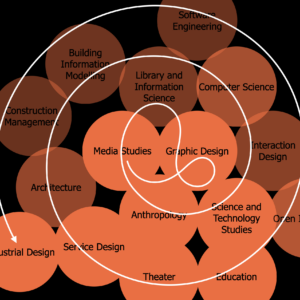

Throughout the 20th century, there were many attempts to make design into a single and unified discipline, similar to (or even engulfing) architecture. These efforts failed as new design disciplines kept popping up and creating distinctive professions. The possibility of disciplinary unification under elusive labels like design studies became less and less realistic as designers embraced collaborative, participatory, and open approaches.

Designers wanted to be recognized as a discipline in multidisciplinary teams. Instead, they were called in by society to facilitate, complicate, or integrate knowledge from multiple disciplines. Design, as a mode of disembodied thinking, was then reconceptualized as an interdisciplinary activity, “the glue between all disciplines”, as Arne van Oosterom (and many other consultants) proclaimed, probably inspired by the 2005 interview of David Kelley by GK VanPatter.

This did not last either. Stark conflicts arise when mending the work of different disciplines. Disciplinary boundaries are typically laid out by their pioneers with no appreciation, recognition, or respect for those who have thought or made something in that same knowledge space before them. Most disciplines rise from visionaries who once looked above everyone else. Knowingly or not, they colonized people’s mental space pretty much like the metropolises colonized Indigenous territories as “unused lands”.

Disciplines rarely openly negotiate their boundaries and designers are in no position to act as interdisciplinary referees. After all, designers have no discipline of their own—at least not one recognized by other disciplines as a discipline (most see it as undisciplined art). Then, the most resourceful discipline prevails over the others, even if claiming interdisciplinarity.

To avoid the contradiction of intra-inter-disciplinarity, designers are recently experimenting with transdisciplinarity. Working across (or despite) disciplines seems more peaceful but it is not. What differentiates transdisciplinarity from interdisciplinarity (which also unfolds across disciplines) is the transcendence of discipline itself!

Who in the hell would think that disciplinary people would happily join a space where they would lose their disciplinary power? Even the best motivation for the greater good of (Noratlantic) humanity cannot persuade codesigners to collaborate despite disciplines. Disciplines always strike back.

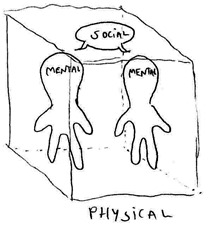

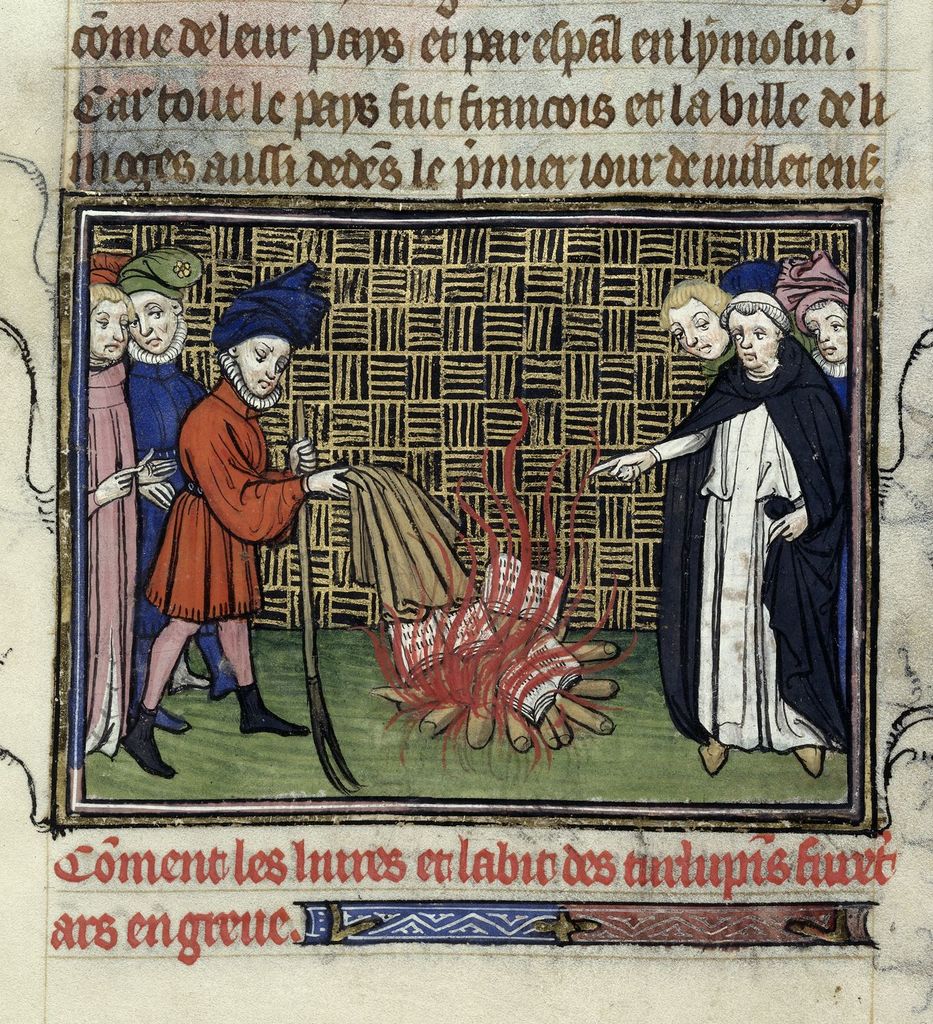

The only way to keep a balance of forces is to have codesigners who embody non-disciplinary or non-academic knowledge present, like Indigenous people and other people kept apart from academia. Academics like to think of themselves as being caretakers of the entire knowledge of the history of (Noratlantic) humanity, yet they can only sit on top of a small fraction of it. Most of it has been ignored, erased, neglected, forgotten, or burnt down.

First of all, there are other humanities, or in other words, other ways of being human that aren’t covered by the Western notion of “humanity”—hence why designing for humanity is not transdisciplinary at all. Second of all, there are other (non-designerly!) ways of knowing that never end up written in a paper or manufactured into an industrial product.

Whenever disciplinary boundaries curtail the necessary knowledge to overcome a pressing contradiction in society, these need to be temporarily lifted or destroyed. For instance. Eugenics used to be a scientific discipline of human improvement that prevented society from overcoming the contradiction of racism. Even if disciplinary people still try to revamp it to design babies and surveillance systems, this is still considered to be a harmful pseudoscience.

What can designers do in such cases, if they are commonly associated with construction instead of destruction? Can designers, let’s say, destroy racism or systemic oppression in general? Can designers design against something instead of for something? As you can see in the previous links, I’ve been thinking (and doing something about) deeply about this.

Yes, I believe designers can do a lot, but they first need to overcome their inherited prejudice over transgression, an attitude consolidated and embodied by social movements. Once overcome, designers can then see that transdisciplinarity is transgression, a praxis that fundamentally challenges the existence of fixed disciplinary boundaries.

Make no mistake. Every academic discipline exists to control knowledge, which is not per se a bad thing. If disciplines could not overrule another, we would still have Eugenics (and we may have it back if current established disciplines do not stand against its new incarnations and traces left in other disciplines). Still, boundaries can, by themselves, be very oppressive.

In my transdisciplinary adventures, whenever I felt excluded and oppressed by a discipline, I’d jump to another and see if I could continue my work there. Sometimes, I’d return to the oppressive boundary, leave marks on its cracks, and indicate to other people how they can cross or break them. The freedom I seek cannot be contained by one single discipline, therefore, my adventure never ends.

Here is a recent story from my adventures. Earlier this year, I was invited by Cristina Zaga, Julieta Matos-Castaño, and Mascha van der Voort (former PhD supervisor) to join their DRS 2024 conversation. The title was Transdisciplinarity: Taking stock beyond buzzwords and outlining an agenda for design research. You can read the conversation report by following the link above.

In it, I spoke a few minutes about my vision of transdisciplinarity, summarized by them as such:

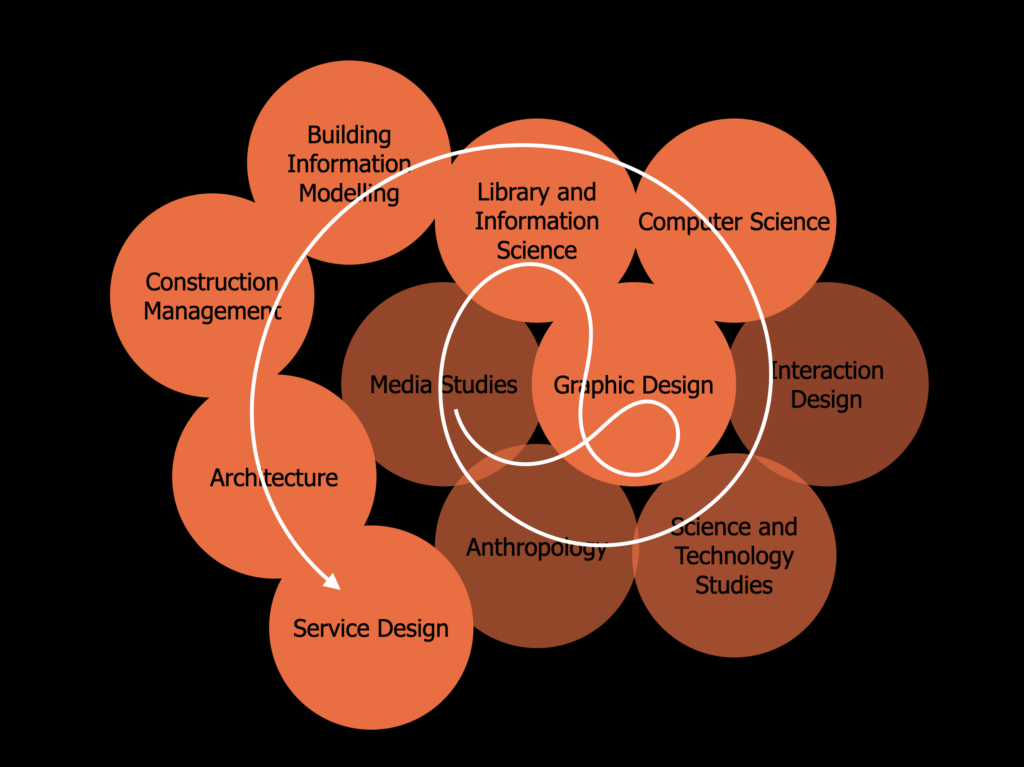

Dr. Frederick van Amstel (University of Florida) represented a perspective from pluriversal design, decolonial design and the politics of design related to matters of oppression. He introduced a figure sharing his “transdisciplinary adventures, moving from one discipline to another, eventually going through uncharted knowledge spaces, in a never-ending expansive spiral. Transdisciplinarity for me

is transgressing the disciplinary inward-facing linear movement of knowledge production” (Zaga et al., 2024).

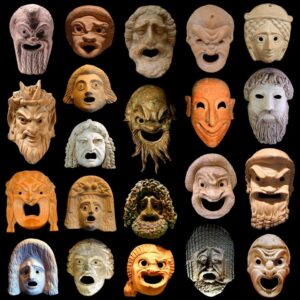

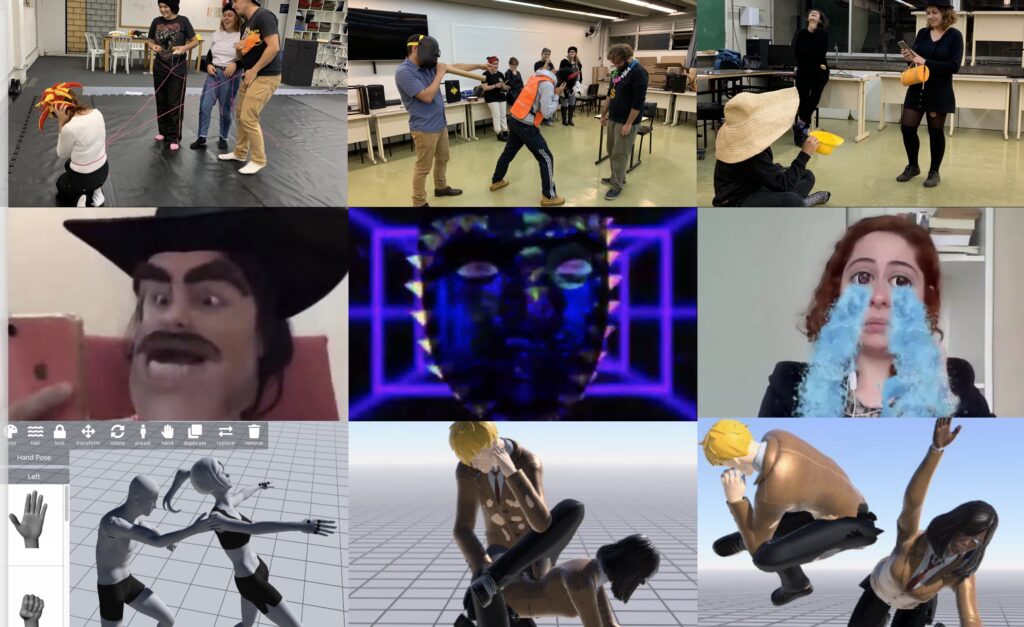

After that, the attendants were divided into groups. The ones who flocked around my vision of transdisciplinarity as transgression had a surprising moment. Instead of the traditional speech-based conversation model, I invited them to experience transdisciplinarity with their full bodies. I told them that I had a Theater of the Techno-Oppressed workshop proposal rejected by the DRS 2024 committee. The proponents were me, Bibiana Serpa, and Fernando Secomandi, from the Design & Oppression Network. This is what we proposed:

The workshop is a full-day, in-person, full-body experience. The first part of the workshop is dedicated to demechanizing the participant’s bodies, thus avoiding automated behavior such as academic conference interactions and White supremacist design discourse.

This is how it was received by one reviewer:

At a first glance, the proposal looks promising in questioning current models and mindsets in design, however the focus is more on the role of technology in mediating oppression relations and explicit connections with design and design research are announced but not fully elaborated.

Clearly, disciplinary boundaries were evoked to protect the design research field from our anti-racist creative criticism. Looking at technology as mediation is already a well-established design research approach, particularly in the interaction design discipline. My Master’s thesis already made that claim in 2008. Why would we need to fully elaborate on that in a 750-word workshop proposal? Citing our paper on user oppression seemed to be enough to us but unfortunately, it wasn’t enough for the reviewer.

We could have complained about the poor reviews we got but we preferred to accept it as part of the rigged game we accepted to play. I say rigged because we from the Global South lose or are excluded from the game most of the time, be that through language (English is not our mother tongue), money (our Brazilian institutions are not plenty), epistemological differences (what is knowledge to us is not knowledge to others), and unequal citation patterns (we receive fewer citations than other authors).

As authors coming from the Global South and some of us (me and Fernando) now positioned in Global North institutions, we are still a historically oppressed social group in academia (because our bodies accumulate a history of denied access), we wanted to share embodied knowledge traditionally neglected in design research, and we were dismissed by those who are privileged enough to ignore this history and get away with that… as usual. This is surely not the first time this has happened and it won’t be the last. That is why we need to keep pushing those oppressive boundaries away.

As I saw it, the conversation on transdisciplinarity was the opportunity I had to reclaim what was taken from us—and from the Noratlantic design research community who never joined a Theater of the Oppressed workshop. It is worth mentioning that reading descriptions about such workshops, attending paper presentations, or watching tutorial videos is far from the actual lived experience of actually joining a workshop. When the oppressed lose, the oppressor also lose the opportunity to humanize, as Freire has remarked.

Only someone who never has gone through a similar embodied experience, i.e. who never experienced developing critical body consciousness, can deny that. For those people, several exercises are necessary to warm up the body and raise critical consciousness. That is why we proposed a full-day workshop in the first place. Unfortunately, this aspect of the proposal was the main argument used by another reviewer, who just wrote the following:

An interesting concept but think the ambitions and the scope (in particular, a full-day session) are beyond our constraints for this conference. I also have concerns that the activities mentioned here don’t seem well-delineated or detailed enough to suffice a full day.

If no full-day workshops were accepted, we would be ok with this comment. But that wasn’t the case; another full-day workshop moved forward. Again, I am not sharing these reviews to complain about such poor reviews. I am just making the design research disciplinary boundaries explicit in a field that proudly (or naively) claims to be interdisciplinary and sometimes transdisciplinary, a contradiction I cannot remain silent about.

Authentic transdisciplinarity means transgressing disciplinary boundaries. I prefer to call it transgression instead of transcendence to emphasize the objective nature of such action. Zaga, Castaño, and van der Voort know that very well, hence, they did not block my attempt to hijack their conversation. Here is what I proposed to my group (the smallest in the in-person space I must say):

Let’s have a full-body conversation. Let’s talk through our body postures, silent gestures, and enacted rituals. Let’s avoid talking through speech, which is by the way, how anglophane people take privilege in international conferences.

We played several dramatic games, including one of my favorites: Toré Yanomami, which I learned from Bárbara Santos, an artist-researcher who is at the forefront in that praxis, and the CTO Jokers. The purpose of this game is to dance what brings us together through the vowels of our names. It is a form of Indigenous embodied knowledge translated by Theater of the Oppressed practitioners to emphasize unity in diversity. Full disclosure: I have Indigenous ancestors from the Apurinã people, but I know as little of their culture (due to the systematic erasure of that ancestor’s contribution to our family) as I know of the Yanomami culture.

I just wanted to make the point that Indigenous knowledge has been historically excluded from academic disciplinary knowledge and that embodied knowledge was precious and very much needed in times of extreme social fragmentation. We also played further dramatic games originating from other social movements. By the way, social movements often promote such embodied interactions to produce mutual awareness (or as I prefer to call critical body consciousness) of their collective bodies.

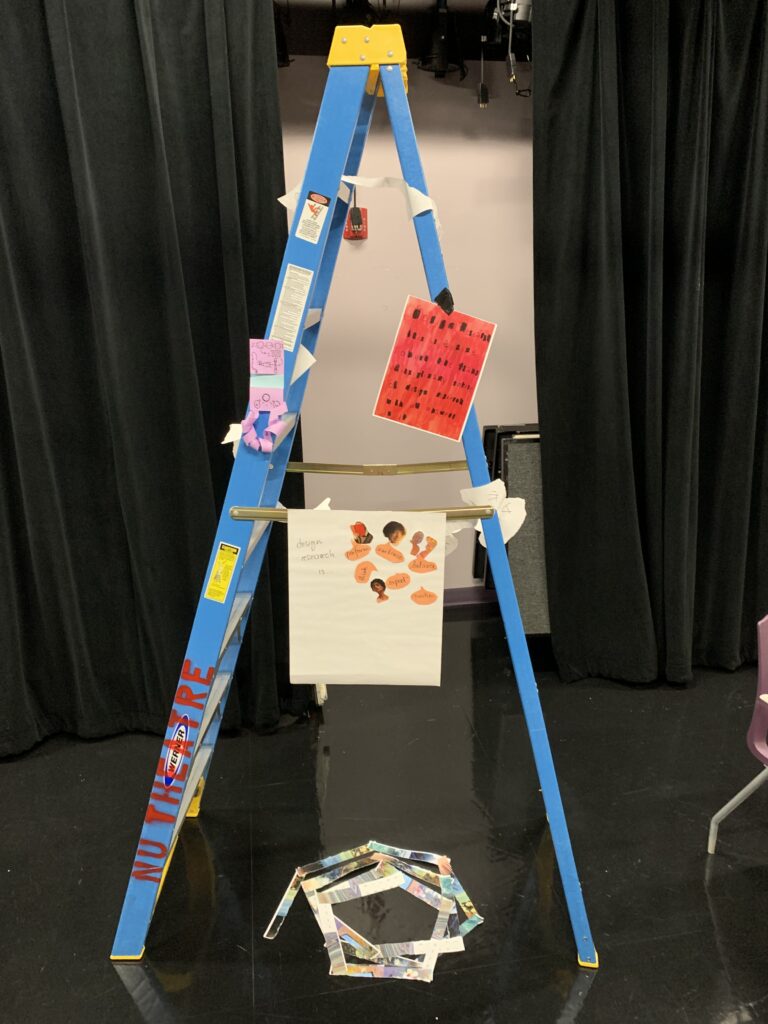

After the speechless conversation, we resumed talking and included permanent materials to express how we felt about the topics we discussed. Each one of us made something different with our hands. To integrate them, I fetched a staircase hanging at the corner of Northeastern’s University acting studio—a fortunate location for the conversation. What came out of that ressembles what typically comes out of an Aesthetics of the Oppressed workshop, an expansion of Theater of the Oppressed left by Boal in his final years and picked up by Bárbara Santos. We did all of this in less than 40 minutes with no rush, which is an amazing achievement of that open-minded and body-positive group.

Having the following recognition by Zaga, Castaño, and van der Voort in their report is priceless as it stands as an example of how people from the Global North can acknowledge and learn from people from the Global South:

Frederick van Amstel invited to reflect participants about crossing boundaries intertwining transcultural relations, de/colonization and disciplinary practices. Transdisciplinary exchanges involve multiple worlds and contradictions that tend to remain hidden and tacit. To foster transdisciplinary practices, it is therefore important to make them visible. Transdisciplinary calls for ‘hijacking’ the system, challenging the status quo and predetermined scripts on how disciplines and activities have traditionally operated. By not accepting traditional ways of thinking and doing, transdisciplinarity encourages the exploration of alternative methodologies, and questioning the underlying assumptions that govern disciplines and societal structures. While this might disturb usual practices causing confusion and discomfort, it ultimately provides alternative and insights through disruption and subversion (Zaga et al., 2024).

Of course, I would have preferred to have hosted our Theater of the Techno-Oppressed workshop (as we did in ServDes in Rio de Janeiro). Yet, I took the opportunity to hijack a piece of that workshop as part of an accepted conversation to make a valid point (at least from the point of view of its hosts) on transdisciplinarity as transgression. Not many people joined us and not many people understood why I did that. For those puzzled or suspicious, I hope this blog post helps.

In sum, transdisciplinarity is not yet another way of making (Noratlantic) design richer, more diverse, and more effective. Instead, it is better understood as an opportunity to transgress boundaries, welcome historically excluded non-disciplinary knowledge, and lay the path toward decolonizing design research. Transdisciplinarity that does not welcome transgression is just interdisciplinarity, multidisciplinarity, or plain disciplinarity, blatantly disguised as transdisciplinarity.

References

Zaga, C., Matos-Castaño, J., and van der Voort, M. (2024) Transdisciplinarity: Taking stock beyond buzzwords and outlining an agenda for design research, in Gray, C., Hekkert, P., Forlano, L., Ciuccarelli, P. (eds.), DRS2024: Boston, 23–28 June, Boston, USA.https://doi.org/10.21606/drs.2024.1566