Abstract: Twenty years of designing and researching across several disciplines led me to realize that transdisciplinarity is not the same as combining knowledge from different fields. Transdisciplinary design research means moving from one discipline to another to follow an expansive object. This is a reflection I presented as my first lecture in the MXD program at the University of Florida. Presented in the following linear format, this narrative does not account for all the moments of despair, frustration, sorrow, and feeling lost in my career. I underplay them here to paint a positive big picture in the spirit of US culture.

Video

Audio

Full transcript

This is going to be a very short summary of more than 20 years of doing design research. At the beginning, I didn’t know that I wanted to be in that field. And I don’t even think that I’m in that field most of the time. That’s why I say that I’m transdisciplinary researcher, which means that I’m in transition all the time—from one discipline to the other. I’m in always movement, from one to the other.

First, a disclaimer: Presented in this following linear format, this narrative does not account for all the moments of despair, frustration, sorrow, and feeling lost in my career. I underplay them here to paint a positive big picture in the spirit of being immersed in U.S. culture. This sarcasm is important, but it’s true. I want to have a short presentation, and I could for sure talk about frustration, sorrow, and feeling lost, but not on record. You can ask me later about this.

Let me start with my childhood. Of course, I knew right away that I wanted to be a design researcher like Gyro Gearloose, or Professor Pardal in Portuguese. In the U.S., he was not known as a professor, but in Brazil, he was. That’s funny, right? So, I already wanted to become a professor when I was a kid, and that’s a true story. I still keep asking why this Disney character became so important and inspiring for my childhood. I didn’t know much about it before building up this presentation. I figured out two things.

I grew up close to Rocinha, the biggest informal settlement in Latin America and one of the biggest in the world. I lived just near that big mountain on the right side. In the middle of the jungle, but still close to Rocinha. I was always passing by and being amazed by the cheerful vibrations that came from there. On the other hand, I also knew people, and I saw things that were very scary, like people holding big guns and actually hearing shootings, and the stories of people who had been killed by those shootings. Anyway, it was scary but also inspiring, especially because of the improvisation style that contrasted with the big modern development you see in the background.

Later on, I moved to Curitiba. I was still a kid. It’s a completely different city in southern Brazil. It is considered by some Curitibanos as the “Europe of Brazil.” They really feel superior in relation to the rest of the country—to the point that they started calling Curitiba the Republic of Curitiba. They have this famous, or now infamous, judge, Sergio Moro, who imprisoned the former president of Brazil, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (now the current president of Brazil). That was one of the major political upheavals and changes in recent years.

Lula was transformed into a corrupt politician by this city, but later on, he managed to underplay the role Curitiba played in major Brazilian politics. And then he became the savior of Brazil from Bolsonaro. Anyway, Curitiba has this ethos of being a modern, urban-planned city. I grew up in those two cities and went back and forth between them for a long time. I had to grow up between this postmodern and modern, or alter modern—if you want to call it that—which Rio de Janeiro is. That’s really an animating part of my story.

Experiencing the contrast between those two cities is probably one of the reasons I became interested in invention and design. However, I ended up not following an industrial design bachelor’s degree. I chose social communication because I thought everything I was reading and seeing from industrial design students wasn’t political enough. I really wanted to change the fundamental and unequal structures that I was seeing in those cities. Of course, in Rio, it’s more explicit, but in Curitiba, the same kind of unequal structure is present, just more hidden. I felt in love with writing and formatting that writing in an appealing way. So, I started to play around with newspapers.

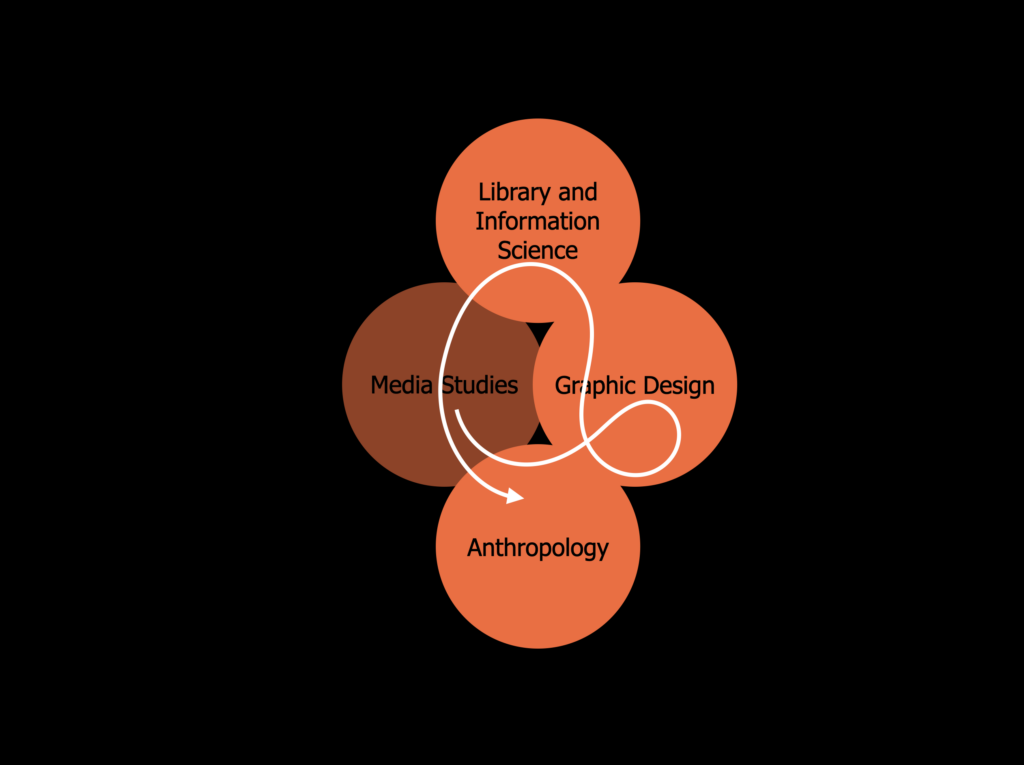

As a freshman, I published with my peers O Lenhador (The Lumberjack Man). We were denouncing all kinds of things we found weird or unethical at our university. We sold the newspaper to students so they could have arguments against faculty members during discussions. We were really trying to instill critical thinking in our university environment. While doing this, I somehow lost interest in journalism, which was my major. I started focusing on graphic design. I slowly moved from media studies—the equivalent of my studies in the U.S.—and combined those experiences while writing a web blog on web design.

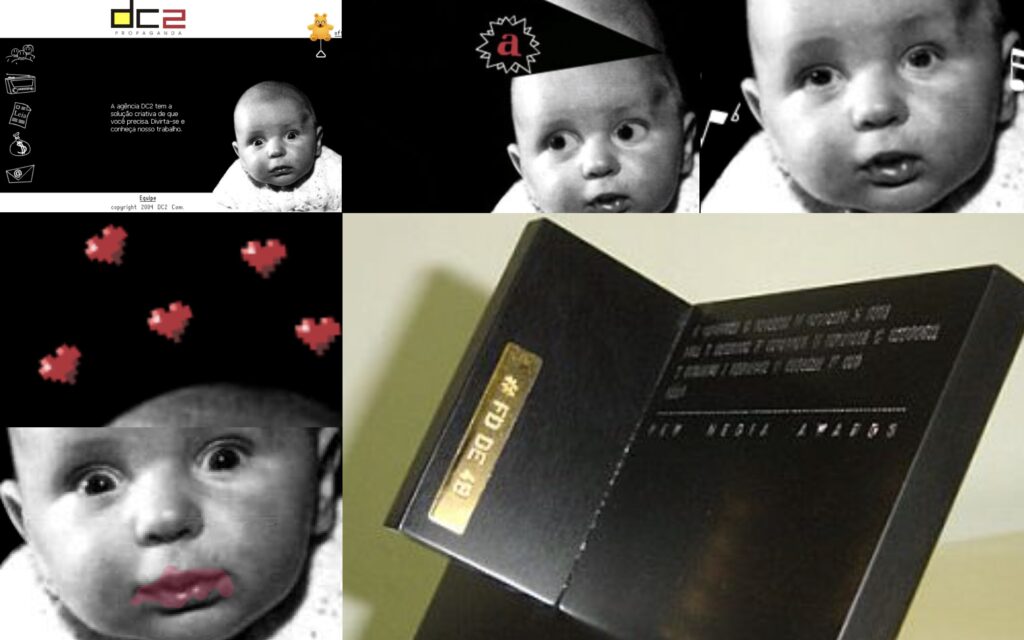

The blog is called Usabilidoido. I’ve been writing it for more than 20 years now, with over 1,000 posts. It’s all in Portuguese. I also have a website in English with much less content, but it’s based on that same experience. It’s less personal and more focused on my academic life. The Portuguese site has a lot of personal things. The website has changed a lot since I started, but I wanted to show you the very first layout. I was really young then. At that time, I was finishing my undergraduate studies and doing an internship at an advertising agency. I designed this website using Flash and later translated into HTML + CSS code. Flash was an interactive animation software that was really cool back then.

I ended up winning an award in an international competition for one of my Flash projects. It was weird—I didn’t have to pay the entrance fee because the conference Design Indaba was organized in the Global South. I later understood this; the conference was held in South Africa, and people from all around the world, especially those in need of recognition, could apply. They sent me a nice trophy, even though I couldn’t attend the ceremony.

I’ll quickly show you the website for fun because the context is important. I was becoming a dad at the age of 20. I was excited but also frightened. I had the opportunity to convince my boss that his advertising agency’s website should feature a baby. And so I did. Look at how it works! This is the menu for navigating the website—you drag and drop the options, something you’d never do now. There was even music! A website with music—wow. Those were good times.

Oh my gosh, this brings up a lot of nostalgic feelings. Every time you click one of these icons, you see the experience of the ad agency with that kind of media. So now we see DC2‘s experience with radio, where you could listen to their jingles. And for the logos they designed—of course, they offered graphic design services too. And it’s interactive—look, you can really explore the details of it.

For example, there is this little yellow bear at the corner of the screen. If you pull the string from it, you activate the background music. That’s Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5. My brother used to play that song all the time when I was a kid, and it annoyed me like hell. He had one of those toys with this music, and I destroyed the toy. But that music never left my head after that. That’s why I put it here.

After making websites like this, I felt in love with the medium. It became more interesting to me than newspapers. I started digging into web design. There were very few courses related to that at my university, but the library had a lot of books. I’ve mentioned this before—I read a lot of books there, and they were key to getting settled in that area for a while.

Here’s how my trajectory started to expand beyond my major. I began taking classes in information management and anthropology. Why anthropology? Because I realized that this medium was all about how people interact, understand things, and transform themselves. I had a hunch that it was all about becoming human. I couldn’t fully articulate that, but anthropology helped. Anthropology even introduced me to my first concept of interface. They used it to describe a space where the sacred meets the profane and anything can happen. Weird, right? But think about when a king addresses the people—that’s an interface where the powerful meets the powerless. Anything could happen, like people throwing tomatoes at the king, slightly diminishing his sacredness.

I soon became very concerned with technology and pursued a master’s degree in technology and society. That was the only program related to web design in my city. It was a very important moment in my life. We organized a lot of seminars—that’s where I learned how to do seminars. In this picture, we’re not doing a seminar; we’re organizing one. We were all grad students—crazy ones.

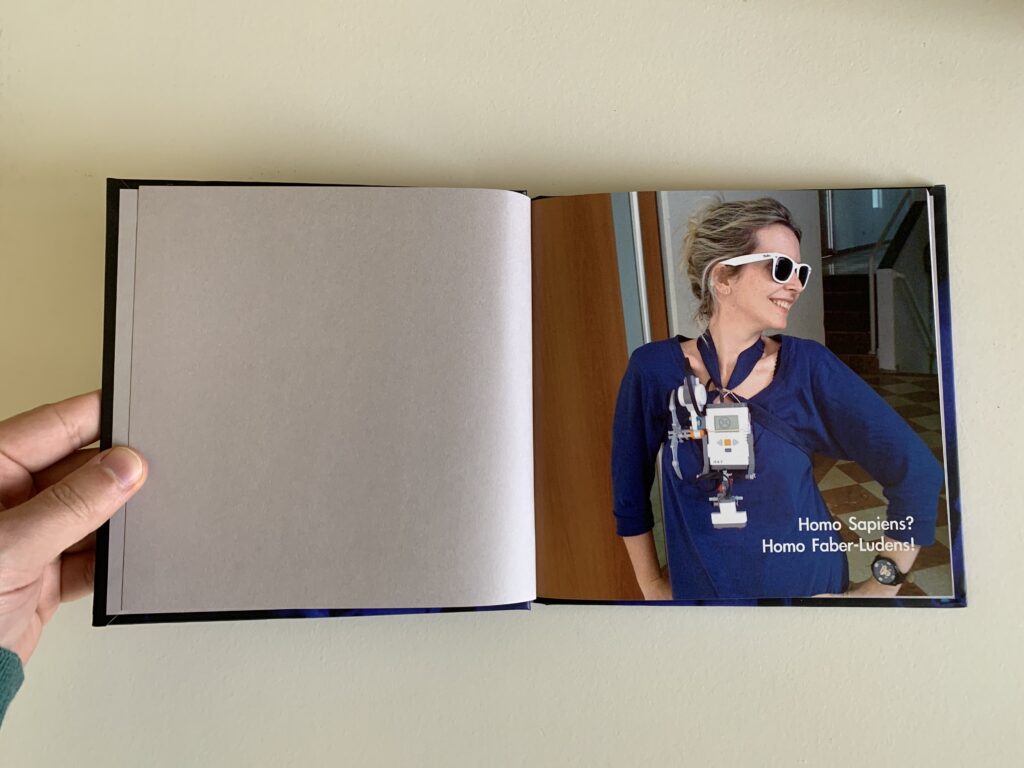

I read a lot during those two years—about 40 books a year. Everything I learned, I wanted to put into practice. Graduate studies focused on the humanities side, so I couldn’t build things, but I managed to create my own grad program with like-minded people. We called it Faber-Ludens Interaction Design Institute. It combined grad study, research facilities, and consultancy. We played around with digital technologies and developed a design approach. This was the beginning of a new field now called interaction design. It was loads of fun and really interesting.

The best part of that story was becoming fully conscious that design and education are about becoming human. That’s the background of the institute’s name. It was called Faber-Ludens because our vision of being human involves making your reality and playing with it. Faber means fabricating in Latin, and Ludens means playing. Our concept of being human isn’t about rational sapience; it’s about being a playful maker. We wanted to train people to become human in that way.

We realized that this was a privilege for those who could follow that course. So, we wanted to free design from designers. Not just for professional designers—people who don’t have access to training are also already designing. They’re becoming human by playing and making their own way. We wrote a book called Design Livre. It was also translated into Spanish as Diseño Libre. It’s a political pamphlet you can read in two hours or less. It’s about how design must be free from designers.

We built a digital platform to implement that vision. Corais Platform was a critical alternative to OpenIDEO‘s platform, which was big at the time. We were a Global South alternative, using non-English languages. Our platform offered digital tools that matched or even surpassed Google Drive’s capabilities back then. We competed with Google Drive—and in many features, we won. We were fast and cutting-edge. But this was more than 10 years ago. Our platform was basically an open-source software with lots of modules. Later, we compiled our learnings into a book called Coralizando. Like Design Livre, it was a collectively written book. We wrote it in a week using real-time text editing—not Google Docs, but our own platform called Etherpad. We still have this platform online, though it’s very outdated now.

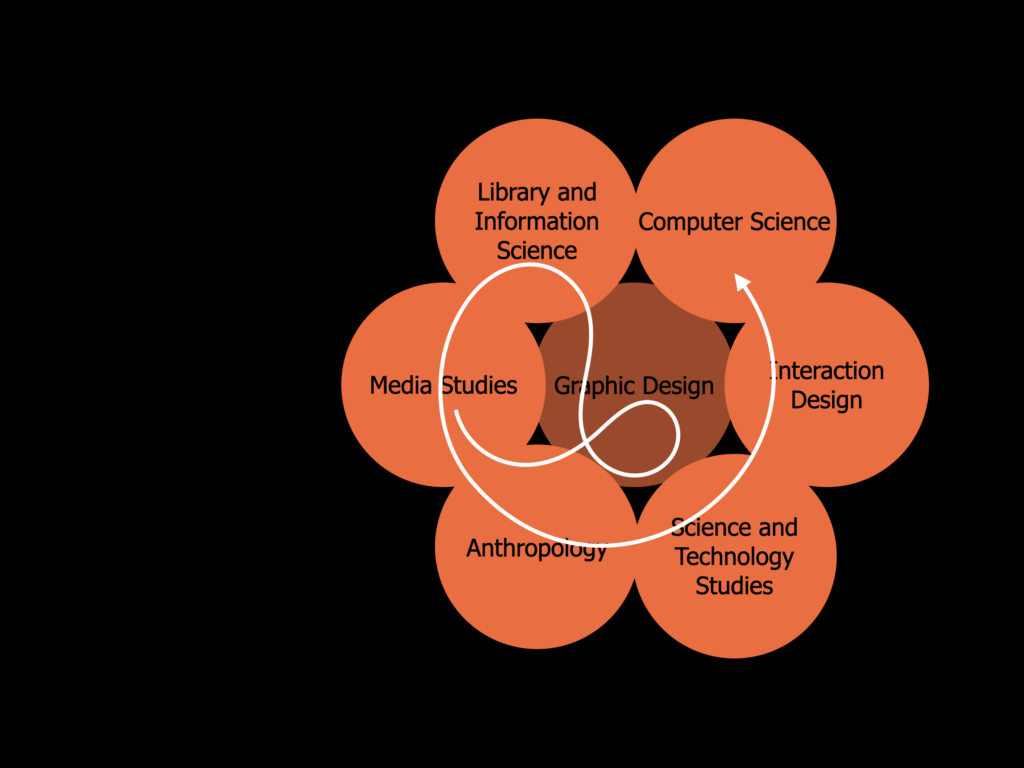

This experience expanded my trajectory. I moved away from graphic design. I became less interested in the graphic aspects and more interested in the structural side of design. Questions that concerned me were: how do you build a platform that can sustain itself for so many years? How can you build a platform that is still up after 13 years with no single source of funding? How can you do that? Only with open-source software and cooperative digital servers. I started learning all these things from other fields, like computer science. I also returned to information management.

I was focused on making a lot of stuff. However, once I started involving other people who found it hard to understand what was going on, I began writing. Writing was the best way to get everyone on the same page and have meaningful conversations or practical collaboration on these projects. I started to write, write, write, and publish my experiences. This also helped me access more funding.

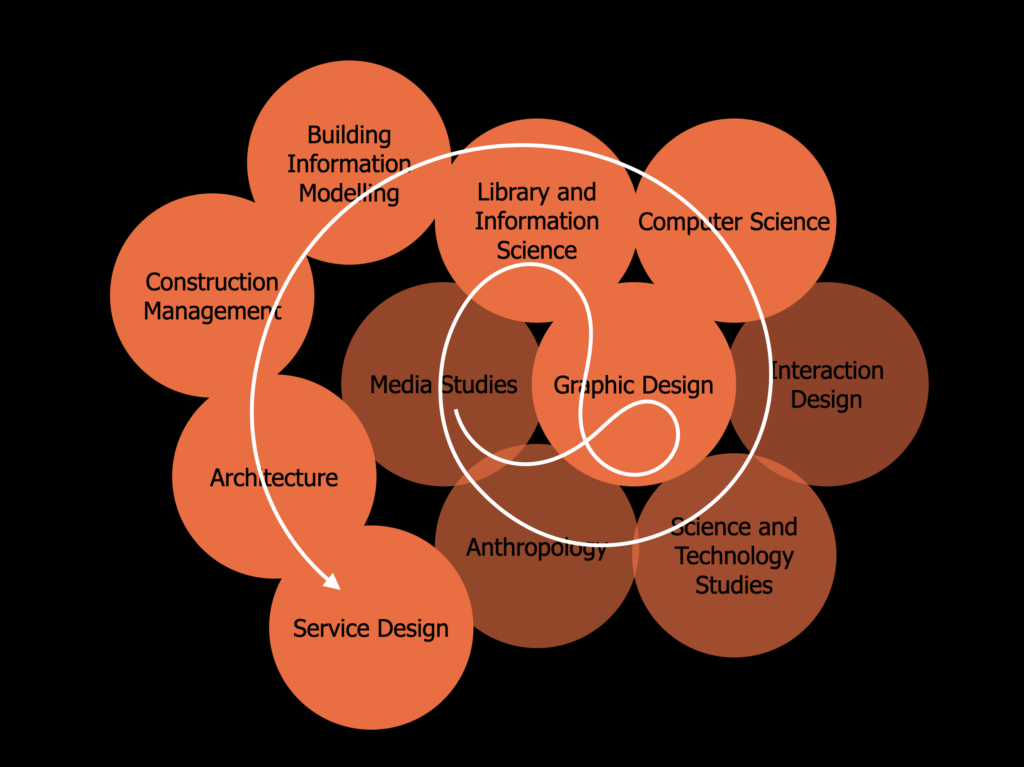

In my PhD at the University of Twente, I learned to conduct design research as a series of consecutive experiments. That meant professionalizing design research and doing it systematically. I returned to graphic design when I realized I needed to design games. I created a hospital design game where players took on roles like engineer, architect, facility manager, nurse, or even hospital director. Each role had a different political agenda. The goal was to collaborate for the common good while also ensuring you earned more money than the other players. That contradiction was the core of the game.

This contradiction also turned into a significant scientific discovery, which I made accessible to the public. I even played this game with Dutch kids. Even though I couldn’t say much in Dutch, they understood the real challenge of balancing personal and collective interests. In a capitalist economy, this conflict lies at the heart of many of our struggles.

In the Netherlands, one of the best things I learned was how to streamline design research as a productive process. I learned how to fund, execute, analyze, and publish research. In the picture, you see the first journal paper I published. It took me two years to get there, and it was really hard. But after that, many doors opened.

I won’t go into all those opportunities now, but publishing was a major breakthrough. Making my career milestones public allows others to build on them. For example, if you want to design a board game about hospital design, you can refer to everything I’ve done and improve upon it. Or, if you want to design a game in another field that explores conflicts between personal and collective interests, my work might still be useful.

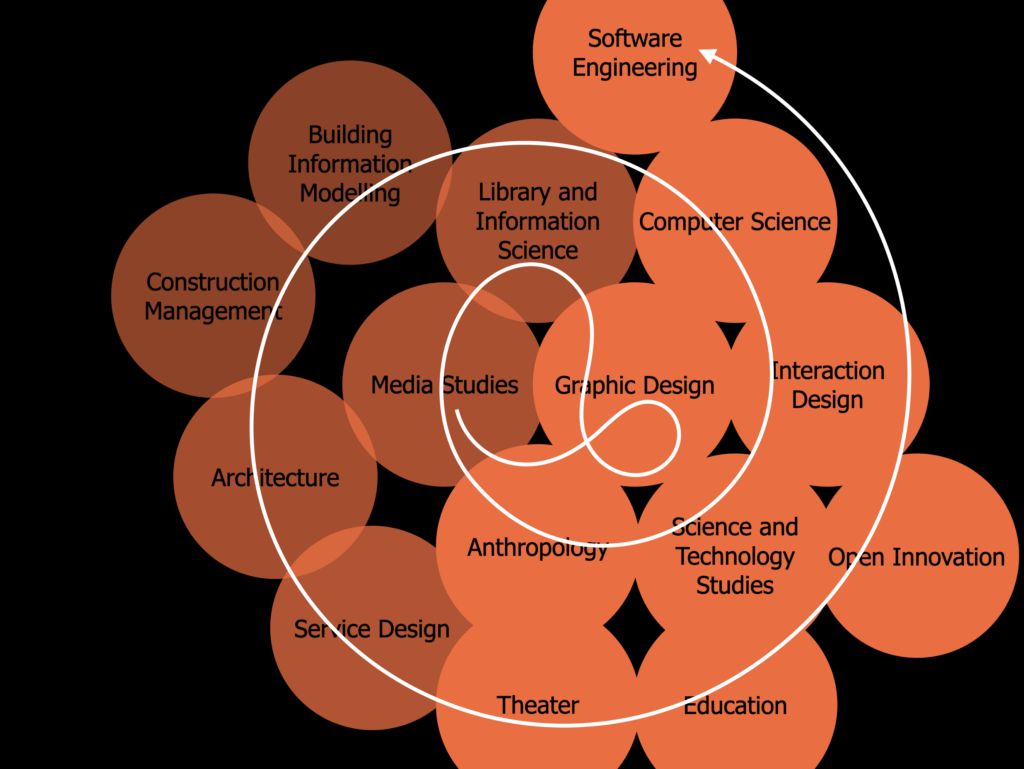

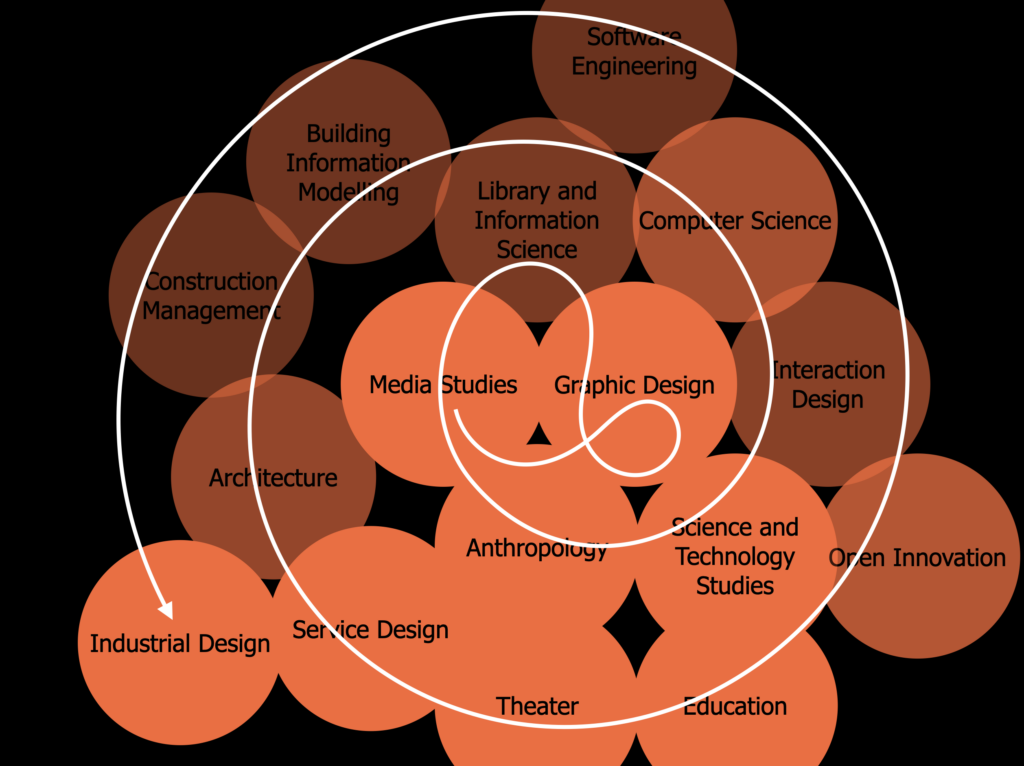

My PhD expanded my scope into areas like construction management and architecture. Eventually, I landed in service design, a design field that enables productive dialogues across disciplines. Currently, much of my work focuses on service design. However, I don’t consider myself just a service designer or say my research is limited to that field. I prefer to keep flowing through various fields. Those fields shown in subdued colors are ones I wasn’t active in during that period, but they might light up again later.

I conducted various experiments while teaching digital design at the Catholic University of Paraná (PUCPR). That was my first full-time academic position as an assistant professor, and they gave me a lot of freedom to experiment with teaching methods and students. During this time, I started applying Theater of the Oppressed to interaction design. In one of the pictures, you can see us using this method to understand and critique Instagram. The students were identifying the traps of Instagram at a time when public critical discourse on the platform wasn’t as widespread as it is now. In the picture, the students are wearing masks to explore the identities people create for others, which often conflict with their true selves.

Another important job I took on there was rebooting the University Innovation Agency, Hotmilk. We did a lot of work with startups and used co-design processes. This energized the community, and we developed many projects through the innovation agency. The best one was probably a digital platform for open innovation in the electricity sector, engaging startups in the production and distribution of energy in the state of Paraná.

There were some graphic design assignments as part of this project, such as organizing and producing animations to explain the challenges the legislation was facing. I think I spoke about this project in my previous guest lecture on expansive design. We played a lot of design games there. This research project had a budget of about $1 million, and I managed more than 10 people. I had to quit that job for reasons I won’t go into right now, but I can laugh about it later.

In parallel, I also worked for the Apple-funded developer training program. I managed to integrate design into the curriculum and created a transdisciplinary role called the devigner—a mix between a developer and a designer. A devigner can code as well as they can lay out elements for a graphic design project. This was a fascinating experiment. I miss being in that environment, especially because Apple already integrates a lot of critical pedagogy. They used a method called challenge-based learning, which is one of the most student-autonomy-enforcing pedagogies I’ve encountered.

It seems like things were getting confusing, right? That was me at the time. And honestly, I’m even more confused now! I was studying education, theater, software engineering, and open innovation—fields quite far from my initial trajectory. We published quite a few papers about this work. But the moment where I really found myself was probably in my last job, at the Federal University of Technology (UTFPR). The name is similar to UFPR, where I did my undergrad, but a different institution. Right when I started, Bolsonaro came to power and cut all budgets for research and teaching, nearly shutting down new public university development.

I had to discuss this situation with my students. Some supported Bolsonaro, and others opposed him. We wanted to have a conversation about it, so I designed the conversation. We created many things together, but one of the most striking projects was a wearable manifesto on politicizing design—from both right-wing and left-wing perspectives. For us, politicizing meant having a democratic discussion about what design is and could be.

Through that experiment, I realized I needed to acknowledge my own existential condition—as a privileged white, heterosexual, cisgender man (at least in Brazil). Acknowledging that privilege and deciding how to share it became a method for doing design research.

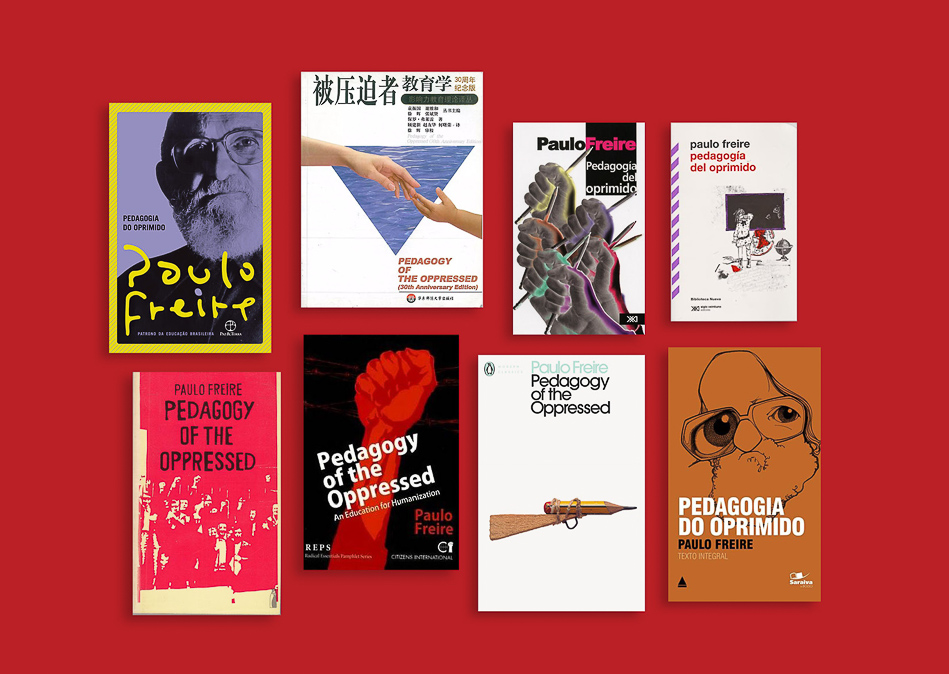

Around the same time, Bolsonaro supporters were publicly attacking Paulo Freire. You remember I mentioned him before? Paulo Freire was a Brazilian educator who developed a critical pedagogy approach that promotes student autonomy, critical thinking, and political awareness. His ideas bother those who want to maintain the status quo, typically Bolsonaro supporters.

Interestingly, these attacks sparked renewed interest in Freire’s work, both in Brazil and internationally. His works have been translated into many languages. He’s the most cited Brazilian scholar of all time, with over 400,000 citations on Google Scholar—that’s more than four times the citations of Albert Einstein. If you know about Einstein but not Freire, it’s because Freire comes from the Global South, and making his ideas widely known challenges those in power in the Global North.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Bolsonaro’s mismanagement led to devastating consequences. He downplayed the need for masks and lockdowns and promoted chloroquine as a cure, even though it wasn’t scientifically proven. As a result, 17,000 people died from using this medicine. In total, over 700,000 people died from COVID-19 in Brazil. Analysts estimate that at least 350,000 lives could have been saved if the pandemic had been managed better.

In this context, my colleague Marco Mazarotto proposed studying Paulo Freire’s work in relation to design. This idea laid the foundation for the Design and Oppression Network. Our online reading group grew into this network, with more than 600 people participating over two years. We conducted many design experiments, including remote Theater of the Oppressed sessions using 3D body models. These were exciting but also worrying times, given what was happening outside our homes.

We also founded the Laboratory of Design Against Oppression (LADO) as a local hub of the network at UTFPR. LADO became an official outreach project, connecting the university with the community and focusing on community benefit, not just student or university benefit. At LADO, we ran many experiments, particularly Theater of the Oppressed exercises to explore the embodied aspects of design. In one picture, you can see us understanding how design workers face pressure from their bosses and society, and exploring how to resist that oppression.

We also designed liberating projects, like a modular set of furniture that reused discarded materials, promoting sustainability and a dynamic lifestyle. The students even designed a CNC machine using modules they had created for that same furniture—a meta-design project and an example of open design.

One of our most significant discoveries was user oppression (or userism). This concept refers to reducing people and their full bodily experience to an abstract concept of a user. In today’s world, user oppression is so pervasive that users are often nothing more than AI agents generating random data to justify design decisions. If we continue designing products and services this way, we will all suffer.

Most recently, I’ve ventured into industrial design, learning alongside my students how to design physical objects—something I hadn’t formally studied before. This part of my journey is still growing, and I don’t know where it will lead. I gave you a glimpse of my current trajectory when I mentioned reading Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit. Perhaps I’ll move toward developing a concept of design consciousness to expand upon design thinking. This philosophical journey may take years to complete.

For now, I just want to say: this story is to be continued, and I hope you’ll be part of it. Please, join my trajectory!

References

GONZATTO, R. F.; AMSTEL, FMC Van; COSTA, R. C. T. Jogos e Humor nas Metodologias de Design. Proceedings do IX SBGames, p. 138-44, 2010.

AMSTEL, Frederick; VASSÃO, Caio A.; FERRAZ, Gonçalo B. Design Livre: cannibalistic interaction design. In: Innovation in design education: proceedings of the third international forum of design as a process. 2011. p. 3-5.

GONZATTO, Rodrigo Freese et al. The ideology of the future in design fictions. Digital creativity, v. 24, n. 1, p. 36-45, 2013.

SILVA, Claudia Bordin Rodrigues da et al. Consciência e ação em design de interação: recursos e práticas educacionais abertas para o esperançar. PPGTE (Tese de Doutorado). 2019.

GONZATTO, Rodrigo Fresse ; VAN AMSTEL, Frederick M.C. ; JATOBA, P. G. . Redesigning money as a tool for self-management in cultural production. In: PIVOT 2021, 2021, Toronto. Proceedings of PIVOT 2021: Dismantling/Reassembling Tools for Alternative Futures, 2021. p. 39-48.

de Siqueira, I. L. M., & van Amstel, F. M. (2023). Service design as a practice of freedom in collaborative cultural producers. In Proceedings of the Service Design and Innovation Conference (ServDes 2023), Rio de Janeiro. pp. 315-325. https://doi.org/10.3384/ecp203016

Van Amstel, F.M.C; Hartmann, T; Voort, M. van der and Dewulf, G.P.M.R. The social production of design space, Design Studies, 46, 2016, p. 199–225

VAN AMSTEL, Frederick MC et al. Expensive or expansive? Learning the value of boundary crossing in design projects. Engineering project organization journal, v. 6, n. 1, p. 15-29, 2016.

VAN AMSTEL, Frederick MC; GONZATTO, Rodrigo Freese. Design Livre: designing locally, cannibalizing globally. XRDS: Crossroads, The ACM Magazine for Students, v. 22, n. 4, p. 46-50, 2016.

VAN AMSTEL, Frederick MC; GONZATTO, Rodrigo Freese. The anthropophagic studio: towards a critical pedagogy for interaction design. Digital Creativity, v. 31, n. 4, p. 259-283, 2020.

VAN AMSTEL, Frederick MC; GONZATTO, Rodrigo Freese. Existential time and historicity in interaction design. Human–Computer Interaction, v. 37, n. 1, p. 29-68, 2022.

DORS, TANIA MARA ; VAN AMSTEL, FREDERICK M. C. ; BINDER, FABIO ; REINEHR, SHEILA ; MALUCELLI, ANDREIA . Reflective Practice in Software Development Studios: Findings from an Ethnographic Study. In: 2020 IEEE 32nd Conference on Software Engineering Education and Training (CSEE&T), 2020, Virtual Conference. 2020 IEEE 32nd Conference on Software Engineering Education and Training (CSEE&T), 2020. p. 1.

GONZATTO, R. F.; AMSTEL, FMC Van; COSTA, R. C. T. Jogos e Humor nas Metodologias de Design. Proceedings do IX SBGames, p. 138-44, 2010.

AMSTEL, Frederick; VASSÃO, Caio A.; FERRAZ, Gonçalo B. Design Livre: cannibalistic interaction design. In: Innovation in design education: proceedings of the third international forum of design as a process. 2011. p. 3-5.

GONZATTO, Rodrigo Freese et al. The ideology of the future in design fictions. Digital creativity, v. 24, n. 1, p. 36-45, 2013.

SILVA, Claudia Bordin Rodrigues da et al. Consciência e ação em design de interação: recursos e práticas educacionais abertas para o esperançar. PPGTE (Tese de Doutorado). 2019.

GONZATTO, Rodrigo Fresse ; VAN AMSTEL, Frederick M.C. ; JATOBA, P. G. . Redesigning money as a tool for self-management in cultural production. In: PIVOT 2021, 2021, Toronto. Proceedings of PIVOT 2021: Dismantling/Reassembling Tools for Alternative Futures, 2021. p. 39-48.

de Siqueira, I. L. M., & van Amstel, F. M. (2023). Service design as a practice of freedom in collaborative cultural producers. In Proceedings of the Service Design and Innovation Conference (ServDes 2023), Rio de Janeiro. pp. 315-325. https://doi.org/10.3384/ecp203016