyond Faber-Ludens joined us. We were surprised by how many digital culture entrepreneurs and cultural producers started using our platform to redesign their economies. We then joined forces and began participatorily designing of the platform with these emerging collectives. We came up with a great innovation called the social currency feature. It was striking—so many, even hundreds, of different collectives built on this tool, managing entire solidarity economies based on this system. Solidarity economies are based on self-management, where the work people do is not framed as volunteer work toward a collective in some vague way but as an economic transaction under solidarity terms. They use their own currency to formalize this economy and build collective self-consciousness.

You could see on the dashboard that an economy had been established for a specific collective at a certain point because most participants maintained a positive balance. So, as you can see, not many people were in debt, which is a good sign for an economy—at least from a solidarity perspective. Unfortunately, in capitalism, there’s this strange system where many people (including big nations) being in debt is seen as a good sign. That’s why capitalism is always heading toward crises. But I don’t want to divert from the main topic.

What we wanted to do was keep defining the characteristics of this design research program. At some point, we came up with a research question even broader than we had initially thought because we were dealing with fundamental aspects of our society. This question was: What is the difference between freedom and liberation? This question arose, in part, from our engagement with the English language. When we started to write and talk about our research in English, we realized that the words “livre” and “libertação” in Portuguese didn’t precisely match with “freedom” and “liberation” in English. We grappled with these four words and concluded that we needed to make a distinction.

We were also influenced by new collectives organizing and occupying platforms like Corais. These were social movements, indigenous communities, and popular educators with agendas different from ours at Faber-Ludens. Of course, we were fighting digital colonialism from the ground up, but these other collectives were fighting against racism, the genocide of Indigenous cultures, and the loss of languages and traditions that were considered pre-modern or outdated. This amounted to around 700 projects. After deeply engaging with these collectives, even visiting them occasionally, we changed how we approached Designing for Liberation. At first, we discussed designing for freedom, but we shifted to designing for liberation. We then started to design experiences and services to strengthen these social movements’ liberation efforts.

Social movements talk about liberation because they believe freedom is not guaranteed by the current society. We have to work to produce this collective freedom, and that’s what liberation means. The Workers’ Party in Brazil (PT), closely connected to several social movements (particularly the workers’ movement), had the idea of deepening participatory democracy using digital tools. I was called to participate in this project in 2015, and we redesigned a platform called Dialoga Brasil, which was an opportunity for 200,000 people to participate by giving critical feedback on governmental programs. Of course, this initiative was interrupted by the coup that removed Dilma Rousseff from office in 2016. Unfortunately, this entire attempt to build a participatory design culture across Brazil in the government was abandoned, and subsequent governments haven’t picked it up.

I shared this experience with my students when I started teaching in 2015, and they were very concerned about the country’s future, as we were in the midst of the most significant political crisis in 30 years. They were interested in what design, specifically interaction design, could do about it. We experimented with many different formats, but the speculative mockumentary—a fake, futuristic, and retrospective exploration of what happened, changing the course of history, and being counterfactual yet also prospective about what could have been done differently—generated some very interesting reworkings of our histories. It was as if we could be better and more than we were in that current present. So we started experimenting with alternative presents instead of discussing alternative futures, taking a contrasting and even anti-colonial approach to speculative design.

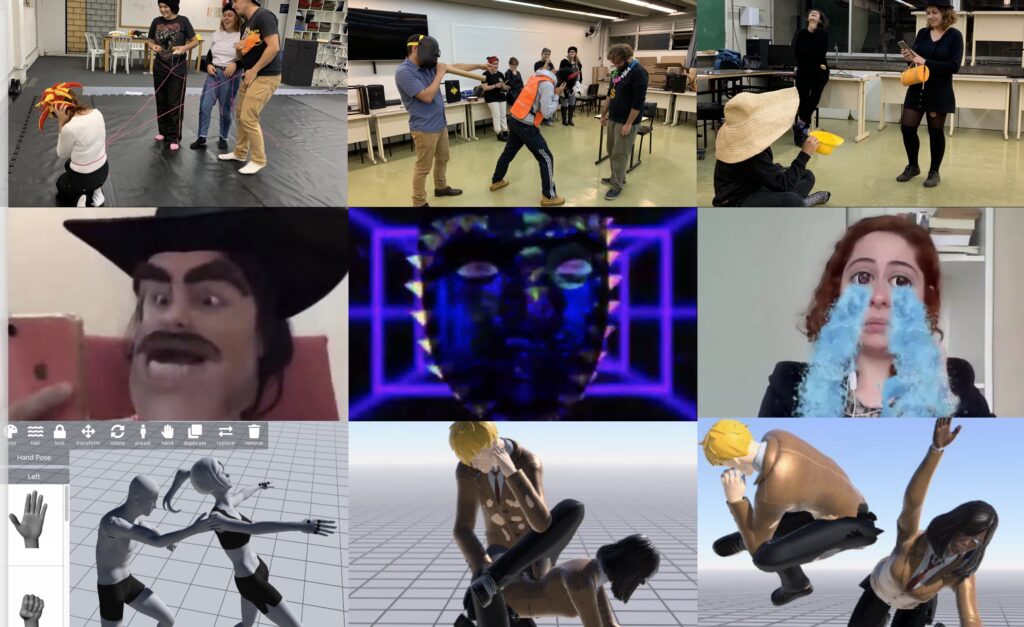

Theater of the Oppressed was one of the main methodological approaches we used to create these speculative mockumentaries. Before we wrote scripts, we explored the design space of oppression and liberation using our bodies and played out the scenarios, usually with different props, figurines, and costumes. We wanted to help students embody those positions of being either an oppressor or the oppressed and switch between these positions to see each other’s perspective and how reality was completely shaped by that relationship.

Later on, we evolved this process of doing Theater of the Oppressed into what is now known as Theater of the Technopressed, focusing on technologies as a medium for oppression, amplifying oppression in this digitally structured society. It becomes part of the infrastructure of society. On the image’s top corner, you can see our experiments done at the Federal University of Technology, Paraná, where we tried to understand, for example, how digital technologies like social media stimulate people to become more egocentric while simultaneously exploiting each other’s social capital.

At the bottom, in the middle, you see some experiments with doing Theater of the Technopressed online, remotely, and improvised because of the pandemic in 2020. We were trying to grasp digital ways of being embodied while maintaining the relationship between oppressors and oppressed in various settings, evaluating not just the traditional class relationship between workers and their bosses but also gender relationships between women and men, racial relationships between white and Black people, and international relationships between the Global North and the Global South.

We put all of this into practice throughout our Design for Liberation program. Back at the University of Technology, Paraná, we tried to build an ideology for this emerging way of designing by the oppressed, for the oppressed. We wrote a manifesto that combined different perspectives of the students, who were primarily women. We came up with the concept of monster aesthetics to explain the kind of expression we sought after writing this manifesto. After it was completed, we had this ritual of collectively embracing it. We then experimented with translating the aesthetics into graphic design. We wrote another, more detailed version of this manifesto using Google Drive to appropriate and subvert its biases toward collective design. Since nobody can control or gatekeep the graphic design, everyone can always change it. We ended up with this very busy manifesto that challenged all the colonialist and modern graphic design rules that our students had learned. They wanted to emphasize that we should be critical about reproducing those patterns rather than merely putting them forth in their work.

Finally, we arrived at a guiding research question that helped us drill down into what oppression, liberation, and what design can do about it. By 2020, we had built partnerships and projects from the Design and Oppression Network. It started with an online reading group during the pandemic, relating Paulo Freire to design research. Later, we included thinkers like Frantz Fanon, Augusto Boal, bell hooks, and others who wrote about oppression. We devised a systematic way of understanding oppression and liberation, which is still pending publication. More on that in the future.

The Design and Oppression Network mostly gave us a pedagogical approach to scaling up these ideas. At the Federal University of Technology, Paraná, we had the opportunity to establish a new laboratory called LADO (Laboratory of Design Against Oppression). I worked closely with Marco Mazzarotto, Claudia Bordin, Fernanda Botter, and several students. Hundreds of students have participated in our activities, experimenting with and confronting various forms of oppression, not just class, gender, and race, but also what we identified as user oppression. This was a significant discovery. We realized that whenever someone is called a user, they are being oppressed. We sought to design not for a user but as a user, looking at the world as a design against us. This represents an entirely different way of learning how to design, which we pioneered in this laboratory.

We shared these findings and collaborated with other laboratories in the Design & Oppression network through the Designs of the Oppressed online course. We have held two editions, and all the materials are available online as open educational resources. We had participants from many worlds experimenting with different approaches to design. As the network grew, we published a call for papers in the Diseña Journal, a Chilean journal that defies academic standards by publishing special issues that are consistently subversive and counter to the modernist canon. With Leslie-Ann Noel and Rodrigo Gonzatto, I guest-edited two issues containing dozens of articles introducing methodologies, theories, and approaches to design from the Global South and the oppressed.

Design for Liberation has evolved into an experimental design research program characterized by crafting certain aesthetic qualities. This brings us to the final aspect of what a design research program entails, and it’s perhaps the highest level of abstraction. We reviewed the history of the Design & Oppression network over the last three years and identified six aesthetic qualities that were prioritized in all the projects we worked on: freedom, criticality, solidarity, autonomy, dialogicity, and monstrosity. Design for Liberation projects typically produce each of these qualities, manifesting both graphically and temporally. These are visual principles and describe temporal aesthetics, particularly the relational aesthetics seen when people dance together.

We rely on this metaphor, or perhaps the practice, of dancing together in the ciranda, a traditional dance from Pernambuco. The ciranda became an organizing principle for LADO. Each working group operated like a ciranda, with rotating tasks to avoid the emergence of leadership and prevent anyone from becoming an oppressor. Building on this metaphor of the ciranda, Marco Mazzarotto, my colleague from LADO, and Bibiana Serpa, from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, wrote an incredible paper for the Design Research Society Conference in Boston. It outlines a militant design research methodology for Design Against Oppression, visually represented as a flower but grounded in the relational qualities of dancing together.

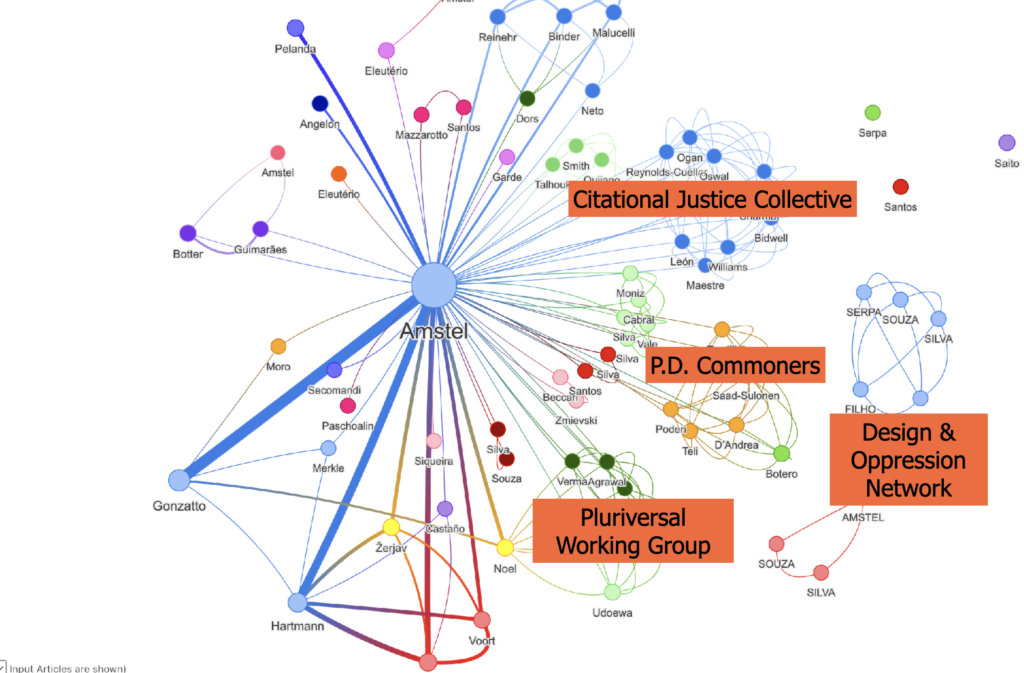

Several design researchers from beyond the network have contributed to Designing for Liberation. This picture shows my co-authorship network. On the right side, you can see my co-authors from the Design & Oppression Network, who are crucial to this research program, as well as collaborators from outside Brazil, such as those in the PD Commoners Network, which focuses on liberating ourselves from capitalist society, and the Citational Justice Collective, which is concerned with epistemic injustice, part of the colonialist framework. The Pluriversal Working Group includes people from several worlds within this world, addressing different systems of oppression.

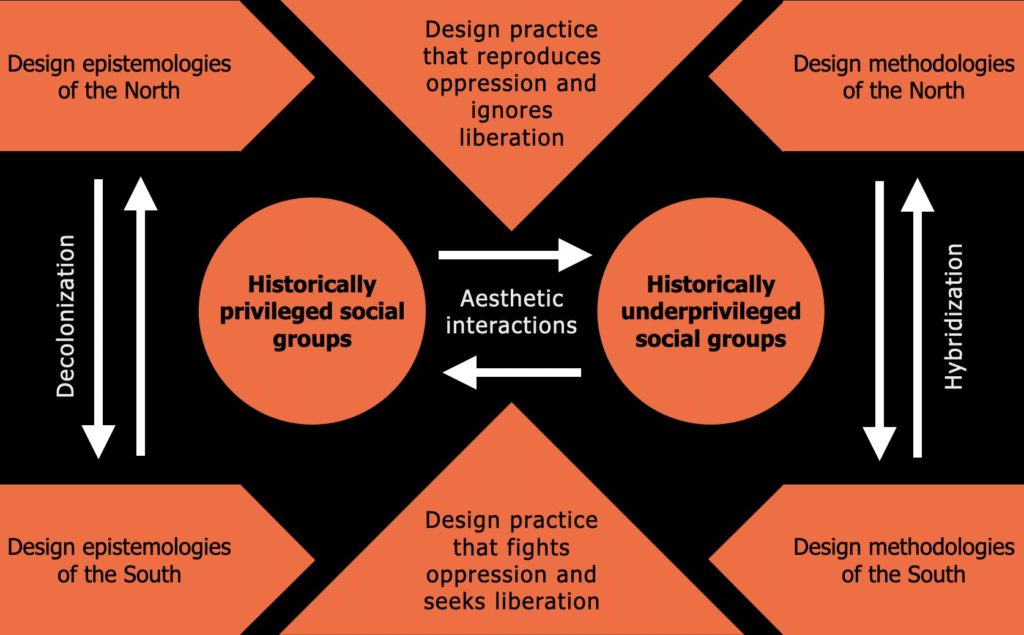

Our design research program is based on a dichotomic worldview. This was not something we defined but something imposed on us as people who have experienced oppression. We know that our world is different from the world of the oppressors and the privileged. The difference is not merely cultural but ontological, profoundly shaping our reality experience.

In conclusion, we aim to create aesthetic interactions where the privileged work with the underprivileged in conflict, but a conflict that produces a new relationship between these different groups, potentially transforming oppressive structures and ushering in a liberated society. By that, I mean liberation from all forms of oppression: class, colonialist, gender, transphobic, homophobic, and many others. These systems keep the historically underprivileged from becoming what they could be and hinder humanity’s cultural evolution.

We are working on a new set of experiments in the MXD program at the University of Florida, my new academic environment. I cannot share much yet, as we are still figuring out what will work in this Design for Liberation research program. Stay tuned for future publications and lectures. The references for this lecture are available online, so you can check them later. Thank you very much for watching, and please share this with someone you think might be interested in these issues.

References

Redstrom, J. (2017). Making design theory. MIT Press.

Bang, A. L., & Eriksen, M. A. (2014). Experiments all the way in programmatic design research. Artifact: Journal of Design Practice, 3(2), 4-1.

Höök, K., & Löwgren, J. (2012). Strong concepts: Intermediate-level knowledge in interaction design research. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI), 19(3), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1145/2362364.2362371

Cai, P., Mei, X., Tai, L., Sun, Y., & Liu, M. (2020). High-speed autonomous drifting with deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters, 5(2), 1247-1254.

Krogh, P. G., Koskinen, I., Krogh, P. G., & Koskinen, I. (2020). Ways of drifting in design experiments. Drifting by intention: Four epistemic traditions from within constructive design research. Springer. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-37896-7

Steffen, D. (2014). New experimentalism in design research: Characteristics and interferences of experiments in science, the arts, and in design research. Artifact: Journal of Design Practice, 3(2), 1-1. https://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/artifact/article/view/3974

Simon, H. (1996). The Sciences of the Artificial, 3rd Edition. MIT Press Books.

Gonzatto, R.F. and Van Amstel, F.M.C. (2022), “User oppression in human-computer interaction: a dialectical-existential perspective”, Aslib Journal of Information Management, Vol. 74 No. 5, pp. 758-781. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-08-2021-0233

Van Amstel, F. M. C. (2023). Decolonizing design research. In: Rodgers, Paul A. and Yee, Joyce (Eds). The Routledge Companion to Design Research (pp. 64-74). Routledge. https://www.doi.org/10.4324/9781003182443-7

Van Amstel, F. M. (2008). Das interfaces às interações: design participativo do portal broffice.org. Thesis (Master in Technology). Federal University of Technology Paraná, Curitiba, Brazil.

Amstel, Frederick M.C. van; Vassão, Caio A.; Ferraz, Gonçalo B. 2012. Design Livre: Cannibalistic Interaction Design. In: Innovation in Design Education: Proceedings of the Third International Forum of Design as a Process, Turin, Italy. https://fredvanamstel.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/Cannibalistic_IxD_Innovation_in_Design_Education.pdf

Van Amstel, F. M., & Gonzatto, R. F. (2016). Design Livre: designing locally, cannibalizing globally. XRDS: Crossroads, The ACM Magazine for Students, 22(4), 46-50. https://doi.org/10.1145/2930871

Gonzatto, R.F., van Amstel, F.,and Jatobá, P.H. (2021) Redesigning money as a tool for self-management in cultural production, in Leitão, R.M., Men, I., Noel, L-A., Lima, J., Meninato, T. (eds.), Pivot 2021: Dismantling/Reassembling, 22-23 July, Toronto, Canada. https://doi.org/10.21606/pluriversal.2021.0003

Van Amstel, Frederick M. C. and Gonzatto, Rodrigo Freese. (2022). Existential time and historicity in interaction design. Human-Computer Interaction, 37(1), pp.29-68. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/07370024.2021.1912607

Angelon, Rafaela and Van Amstel, Frederick M.C. (2021) Monster aesthetics as an expression of decolonizing the design body. Art, Design & Communication in Higher Education, 20(1), pp. 83-102(20). https://doi.org/10.1386/adch_00031_1

Angelon, Rafaela; Van Amstel, Frederick M.C. (2020). The political body as a fulcrum for radical imagination in metadesign. In: Proceedings of the III Design Culture Symposium, Unisinos, Porto Alegre, Brasil. https://fredvanamstel.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/The-political-body-as-a-fulcrum-for-radical-imagination-in-metadesign.pdf

Mazzarotto. M., Van Amstel. F. M. C., Serpa, B. O., Silva, S. B. (2023). Prospecting anti-colonial qualities in Design Education. V!RUS Journal, 26, 135-143. Translated from Portuguese by Giovana Blitzkow Scucato dos Santos. Available at: http://vnomads.eastus.cloudapp.azure.com/ojs/index.php/virus/article/view/833

Serpa, B., and Mazzarotto, M. (2024) Towards a design methodology against oppression, in Gray, C., Ciliotta Chehade, E., Hekkert, P., Forlano, L., Ciuccarelli, P., Lloyd, P. (eds.), DRS2024: Boston, 23–28 June, Boston, USA. https://doi.org/10.21606/drs.2024.617a