Abstract: What is design research? How does it differ from design activity? Consider this distinction regarding the activity’s object. Design activity may be an object of design research in research about design. Yet, in research through design, the research object is shared with another activity, for example, another science. Drawing from personal experiences in hospital and service design, the lecture details how objects move through stages of motivation, confrontation, transformation, and reflection. It highlights the collaborative power of design games in bridging practitioner and researcher activities, revealing underlying contradictions. Influenced by Álvaro Vieira Pinto and Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, the lecture posits that design research objects define researchers as they engage in continuous transformation with the world around them.

This lecture was recorded in the Fall 2024 Research and Practice MXD MFA course at the University of Florida.

Video

Audio

Full transcript

The purpose of this lecture is to give you an overview of the kind of research that I like doing the most and that I’m most interested in. I’m going to revisit my historical design research trajectory and how I encountered my research objects and how it changed over time. That’s important for you as you are becoming a design researcher and finding objects to deal with. You may ask right away why I’m talking about objects instead of subjects, topics, or themes. You will see throughout my presentation that I have a theoretical background that emphasizes objectivity as much as subjectivity, and the interaction between them is precisely where my kind of design research is situated.

To begin with, I prefer to start with objectivity rather than subjectivity. I’m going to encourage you to find objective grounds for your research, so you start from something that is already there in the world instead of relying on an idea in your head and waiting for that moment of inspiration to come to you. I don’t believe that’s the best way to start design research, but of course, I respect and admire people who wait for those insightful things to come up in their minds. Some people are getting results with that subjective approach, but that’s not my cup of tea.

Here’s my PhD thesis, which I completed before my defense in 2015. I identified, among many things, a contradiction in expanding design objects. I already discussed this contradiction in the Spring 2024 Graduate Seminar. Second-year students know about designing emergent performances and these contradictions of moving from information and complex entities to emergent performances, meaning interactions, information, and experiences, which are currently designable objects.

Here, you can see what happened in terms of disciplines in one slide. There was a multiplication of new design disciplines. What was once graphic design and product design has now expanded into UX design, interaction, service design, product design, sustainable design, information design, you name it. Why is that happening? Because we are trying to grasp a new object that is less physically and conceptually bound to one thing. Even graphic design has products as an outcome, whereas these new fields don’t have a particular product. They may even claim there’s no product; we want to deliver processes, especially in service design.

However, the contradiction is that at the same time this transformation is happening, representation instruments or tools—e.g., design tools and design software—are becoming less and less expansive or, to put it another way, more reductive. So, if in the past, designers would do a lot of sketches, visual thinking, drawings, mock-ups, bubble diagrams, and ways of grasping this object in a much more manual, sensible, and emotional way, nowadays it’s getting more rationalized, instrumentalized, data-based, and overly structured, like computer-aided design or CAD for short, building information modeling or BIM for short, and machine learning models similar to the ones used by ChatGPT and its image generation system called DALL-E.

I’m talking about a contemporary contradiction that is getting worse as these technical tools become available and threaten to replace human activity, becoming an automated design process. It’s the opposite of what the disciplines are trying to do with expanding design objects, right? And that’s what a contradiction is: two forces going in opposite directions that cannot be eliminated because they interpenetrate each other, and you cannot get rid of either. You have to handle a contradiction.

I first identified this contradiction in the realm of architectural design. I focused on this transition over the last 400 years when the construction site was the design object, and there were no drawings or visualizations before builders started to build cathedrals. Then, when their professional trade became compartmentalized with the definition of the architect’s role as a leader or thoughtful intellectual behind the design, the paper sketch and, later on, the drawings became available. Recently, with an increased division of labor, architects are no longer the managers and leaders of construction projects. Now, engineers are taking over, even managers with no technical skills in construction whatsoever; they lead. Then, computer-aided drawings and even building information modeling are becoming more commonplace.

As I mentioned before, this is reducing the humanistic potential of architecture. It’s been a common topic of complaint in literature and at practice conferences, but they don’t know what to do about this, and in design research, we have some ideas. I started to approach this contradiction in my research through many different ways because, in the end, this resulted in failing to account for people’s needs, especially people who didn’t have a say in their projects, like those who were not considered stakeholders, they were non-holders, users, or even non-users or unwelcome people.

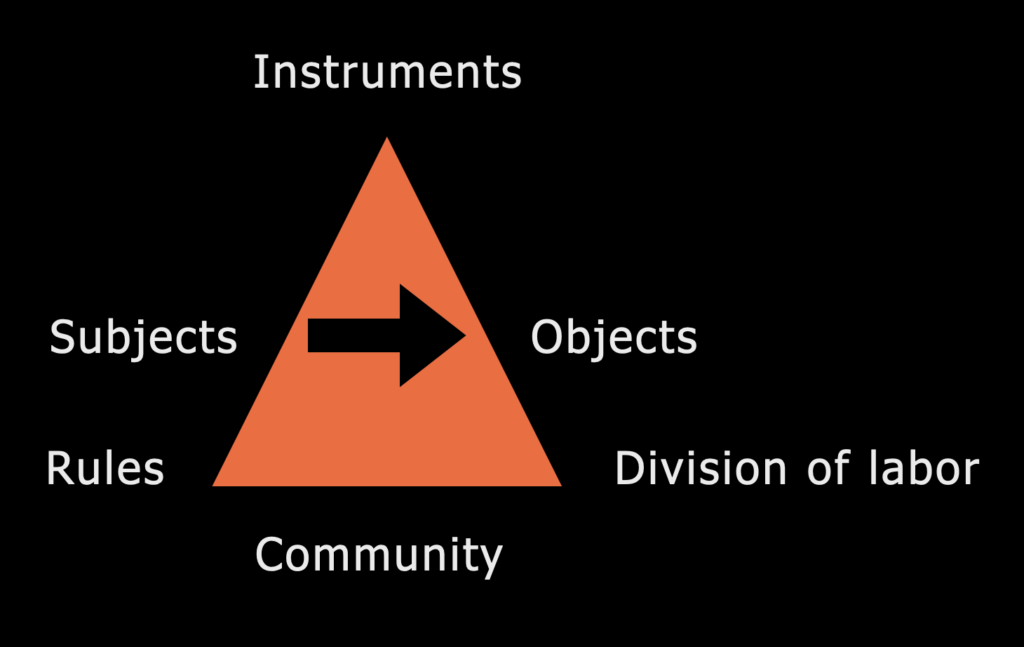

I came to this insight after applying a specific social science theory called activity theory and rigorously studying, as well as doing qualitative data analysis on design activity, a particular kind of design activity I’ll explain to you later. Before I characterize the concrete setting of my research, I want to give you an overview of this theory because I will use it to present my data, so you need to understand the model behind it. I cannot go too much in-depth into that; unfortunately, we don’t have time for that in this initial research and practice course. Maybe we may go deeper into activity theory in the second research and practice course this year.

It’s essential that you give me feedback if you find this necessary, interesting, or relevant to you, as it can be used for organizing qualitative data analysis and prioritizing your design activity. The model says the following: every activity has some basic elements that interact amongst themselves, and they eventually get into contradiction. Sometimes a subject trying to transform an object, which is the basic unit of an activity, cannot find a proper instrument, or the instrument does not fulfill that goal of transforming the object in a proper way. Then, you have a contradiction between subjects, instruments, and objects. You often find multiple contradictions—not just between those elements but also subjects against the rules, subjects against the visual labor, objects against the rules, and objects against the community.

By having all these major six elements laid out in this model, Yrjö Engeström, a Finnish scholar, devised a way of doing qualitative data analysis or, let’s put it another way, of doing engaged, interventionist research in organizations in a pretty straightforward way. A lot of people have followed this model in many other fields. I’m one of the first to pick up this model in the design research field, to delve deeper into applying the entire framework, to question the framework critically, and to complement it with our tradition of designerly ways of knowing. I cannot go into the details of this theory too much, but the most important thing is that an activity is constantly changing, and the instruments will be different in the future, as much as the objects, the division of labor, community, rules, subjects, and so on.

These contradictions will push the activity to change and become another one, and that’s why you can talk about a life cycle for an activity as the gist of this model. The model does not try to understand an activity at a particular time, although you can do that. The best usage is to survey the activity many times and then show the difference across history. So, you show that an activity was performed in one way 10 years ago and is now performed differently, or you can use even a smaller time scale, like how the activity changed over months.

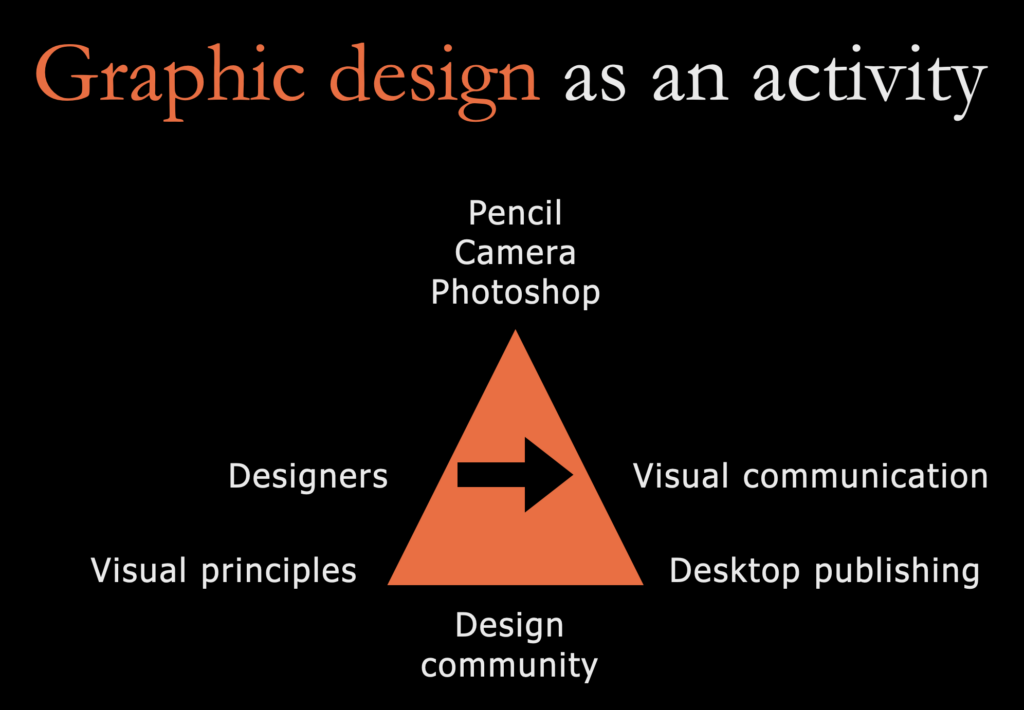

I mentioned to you I’m going to go back again to this disciplinary expansion of design, and I’m going to focus on two examples where I’m going to apply the activity system model: how graphic design expanded and became part of service design. I don’t mean that graphic design no longer exists; I’m just saying that service design draws on many graphic design elements, but it also draws on management and many other disciplines that have nothing to do with design.

Here’s the activity system model for graphic design, and that’s, again, an oversimplified view of a universal activity that can happen anywhere in a modern capitalist society nowadays. It used to be the case that graphic design was done with pencil and paper, but cameras, digital cameras, Photoshop, and even artificial intelligence are increasingly becoming instruments of graphic design. Starting with instruments is easy to understand because it’s very objective, but you have to define who’s doing that. Then, the second element of looking at an activity is who’s using those instruments, and then you see designers using those instruments to do what? What are they transforming, producing, and offering to society? That’s the right side of the triangle and where the arrow is pointing.

The arrow means this is the desired outcome, but it’s also objective. So, an activity is oriented towards an object, and that object is visual communication. Graphic design is trying to transform visual communication, and that’s one of the reasons why the program we are in is called Design and Visual Communication. In the past, it was called graphic design, so now we are trying to figure out the object. So, what is the most essential thing about graphic design? It is the object.

Beyond that, what is the context in which graphic design activity happens? Well, it’s a context forged by the design community that has desktop publishing as the primary division of labor, where one designer creates something, prepares a file, closes the file, and sends it to a printer, publisher, or manufacturing workshop that will execute that design. There is very little direct communication or dialogue between designers and producers.

But on the other side of it, you also have to acknowledge visual principles like the Gestalt perception rules identified by German psychologists, widely followed by modern graphic designers, color theory, and many other principles used for creating what is recognizable as professional graphic design. This is in contrast to indigenous, popular, naive, or amateurish design that you can find on social media or the streets, which is considered non-design. But that’s how graphic design justified itself as a professional activity.

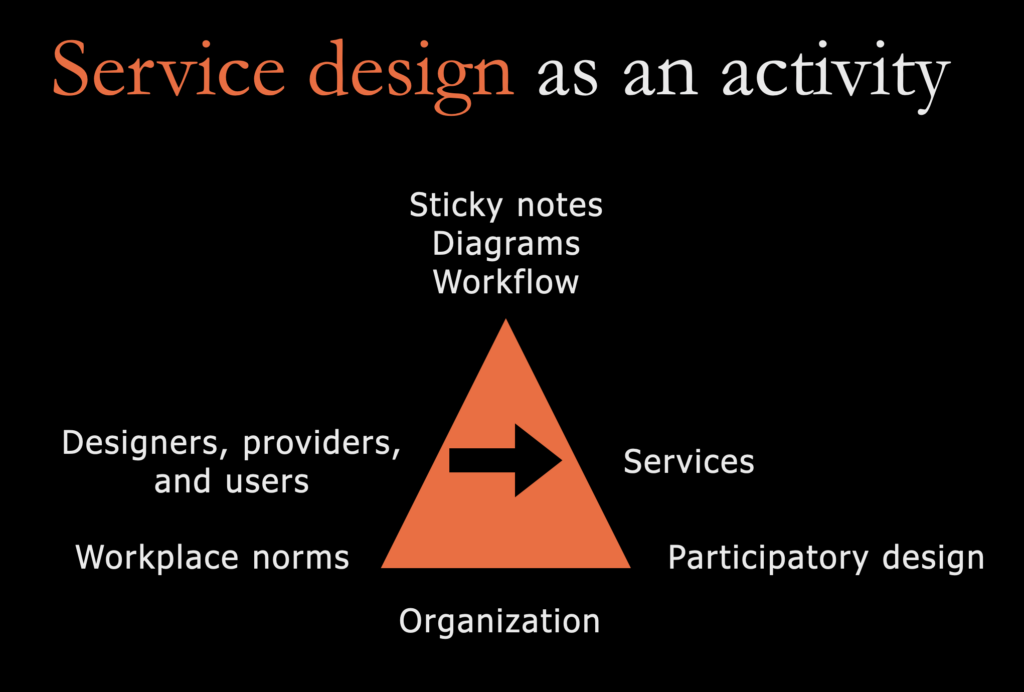

Service design has a different history. Service design is not just performed by professional designers; it’s also performed by providers, service providers, and users. Participatory design is a standard division of labor, meaning that these three groups join forces to design a service. The reason is that a service is not a product that can be delivered and transferred from one step to another in a production chain or factory line. You can’t produce a service through a factory line mindset or organization scheme. You need people caring for each other in human relationships. This is very important.

That’s how service design ties into management and service marketing. They bring in participatory design, and we use many instruments you’re familiar with, like sticky notes, diagrams, workflows, and messy visualizations. We read and discussed a paper this week that precisely compared how service design researchers use qualitative data analysis materials to make sense of users’ behaviors and activities and how different that was from, for example, product design.

Service design is closer to your experience here because our MXD program emphasizes co-design. We try to build on this tradition. We are not focused on services here, but it’s an area where co-design can be 100% applicable and generate incredible results for organizations and society at large. It does not make sense to do co-design in every project. You should know there are some things that, once you see them, make you say, “Hey, this is an interesting potential service design object.”

For example, a community may talk about a problem, and you may frame that as a service design object that needs to be redesigned with all service providers, users, and people responsible for delivering that service. What you’re going to do here is design research in general. You may find a service design object, but you may also see a graphic design object. The most important thing is understanding the design research process and the difference between design research and design activity. Design research aims to produce new knowledge. It’s not about producing designable objects like a service or visual communication.

Design research is similar to science. It’s closer to science than to design activity. That’s why it’s primarily practiced in academia, but some companies also do design research. One characteristic that makes it challenging to grapple with this field is that it connects many disciplines, like architecture, industrial design, and engineering. I’m always drawing on these fields because that’s the standard. Some people talk about the transdisciplinary nature of design research. I’m not so sure. I think some design research is pretty grounded in the traditional design fields like these three. I don’t believe that if you only deal with three disciplines, you are being transdisciplinary. In my view, transdisciplinarity means challenging disciplines and finding knowledge that’s not even part of disciplines.

I also have a pre-recorded lecture about transdisciplinary design that I gave last spring. These are all available on my website; you can watch them later if you’re a first-year. I don’t like repeating my lectures for second years, but if needed, you can watch the recordings and make sure that these are available. That’s why I’m recording this lecture right now.

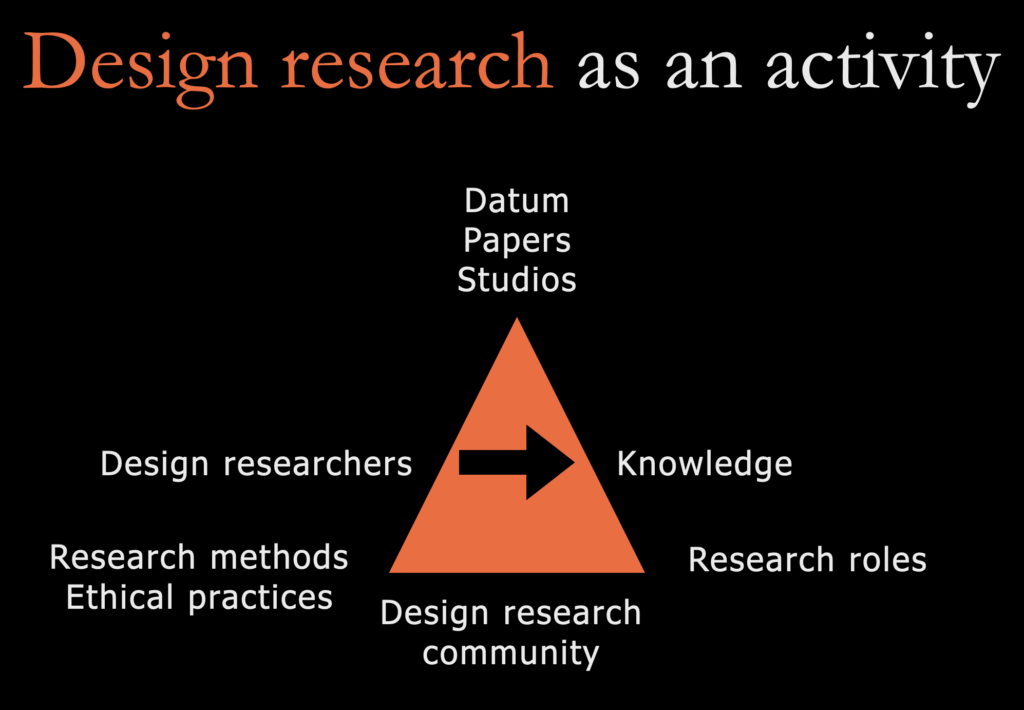

So now let’s return to the design research activity framed by the activity system model. First, you have design researchers modifying knowledge or producing knowledge, and they use data—“datum” being the plural form of data. They use papers, academic papers, scientific papers, and articles, and they use studios like we have here where we are now giving this lecture. However, we also have to abide by research methods and ethical practices. There are different research roles, like the researcher and the researched, or sometimes there’s no such differentiation. Sometimes you may say that your research is participatory and that everyone you engage with in your research becomes a researcher too, and they have a say, a stake, in deciding where your research goes.

Overall, we have the design research community, which holds conferences, and the best one I recommend you follow is the Design Research Society Conference, DRS for short, which happens every two years. DRS also has a lot of special interest groups or SIGs. One that I recommend you check out is the Pluriversal Design SIG, which is convened by many people, including my colleague Professor Maria Rogal. Together with Mariana Braga, I am proposing a new special interest group in social design. She is now working in the United Kingdom but she is also Brazilian. We are trying to bring back some old-fashioned revolutionary views on design in this SIG. You may also join our open discussions if you become an associate member of this society.

That’s what I mean by a design research community. People worldwide care about this activity, and we care first and foremost that design research is understood as something different from design activity. Many people overlook their distinctive objectives. Here is a quick comparison: Design research is concerned with knowledge. We may use designable objects as a means to get to knowledge. The tools of the trade are in design, whereas the scientific tools are in design research. We may adopt qualitative data analysis methods like grounded theory, but we will surely make grounded theory more creative and fun using LEGO Serious Play, for example, to convey emerging themes. That’s one of the things that Hien Phan is experimenting with in her research.

In general, design research is research-driven and discovery-driven. In contrast, design is more about applying existing things and not generating new knowledge, unless in the form or shape of new objects, because objects also embody knowledge. However, design research is about generalizable objective knowledge that can be explained through lectures, written in books, published in papers, and so on. Understanding design research, therefore, requires considering more than one kind of activity. So, you cannot just say that design research stands independently and ignores design activity. They interact.

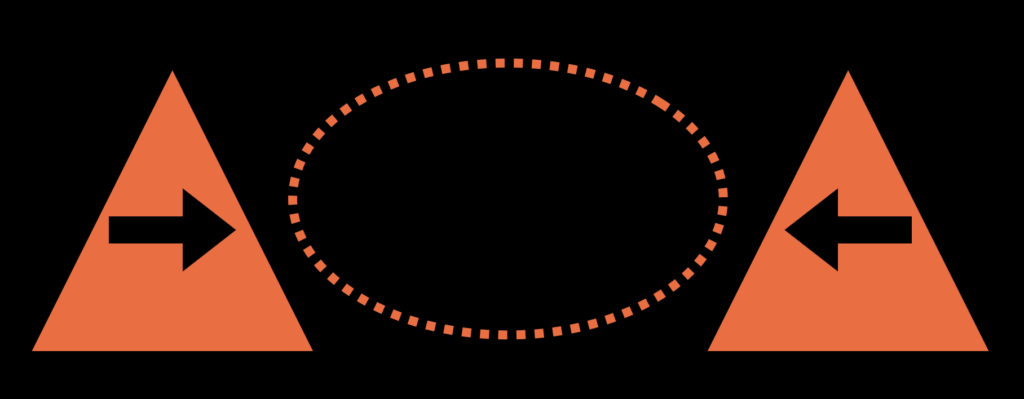

For that matter, I need another model from the activity theory framework. This is the interconnected activities model. I won’t use this one because you can connect activities in so many complex ways that will make the analysis very complex. I’m just saying this exists, and you can tell, for example, that the rule of an activity is an instrument for another activity. You can say that the object of one activity is to define the rules of another activity. For example, that’s what legislation does: legislation defines rules for other activities.

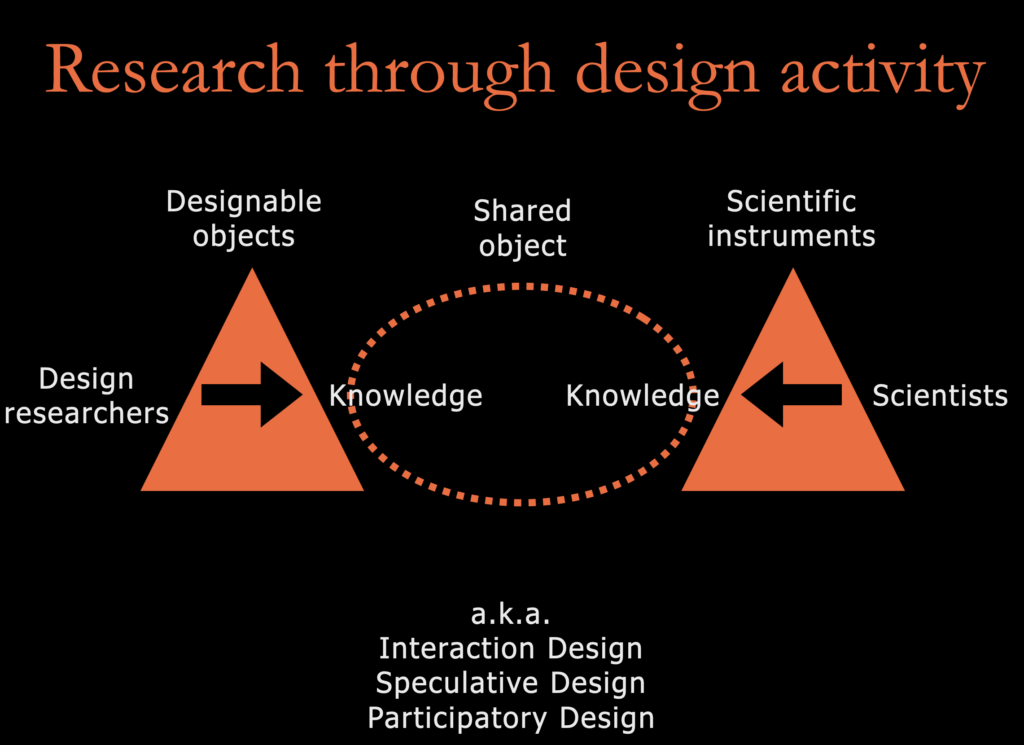

I will do something more straightforward: focusing on the most critical connection between activities, the shared object. When they converge and have common objectives, they almost function as if they were a single activity, but they are separate; they have different histories, and this connection may fade out at some point. There might be a split or breakdown at some point. So, the shared object is transient; it’s temporary. Again, all of these models I’m showing you stem from the work of Finnish scholar Yrjö Engeström, who works in education, organization, and learning. And that is an author Azadeh Jalali is reading as part of an individual study. So, if you want to know more about Yrjö Engeström’s work, you can talk to Azadeh.

Returning to design research and design research literature and applying that model, we can see that design research is an activity aimed at producing knowledge about, for, or through design activity. So, there are three possible connections between design research and design activity, according to Christopher Frayling, who wrote a historical article about these three different ways of doing research in design. We also discussed this article last spring, and you can also check out that article online and talk to your fellow second-years if you’re a first-year and curious about this.

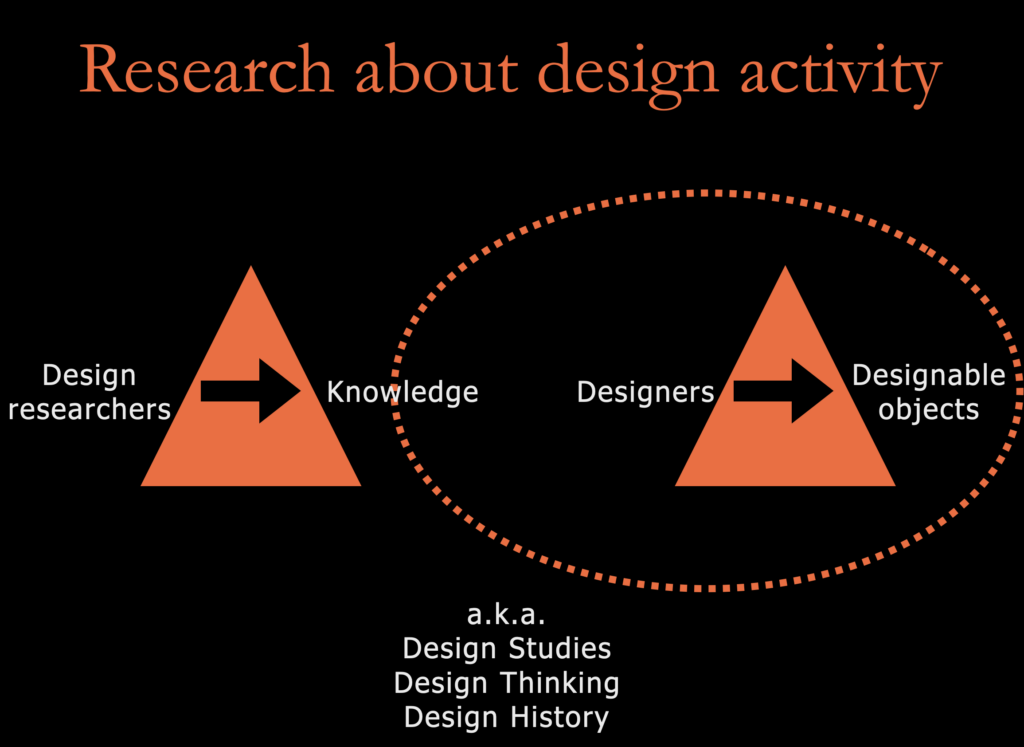

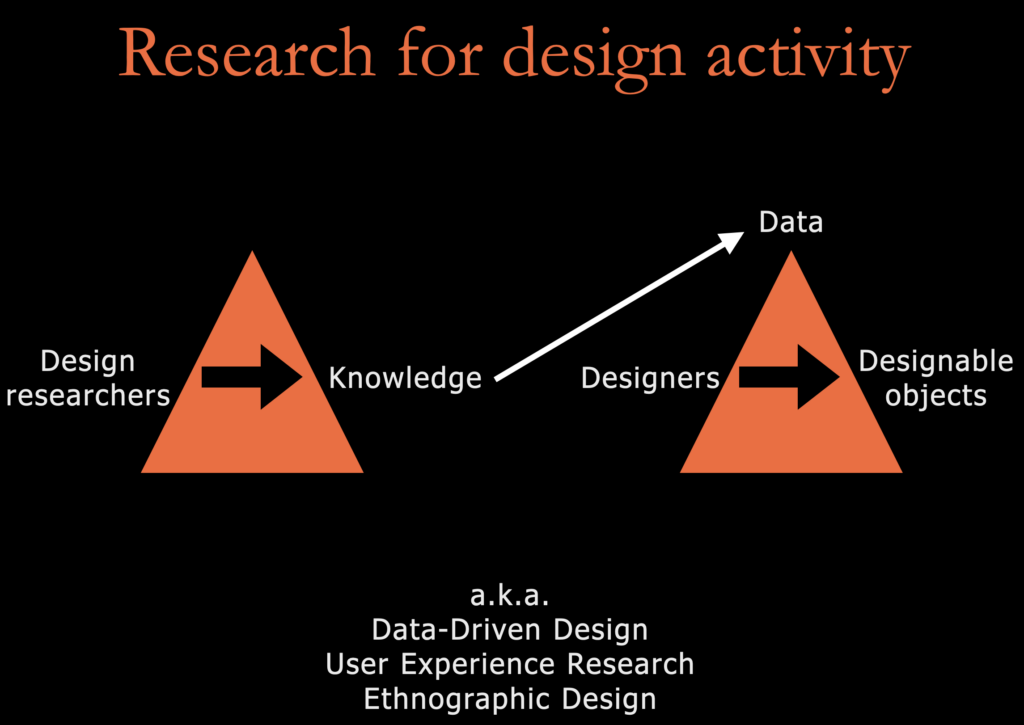

I’m going to go over the most critical aspects of this distinction because I’m going to apply this activity system model to convey and explain, perhaps even in a better way than Christopher Frayling did in his article, the difference between research through design, about design, and for design. Let me start with research about design activity, which is the easiest to understand. In this case, design researchers are producing knowledge about design activity, which is another activity, meaning that the object of design research is design activity. That’s why this bubble includes the whole design activity of designers designing designable objects. So, their connection is through a kind of distant view. Design research is taking a stand and making design activity more familiar so that you can research it.

Many design researchers are former designers, or they still move from one activity to the other. They commute physically or mentally. This is known in design research as design studies, design thinking, and design history. All of these sections in design research are researching the design activities of others. You may even conduct design research on your own activity; it’s possible, but it’s a bit odd. It’s hard to make that distinction if you are in both activities. What is most common in design research is research for design activity and also research in industry. If you see design research in industry, there is a high chance that it is research for design activity.

In this case, design researchers produce knowledge for another design activity, but that activity takes that knowledge as an instrument, rule, or maybe as a division of labor. Most of the time, it takes it as data. So, you basically do the research and you deliver the qualitative data analysis or the design data analysis. For example, all of these images that Hien Phan is producing with her MFA research, she could present this to the faculty body and say, “Hey, this is what I found after studying the MXD program, please fix it.” That’s a research for design activity. Then, we would have to redesign the program based on the data that she’s presenting to us. This is known as data-driven design or user experience research, ethnographic design, or design for innovation. There are many names for this, but basically, you have two different activities that are connected by one specific element.

Now, compare this to the shared model application of two different activities, and notice that now the second activity has its direction towards the same, converging with the design research at the center. Both of them are interested in producing knowledge. They may be of a different kind of nature, but it’s a shared object. The instruments may be different too, but they’re still trying to transform the same object. Design researchers use designable objects, and scientists use scientific instruments if they are collaborating to produce a shared object.

Let’s consider a possible research through design activity in which a physicist collaborates with an industrial designer to try out a new nanomaterial for making shoes that are biodegradable or shoes that have better resilience to weather and temperature changes. As a design researcher, you must design the shoes, try out the new model, but you also have to work with physicists to make it viable, to enable the features that you are seeking. That’s co-design. I didn’t include this in the list, but you can definitely see it there. It’s a scientific co-design in this case, or a multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, or transdisciplinary design. The most established fields that refer to research through design are interaction design, speculative design, and participatory design. They are all constructing something across different activities in society.

What you see here looks cool. You may say, “Hey, I want to do that!” because it conceptually matches what we do here in our program. But you should be aware that this does not happen automatically. You cannot simply make a shared object or say, “Hey, here’s my object. Do you want to share it?” No, it must happens from both sides. You have to expand your object here, and the other side has to expand the object there, and the shared object is where they meet.

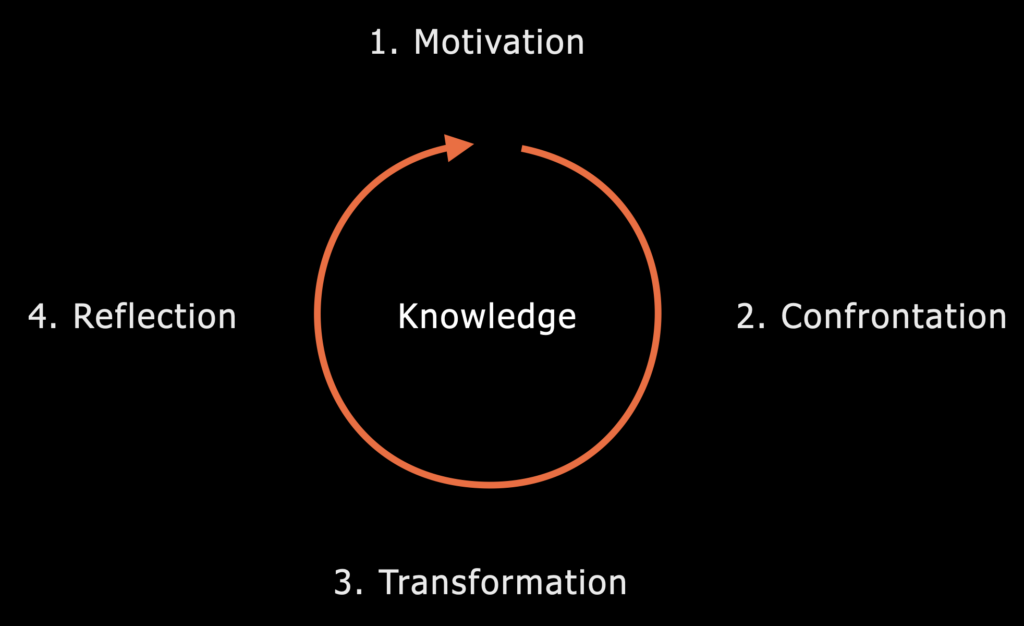

To track the expansion and transformation of the design research object, I devised this model here. It’s still a work in progress that I have to think about and develop further. But basically, what I’m saying is that a research object goes through at least four phases or moments in its life, and they are recurring moments: Motivation, when the object is motivating researchers and an activity to follow up and transform it; Confrontation, when the object is confronting reality, in this case knowledge being confronted with reality; Transformation, when this object is transforming itself, transforming knowledge in this case; and Reflection, when this object is being reflected within itself.

Let me illustrate how this model would unfold in my PhD project from 2011 to 2015. I know it’s a bit old but I have it documented extensively, and you can quickly find materials online about it. You could apply this to many other design research projects.

In the beginning of my project, it was all about healthcare facility design. My supervisors told me I had to produce knowledge about how architects, engineers, and healthcare experts design hospitals. That was my initial research context and goal, and that cycle went on in that phase. I’m going to describe some of these activities, some of the actions that happened there at that moment.

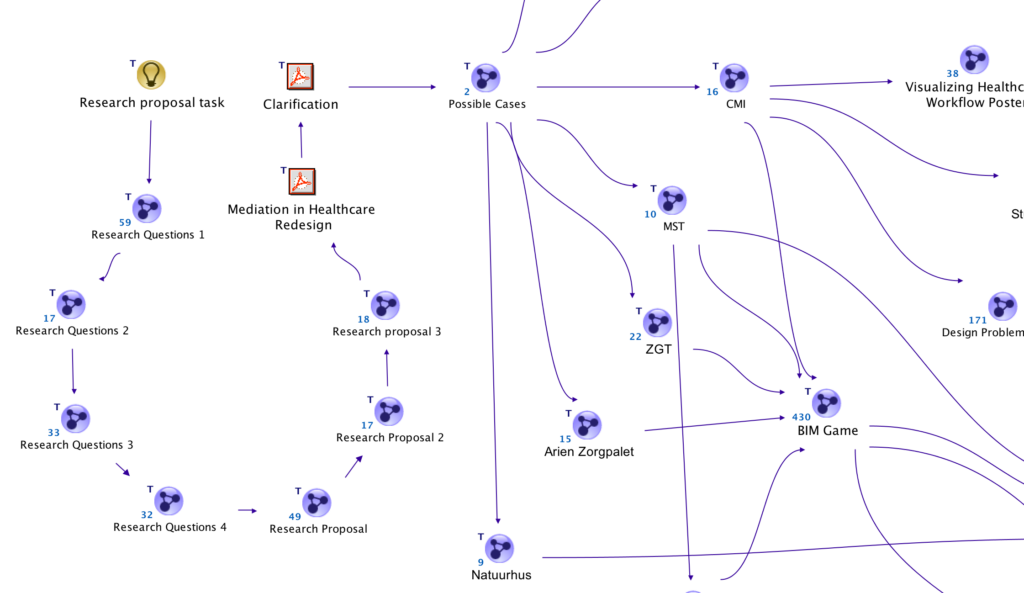

In motivation, typically you investigate your positionality, you disclose it, you look at the literature review, you write literature yourself, you formulate questions, you answer them, and you relate to data in a creative mode. You create data sources, you select them, and you use them. Here’s me trying to define what was going to be my research. In the first year of my PhD in the Netherlands, you had to deliver a research proposal. If that research proposal wasn’t approved in a kind of pre-defense, you would be fired by the university and that happened to one of my colleagues. It was quite common there. You had to deliver a very good, convincing research proposal, so I spent months on this. It was a big deal. Each one of those icons you see in this image is a clickable map that you can open and see many more icons, and you can see nested maps, one inside each other. That’s the basic environment for an issue-based information system, or IBIS. I’m using Compendium here, but there are other systems that support the same kind of, let’s say, supercharged mind maps. It’s not a mind map—it’s much more because it’s a mind map inside a mind map inside a mind map. You can navigate through it online.

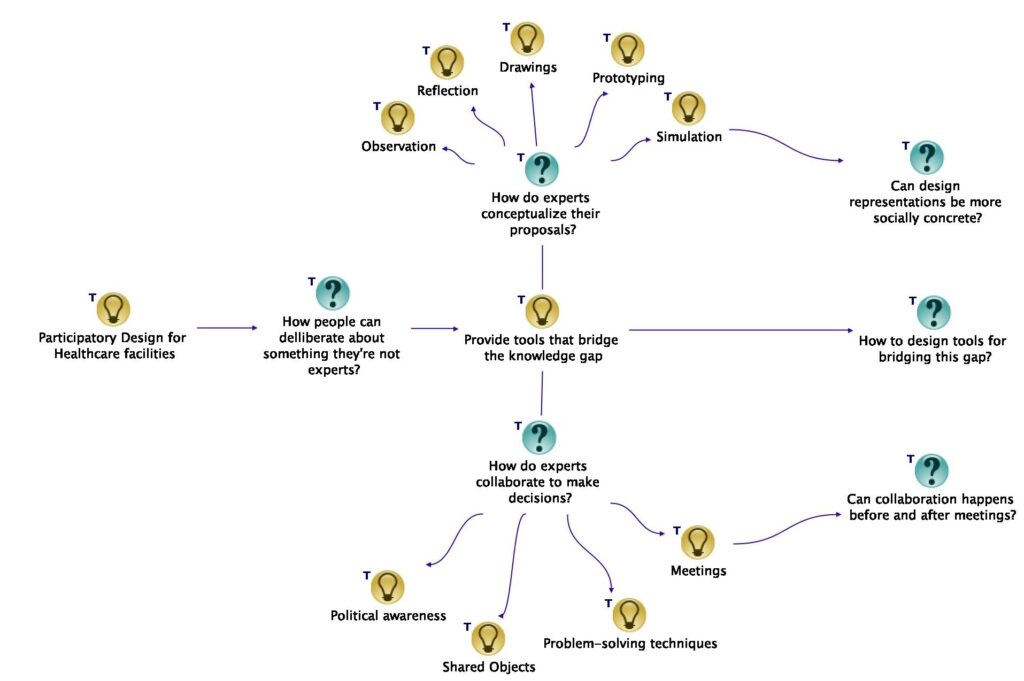

The goal here is to grasp consciousness, not just the mind. I just want to show you a little bit about how the research questions started to become more concrete over time as I revised them many times and showed them to other people, getting feedback, especially from my supervisors. IBIS has this notation where you can have icons that are question marks and icons for pros and cons. I didn’t use those in this map here, but I was basically concerned with three main questions: How can people deliberate about something they are not experts in, like patients and healthcare practitioners who are not architects or engineers? How do experts collaborate to make decisions? How do current engineers and architects design hospitals? How do experts conceptualize their proposals? And then, how can these proposals be more socially concrete? How can we design tools to bridge the gap between experts and non-experts? Can collaboration happen before and after meetings, not just in workshops like we do in participatory design? Those are the things that were on my mind at that time.

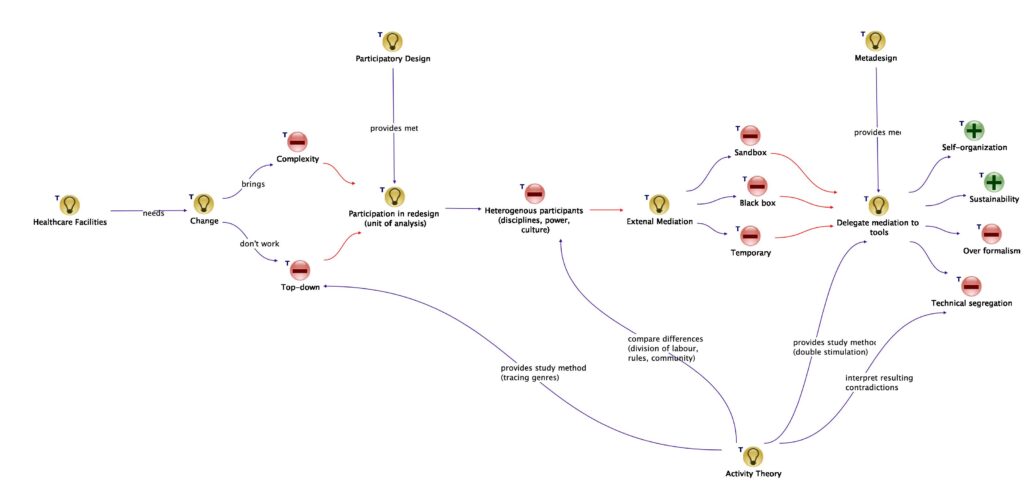

I revised them many times and moved from research questions to the full-blown research proposal. I had to make many maps, get feedback, and that was probably the last map I made visually until I got everything written down and submitted to the disciplinary council that would evaluate me. The context is that healthcare facilities need constant change; they have complexity, and it doesn’t work to change top-down. You need a theory that explains bottom-up processes, like activity theory, and that’s how I constructed the basic tenets of my research.

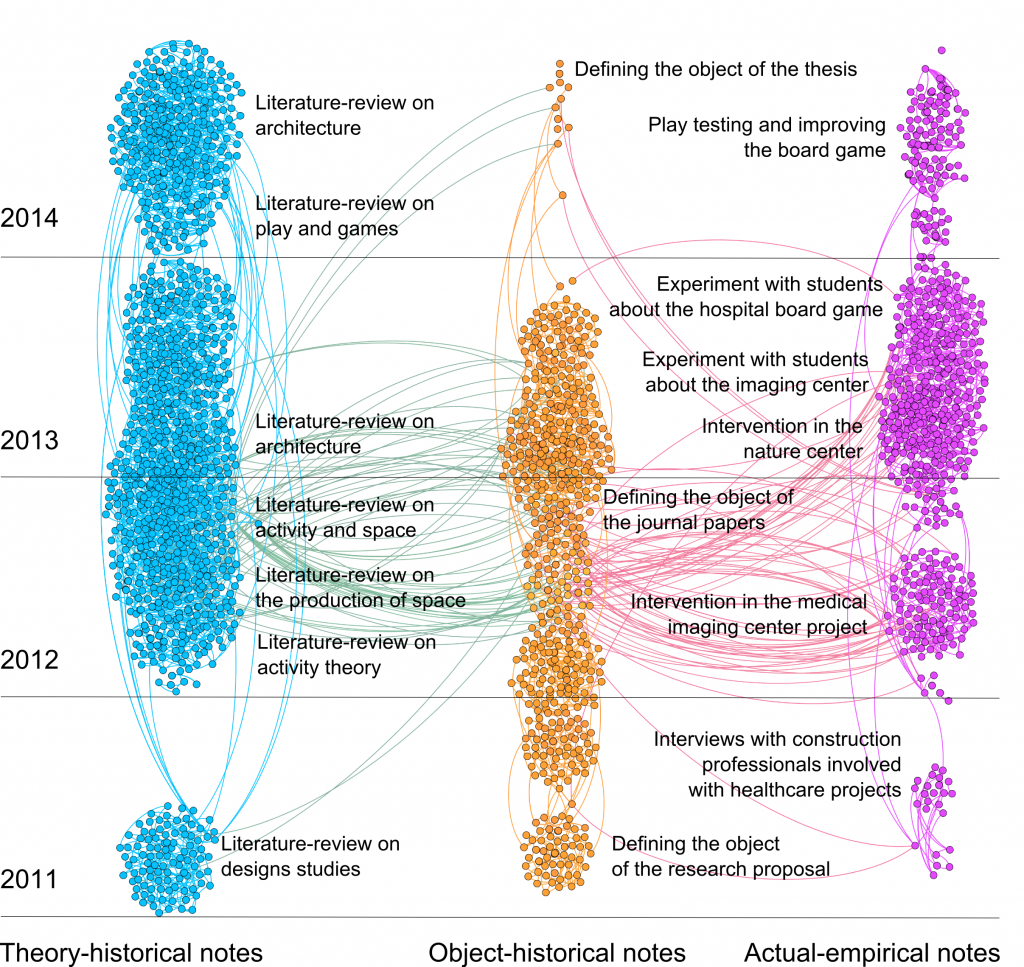

I was approved after quite some questioning from the disciplinary council—it was very hard to convince them. What I was doing was sound research, but I was very stressed out. The main reason is that in the first year, before I wrote my research proposal (which I finished between 2011 and 2012), you can see on the right side of this graph the notes I collected from field studies or visits to construction projects. A very few, if I compare to how many articles and papers I read and took notes on. At that moment, I was mostly writing research questions. Each one of those research questions you saw on the last slide is one dot in this visualization. This visualization is not so much about content; it’s trying to convey the rhythm of my research activity and the concentration points. I started focusing pretty much on reading and then moved towards doing some field studies—just some brief interviews, attending conferences, talking to people who work as engineers, architects, and so on. Then I spent a lot of time defining my research, doing the research proposal, and so on.

You see that at this moment, I was stuck in this threshold of evaluation. Once I got my green light, then I start to delve a lot into each of these tracks, making a lot of connections between them, which makes my research construct stronger and stronger. I had to confront all of these ideas, and as soon as I could, I got into field studies.

You could do participant, bystander, or self-observation field studies, but the most important thing is that you follow processes as they unfold. That’s the moment when you do data collection. So, here’s myself visiting some construction sites together with Vedran Zerjav, a colleague who was doing a post-doc there and also studying collaborative design. We observed many collaborative design meetings like this one, in which they were evaluating a future diagnosing center from the operational logistics perspective. I recorded many of these meetings and interviews using multiple cameras and even an iPad. And of course, I analyzed it, but that’s not in the confrontation phase. While I was in the field, I was also designing new things, meaning transformation. I was trying to transform the object of my research and was creating opportunities for more people to design with or to foster participatory design in construction, particularly in healthcare and hospital design.

Most of these projects already existed, so I had to convince people to open up a little bit for participation, which is something hard if people don’t start the project from the ground up believing this is important. In the Netherlands, that’s not so difficult because they do have a quite ingrained democratic culture, at least in the workplace. They call it “overleg kultur” or “polder model,” meaning that they like having long discussions and having everyone sit at the table to decide what to do. It’s part of horizontal less-hierarchical structures.

That’s the moment when you do something very unique to design research, which is data generation. Most of the time, in qualitative data analysis, they won’t talk about this phase because typically, social scientists don’t generate their data—they just observe data being generated by others. Like, you observe someone on the street walking, and then that data has been generated by the people on the street. But in this case, it’s a bit different because design research can design an experiment, so you can create a mechanism for generating observable data. You give a tool, you give a game, where the outcome of their thoughts and conversations become visualized. And then you can record it and take pictures. So that becomes an interesting piece of data for you.

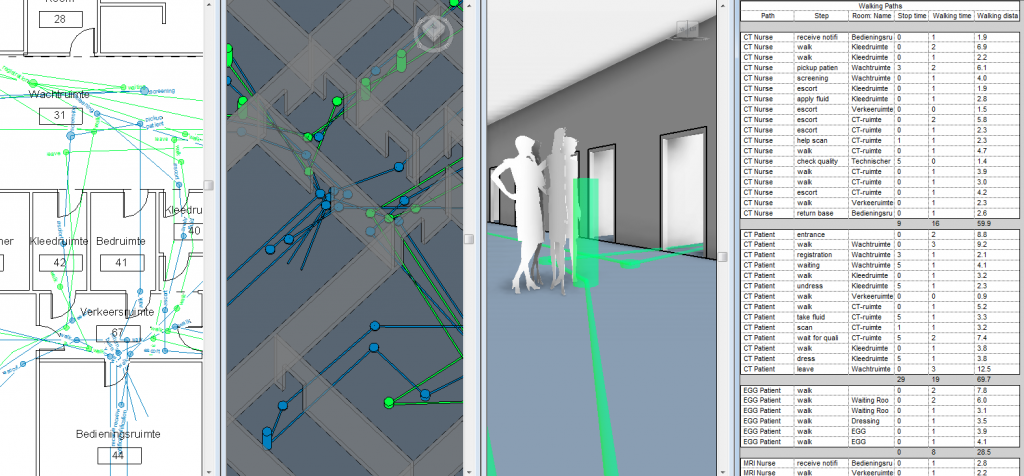

The first tool we used in that project was simulating healthcare procedures using a professional healthcare simulator called Flexsim. We interviewed many people, we asked what kind of diagnostic machines would exist in this center, and then we built it in this virtual system—how many people would come in, how much time they would spend in each part of this facility, where they would walk, the pathways. We could calculate: if we get this many patients, we could treat this many patients by the end of one day. And we would need this many healthcare professionals to care for them. It was kind of calculating the maximum capacity or throughput of this diagnostic center. When we showed the model to the healthcare practitioners, nobody understood it—it looked fancy, but they could not understand the reasoning behind it. They said, “We need to understand exactly the rules behind this model.” And as soon as we opened the software black box and showed the configuration system, they were put off by it. They couldn’t follow because it was overly complex. Only us engineers could understand it.

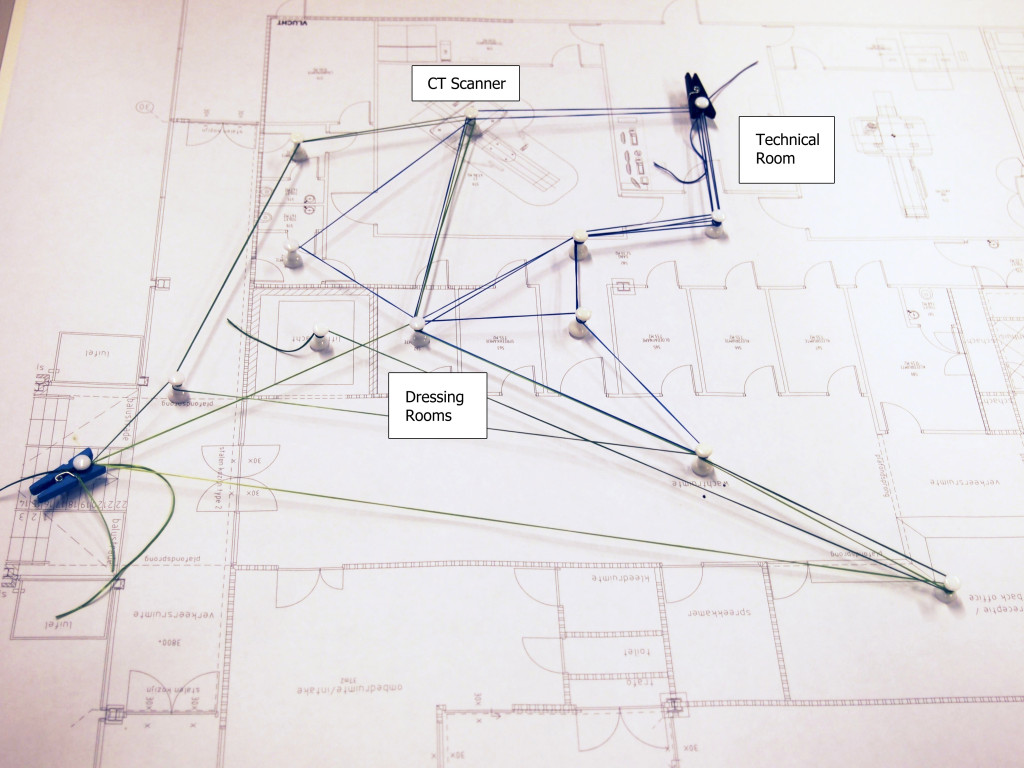

Therefore, we decided to try a low-tech tool, something that would be much more tangible and could be understood just by looking at it, interacting, and playing out—more pliable, more like a game. And that’s the origins of the famous knitting game. I was inspired by how people knit textiles, and I was looking at how they talked about these walking paths and how the workflow of nurses had to, at some point, match the workflow of patients moving through the facility. They had to be in the same place at the same time.

You basically lay down the paths as pieces of thread, and each stopping point is represented by these pins. You wrap around them, and then you can see, by the different colors, how different paths of different roles in that activity unfold through time. This was a major innovation in the process. We brought it back to the project after trying it out ourselves, and stakeholders were delighted. They had a great discussion using the knitting game, and that led to my first journal paper, which was accepted before my PhD defense and enabled me to actually go to the defense because that was a requirement.

Then the last phase, the last moment of the design research object, is the reflection phase, when the object is trying to figure out what it is using you as a researcher. You identify patterns, generalize findings, and increase levels of abstraction and universality. That’s the moment where you do general data analysis. I analyzed my data after every step in the process using the IBIS system I mentioned to you before. Here’s just a small chunk of data analysis I’m doing from that workshop where we used the knitting game. They were talking about radiation at the parking place, some kind of system that would have a strong impact on its environment. It had to have a safe area around it, maybe some different kind of construction materials, and that had an impact on the elevator they were planning to construct. Nobody had figured this out because the people who knew about this machine’s impact on the environment were not the architects and engineers. They were just healthcare specialists, and they did not mention it because nobody asked them. This would have generated a construction problem that would be very hard to fix later on.

I theorized my findings using the same IBIS. After I documented what happened, I tried to explain why things happened this way, then I applied activity theory and production of space theory, which I’m not going to explain here, but I was really trying to find contradictions in all of that. After identifying those contradictions, I could look back at the practical aspect of this research and discovered that I could generalize from a low-tech to a high-tech approach to visualization. This is something very much needed in architecture and construction. Not many people do that—they usually go straight to high-tech and miss the opportunity of having this more sensitive, human way of looking at data and understanding its underlying reasoning. So, you do the knitting game first, and then you can input all the data you’ve collected with the knitting game into a virtual reality or, let’s say, building information modeling (BIM) 3D system that matched visually the knitting game on purpose. Then you can design the evidence, test it out on current spatial layouts for a building according to potential walking paths or people’s workflow.

That’s not something that architects do that much. They sometimes do spaghetti diagrams, but that’s not so normal. They usually talk about occupation in a very general way. At least, that’s how they did it there where I studied. They would say, “This is the floor plan. What would you do here?” People answered “I don’t know”. People don’t get to that level of detail about knowing the activity because they don’t consider it their business. That results in many problems, in terms of contradictions when trying to make space fit activity.

I tried out my activity walking paths system in a technology conference. I had this interactive whiteboard running the software, and I started to notice at that time that my research object was not moving in the linear fashion I just presented to you. It was moving in a much more chaotic way. I just presented it this way so you could grasp the whole overall picture. Now, I’m going to be more chaotic and more realistic too.

At some point in my research, a new funder came in, BIM Werkplaats Twente, and they expected a serious game about building information modeling, Autodesk Revit, and other similar tools. Revit helps with the design and quality of buildings across different disciplines, so you can integrate multidisciplinary design into one single digital model. This is the facade model, this is the structural model, and that last one is the infrastructure model, for example, where the heating and cooling systems would go through. They could all be designed separately on different machines, and the Revit system would integrate data from multiple models so that construction workers or designers could find interference or contradictions—for example, a pipe running through a door. If one person is designing where the doors should go and another person is designing the pipes, these things may happen: pipes going through a door, which should be prevented before you start constructing. That’s the main advantage of using building information modeling, and that technology was new at that time, so they wanted a serious game to promote it. However, I didn’t want to promote it; I wanted to feature contradictions.

My research shifted from being about design activity and hospital design to being about another design activity, which is complex construction. That’s how it used to be, as I showed before, and that’s how it became something else. The activity was complex construction projects. I no longer needed to focus on hospital design, but I decided to design a board game called The Expansive Hospital, using the hospital as just an example of a multidisciplinary, complex construction project where BIM would make a difference—sometimes for the better, sometimes for the worse.

What happened is that there was a reduction here. It was an reductive moment in my research history, where my research object shifted from being about human aspects to becoming much more technical. Alright, I accepted the condition because it was a funding situation—if you’re funded to do something and you don’t do it, then you lose your funding, right? You can’t avoid that.

I started playing many board games and digital games related to my task, like Theme Hospital. Does anyone have experience playing that? No? It’s an old-fashioned hospital simulation game. It’s very fun because it has strange diseases like a person who is invisible. On the right side, you can see you have to treat that person to help them return to normal. It’s a lot of fun, but you see the impact of a hospital layout on patient experience. On the left side, you see 1830; it’s a very complex railroad design game. I learned a lot about capitalism playing this game. It took me 18 hours to go through the entire process, divided over three days, and I gained an understanding of how, for example, shares work in open markets and brokers’ roles in construction projects.

What I learned from these two games is that you could represent something very complex through a board game. A board game enables you to represent contradictions in a very engaging, fun, yet still complex way—complex enough to be considered scientific. I attended board game fairs in Essen and other places in the Netherlands. This is the biggest one in the world, I suppose, and there were, I don’t know, thousands of people. It’s a really big thing in Germany and other German-influenced countries like the Netherlands. During wintertime, people spend a lot of time playing games indoors, and I would say it’s also popular among people who don’t like staying in front of the television or a smartphone most of the day. People want to see other people, and therefore they play board games.

Now, you’re going to see I’m moving quickly through these different moments, and I’m going to use this bubble here to follow which kind of phase I’m in, but the most important thing is to understand that it’s chaotic and very unpredictable. I created nine prototypes of my build-a-hospital game, each time trying out different materials I could find at a local office supply or toy store. Every time I playtested the game with different people, I changed the game and improved its design to better express the contradictions and underlying issues I found in my field studies. This game was supposed to convey real scientific data in a fun, engaging way so that people would not need to read a paper to understand my research.

Each time I playtested it, I included the qualitative data I collected through my notes or recordings in the IBIS again. As you can see, IBIS played a central role in my whole PhD trajectory and still does—I still use the same IBIS today. At some point, I used the board game to start transforming reality, so I brought it back to BIM Werkplaats. I was a bit afraid because this game wasn’t apologetic. It wasn’t saying that BIM had only advantages. The game also showed that the person who holds all the information in the system—in this game, the building information system is just a sheet of paper with data in those corners you can see on this sheet—would gain so much power that they could use it as leverage in any negotiation, sometimes even for blackmailing other players. It was common for people to hide their information sheets from others to use their privileged access as an advantage in negotiation.

This game revealed that BIM had a negative side to collaboration. It wasn’t a 100% beneficial system for enabling collaboration in the perfect, utopian world that Autodesk Revit wanted to sell. Dutch people are quite open to change if you present them with a contradiction, so you can definitely have a serious conversation about how to be more critical when using Autodesk Revit. That’s what people took away from this playtesting session, and that was a moment of confrontation—confronting the knowledge I had about the construction sector with the reality experienced by seasoned practitioners.

After testing that game with construction management and engineering students, I developed a visual method for finding shared objects and spaces around them. I can’t tell you much more about this now. I just want to point out another paper that came out of this after my PhD defense, and that was a moment of reflection, theorizing, and generalizing my findings. The Expensive Hospital was featured in the Dutch Design Week exhibition in 2014, one of the most important European outlets for design work. It was considered a design object besides being a design research artifact. I didn’t present my research process there; I really had a product that anyone could understand, even kids. That was the most interesting aspect of this exhibition—having kids understand my PhD research. That was very fulfilling.

After validating the game for hospital design, I started playtesting it with people with no construction background, still in the Netherlands. Soon, I defended my thesis in 2015, but I still kept the object within me. I felt like this was bothering me; I wanted to continue researching that topic, and I found new motivation when I returned to Brazil. That was the moment when the object started to expand again. I recovered some things that I missed in my PhD, some lost threads I could pick up. So, I returned to a hospital, and in that hospital, I playtested the game during a major organizational change process. The practitioners—mostly nurses, doctors, and managers, with no engineers or architects present—were so excited to see their reality represented there. They said, “Wow, can’t we use this game to redesign our activities here?” And I said, “No, because this game is just representing activities in a very broad way. If we want to dig deeper, we need another set of open-ended, flexible games, like gamestorming.” Pretty much like we do here in this studio all the time.

The Blind Side game on that wall, with unknown unknowns, is one example of a gamestorming activity. We didn’t use it in this project, but we used many others. I facilitated and observed several of these sessions, and I was surprised to see that they became motivated to tackle the contradictions that really prevented them from further expanding their healthcare activities and improving patient care. This is an overview of the games we played; some were custom-tailored, and some were drawn from that famous gamestorming book.

At that moment, I understood that expansive design was definitely a transformational approach to design research, and transforming the organization was its main outcome. So, the objects started to become shared again with these healthcare practitioners. Again, this did not happen automatically—they were seeking something I could offer, and I was seeking something they could offer. That’s why this collaboration worked so well; we had a shared object. I was concerned with producing knowledge, and they were concerned with patients. Through these serious and design games, we could both learn more about healthcare activity.

When I used serious games, I was validating my research; I was in my activity. When they used design games like gamestorming, they were in their activity, and that transition was enabled by this shared object, shared language, and shared space. After that, I reflected and started to compile a generalized, gamified organizational change or service design process. I didn’t have many other cases to apply this to in healthcare, unfortunately, but I could apply it, transform it, and expand it even further to other organizations of a different nature. For example, in this utility company’s Open Innovation transition project, they wanted to promote more open innovation in their organization. We played many of these gamestorming activities to find underlying contradictions and use that as a force—or let’s put it another way, as a power—to change the entire energy sector to become more distributed, based on several actors connected by a smart grid.

I started to notice the transdisciplinary characteristic of my research object, which cut across several disciplinary activities. It wasn’t just about hospital architecture any longer, or even healthcare service design; it was more about transdisciplinary design. Expansive design expanded beyond its initial healthcare context when Yrjö Engeström first proposed its concept. I built on that concept; I didn’t invent expansive design, but in my hands, it became a general practice of attracting expansive design research objects.

Here is Hien Phan‘s MFA research again, and Hien is trying to grasp her research object. What she doesn’t know at the beginning is that it’s not like she’s trying to find the object; the object is actually finding her through those models. Those LEGO Serious Play models were representations of her surrounding reality, but the reality was there, poking at Hien and, of course, each one of you who share the same context and have something to do with diversity and its contradictions here in the United States. You’re part of this contradiction, and that only became clear to Hien after she modeled many times her situation as an immigrant design researcher of Vietnamese origins studying and working in the United States.

This is going to be considered an example of expansive design because by trying to open up the design research activity to incoming research objects, the design research activity is changing every time. In this practice, the design research object is not an abstract matter that can be known beforehand, produced by a method, and defined by clever research proposal writing. So, I don’t believe in any of these things, although sometimes as director of graduate studies, I need to request you to fill out those forms. But I believe this is just a formality; the most important thing is the concrete experience. I even wrote about this in my PhD thesis preface—at that time, it was a half-baked concept, so I wrote: “When people asked me for definitions at the early stage of my research, I could only provide them with a discussion on definitions. For example, I said, if you define something, it’s because you already know what it is, and hence there is no need for research. Research is always about something that you don’t know.” By saying that, I skipped defining what I was researching and legitimized an exploratory approach for research. Of course, not many people liked that, but that’s how I approached it.

Eight years after that, I can firmly state that the design research object defines the design researcher, not the other way around. That changes everything in the way we start a design research project, because that means you don’t start it. It’s already there—you just need to find it, you just need to actually be found, to be conscious of the object in front of you. The thing is bothering you already, and you may not have been paying attention to it. Design research has an opportunity to make that more conscious, and you can transform that design research object either against it or in the same direction it’s already going.

Every design research objects, and now I take the etymology of the word “object” seriously, is an objection to the current world. Every object, for example, if I say this object—this table—nobody pays attention to the entire room anymore. I detach this table from the entire room, and it becomes an object of my perception, an object of my speech. But as soon as I stop talking about the table, the table fades back into the world. An object is something that is bothering people because it’s detaching from the world and saying, “Hey, I need to be changed.” It is a problem to be solved in design research language, and it demands us to position ourselves in relation to it. We cannot remain indifferent to design research objects.

But here’s the catch. When an object motivates me enough to investigate it in depth, it is because I am part of the world needing change. If I join an object’s objection, I stand against that part of the world that needs changing, meaning I stand against myself. So, I need to change. That is a very important insight I learned from Álvaro Vieira Pinto and his very interesting philosophy of subjectivity and objectivity intertwined. Henceforth, my existence as a design researcher is being as well as becoming with the world, not just being in the world as philosopher Heidegger posited before and that many people have built ontological design and even pluriversal design on top of those ideas. I believe that being with the world is something completely different because the world is changing as much as we are.

In simple terms, all of that means that at some point in the life of a design research object, the design researcher must become the design research object. You must make yourself part of your research. And to remain authentic to the spirit I embody—with that, I mean I am very inspired by the Phenomenology of Spirit by Georg Hegel—I need to consider myself as part of the problem and its solution. I need to object to the objects that object me from within myself. I need to find their contradictions as part of my being. I need to see that not only as an objective matter but also as a subjective phenomenon. And I have to see that object as impacting my collective existence, putting that existence at stake. And when I say collective, I mean people like me and people unlike me—people who share some spaces or history that can be endangered by those research objects.

So, in the next slide, I am going to share the current research objects that bother me, that put my existence at stake:

- systemic oppression,

- far-right extremism,

- climate racism,

- digital colonialism.

If you are going to approach me to share your research, you should know that these are the objects I am mostly concerned with. You should have a research object that has a connection to those; otherwise, I might not be the best person to help you with that. However, everything I said so far works for any kind of other design research object, right? This is just my personal situation right now.

In sum, if you haven’t found a design research object yet, look around for the objects that already object to your collective existence. Objects that are bothering people like you. Maybe they are not bothering you individually as much, but if you look collectively, think about what kind of person you are and what you are in relation to what is being used—what this object maybe doesn’t want to be. Anyway, the object is definitely a contradiction in this perspective.

That contradiction can be, as I mentioned, climate racism. For example, you can be very afraid of hurricanes—that’s something common here in Florida—but you may be worried because you may have to pay higher property prices or higher rent because of the hurricanes. Even if your property is not damaged, the property being damaged on the coast impacts property prices throughout Florida due to how insurance is now funded by the government. Once you start to learn this, you see that, well, yeah, climate racism really does exist.

Basically, the privileged white people who can afford houses on the coast have their insurance paid by non-white people who live inland, have lower incomes, but pay property taxes that fund the insurance for those coastal properties. White people couldn’t afford insurance themselves just because insurance costs went so high due to climate change. It’s very complex, but then you start to realize that my existence is put at stake buy this. I didn’t know and I didn’t chose all of this. I just knew that I was paying a ridiculous amount of rent, and one of the reasons is that housing prices need to be high for the state to earn more from taxes, as they don’t charge income tax but do charge a significant amount in property taxes, which is, of course, converted into the rent I pay.

Alright folks, what can design research do to transform these objects? I don’t know; it’s up to you. That’s your call, at least for those who are going to work with me further. Thank you.

References

Engeström, Y. ([1987]2015). Learning by expanding. Cambridge University Press.

Yrjö Engeström (2001) Expansive Learning at Work: Toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization, Journal of Education and Work, 14:1, 133-156, DOI: 10.1080/13639080020028747

Frayling, C. (1994). Research in art and design (Royal College of Art Research Papers, vol 1, no 1, 1993/4).

Van Amstel, Frederick M.C. (2015) Expansive design: designing with contradictions. Doctoral thesis, University of Twente. https://doi.org/10.3990/1.9789462331846

Van Amstel, F. M.C., Zerjav, V., Hartmann, T., van der Voort, M. C., & Dewulf, G. P. (2015). Expanding the representation of user activities. Building Research & Information, 43(2), 1-16. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2014.932621

Amstel, F. M.C. van; Zerjav, V; Hartmann, T; Dewulf, G.P.M.R; Voort, M.C. van der. 2016. Expensive or expansive? Learning the value of boundary crossing in design projects. Engineering Project Organization Journal, 6 (1), Pages 15-29. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/21573727.2015.1117974

Engeström, Y. (2006). Activity theory and expansive design. In: Bagnara, S., & Smith, G. C. (Eds). Theories and practice of interaction design, 3-23.

Pinto, Á. V. (1969). Ciência e existência problemas filosóficos da pesquisa científica. Editora Paz e Terra.

Heidegger, M. (1962). Heidegger, Being and Time. Harper and Row Publishers.

Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich: (2018) The Phenomenology of Spirit. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Translated by Terry Pinkard.