Abstract: Designing from the positionality of a user instead of the designer’s is a must for designing against oppression. By acknowledging oneself as both a user and a worker, this approach dismantles patriarchal, capitalist, and colonialists paradigms that separates managers from workers, and designers from users. Born out of self-management, this approach thrives on collaboration, open-source tools, and community-driven economies, creating solutions rooted in transparency, mutual accountability, and cultural authenticity. Designing as a user is a step forward in overcoming the trap of user-centered design beyond what participatory design has already done.

This lecture was recorded in the Spring 2025 Research and Practice MXD MFA course at the University of Florida.

Video

Audio

Full transcript

Today’s topic is designing as a user, and it’s the second part of my last lecture on self-management and the self-managed studio. At the very end, I provoked you to think about your role in self-management. You cannot approach self-management as a boss, nor can you come to self-management as the expert designer who designs for others.

In this presentation, I’ll share some insights from my own experience of joining self-managed collectives, beyond the self-managed studio, as a user. You can also design as a user and step away a little from the role of the designer—the one who knows how to design things in relation to others who don’t.

Before we get into that specific content, I want to recall and connect back to other streams of thought that are gaining prominence in design research. The concept of positionality is closely related to this. When we talk about positionality, we draw from feminist cultural studies. In those writings, authors argue that if you’re going to do qualitative research, you must evaluate whether your biases are contaminating or distorting your data. One way to approach this is to disclose your bias through the concept of positionality.

Positionality is essentially a resource for researchers to disclose and reflect on the social and historical positions of their human body, including ancestry, gender, race, class, ethnicity, body condition, and handiness. I’ll talk about handiness later, as it’s typically neglected in discussions of positionality, particularly in social sciences and, even more so, in design research. This neglect creates a gap that prevents us from seeing ourselves as users and recognizing that being a user is, in itself, a position too.

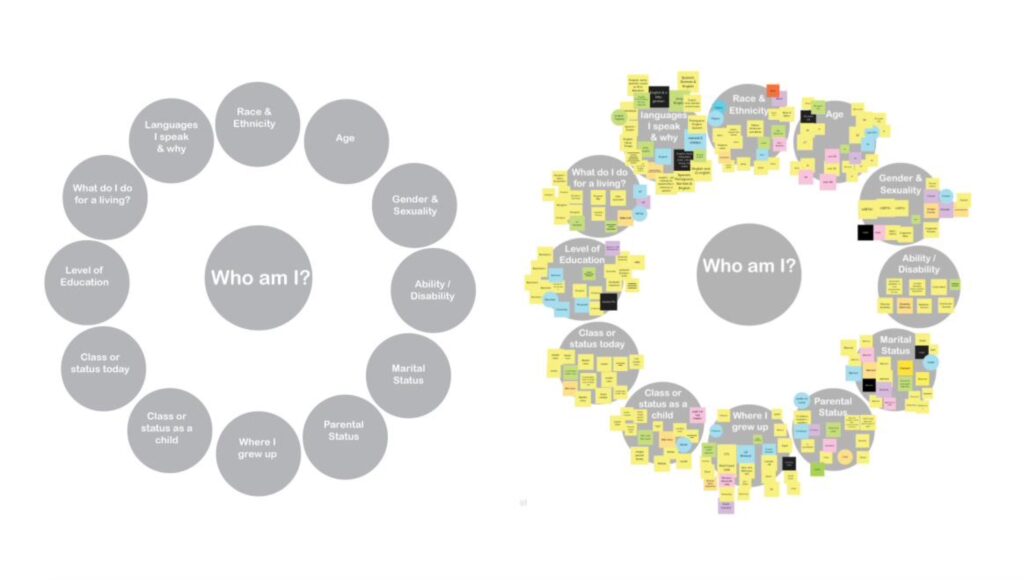

The person most prominently advancing this concept in design research is Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel. Dr. Noel has been vocal about the importance of knowing yourself while designing for other people and when designing with other people. She developed a tool called the positionality wheel to discuss, analyze, and compare different positionalities.

You can print it out and work on a sheet of paper with Lego pieces on top, as we typically do here in the MXD studio, but she devised it during the pandemic for online, Miro-based co-design workshops. In this example, you answer questions that reveal shared positionalities. If people respond similarly, they share positionalities; if they respond differently, their positionalities differ. Questions range from gender or sexual orientation to age and upbringing, and they can be customized based on the positions you want to explore, share, and compare.

Lesley-Ann Noel explains this approach in her book Design Social Change, published last year as part of the Stanford D.School Guide series. I highly recommend this book—it’s a short introduction to the kind of work we do here. She’s also a scholar who builds on the work of Paulo Freire, bell hooks, and other critical pedagogy authors.

In that book, she introduces a new concept that complements positionality: oppositionality. Noel emphasizes that once we realize our position in the world and our relationships with others, we will inevitably recognize that we are against something that threatens or undermines one of these positions. For example, if you are a Black person, your positionality implies being against racism—that’s your oppositionality. However, there are instances where people don’t adopt the expected oppositionality. For example, a Black person who isn’t opposed to racism or even perpetuates it. Similarly, there are sexist women, ableist individuals with disabilities, or anti-Indigenous natives. This often happens when people are confused about their positionalities—they’re unsure of who they are.

Lesley-Ann Noel seeks to help us reflect on this so we don’t end up in counterproductive positionalities. A productive positionality means knowing what you are against. It involves an explicit reading of the world from an oppressed positionality and positioning yourself against oppressive features of the world that must change. Design Social Change is fundamentally a book about designing against oppressive structures in the world.

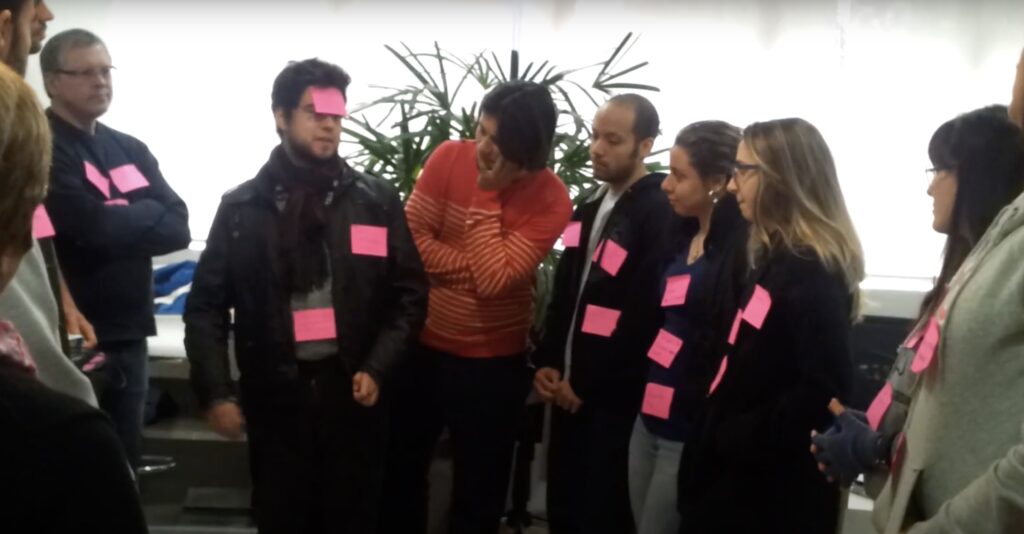

As much as I appreciate Noel’s work, I approach positionality differently. For instance, last year, we created self-portraits using trash as a way to discuss positionality instead of using the wheel or any other classificatory system. I also use constructive tools for exploring oppositionality, one of which I adapted from the Theater of the Oppressed. It’s called What Am I, What Do I Want? It’s a dramatic game where participants state out loud, “What am I? What do I want?” I added a third question: “What prevents me from becoming or doing what I want?” Participants write their answers on post-its and attach them to their bodies where it feels most relevant.

For example, one participant wrote their answer to “What am I?” and placed it on their forehead, probably because they work in a brain-intensive profession like programming. These reflections allow participants to recognize both what they oppose and what they support. There’s always a positionality implied in oppositionality and vice versa. Being aware of both is crucial. By becoming aware of positionality and oppositionality, you develop what Paulo Freire, Álvaro Vieira Pinto, and Lesley-Ann Noel call critical consciousness—knowing yourself, identifying what to oppose, and acting in your best interests.

It sounds great and fair, but we live in a society that cultivates naive consciousness—a concept developed by Álvaro Vieira Pinto. This lesser-known concept is essentially the opposite of critical consciousness. While many are familiar with critical consciousness, few understand naive consciousness, which Vieira Pinto examines in his 700-page book Consciência e Realidade Nacional. This book offers a detailed analysis of how naive consciousness manifested in Brazilian society in the 1960s. In 2022, I taught a course on this book in Brazil, where my students and I analyzed how many characteristics of 1960s naive consciousness persisted in 2022. We found these traits alive and well, particularly among supporters of Brazil’s far-right movement, which attempted to maintain control but failed when Bolsonaro, their far-right candidate, lost the election that year.

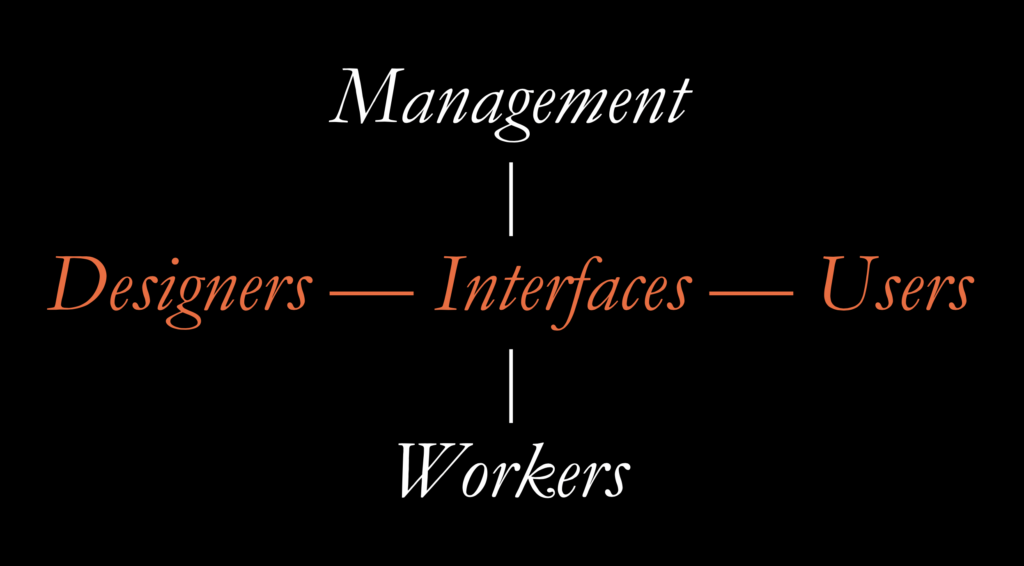

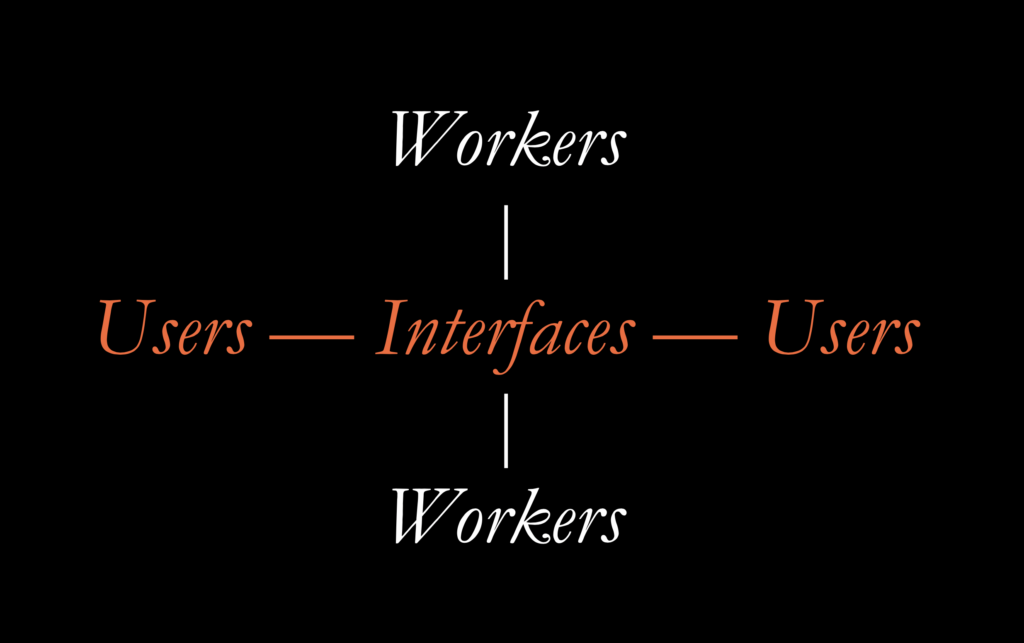

It was interesting to understand why they were supporting—why former far-right voters or naive voters, put in that way, were supporting Bolsonaro. Vieira Pinto explains it well. I cannot go into the details of that now, but you should just know that this relates directly to the discussions we were having last week. I was explaining that hetero-management has these interfaces that block or create a buffer zone between managers and workers. This allows managers to control workers, and workers, in turn, believe they need to be controlled.

Designers and users occupy ambiguous positionalities in this process. Sometimes designers identify with managers and control users just as much as they control workers. Or, designers might try to make workers feel like they are users. Another possibility is that designers identify with workers and actually help to empower users. If they do so, the structure of this diagram would change completely, and designers would essentially become users. But we’ll get to that point later on.

Iust to remind you of the terms we used last week: hetero-management nurtures naive consciousness. Why? Because naive consciousness helps to maintain unequal structures. If people are not critical, they don’t want to change things. Extending naive consciousness to design, when designers are naive, they don’t realize they are workers, just as they don’t realize they are users.

Let me give you two examples of how this impacts designers’ lives.

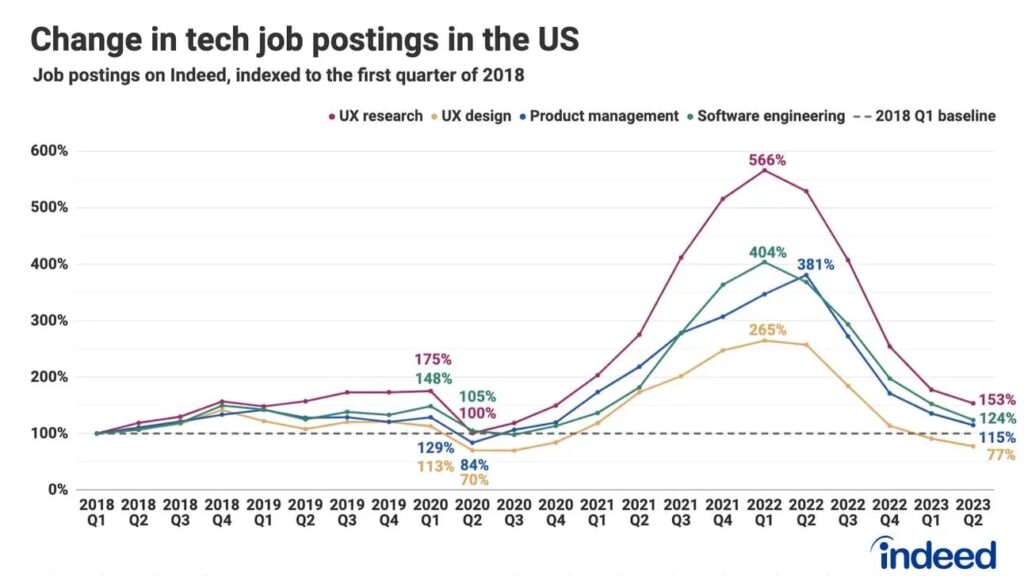

Over the past four years, particularly in the United States, designers in the tech sector experienced a boom. There were 600% more job openings in UX research and UX design, with 265% more new jobs being created. However, since 2023, the number of jobs available has declined significantly. In other words, job opportunities are being eliminated. And that’s what companies call layoffs. Essentially, people are being kicked out of their jobs because the industry doesn’t need as many UX designers. Now, 30% of UX designers are unemployed.

This is not the same for UX researchers. As you can see here, the demand for UX research is still higher than before. It’s still a growing profession. And by the way, here’s a tip: if you’re thinking about going into the industry, the MXD research program can help you transition into becoming more like a UX researcher than a UX designer. UX researchers also get better salaries. If you want to study this topic on your own, go for it. I am not going to approach this directly here because what we are doing in this program is something more substantial than UX research. What we do here is probably more interesting for the general public than just supporting capitalist companies in their exploitation processes. However, it’s worth noting that many of the techniques we use are also naively employed by UX researchers in capitalist industries.

To wrap up this point: many UX designers and UX researchers think they are not even workers. They believe they are becoming strategic; they think they are having “a seat at the table,” that they are becoming leaders. But as soon as companies don’t need them anymore, they are fired. This serves as a reminder that they are not owners—they are not capitalists.

On the other side, what’s less known and realized is the condition of being a user. For instance, if you are a user in a country outside the United States, and the U.S. ends up in a trade war with your country, your digital services or design tools could be jeopardized. This is what happened to Venezuelan designers in 2019. Many of them had files stored in the Adobe Creative Suite cloud, and they didn’t realize beforehand that this could happen. Then, all of a sudden, these services were shut down for these users, and they lost the files stored there. Designers, when they don’t think of themselves as users, don’t think about backing up their files. They don’t consider the possibility of something going wrong with their tools. They don’t even think about using free and open source software, which would always be available to them.

Instead, they believe they are part of this creative, rather privileged, class that’s going to transform the world for the better, as part of this big wave of good energy. That’s an illusion. It’s all capitalism, just fantasized—just deceiving people. We need to be clear: we are workers, and we are users. And once you start to realize that, you can design as a user—not just design for or design with users.

Designing from an authentic positionality is a great driver for design work. For example, Black designers organized themselves and produced this marvelous book, The Black Experience in Design: Identity, Expression, & Reflection. Women have also organized, producing books like Women Made: Great Women Designers. Queer people created Queer X Design, documenting 50 years of LGBTQ signs, symbols, banners, logos, and graphic art. There are also national positionalities. Brazilians, for example, are well represented by Brazilian Modern Design by Maria Cecília Loschiavo dos Santos. In a more complex positionality, Feminist Designer: On the Personal and the Political in Design book claims that even men can become feminist designers if they abide by these principles and join the social movement.

There are many other emerging identities for designing as someone from a specific group. However, these identities often overlap. You’re not just a queer person—you might also be a queer woman, queer man, queer trans, or queer non-binary person. And when you add class, race, and handiness to the mix, it becomes even harder to figure out which identity drives you in the fight against oppression.

What is handiness? I’ll get to that in a minute. Handiness is actually a particular contribution from Álvaro Vieira Pinto’s work that informs our design practice. Together with Rodrigo Gonzatto, a Brazilian researcher and collaborator, we’ve been unearthing and translating this concept from Vieira Pinto’s book. In that book, Vieira Pinto describes handiness as the relationship between what is available around your body for you to use and the historical labor involved in making it available. Nothing is gratuitous, for free, God’s gift, or natural in the human world. Someone worked to make those things available.

If your relationship with that labor is alienated—if you are unaware of the work behind it—you will have underdeveloped handiness. You won’t know how to use things because you don’t understand how they were designed or under what conditions. Considering handiness in discussions of positionality and oppositionality means designing as workers and users. Unfortunately, class is often neglected in discussions of design because we live in a capitalist society that profits from maintaining class oppression. For example, before Trump’s return to power, the U.S. had more liberal policies toward gay and trans rights. Now, these rights are under threat. But in both cases, capitalism profits—selling products and services tailored to queer people, including books like the ones I mentioned.

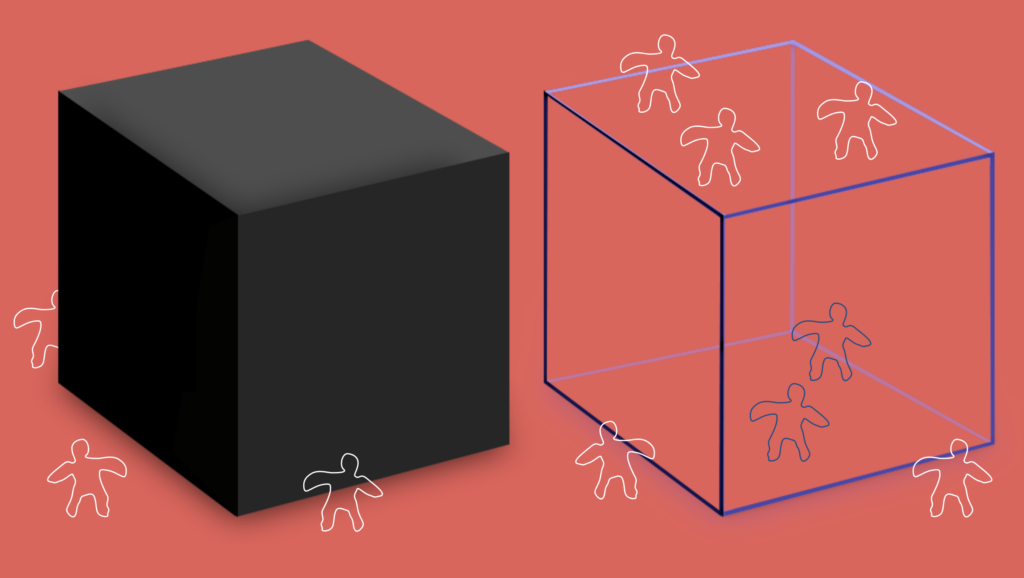

If we want to truly fight oppression, we must engage as users working with other users and as workers working with other workers. We need to design interfaces collaboratively. So, if you really want to fight oppression systems, this is the diagram. We need to engage as users working with other users and as workers working with other workers, designing interfaces collaboratively.

I already gave you this example—I’m just reminding you—but self-management is a tradition from the workers’ movement and has been explored in many different parts of the world. I’m showing Yugoslavia here because they were probably at the forefront of socialist self-management during the 1970s. We also do self-management in our design studios, as I explained last week. In that kind of studio, we practice self-conscious design, where designers design interfaces as designers by themselves, for themselves—like the Crisis Deck project. It’s about designers understanding what it means to be a designer.

But what does designing as a user—designing done by users for users—look like? That’s my question today.

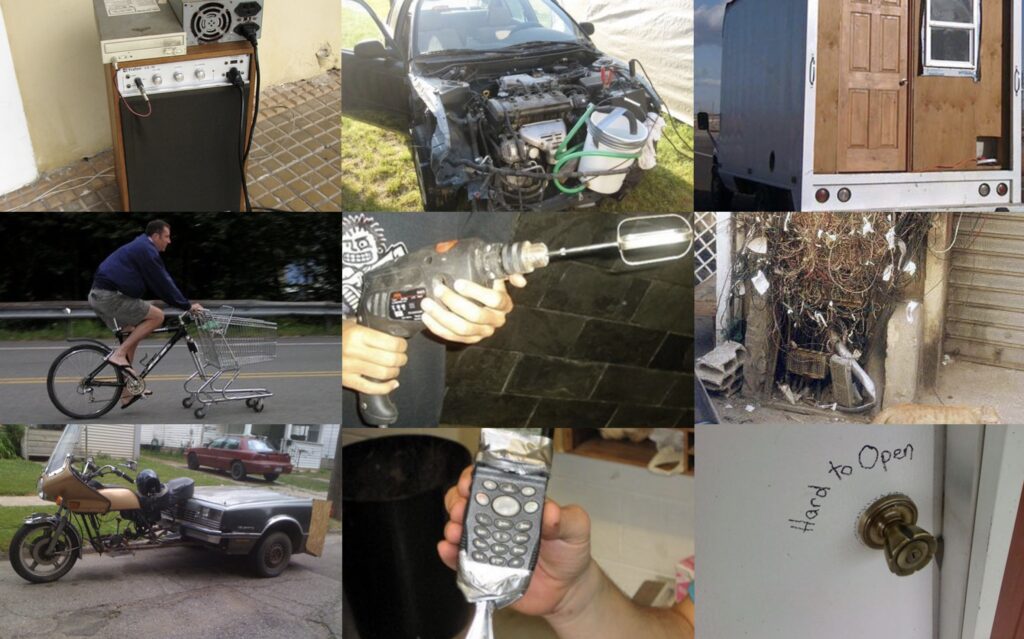

For a quick overview, here are some examples of designs made by users. At first glance, they might look quite crude. You might think, “Wow, this isn’t design. This is just a fix, or a kludge.” You might have different terms for this in your language. In Brazil, we call it gambiarra. In Colombia, they call it malicia indígena. In Mexico, it’s called rasquache. In India, it’s jugaad.

This is the best design out there, at least from my perspective. You know why? First of all, it reuses resources that have already been extracted from the environment. This is typically recycling or upcycling, meaning there’s a lower environmental impact. These materials could have ended up in a landfill, thrown into rivers, or even in the ocean, polluting the environment in so many ways and eventually coming back to us through food.

Instead, two things are saved: the material doesn’t go to the landfill, and people don’t buy new products. If people don’t purchase new produces, no new material extractions are needed. So, you save twice when you use a design like this. Another important aspect is that such designs are not protected by intellectual property rights. Anyone can copy these solutions. They typically spread—you see it, you copy it, you transform it, and maybe even improve it. It’s very open source. Even before the concept of open source and free design was invented, people were already doing this. There’s more to say about this, but I’m not focusing on these examples today.

What is the implication of recognizing these designs for modern design and its foundational definition of good design? These designs are deliberately against modern design. They are saying through other means: “We don’t care about modern design or we don’t want to look modern.” Why? Because modern design is often too expensive, inaccessible, and less authentic. It lacks a connection to local culture and fails to express local values. So, designing as a user means opposing modern design and its definition of humanity, which is something much more substantial.

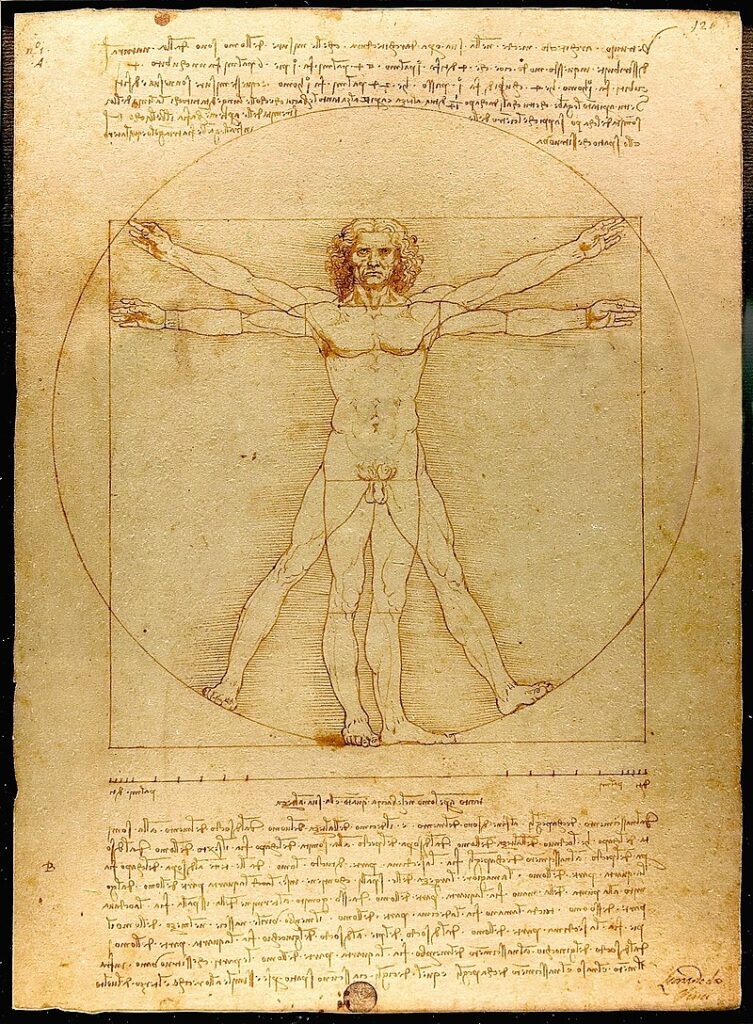

Behind every piece of modern design, there’s a specific view of humanity—a view of a white, male, able body that has been visually expressed by many artists. Perhaps the most famous example is Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man. It’s not so much about this particular image but what it represents—that the standard, the default designer, creator, and user is this white male body. The main idea behind this picture is the supposedly perfection of that body proportions, proved by fitting it inside a square and, at the same time, inside a circle. This is just the geometric meaning, but there’s definitely a more sociological meaning. What it means is that the white male body is considered the perfect body, while non-white female bodies, for instance, are seen as less perfect. If we look at all of the aforementioned positionalities, this is the one that matters, and the rest is dismissed as irrelevant.

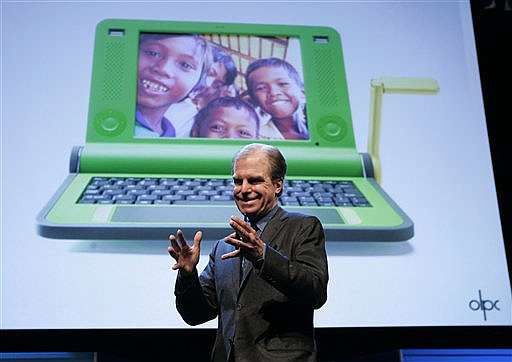

Fast forward 500 years, and you still see this overvaluation of the white male body behind modern design. Here’s Nicolas Negroponte, the director of the MIT Media Lab for a while. In this picture, he’s acting as an entrepreneur, the founder of the One Laptop Per Child startup, which aimed to bring laptops to underdeveloped countries like Brazil for $100 or even less.

As you can see, the difference between the Renaissance and modern times is that in the past, the white male body was shown alone. Now, it’s shown in contrast to people of color—non-white, Black, or brown bodies. You basically see this person saying, “Look, we are great people. We know what children need to know. But we also feel guilty for being superior, so we want to share some of our privileges by bringing cheaper laptops to these people. Please invest in our company, and we can help reduce white guilt or the white man’s burden.”

This project was unsuccessful, in part because of its racist undertones. MIT and the One Laptop Per Child project didn’t want to engage in dialogue; they just wanted to throw laptops into these communities. In fact, they literally had a plan to throw boxes of laptops into villages in Africa without any explanation—just leave the laptops and go away. This approach was also depicted by the controversial movie The Gods Must Be Crazy, where a Coke bottle is thrown from an airplane and changes life in an African village. They thought laptops would do the same, helping Africa out of what they called “a state of underdevelopment.”

Nowadays, Africa is often criticized for “not being capitalist enough.” This was even on the cover of one of the major economic magazines—The Economist. The critique forgets the real problem: centuries of colonialism. Africa is still recovering, with some countries still maintaining strong ties to their former colonial rulers.

This is part of the problem: they—the White bodies—believe they are superior and know what Black bodies should do. This burden of superiority is deeply embedded in modernist design. Designing as a user counters this narrative by shifting the designers’ positionality.

For me, this began in 2007 when I co-founded the Faber-Ludens Interaction Design Institute with like-minded colleagues. We started with a different idea of humanity. The term Faber-Ludens opposes Homo sapiens. It envisions a new kind of human who plays while making things and creates a world in an imaginative way, instead of relying solely on rational categorizations. One of our projects featured a woman sharing her creation—a robotic addition to her body that expanded her senses. I can’t recall the details, but the idea of a cybernetic body, of being a cyborg, was already part of the discussion about what it means to be human at that time.

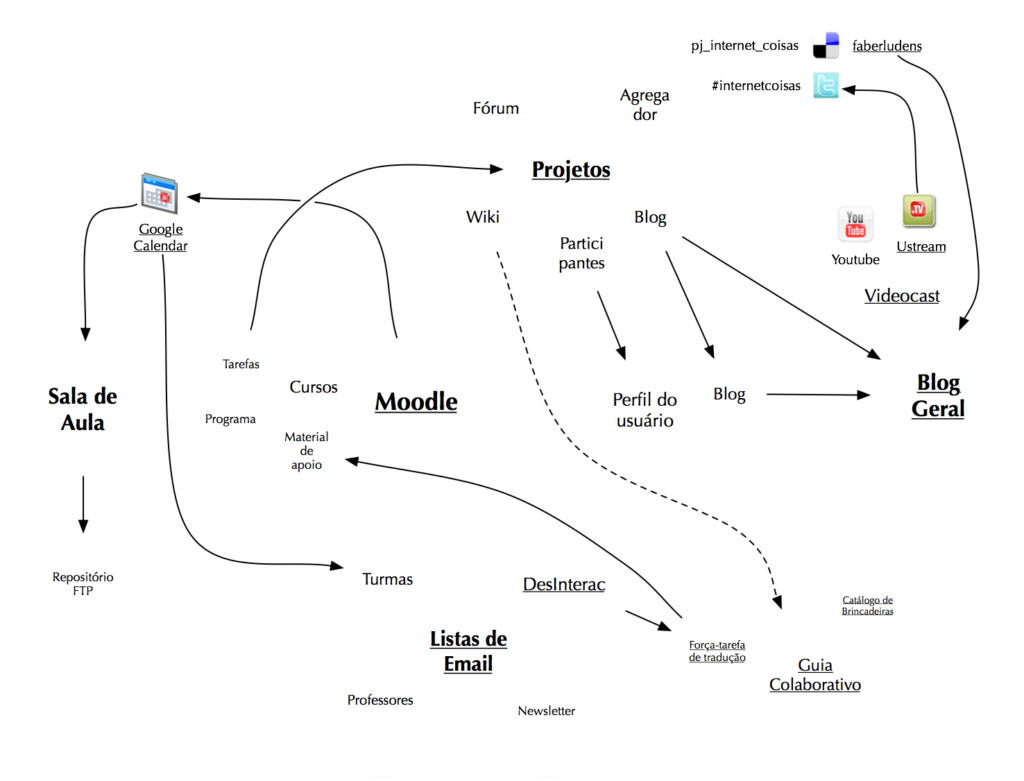

We had a website where we shared all our projects freely so everyone could see what we were designing. We believed it was important to trailblaze the field and invite more people to participate. At one point, we had so many online services connected to the website that we called it a media ecology—or a mashup. Some tools were open-source software, like Moodle, which is similar to Canvas here at the University of Florida. Moodle is open-source and widely used by universities around the world, including my previous university. We also used platforms like YouTube, Ustream, and others. Many people engaged with us through these different channels. That was the first moment we realized we couldn’t design one single thing. Instead, we had to design things in relationship with each other, as part of an ecology.

At the time, we didn’t have any programmers on staff. We had to rely on open-source software and design using visual programming languages at a basic level. That’s when we started to realize we were users—designing as users of these foundational platforms that we were combining.

Looking back and contrasting what was being discussed in the design industry at that time, we saw Apple drawing a lot of attention. Everyone said Apple had the best design, but Apple had the most secretive design process. Nobody knew how they designed their products. They had this beautiful black box that hid everything about their design methods.

We didn’t want to follow that path. We also didn’t want to do what, in the opposite direction, was done under the label of design thinking. This approach, promoted by Stanford’s d.school, was partially based on the methods developed over many years by IDEO. That company has a major office close to Stanford, so they work closely together. They started developing various materials to share their design process, positioning themselves in opposition to what Apple was doing. They wanted to share their design methods. However, they still had strong commercial interests and, in some cases, adopted an even more explicit colonialist approach than Apple.

For example, many of IDEO’s open initiatives and the Human-Centered Design Toolkit materials were targeted at underdeveloped or third-world countries at the time. We observed this from Brazil and thought, “We don’t want to do that. But we still want to do something similar.” We wanted to draw ideas from Apple and IDEO, but create something more reasonable and sensitive to Brazil’s context.

At the same time, we were watching the rise of the Open Design concept, especially in Europe and later in the United States, with initiatives like fab labs—places where people could build anything, share source code, and see others further develop their projects. What we did at Faber-Ludens was eat open design through anthropophagy, a cultural appropriation strategy pioneered by indigenous people in Brazil. This idea was later developed by artists during Brazil’s modernist movement in the early 20th century and expanded during the Tropicália movement under the military dictatorship.

Closer to our time, in the 2000s, the digital culture movement led by Gilberto Gil—a famous Brazilian musician, politician, and pioneer in using Creative Commons for the arts—helped shape this approach. We drew from all these sources to develop Design Livre, our design approach. In Design Livre, we emphasized transparency. We used “transparent boxes” that you could look into and meet other people because the project was a collaborative, open-source effort with participatory channels. Anyone could join.

Once we established the ideology behind Design Livre, we wanted a platform to support it. We tried to integrate everything we were doing on different platforms at Faber-Ludens (remember the media ecology I mentioned?) into one unified system. This became the Corais Platform, which we created in 2011 as an alter/native to OpenIDEO.

Whenever you come to me excited talking about design thinking or the double-diamond model, remember that since at least 2011, I’ve been looking for anticolonial alter/natives to these design approaches. If you bring them to me, the first thing I’ll do is help you see its underlying biases.

Returning to the Corais platform: we developed it using Drupal 6.0 and more than 200 different open-source software tools, mashed together. We had a radical transparency policy—all project content was, and still is, accessible online without a login. You can check out projects there from over 10 years ago, as everything is mandatorily shared under Creative Commons licenses.

Here’s what one project looks like. For example, this is a card deck we were brainstorming. We were collaborating on the text that would be included in the deck. Each collaborative tool was an open-source software integrated into the platform. I designed and developed all of this using visual programming or high-level programming. I didn’t know how to program very well, but I still managed to create this complex platform. And you can do it too—it’s not as difficult as it seems, thanks to the generous open-source programmer community that shares their work freely. At one point, we were even surpassing Google Drive. Imagine that—we were better than Google Drive! Of course, we couldn’t sustain that for many years, but for a time, we outperformed them.

Beyond the Faber-Ludens website, Corais also connected to physical spaces. We envisioned Corais as a platform that would link fab labs and studios. It also featured our signature method cards, which became known as UX cards. After designing these cards on the platform, we tested them in organizations we collaborated with and later integrated them back into the platform.

Corais allowed us to create virtual cards that you could use just as you would with physical cards on a table. We even used the platform to collaboratively write a book about the Design Livre ideology. The writing took place over an entire week, using tools like Google Drive, which at the time wasn’t fast enough for what we needed. We also used virtual conferencing—these technologies were experimental back in 2012. Designing in a hybrid mode like this was pioneering.

The result was the book Design Livre. It was translated into Spanish, though not yet available in English. As we continued using the Corais platform, we shifted from designing it for others to designing it for ourselves. By 2014, we concluded that the open innovation strategy of Faber-Ludens didn’t work for many reasons. The dispute between capitalist and socialist ideologies within Faber-Ludens caused its closure. Essentially, the capitalists and socialists, who had worked democratically in the past, could no longer agree. But Corais outlived Faber-Ludens.

A lot of collaborative culture producers—people associated with the Brazilian digital culture movement sparked by Gilberto Gil in the early 2000s—were really excited about using Corais for their purposes. They wanted to organize popular or folk culture initiatives using digital technologies and explore the possibilities of free software. They wanted a national platform rooted in Brazilian culture, where they could contact the developers and keep capital within the country. They wanted self-management interfaces to enable self-management, and they wanted everything to be under Creative Commons with extensive data transparency.

Here’s one of the first digital culture movement projects: Movimento Conchativa. They managed a large concert hall owned by a university that wasn’t using it. The space was handed over to cultural producers and activists, who started organizing events, offering courses, and revitalizing the surrounding community. In 2012, after installing a chat feature on the platform, I connected with one of the most active entrepreneurs in that group, Pedro Jatobá. Pedro was part of several self-managed collectives that wanted to experiment with digitally mediated solidarity economies in cultural production.

They wanted to print and design their own money but didn’t know how to do it using digital technologies. They were inspired by Brazil’s workers’ movement, which had used solidarity economies for decades. It’s worth mentioning the Landless Workers’ Movement as one of the biggest promoters of solidarity economies in Brazil. They facilitate bartering among food producers and even print local currencies.

Jatobá proposed creating a digital social currency module as part of its metadesign project. Corais hosted many projects, but it also had a space for metadesign—projects that improved the platform itself. This was not just a buzzword for us; it was integral to how we worked. We developed the digital social currency module using open-source software. Here’s the result: at any time, you could see the health of the community currency. Each participant’s balance was visible, with most showing green, meaning they contributed more than they took. If there were many negative balances, it indicated the community was in debt—a sign that people were taking resources without giving back. It was a fascinating indicator of community health.

In physical spaces, the same dynamics played out. For instance, at a theater school that had faced budget cuts, participants used the system to keep things running. They fixed broken doors, maintained the space, and ensured courses continued.

Here’s how the system worked:

- Someone posted a need or task, like fixing a door.

- Another person fixed it and posted, “I fixed it.”

- A third person checked the work and confirmed it was done.

- A fourth person operated the “bank” and transferred funds from the community’s common resources (or “commonwealth”) to the person who completed the task.

The person who received the funds was required to spend the money within the community, often on courses offered by the school. To participate in the school, you had to pay by completing services for the school, earning money to pay back the school.

The cycle ensures accountability and recognition. If you simply ask people to volunteer without recording their efforts, they may not feel appreciated. What we discovered was key to the sustainability of this effort, which lasted three years: people felt recognized by the system, often more than if they were paid in regular money.

The system involved at least two people acknowledging the work, and it was all public. Others could see the transactions, reinforcing the radical transparency philosophy. At that time, in Brazil, there was this very cool initiative called the Hacker Bus. A group of hacker activists traveled around Brazil in this bus, conducting workshops on data transparency, hacking governmental accounts to extract public information, and publishing it to expose corruption. These activists eventually ended up working for the government to help implement policies that made transparency measures regular and systematic. Brazil has been doing a lot of work to shed its reputation as a corrupt country. Many politicians have been caught by these transparency measures—including Bolsonaro, who was caught in one of these systems as public scrutiny became more accessible.

We wanted to make this not just a governmental initiative but part of the culture. If everyone is accustomed to being held accountable to the public—not just the government or certain individuals—the whole culture would embrace transparency. On the other hand, corruption often stems from the feeling that your work is not adequately recognized or valued, which leads people to steal as a way to profit. If people were recognized for their work and had good career prospects, why would they resort to corruption?

There are cities in Brazil already experimenting with solidarity economies on a large scale, involving thousands of people. These experiments include providing a basic minimum income through local currencies and significantly reducing poverty. This is meant to increase the public’s trust in itself as a collective of citizens who can produce useful things to society just by being there.

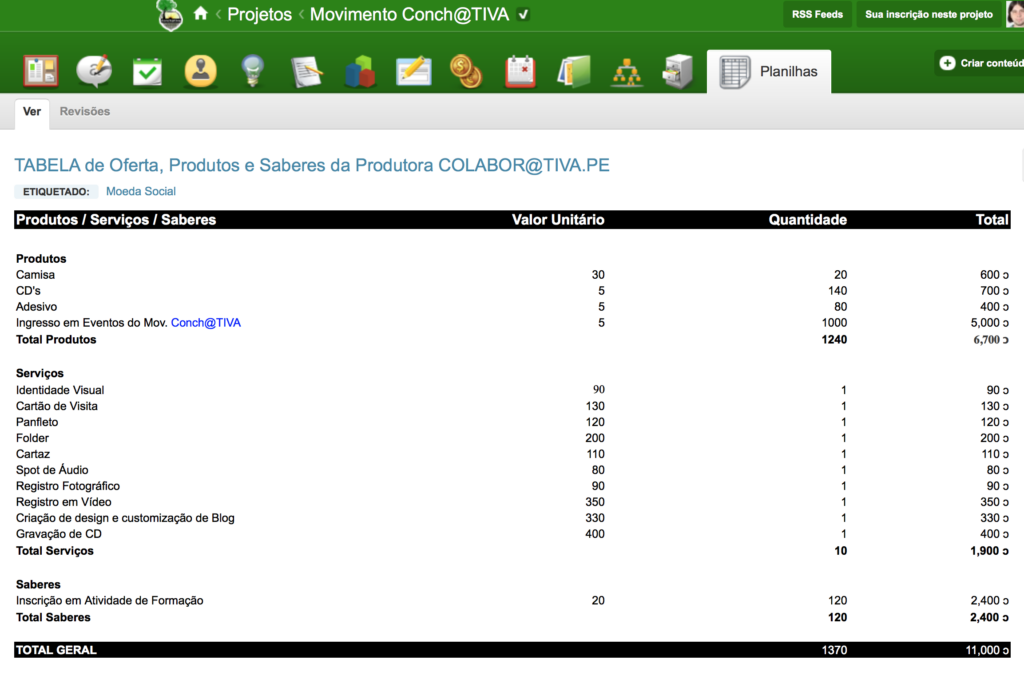

In our case, the backing for the currency—the trust in it—was based on the collective capacity of the group to produce certain services each month. For example, everyone in that particular collective could commit to producing one visual identity project, one business card, one folder, and one poster per month. These services would cost a certain amount in their community currency for anyone who wanted to buy them.

The collaborative cultural producers knew for sure that they would be able to produce because if someone had the money and ordered a service, and the service wasn’t delivered, the trust in that currency would go down. That’s how they built a solid economy—by promising to produce a certain amount of goods and services within a specific period of time.

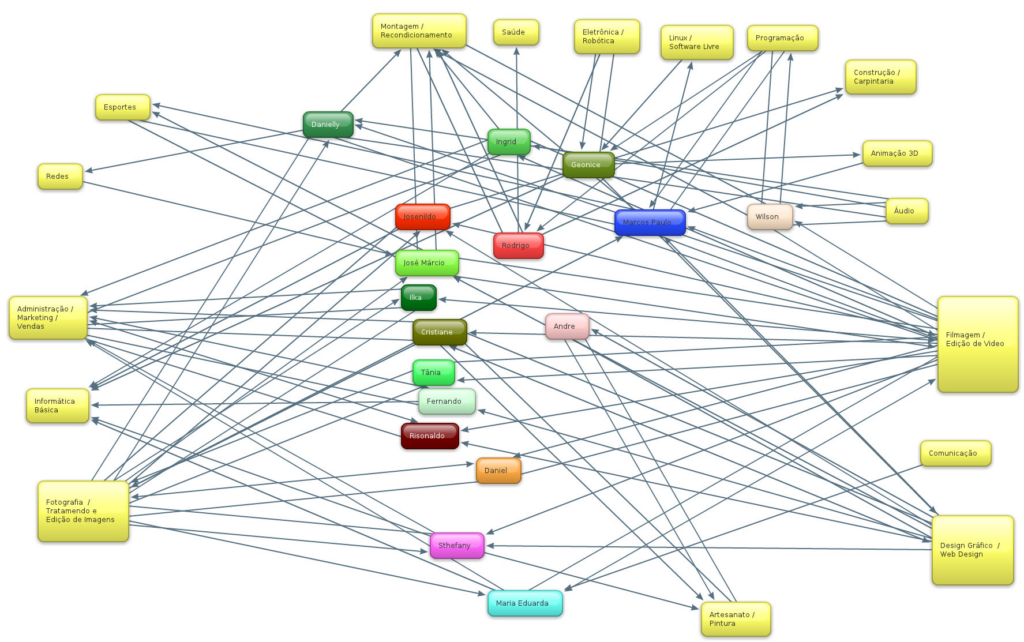

How do you come up with those numbers and services? They had a very detailed method for mapping the wide range of skills and expertise shared within the community. For example, in this particular group, many people knew how to produce audiovisual materials like recording, editing, and video production. That’s why they could produce a lot of movies. There were fewer people skilled in network management, but they could still produce those services if needed.

Pedro Jatobá engaged in a two-year Master of Science research project, during which he documented everything he learned using the Corais platform. All of this is explained in detail in his master’s dissertation, currently available only in Portuguese. We also wrote a more accessible, popular book called Coralizando—not just Pedro Jatobá but me and many others who were using Corais at the time. We wrote it as a manifesto to share what we had learned. That was in 2014. Now, 10 years later, Corais has hosted 700 projects with 7,000 members spread across Brazil.

The platform is less active now because the technology is outdated. However, a new platform emerged from this one: Rios. This one was designed by EITA, a cooperative for IT development that originated in the Landless Workers’ Movement but later became independent. They created this tool to help social movements better organize and share information. It’s similar to Corais but has a more modern look, designed to align with current ways of interacting through apps and mobile devices.

One of my former students worked with EITA, designing Rios’ metadesign channel. She was deeply interested in social movements and studied how collaborative culture producers appropriated Corais. She’s also the author of the second article you read this week. Isabella Siqueira did this for her final project while writing her paper on Service Design by the Oppressed.

What we are now realizing is that we are indeed designing as users with other users or as workers with other workers. We are designing interfaces that enable us to self-manage. Designing interfaces as users means being more attentive to past, present, and future handiness—this relationship between what is available and the work involved in making it available.

By joining workers in their process of liberation—such as learning how to overcome capitalist exploitation through solidarity economies—we also liberated ourselves. We freed ourselves from capitalist, colonialist, and patriarchal modes of design thinking, like those promoted in the underdeveloped world by IDEO, the Stanford d.school, OLPC, and many other initiatives that suppressed solidarity and alternative ways of living that are cultivated by social movements.

Essentially, we were working against huge powers, and yet we thrived for so many years. I can’t say the current situation is entirely hopeful for the projects I showed you, but there are definitely other projects being developed by people who participated in Corais, Rios, or Faber-Ludens. And you’re part of this too. The MXD studio is a place where these ideas and practices are brought forward. You can build on top of them and liberate yourself through this process. Don’t be shy to design like a user.

References

Noel, L. A. (2023). Design Social Change: Take Action, Work Toward Equity, and Challenge the Status Quo. Ten Speed Press.

Boal, A. (2005). Games for actors and non-actors. Routledge.

Pinto, Á. V. (2020). Consciência e realidade nacional. Volume II: A Consciência Ingênua. Editora Contraponto.

JATOBÁ, Pedro Henrique Gomes. Desenvolvimento de ambientes virtuais de aprendizagem e gestão colaborativa: casos de cultura solidária na economia criativa. 2014. http://repositorio.ufba.br/ri/handle/ri/21715

GONZATTO, R.F., VAN AMSTEL, F.,and JATOBÁ, P.H.(2021) Redesigning money as a tool for self-management in cultural production, in Leitão, R.M., Men, I., Noel, L-A., Lima, J., Meninato, T. (eds.), Pivot 2021: Dismantling/Reassembling, 22-23 July, Toronto, Canada. https://doi.org/10.21606/pluriversal.2021.0003