Abstract: Most design theories and design methods are crafted to support the current hegemonies in society. While trying to sustain these hegemonies, designers eventually realize they are unsustainable, unfair, or dehumanizing. Among them, designers who develop a bit of critical consciousness rightly feel the need to shift from designing for to designing against hegemonies. More often than not, they immediately lose critical consciousness by countering hegemony through naiveté: by rejecting design theories and methods entirely. Unequipped, designing against staying at the safe side of speculating reactions without taking consequential measures. Guided by the Latin American tradition of critical thinking, the Laboratory of Design against Oppression (LADO) at UTFPR does not reject design theories and methods but redefines their purposes. In this lab, the decolonization of design epistemologies goes hand in hand with the hybridization of design methodologies. In this talk, selected projects from LADO and from the Design & Oppression network will be displayed to illustrate this point.

This talk is part of Collective Praxis as Designing Radicality seminar hosted by the Counter-Framing Design project.

Video

Audio

Full transcript

Let me start by complementing some special information about my background. I’ve been involved in many different knowledge areas and communities across various countries, making it difficult to define my specific standpoint—where exactly I am speaking from. But I would say that in Brazil, I am a white cis man from a working-class family. I’ve been trying to use the privileges I have to design against oppression. At the same time, I also design for a set of values that I deeply believe in—values I strive for and dedicate my life to.

In this talk, I’ll reflect on different moments in my life where I was designing for something more willingly than I was designing against something. This will be a short talk, and I hope you can join me later for a discussion with Sharon.

The starting point is the concept of hegemony. What is it?

We could spend a lot of time discussing this, but I’ll briefly explain how I understand hegemony in Marxist theory. There is a dialectic between the superstructure—the ideological and organizational aspects of society that set directions, exploit, and distribute wealth—and the infrastructure—the working class, the factories, and the material conditions of society.

This dialectic is discussed by Gramsci and other Marxist authors. In Latin America, for example, scholars explore how hegemony is the process by which the superstructure attempts to dominate the infrastructure, while the infrastructure also attempts to influence the superstructure. This struggle to control reality is what we call hegemony.

If this brief summary feels too abstract, let me give you a concrete example of how I learned what hegemony is—by playing Civilization III. In this game, a major change from Civilization II was that you could dominate other civilizations without entering into war. If you built a highly advanced society—with cutting-edge technology, arts, and culture—neighboring cities with their own cultures would, over time, abandon their own governments and request to join your civilization.

That’s precisely what’s happening in this screenshot: the military advisor informs us that the loyal citizens of another land have overthrown their oppressors and pledged allegiance to us. This city was not originally part of our empire. But over time, it wanted to be integrated—by its own decision. And that is hegemony. It is when the oppressed act in favor of the oppressors because they have come to believe that the oppressors’ superstructure is superior to their own.

Oppression is reinforced from both sides. The oppressed accept domination in the long term, while the oppressors make strategic short-term concessions, appearing merciful to secure their control in the long run.

On this slide, you can see how different forms of oppression reinforce one another. This is a point often overlooked in Gramscian studies of hegemony. Black feminist and intersectional studies highlight how colonialism, white supremacy, and capitalism mutually reinforce each other. These systems interlock in ways that make it difficult to trace where oppression begins. This entanglement can itself be seen as part of hegemony—because it binds infrastructure and superstructure so tightly that many people accept these conditions as natural.

For example, this is why we normalize ecocide—the destruction of the planet. Human supremacy over nature has been ingrained into our culture, making it feel inevitable. But this is not an inevitable condition. Dr. Rupa Marya created this map to show that oppression cannot be fought one piece at a time—all forms of oppression must be challenged together.

So, my question is: to what extent does design research contribute to oppressive hegemonies? And more importantly: how can design research work against hegemony instead of reinforcing it?

To explore this, let’s do a simple Google Scholar search for design research using two keyword phrases: designing for and designing against. Google’s search suggestion algorithm, which reflects common research interests, reveals something striking.

When we look at “designing for,” the top results include:

- Designing for situation awareness

- Designing for children

- Designing for behavior change

- Designing for the digital age

These are all examples of research that supports existing hegemonies.

Now, let’s look at “designing against.” You might expect it to mean designing against hegemonic structures. But instead, it mostly consists of:

- Designing against crime

- Designing against vandalism

- Designing against bicycle theft

These examples protect the existing social order rather than challenging it. The focus is not on counter-hegemonic actions but on reinforcing the status quo. And the most striking evidence of this imbalance? The total number of results:

- Designing for yields over 500,000 research articles.

- Designing against? Barely 5,000.

The question is: is design inherently hegemonic? Can we even conceive of a way to design against hegemony?

In my PhD research, I examined how design spaces are constrained by socially constructed taboos. These constraints have historical origins in contradictions such as oppression. If we only engage in “designing for,” we remain within the bounds of hegemonic design spaces. We fail to imagine alternative ways of being human or structuring society.

Many of these alternatives are dismissed as impossible—not because they truly are, but because we are conditioned not to think about them. Counter-hegemonic design research operates at the boundaries of what is considered possible and acceptable versus impossible and unacceptable. It pushes against these limits, expanding our collective imagination.

Now, I’d like to present some experiments in designing for liberation. In 2007, I co-founded the Faber-Ludens Interaction Design Institute in Brazil. We published a paper about that, which became the institute’s guiding philosophy. We metaphorically digested foreign technologies and reinterpreted them through our local culture.

In 2011, we created a platform to open-source this approach—extending it beyond interaction design to other fields. This is Corais platform, which, even ten years later, remains active with over 700 collaborative projects. Corais primarily serves the digital culture movement in Brazil. Many users are people seeking to preserve and update traditional popular culture. The platform helps them sustain their livelihoods despite government cuts to cultural funding—especially those affecting grassroots traditions.

We’ve produced many collaborative books and other materials. But reflecting on this experience, I now see a major shortcoming: At the time, we spoke about freedom—free software, free design—but we had no clear concept of liberation. Only after revisiting our work through the lens of oppression studies did we realize: we weren’t just fighting for freedom—we were fighting against oppression.

In 2020, together with others, we co-founded another institution called Design & Oppression. We have been very active in organizing study groups, developing online educational resources, and publishing academic papers on design and oppression—examining the historical relations that are often overlooked in design research and theory.

As part of this effort, the Design and Oppression Network also organizes a series of Theater of the Techno-Oppressed online sessions. For instance, we presented a theater play titled Wicked Problems, Wicked Designs at the Attending to Futures conference in Germany. In this play, we used the language of theater to scrutinize and critique dominant design thinking discourse—particularly the notion that any problem society fails to solve should simply be framed as a wicked problem, one that can be tamed but never fully solved.

This framing allows design thinking to sidestep major ethical dilemmas. If a solution is never final, only provisional, then there is no ultimate accountability. Our play exposed how this discourse perpetuates oppression within design thinking by obscuring its role in reinforcing sexism, colonialism, and racism. You can watch the recording of this play on my website. I believe it offers an interesting way to integrate artistic methods into discussions about design.

At my university, we have also been exploring these themes in an academic setting. This year, we founded the Laboratory of Design Against Oppression (LADO). LADO is a self-organized—or perhaps better described as a self-managed—laboratory where students take the initiative. They collaborate with others who share their interest in conducting counter-hegemonic design experiments. We organize ourselves using a Discord server, where we form working groups to carry out various projects. Some of our experiments include:

- Redesigning a village town hall to better reflect community needs

- Prototyping housing solutions for marginalized communities

- Designing a publishing press for the oppressed, ensuring that people who are excluded from mainstream publishing—due to race, class, or ideology—can have their voices heard through books, poetry, and other publications

This last project aims to empower authors who might never be accepted in the commercial book market.

One of LADO’s most important experiments took place in 2019: the Wearable Manifesto. In this experiment, students wrote messages on pieces of cloth—statements about what they wanted to change in society through design. Each student approached the project differently, with their own utopian visions. They then sewed these pieces of cloth together, creating a collective garment. Some of the ideas contradicted each other, yet they wore it anyway. Their reasoning was that democracy is not about consensus but rather about dissensus, as argued by Jacques Rancière.

The experiment reflected the aesthetics of democratic disagreement—embracing difference rather than erasing it. Later, we analyzed the aesthetics that emerged from this experience. We identified it with monstrous expressions of otherness, a theme deeply explored in postcolonial studies. Through this aesthetic, we rejected the idea that liberation requires becoming equal to the oppressors or assimilating into the dominant system. Instead, we embraced a radical strangeness—an opposition to the modernity project itself. We even created a digital version of the manifesto, intentionally breaking all the graphic design rules we knew—further reinforcing this idea of rejecting imposed norms.

Through these different experiments, we have realized the need to decolonize and hybridize design knowledge. This means incorporating perspectives from multiple origins rather than relying solely on dominant Western design traditions.

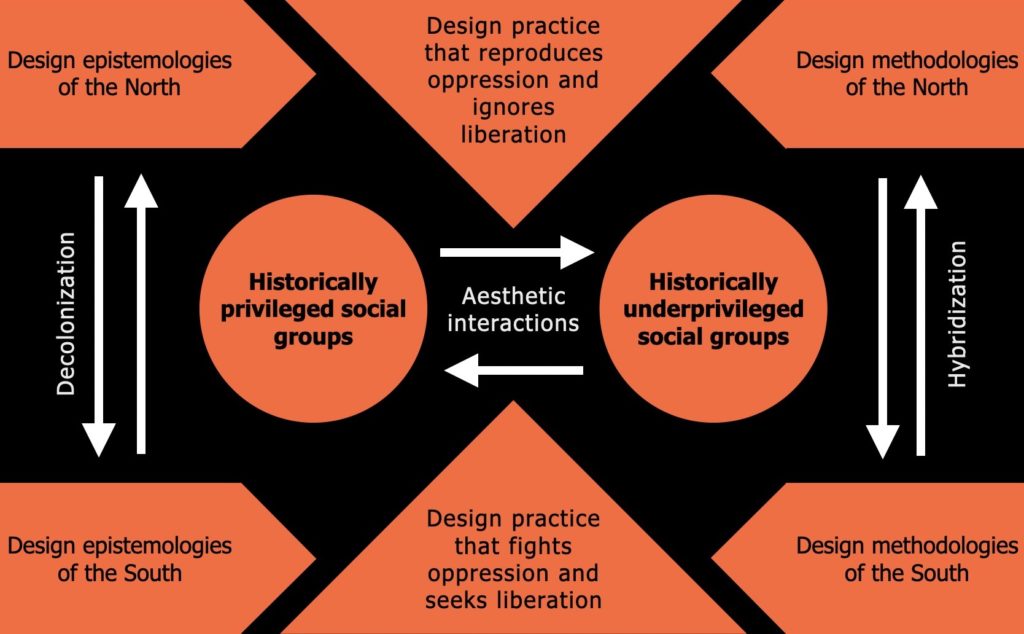

This realization has shaped our Designing for Liberation research program. At the top of our research framework, we have the historical legacy of design research—including epistemologies and methodologies of the Global North. At the bottom, we focus on design epistemologies of the Global South—which emerge from Indigenous, Black, and feminist traditions that have resisted dominant hegemonies.

These Southern epistemologies are diverse, but they share a common commitment to fighting oppression and seeking liberation. Our research places aesthetic interactions at the center of this struggle. We examine how historically privileged groups and historically oppressed groups interact through design. These interactions, in concrete practice, are where hegemony is either reinforced or disrupted.

At times, we turn to philosophical frameworks, such as Heidegger’s ontological design, to better understand how design shapes our ways of being. However, we also critically assess these frameworks, questioning whether they serve liberation or reinforce oppression. This often leads us to reject, adapt, or reconfigure Northern epistemologies in favor of methodologies that resonate with our own traditions. That’s it for now as a summary. I look forward to our discussion. Thank you for listening, and feel free to ask any questions.